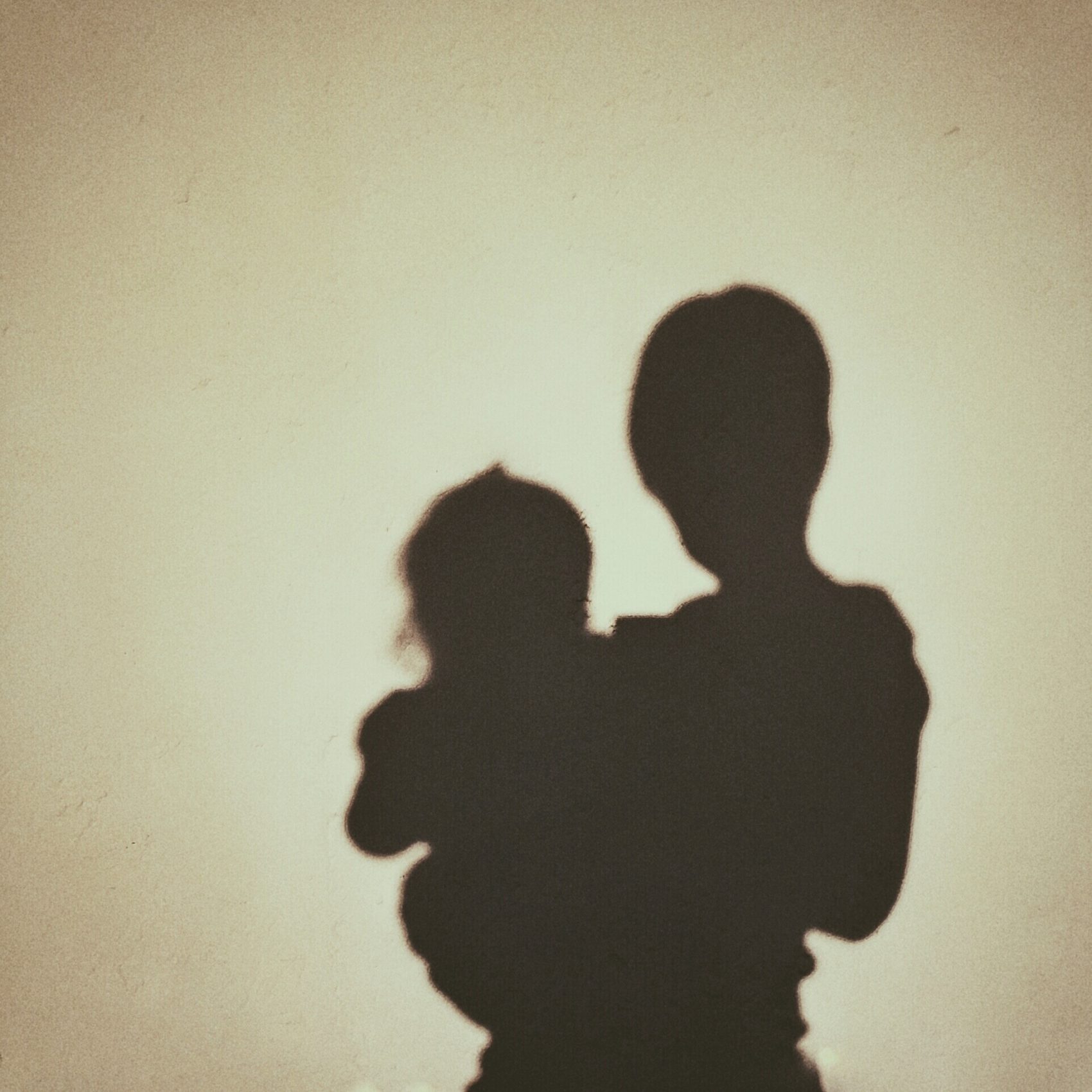

How Child Services Punishes Mothers With Substance Use Disorder—And Their Children

Rather than separating families, child ‘welfare’ agencies should help families get access to the care they need.

Megan Webbley was a 31-year-old mother of four when she died of a drug overdose on Sept. 29. It was a Sunday. It was still warm outside, but the breeze was crisp and the trees were already beginning to sport an autumn blush. She was in New Hampshire, attending treatment for opioid addiction. It had been an ongoing battle for 14 years, but her family had hope. They did not expect to lose her that day, and still don’t know exactly what happened, or why she relapsed.

I did not know Megan, but when I read her online obituary, it’s impossible to ignore the similarities between us. We were both born in 1988. Both of us were mothers. Both of us enjoyed music and makeup, as her father wrote in the obituary. Both of us felt called to advocate for “the underdog.” And we both shared that same, stigmatized diagnosis: opioid use disorder.

Then, of course, there is that other similarity we shared. We both became involved with child protective services. “I am hoping that the Department for Children and Families rethinks its mission to be the punisher of addicted mothers, the separator of families and the arbiter of children’s futures,” editorializes Megan’s father after a short, loving description of her life in Vermont. “Because, as one would guess, once the mother is separated from her children, desperation sets in, even with the brightest and most determined of mothers.”

Child services agencies investigated allegations involving 3.5 million children and their families in fiscal year 2017, the most recent statistics available. Of those, an estimated 674,000 cases were substantiated, the vast majority of which involved neglect, which is often coded language for poverty. That means the majority of child services cases could potentially have been addressed with better access to social services, like housing or job assistance, child care, food resources, and healthcare.

But when drug use is involved, that often becomes the focus of the case. Parents are ordered to complete questionable treatment programs and comply with invasive, sometimes embarrassing, surveillance tactics like random observed urine drug testing. Again and again, stories surface in which parents recount having to quit their jobs to attend daily treatment groups, or to comply with drug testing referrals. By some estimates, as many as two-thirds of all substantiated cases involve parental substance use, and it’s cited as a factor in roughly 36 percent of cases involving a child’s removal from the home.

I became involved with the Broward County, Florida, child welfare system in April 2018, after a dispute with my in-laws sparked an investigation. That investigation was brief, and I was not called or notified until there was already a petition filed to remove my daughters. My history of engaging in methadone and buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder were repeatedly referenced and scrutinized by the state attorney prosecuting my case. Even when my hair and urine drug tests came back negative, the Department of Children and Families did not drop its case.

Although the investigator acknowledged that my daughters showed no signs of abuse or neglect, I was ultimately charged with neglect and posing an imminent risk of serious harm. My in-laws were granted physical custody of my daughters, then 2 and 4, while I was ordered out of their home and guaranteed only one supervised visit each week. I was mandated to maintain stable housing and income, undergo a psychological evaluation, engage in trauma-informed individual counseling and substance use treatment, take parenting classes, and submit to random drug tests.

To describe what I feel every day as ‘desperation’ is an understatement.

At no point did anyone question why strict compliance with these particular tasks would ensure safe parenting. And the system seems designed for failure: Recently, when I was dropped from treatment for missing a few days due to the flu, my case was officially moved by my judge from a reunification track to an adoption track. And all this time, I have been separated from my beautiful little girls, who were always my biggest motivators for recovery. Now, we are facing permanent separation from each other. To describe what I feel every day as “desperation” is an understatement.

When an agency removes a child from her parents, it is required by law to make “reasonable efforts” to support the resolution of the issue that led to the removal. That means that child services should pave the way for parents like Megan and me to have ample access to evidence-based treatment for substance use disorder. Some agencies claim to do exactly that, and maybe they do. But there are as many child services agencies in this country as there are jurisdictions, each functioning under guidelines detailed at the state level. Data is self-reported and nonspecific, making it nearly impossible to quantify how many parents actually receive timely referrals to appropriate treatment options.

“What happens with many of these cases … the baby is taken away and the cases move so slowly that the baby is a year old before the baby is given back to the mother,” said Loretta Finnegan, a neonatologist and researcher who has worked in addiction medicine for over 40 years and frequently testifies on behalf of parents in New Jersey whose children were removed at birth. “That’s the wrong thing to do, because if you’re talking about maternal infant attachment, you’ve destroyed the attachment by taking the baby away.” In older children, prolonged separation from a parent can cause them to experience toxic stress. It is correlated with lowered IQ, has been linked to hypertension and diabetes later in life, and can result in long-term PTSD-like symptoms.

In my case, Mishka Terplan, an obstetrician and addiction medicine physician, was retained by my attorney to consult on the level of addiction care I received, and the expediency with which I received it. He asserted in an affidavit that the treatment option I had been given—which involved a referral to detox despite my not having a physical dependency—was not evidence based, and that the six months I had to wait between the start of my case and the time I received the referral was “well beyond the standard of care.”

Recovery is finding community connection, purpose, and meaning. Motherhood fits right into that.

Mishka Terplan obstetrician and addiction medicine physician

Lipi Roy, an internal medicine physician and public health advocate, notes that “stigma still remains the major barrier to care.” When it comes to opioid use disorder, an abundance of research shows that methadone and buprenorphine, medications used to decrease cravings and withdrawal, are the most effective at preventing harm, relapse, and death. Nonetheless, judges in courtrooms around the country are barring the use of these medicines, or allow them only as short-term detoxification aids, based solely upon a misinformed idea that they represent continued drug use. Instead, abstinence-based programs that rely on 12-step peer support groups continue to be the treatment norm, despite a lack of evidence that they work—and some speculation that they cause harm.

“I don’t know of any other phenomena in medicine where the disease is stigmatized, people with the disease are stigmatized, and medicine used to treat the disease is stigmatized,” explained Roy.

In an interview, Terplan pointed out that this leaves parents with substance use histories in an impossible bind. “Recovery is finding community connection, purpose, and meaning,” he said. “Motherhood fits right into that, and yet we have this system that has labeled certain people and populations as being less deserving of that than others, so we are going to even take that away from them, or make it yet another battle in a grossly unfair universe.”

Elizabeth Brico is a freelance writer whose work often focuses on drug policy reform and the child welfare system.