His Attorneys Say He’s Intellectually Disabled. A ‘Reform’ Prosecutor Wants The Death Penalty

State Attorney Melissa Nelson is pushing for a death sentence even as more prosecutors reject capital punishment.

On the morning of May 30, 2012, in Jacksonville, Florida, Dennis Glover heard a scream come from the trailer of his neighbor, Sandra Allen, according to a statement he later gave police. He went to check on her and when he looked in, he saw blood, left, and told his girlfriend to call 911. The police arrived and found Allen had been stabbed multiple times.

The next day, the police brought Glover to the police station and accused him of killing Allen. Glover denied committing the crime and asked for an attorney, but the police continued to question him, according to a transcript of the interrogation. He told police he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and hadn’t yet taken his medication.

“Okay are you seeing … are you seeing green … men flying around here or anything?” asked one of the detectives. Glover replied he did not.

About six weeks later, Glover was arrested. He was convicted in Duval County Circuit Court and in 2013, the jury recommended a death sentence in a 10-2 vote. But in 2017, the Florida Supreme Court overturned his sentence, finding that a jury must unanimously recommend a death sentence, and sent it back to the lower court for resentencing.

But State Attorney Melissa Nelson has opted to seek death again. Nelson ran as a reform-minded prosecutor in 2016, and defeated the notoriously punitive incumbent. But in Glover’s case, Nelson seems to be taking a position that’s more in line with her predecessor than her public pronouncements to seek the death penalty judiciously.

Nelson’s decision runs counter to a growing trend away from the death penalty, a movement supported by numerous chief prosecutors. For Nelson to pursue death in a case like Glover’s is particularly egregious, his attorneys say, because of several mitigating factors, including severe mental illness and intellectual disability.

In letters to community members, Nelson seems to suggest that she would consider dropping the death penalty if not for Glover’s innocence claim and his plans to appeal his conviction.

Deacon Lowell “Corky” Hecht, a prison ministry director who visited Glover on death row, wrote to Nelson in July asking that she not pursue a death sentence for Glover. In response, Nelson wrote that her office is “open to consider any offer by Mr. Glover to resolve this matter in a manner that will provide Ms. Allen’s family the closure and finality they deserve.” However, she continued, Glover “seeks to ensure his ability to continue to litigate the merits of his underlying conviction.”

In another letter to a community member she wrote: “Mr. Glover currently maintains his innocence and remains unwilling to accept responsibility for his murder of Sandra Allen. Mr. Glover has expressed through counsel, his intention to challenge his first-degree murder conviction through continued postconviction litigation. … Under these circumstances, Mr. Glover’s current position is completely at odds with, and in fact, forecloses our ability to engage in any meaningful dialogue regarding his death sentence.”

Nelson’s office did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment on the letters.

In several wrongful conviction cases, innocent people have pleaded guilty to avoid the death penalty.

In 2007, Amy Wilkerson was facing capital murder charges for shaking to death a baby in her care. Her attorney told her if she didn’t plead guilty, she would be executed. The next day, Wilkerson pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life. She maintains her innocence and is currently represented by the Mississippi Innocence Project, the Wisconsin Innocence Project, and a private attorney.

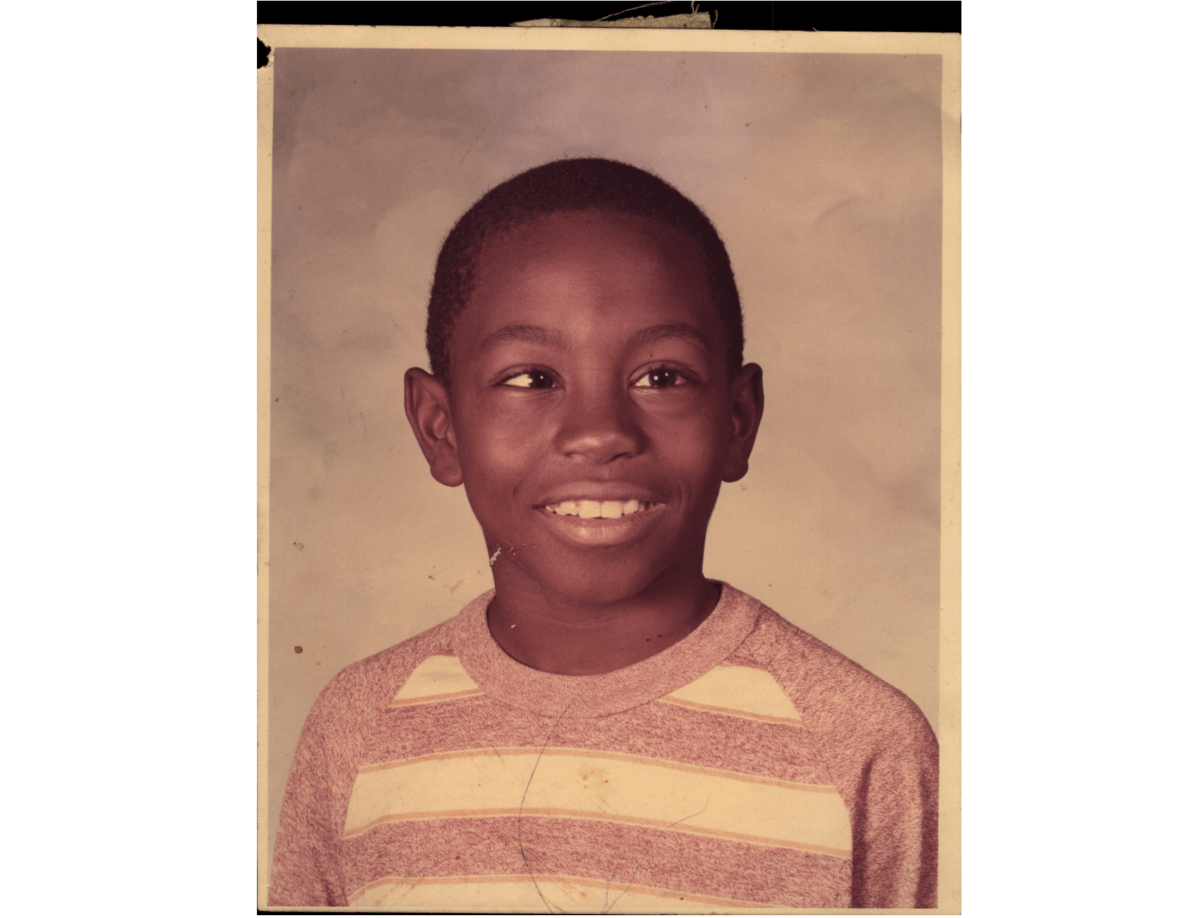

Nelson’s decision to seek a death sentence is particularly unjust, his attorneys say, because he is intellectually disabled, making him ineligible for the death penalty. As a child, Glover was placed in special education classes and left school before graduating. His scores on reliable IQ tests—administered when he was 11, and again at 49 by two defense experts—ranged from 67 to 72.

In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that it was unconstitutional to execute people with intellectual disabilities. In 2014, the Court struck down Florida’s method of determining intellectual disability in favor of a more holistic analysis. Previously in the state, only those who had an IQ of 70 or below could be considered intellectually disabled.

“This rigid rule, the Court now holds, creates an unacceptable risk that persons with intellectual disability will be executed, and thus is unconstitutional,” reads the majority opinion, which still gave lower courts plenty of discretion to define intellectual disability.

David Chapman, Nelson’s spokesperson, told The Appeal that the state’s expert disagrees that Glover has an intellectual disability. In Glover’s case, they “carefully considered both the aggravation and mitigation prior to reaching the decision to continue to seek a death sentence,” Chapman wrote in an email to The Appeal.

“The death penalty is the law of Florida and intended for the worst of the worst defendants who are found guilty of first-degree murder,” he wrote. “In 2017, this office created a panel of our most experienced attorneys to ensure a thorough review of the facts and the law of each case before a final decision is made by the state attorney.”

In a five-page report from 2015, the state’s expert concluded that Glover did not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of intellectual disability. The expert wrote that he did not interview Glover, who was incarcerated at the time and refused to speak with him. His conclusion was primarily based on Glover’s IQ score of 80 taken when he was 16 years old—32 years before Allen’s death. But the test he was administered, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, was outdated, even at the time, and not designed for children his age, according to Glover’s court filings.

Glover grew up in poverty in Georgia, and both parents struggled with mental illness, according to his court filings. As an adult, Glover was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, and schizophrenia.

In 2007, at age 43, he was hospitalized after he woke up on the side of a highway, according to his medical records. He said he was hearing voices and had tried to die by suicide, but he didn’t remember how. The day before, he had reported to an outpatient program that he had stopped his medication because, he said, “I have no money to get it.”

There are many unanswered questions about Allen’s murder, according to Glover’s attorneys with the American Civil Liberties Union—questions that a prosecutor’s office, sworn to seek justice, should attempt to answer, they said. A murder weapon was never identified and a search of Glover’s home didn’t turn up any bloody clothing.

The state’s case primarily rested on DNA evidence. Allen’s blood was found on the tops of Glover’s sandals. The police had photographed and returned Glover’s shoes to him on the day the victim’s body was discovered, but did not collect them until the end of his interrogation the next day. He could not be excluded from swabs of touch DNA taken from the victim’s head and neck, and left hand, according to the state’s DNA expert.

But much remains unknown. The state’s expert testified at Glover’s trial that DNA from at least three people found on the victim’s right hand “was too low level and too complex” to be able to include or exclude anyone. And a trace amount of semen found on Allen’s genitals was too small a sample to develop a DNA profile from, according to the state’s expert.

Glover’s attorneys have filed a motion to test, among other items, Allen’s clothing and hairs found on her body. These samples could be particularly probative because when Allen was found, her shorts and underwear were pulled down. More advanced testing, they argue, could also potentially identify who deposited the semen. A hearing on the motion, which the state is opposing, is scheduled for today.

Nelson’s decision to seek death is out of step with current sentencing practices in Florida and across the country. Twenty-two states have abolished capital punishment and an additional 12 have not carried out an execution in at least a decade, according to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC).

Across all of Florida, a state that has historically embraced the death penalty, seven people were sentenced to death each year between 2018 and 2020, far less than the often double digits of people sentenced each year in the decades prior, according to DPIC. Since Nelson took office, two people from her jurisdiction, the Fourth Judicial Circuit, have been sentenced to death.

The growing movement to abolish capital punishment is supported by numerous chief prosecutors. This month, a dozen chief prosecutors in Virginia sent a letter to legislative leaders calling on them to ban the death penalty. Newly elected Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón issued a directive stating his office will never seek a death sentence.

“The electorate and the prosecutors that they’re electing [are] moving away from our nation’s past pervasive use of the death penalty,” said Miriam Krinsky, executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution. (Fair and Just Prosecution is a fiscally sponsored project of The Tides Center. The Tides Center is also a fiscal sponsor of The Appeal.)

Cases like Glover’s were common under Nelson’s predecessor, Angela Corey, who was state attorney from 2009 to 2017. As of August 2016, Corey’s office had sought and secured death sentences for 24 people, according to the New York Times magazine. Corey sought a death sentence for Thomas Brown, who had an IQ of 67 and had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, according to a report by the Fair Punishment Project.

Voters elected Nelson in hopes she could begin to correct these types of injustices.

“We’re trying to bring broader thinking about what public health and public safety look like,” Nelson told the ABA Journal in 2019. Nelson was featured in the journal’s cover story “Change Agents: A new wave of reform prosecutors upends the status quo.”

In 2018, Nelson launched the state’s first conviction integrity unit to review potential wrongful convictions. “We did this because one of the things I ran on was restoring trust in the work that we do,” Nelson told the ABA Journal. “If nothing else, we’re willing to take a look at our mistakes to ensure they don’t happen again.”