How Fines and Fees Criminalize Poverty: Explained

In Georgia, a man stole a can of beer worth $2 from a corner store. The court ordered him to wear an ankle monitor for a year. The company administering it, Sentinel Offender Services, charged him so much money that he eventually owed more than $1,000. Trying to keep up with his payments, he sold plasma, but he fell behind and the judge jailed him for non-payment.

In our Explainer series, Justice Collaborative lawyers and other legal experts help unpack some of the most complicated issues in the criminal justice system. We break down the problems behind the headlines—like bail, civil asset forfeiture, or the Brady doctrine—so that everyone can understand them. Wherever possible, we try to utilize the stories of those affected by the criminal justice system to show how these laws and principles should work, and how they often fail. We will update our Explainers quarterly to keep them current.

In Georgia, a man stole a can of beer worth $2 from a corner store. The court ordered him to wear an ankle monitor for a year. The company administering it, Sentinel Offender Services, charged him so much money that he eventually owed more than $1,000. Trying to keep up with his payments, he sold plasma, but he fell behind and the judge jailed him for non-payment.

In Amarillo, Texas, Janet Blair-Cato received a “barking ticket” because the abandoned dogs she rescued made too much noise. Police also gave her tickets for failing to obtain the proper vaccinations and buy dog tags. In total, she owed thousands of dollars. She missed an installment on her payment plan, and the judge issued a warrant for her arrest. She spent 52 days in jail. Two days after her release, she received a new barking ticket. She has stopped rescuing dogs.

In Macomb County, Michigan, the sheriff’s department arrested 32-year-old David Stojcevski because he did not pay a $772 traffic ticket for careless driving. He was ordered to spend 30 days in jail, but he died on the 17th day after experiencing seizures and convulsions due to drug withdrawal.

To raise revenue and make up for budget shortfalls, cities, states, courts, and prosecutors levy hefty fines at nearly every stage of the criminal justice system. People leaving prison owe on average $13,607 in fines and fees. For those who are poor, these fees can be catastrophic. An inability to pay can lead to a suspended license, additional fees, and even jail. In this Explainer, we explore all the ways the poor are regressively taxed in the justice system, and what can be done to stop these practices.

1. People receive crushing fines and fees throughout the criminal justice system.

Whether it’s a city imposing the fees or a court system, the effect is the same: an added burden on those who can least afford it.

Cities assess fees for minor infractions.

To increase revenue, many states and municipalities impose hefty fines on those charged with minor offenses like traffic violations, jaywalking, or even leaving a trashcan on the street. Because the offenses are “minor” and because the penalties are, at least superficially, not severe, people often receive these fines without a lawyer to help contest them. [Kendall Taggart and Alex Campbell / Buzzfeed]

Ferguson, Missouri, is probably the city best known for abusing this practice. Rather than raise taxes, the city, home to the Fortune 500 company Emerson Electric, charges hefty fines and fees for offenses as minor as “walking in the roadway,” walking with “saggy pants,” or putting out the trash on the wrong day. Police officers’ evaluations were tied to their ticket-pushing “productivity,” and, in 2013, fees raised through municipal court fines amounted to 20 percent of the city’s budget. [Walter Johnson / The Atlantic]

Qiana Williams, a homeless single mom, was one of many ensnared in Ferguson’s fee trap. At 19, she received a ticket for driving without a license. She missed a court date and the police arrested her. Unable to pay the $250 bond, she stayed in jail. That began her cycle through the system where, in total, she spent over four months in jail because of unpaid tickets and fines. On one occasion, police arrested her after she called them because her ex-boyfriend assaulted her. [Whitney Benns and Blake Strode / The Atlantic]

This is a national problem. In Austin, Texas, Valerie Gonzalez lacked a driver’s license but needed to drive her five kids to school and her husband and herself to work. Over the years, she amassed more than $4,500 in fines for driving without a license. She could never pay them because she was so poor that she often lived out of her car. When police arrested her on traffic warrants, a judge ordered her to pay $1,000 that day or spend 45 days in jail. [Jazmine Ulloa / Austin American-Statesman]

Courts impose fees for arrests, lawyers—and virtually everything else.

Courts impose astronomical fees on those charged with crimes, fees known as legal financial obligations. These include arrest fees, bench warrant fees, lawyer fees, crime lab fees, jury fees, and victim assessments. There are even fees for sleeping in jail. In 1991, just 25 percent of convicted people received court-ordered fines. In 2004, 66 percent did. [Alana Semuels / The Atlantic]

According to a study conducted by National Public Radio, in at least 43 states, defendants must pay a fee for a public defender. In at least 41 states, they are charged “room and board” for prison stays. And, in every place but Washington, D.C., they must pay to wear an electronic home monitoring device. [Joseph Shapiro / NPR]

North Carolina courts charge fines for seemingly everything. Defendants unable to afford a lawyer are assessed $60 before a judge considers whether to appoint one. Once a lawyer is appointed, the defendant must pay an hourly fee. If the defendant is held in jail, unable to make bail before trial, he must pay $10 a day. If he is placed on pretrial release, he must pay $15. There is a $600 fee if the prosecutor decides to test evidence at the state crime lab. Many of these charges cannot be waived by a judge. [Anne Blythe / News & Observer]

Private probation companies often levy their own fines and fees, and they jail people for nonpayment.

In Tennessee, the private probation company, Providence Community Corrections, charged people monthly supervision fees along with fees for nearly every required service, including drug tests and community service. If people couldn’t pay, they were jailed. As in Georgia, some “clients” reported selling plasma to avoid going to jail for nonpayment. [Shaila Dewan / New York Times] In September 2017, the company agreed to pay $14 million to settle a federal lawsuit accusing it of extortion and violating federal racketeering laws. [Adam Tamburin / The Tennessean]

In Montgomery, Alabama, police repeatedly ticketed 49-year-old Harriet Cleveland for driving without insurance and a license. She kept driving because she needed to drop her son off at school and go to work. Unable to pay the fines, she received two years’ probation. Judicial Correction Services then charged her $200 a month, including a $40 “supervision” fee. She couldn’t keep up with the fines, and accrued over $1,000 in private probation fees. After her two-year probation ended, she received a notice from the district attorney demanding nearly $3,000 in payment — far higher than the original fees. The DA had added a 30 percent collection fee. Afraid of arrest, she skipped court. Police later arrested her on a warrant and locked her up for a month, where she slept on the floor. [Sarah Stillman / The New Yorker]

Prosecutors charge fines and fees for their own diversion programs and, in some jurisdictions, for the prosecution itself.

In Atlanta, Marcy Willis used her credit card to pay for a rental car for her friend. He gave her cash, and then disappeared. She eventually recovered the car and returned it, but the state nonetheless charged her with felony theft. It offered the single mother of five a chance at pretrial diversion, where, after three months of classes and community service, her case would be dismissed and her record expunged. But she could not afford the $690 it would cost her to participate. [Shaila Dewan and Andrew W. Lehren / New York Times]

In Charlotte, North Carolina, police arrested Rahman Bethea for embezzling video equipment from the hotel where he worked. Because this was his first offense, he was eligible to participate in the city’s deferred prosecution program. Prosecutors would dismiss his case if he completed certain requirements. He was required to pay $899 to participate, but because he had only $100, he could not get into the program. [Michael Gordon / Charlotte Observer]

In Coachella and Indio, California, courts use a private law firm to prosecute individuals accused of violating city ordinances that carry small fines. Several months after being charged, those accused find a surprise in the mail: a bill for the prosecution. While the fine might only be a few hundred dollars, they are responsible for thousands of dollars for the prosecution. One man accused of doing work on his living room without a permit received a bill for $26,000. [Scott Shackford / Reason]

Most people are too poor to pay these fines — so they pay interest.

Known as the “poverty penalty,” fines and fees are often doubled and tripled when an individual cannot make the initial payment. In Washington State, for example, legal financial obligations average $1,347. Those unable to pay the full sum immediately will end up owing much more. The state charges a 12 percent interest rate and a yearly $100 surcharge. [Alana Semuels / The Atlantic]

2. These fines and fees can wreak havoc on people’s lives.

Being unable to pay can result in a range of penalties, including jail time and a suspended license.

The threat of jail time

In 1983, in Bearden v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled that people cannot be jailed or have probation revoked because of an inability to pay fines. In reality, judges rarely check on a person’s economic status, and for the most part, people have no lawyer to assist them in asserting their rights. [Alana Semuels / The Atlantic]

In 44 states, judges can send people back to jail if they “willfully” refuse to make payments — a loose term. Sometimes, judges lock up poor individuals because they don’t have a job, claiming their unemployment is pretext for their refusal to pay. [Alana Semuels / The Atlantic]

In El Paso, Texas, which collected $19 million in fines in 2015, the court requires people to pay 25 percent of their traffic-related debt before considering transferring it to a payment plan. If the person can’t make that high a payment, he or she is jailed. [Bobby Blanchard / Dallas Morning News]

Levi Lane was pulled over by the police on the way home from his night shift for driving eight miles over the speed limit. Police arrested him for unpaid traffic tickets — five of them totaling $3,400. Unable to pay that amount on an $8-an-hour job, the judge locked him up. Lane spent 21 days in jail. The judge never asked about his ability to pay, nor did he believe he had to do so. “I’m not required by law to ask anything,” he stated. [Kendall Taggart and Alex Campbell / BuzzFeed]

Carina Canaan also found herself in El Paso’s jail. She accrued $3,000 for driving without a license. She couldn’t pay it off, and so she spent 10 nights in jail while pregnant. But that stay didn’t wipe out all of her fees. She still owes surcharges, which prevents her from obtaining a license. Because she needs the license for certain jobs, she has repeatedly been turned down for employment. [Kendall Taggart and Alex Campbell / BuzzFeed]

Driver’s license suspensions

In the majority of states, unpaid court debt can result in a driver’s license suspension. Only four of those states require a hearing to determine whether the person is willfully failing to pay. [Beth Schwartzapfel / The Marshall Project] In 2006, almost 40 percent of suspended licenses in the country occurred because people could not pay traffic tickets or child support, or because of drug possession. [Henry Graber / Slate]

In Kansas, over 100,000 people — one in every 20 adults — had their licenses suspended for failing to pay traffic tickets. [Oliver Morrison / Wichita Eagle]

In Lapeer, Michigan, Shane Moon stopped paying his car insurance to cover other expenses when his girlfriend became pregnant. But he had to drive to construction sites to keep his job. He got pulled over and received a ticket, with a “driver responsibility fee” attached. When he couldn’t pay, his license was suspended — which came with another fee. He kept driving to work, and he kept getting pulled over and receiving tickets and fines. As of September 2017, he was homeless and still could not pay his tickets. [Henry Grabar / Slate]

In Duval County, Florida, between 2012 and 2016, 2,004 people received jaywalking tickets. Unable to pay the $65 fine for something thousands of people do every day, 982 had their driver’s licenses suspended. African Americans were disproportionately affected. While representing 29 percent of the overall county population, they comprised 54 percent of those whose licenses were suspended for jaywalking. [Ben Conarck, Topher Sanders, and Kate Rabinowitz / Florida Times-Union and ProPublica]

Losing a license because of an unpaid fee can lead to a loss of job and social services. Most people need to drive to work and some companies require a license as a prerequisite for employment. A 2007 study showed that one third of licenses suspended in New Jersey were the result of unpaid fees. Forty-two percent of people with suspended licenses subsequently lost their jobs, and half failed to find new ones. Nine out of 10 people lost income. [Henry Grabar / Slate]

Other grave losses

In Houston, a single mother earning $9 an hour received a job offer where she would make $14. But she had an outstanding warrant for nonpayment of a fine, and the employer conditioned her job offer on payment. She couldn’t afford it, and she lost the job. [Texas Appleseed / The High Cost of Jailing Texans for Fines & Fees]

A woman in her 60s lost her subsidized housing because she owed $500 from a decades-old conviction for forging a prescription. She ended up homeless. [Joseph Shapiro / NPR]

3. These fines disproportionately affect people of color.

In Ferguson, the Department of Justice determined that all levels of government — from police to city hall — targeted African Americans for hefty tickets and fines. African Americans made up 85 percent of those stopped by police for vehicle infractions carrying large fines from 2012-14, despite making up just 67 percent of the population. [Michael Martinez / CNN]

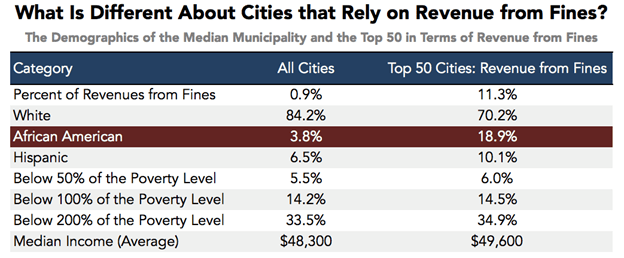

In a review of the 50 cities with the highest percentage of revenue coming from fines and fees, using 2012 Census data, Priceonomics found a direct relationship between a high African American population and high fees. It discovered that these places have African American populations five times greater than the national average. Jurisdictions with high populations of white people simply did not issue as many fines.

4. It is unclear how much revenue these fines and fees actually provide.

As a report from the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School points out, the financial benefits of fines and fees may be illusory. Most places do not track how much it costs to actually collect criminal justice debt—the cost of jail time, the cost of arrest, the cost of issuing a warrant, not to mention the economic cost to an area when someone loses a job.

5. Despite media attention on this issue, some places are doubling down on these practices.

Some judges in North Carolina have waived the state’s hefty fees, described earlier. But a 2017 state law cripples their ability to do so. Before judges show even the slightest bit of compassion toward indigent defendants, they must notify every agency entitled to the funds, which often includes corrections, police and schools. Those groups then have a right to contest the waiver. Defense lawyers and advocates worry that this could lead to fewer fee waivers—and more people locked up because they can’t pay. [Joseph Neff / The Marshall Project]

6. But the tide has started to turn. Legal challenges are mounting and some states are pushing through reform.

Around the country, lawyers are challenging the constitutionality of both debtors’ prisons and the practice of suspending licenses for inability to pay fines and fees.

In Nashville, Tennessee, lawyers successfully argued the city traps people in a permanent cycle of poverty by suspending licenses for unpaid debt. The district judge agreed, calling the practice unconstitutional. “If a person has no resources to pay a debt,” federal Judge Aleta Trauger wrote, “he cannot be threatened or cajoled into paying it; he may, however, become able to pay it in the future. But taking his driver’s license away sabotages that prospect.” [Dave Boucher / The Tennessean]

A federal judge in New Orleans recently ruled that state judges regularly violate the Constitution by jailing people unable to pay the fines those same judges had assessed. Many of the plaintiffs spent several days in jail with no hearings on their ability to pay. The federal judge described the two conflicts of interest that exist when a judge first sets the fine intended to support the court’s coffers, and then again when the judge sets penalties for the person’s inability to pay that fine. “So long as the judges control and heavily rely on fines and fees revenue … the judges’ adjudication of plaintiffs’ ability to pay those fines and fees offends due process.” [Matt Sledge / The Advocate]

In Sherwood, Arkansas, a Little Rock suburb, lawyers sued because the town locked up people who couldn’t pay fees. The suit targeted Sherwood’s “hot check” court, where officials charged thousands of dollars to people accused of writing checks with insufficient funds, even if they were just $15 short. In November 2017, Sherwood settled the case. People can now do community service to cover the fines. [Jon Herskovitz / Reuters]

7. Legislative bodies are also changing their practices.

In Washington, D.C., the D.C. Council approved legislation preventing the city from suspending licenses for missed court hearings or unpaid traffic tickets. Those with outstanding fines will have the option of paying them off through community service. This will have a significant effect: Between 2010 and 2017, the city suspended 126,000 licenses. [Reis Thebault / Washington Post]

In Maine, the legislature this year passed a bill to end automatic license suspensions for missed fines. Although the governor vetoed the bill, the legislature overwhelmingly overrode the veto, and the measure will now become law. [Reis Thebault / Washington Post]

In San Francisco, the Board of Supervisors recently voted to eliminate fees associated with the criminal justice system, including fees for probation, electronic monitoring, and being booked into jail. While people will still be subject to the state’s mandatory fees, San Francisco will now be the only city to decline to charge discretionary fees. [Joanna Weiss and Lisa Foster / Washington Post]

The California State Legislature passed a law in 2017 outlawing the practice of suspending driver’s licenses because of unpaid traffic fines. The law does not apply retroactively to the 488,000 people who have suspended licenses for unpaid traffic fines or missed court appearances. [Associated Press]

The Nebraska Legislature passed a law requiring those with unpaid fines to appear before a judge rather than automatically receiving jail time. The judge can dismiss the fines or assign community service hours. [Julia Shumway / Associated Press]