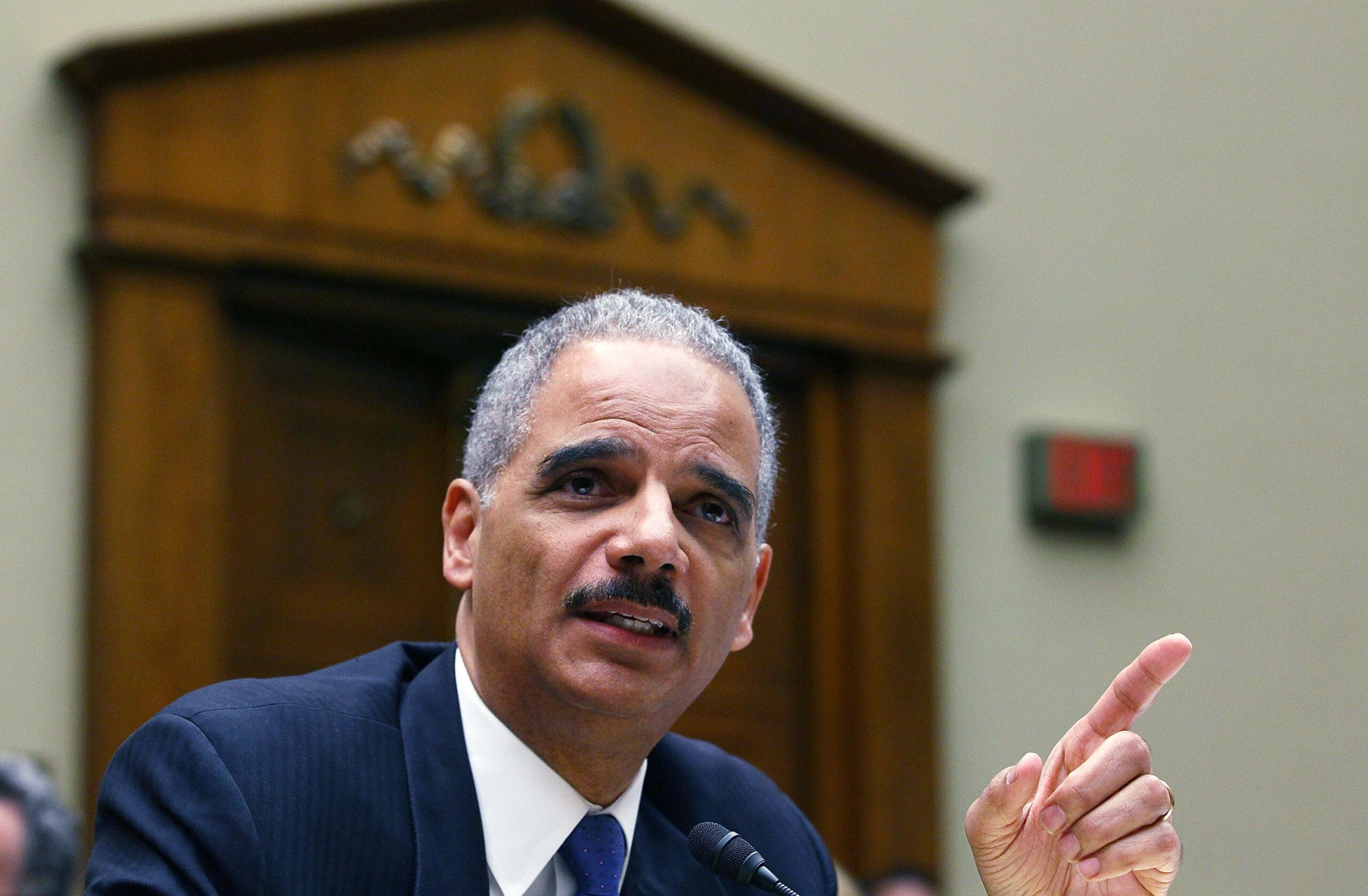

Eric Holder May Be Considering a Presidential Run. But Has His Time Passed?

As voters begin to realize that prosecutors in the world’s most incarcerated nation may not be the best people to run the government, the era of the prosecutor politician could be on its way out.

Eric Holder’s recent visit to New Hampshire has sparked speculation that he might mount a presidential run in 2020.

During a June 1 visit at the “Politics and Eggs” series at Saint Anselm College in Goffstown, the former U.S. attorney general blasted gerrymandering—“I think our democracy is under attack”—but puzzlingly endorsed the restrictive voter registration law that New Hampshire Republicans have pushed through the state legislature that now awaits review in the state’s highest court.

A 2020 run for Holder is a long shot but it’s this sort of mushy centrism that probably dooms his chances at the White House. “The Democratic Party is being pulled left … by the Bernie [Sanders] crowd,” Boston University political science professor Thomas Whalen told the Boston Herald. “They probably don’t want a moderate like Holder.”

If Holder does run, it would be on his record as head of President Barack Obama’s Department of Justice, a position he held through April 2015. It’s a record based on his toughness on crime and terrorists but also on Holder’s embrace of criminal justice reform, a matter of growing importance to the Democratic primary voters ill at ease with our world-beating incarceration rate and extremely punitive response to seemingly everything.

Holder’s credibility as a tough prosecutor is merited but his reputation as a reformer is, alas, largely nonsense despite his widely reported public statements against mass incarceration. “It’s both jaw-dropping and heart-warming to see that an issue that is that important can get people from such disparate political views together,” Holder said in 2014, “We have 5 percent of the world’s population, 25 percent of the people in incarceration. That’s not something that we can sustain.”

Holder is obviously more progressive than current Attorney General Jeff Sessions—who isn’t?—but his leadership of the DOJ was marked by risk-aversion and conservatism.

For starters, when Congress enacted the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 which reduced the sentencing disparity between offenses for crack and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1, Holder’s DOJ sent its prosecutors to court to argue against its retroactivity.

“President Obama’s Department of Justice has adopted the advocacy policy that the unfair and now reformed old crack sentencing statute should and must be applied for as long as possible to as many defendants as possible,” wrote Douglas Berman, a professor at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law. According to a recent autopsy of Obama-era criminal justice reform efforts by law professors Rachel Barkow and Mark Osler, Holder often seemed more concerned with placating the hardline career prosecutors within DOJ than granting the scope of clemency intended by Congress. “The Obama Administration’s failure to accomplish more substantial reform, even in those areas that did not require congressional action,” Barkow and Osler wrote, “was largely rooted in an unfortunate deference to the Department of Justice.”

The Holder DOJ was also aggressive in pursuing whistleblowers like Edward Snowden but also less controversial figures like Thomas Drake, who exposed National Security Agency dragnet surveillance, and John Kiriakou, a CIA torture whistleblower. Holder’s DOJ fought to uphold the broad and vague statute against “material support” for terrorism, thereby criminalizing a surprising amount of charitable giving abroad. Tarek Mehanna received a 17-year sentence for running a militant-sympathizing website that didn’t contribute to any specific crime. These and similar cases were small in number, but as law professor and formal federal defender Wadie Said argued, such national security and terrorism prosecutions cast a long shadow over the entire justice system, shifting the parameters for what is procedurally acceptable in the state’s treatment of more run-of-the-mill criminal defendants.

If Holder’s DOJ showed little mercy to drug offenders and whistleblowers, his DOJ was tender and mild with big banks after the financial asset bubble collapse. “There were no subpoenas, no document reviews, no wiretaps” is how one DOJ source described Holder’s approach to Wall Street crime. At the end of 2014, Columbia Journalism Review business reporter Ryan Chittum observed that “Holder leaves office having been far outclassed by the Bush administration even in prosecuting corporate criminals, despite overseeing the aftermath of one of the biggest orgies of financial corruption in history.”

The punitive zeal that has dealt over 2,000 Americans federal life without parole sentences for nonviolent drug crimes was nowhere to be found in the Holder DOJ’s kid-glove treatment of the masters of the universe. Indeed, in a DOJ investigation of HSBC for laundering billions of Mexican drug cartel profits, Holder overruled career DOJ prosecutors who sought criminal charges against the big bank. HSBC eventually simply settled with the government for $1.9 billion which Rolling Stone rightly noted proved that “the drug war is a joke.”

What about clemency? Big, categorical amnesties have historical precedent at the state and federal levels, including Jimmy Carter pardoning the Vietnam draft evaders, Woodrow Wilson granting clemency to Prohibition-law offenders, and Mississippi Governor Mike Conner’s “mercy courts” at Parchman Farm in the 1930s. Obama had the chance for bold and categorical measure here, but he blew it, largely because again he entrusted it to Holder’s DOJ which has hardwired institutional bias of prosecutors and former prosecutors. The nearly 1,700 commutations granted by Obama may seem impressive, but this is a trickle amid an exponentially expanded federal prison population. The Federal Bureau of Prisons held 192,170 in Obama’s last full year in office; up from 50,513 in 1988. In fact, Ronald Reagan granted clemency to a higher percentage of the federal prison population than Obama. A recently published NYU Law School study on the Obama administration’s clemency initiative concluded that it was a “bureaucratic maze that was controlled by the Department of Justice, and this design increased the likelihood of a clemency petition being denied at any given point in the process.”

Holder may have mouthed the words “mass incarceration” to the likes of The Marshall Project and others, but when it came to actually delivering impactful and badly needed criminal justice reform, he was a failure.

All of this may have less to do with Holder himself than with the inevitable consequences of putting a career prosecutor, and a federal agency full of career prosecutors, in charge of criminal justice reform. And this forces a bigger question: What structural biases are prosecutors bringing to American politics?

Unlike other wealthy liberal democracies, prosecutors play an outsize role in our political culture. From the early 20th century, the local district attorney’s office—all but four states elect their prosecutors—has been a frequent springboard to the state attorney general’s office, the governor’s mansion, the Supreme Court, the U.S. Senate. Today there’s no shortage of former prosecutors in American politics including the avuncular liberal Pat Leahy (D-Vermont) and the antediluvian Sessions.

According to a dataset made public by legal historian Jed Shugerman, who is writing a book on the rise of the prosecutor politician, our political class is saturated with crusading DAs. From 2007-17 in 38 states, his research shows that 38 percent of state attorneys general, 19 percent of governors, and 10 percent of U.S. senators have prosecutorial career backgrounds. The big presence of prosecutors in our politics goes a long way in explaining why our government has been so ready to see our collective problems (and even some non-problems) as criminal justice issues, always requiring the response of more police, prisons, and criminal law statutes.

Have we reached peak prosecutor politician? It does seem like the bloom might be off the rose. Take Senator Kamala Harris, former California AG and San Francisco DA, who now clutches the mantle of reform like a high-end scarf as she possibly looks at a presidential run. But as her lackluster reform record becomes more widely known—opposition to state sentencing reform measure Proposition 66; punishing the parents of truant children with up to a year in jail; failure to prosecute OneWest, a foreclosure mill bank that until 2015 was run by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin—she’s got a problem.

And so, too, will Eric Holder if Democratic primary voters learn that as U.S. Attorney for Washington, D.C., in the mid-1990s he initiated Operation Ceasefire “where police would stop cars on any pretext, of a minor traffic violation, speeding, tinted windows, you name it, because they wanted to search those cars for guns.” Such actions once signified “toughness” to Democrats eager to wimp-proof their right flank, especially in the post Willie Horton-era. But now, nearly 30 years later, for a growing number of Democratic primary voters, such prosecutorial harshness is, like mass incarceration and unjustified police shootings, a moral abomination. It might also be a political dealbreaker.

We surely haven’t seen the last of prosecutor politicians who grandstand and indict their way into cable news glory and donor-class cocktail parties. But a little light bulb is going on over an increasing number of Americans’ heads that ambitious prosecutors in the most carceral country on the planet are perhaps not the best people to put in charge of fixing our justice system, much less running our government.