Background Check Industry Profits Off ‘Digital Punishment,’ Despite Flawed Data

Criminal background checks have become nearly ubiquitous in many settings. But experts warn that reports can be deeply inaccurate, with some records databases containing “phantom crimes” that appear nowhere else in public record.

Tony Taylor was not anticipating becoming the center of a class action lawsuit when he attempted to rent an apartment through Airbnb in 2020. But when a standard background check by a third-party provider turned up a violent felony on Taylor’s record, the short-term rental company informed him that it had permanently banned him from using their services.

Taylor was perplexed. He’d been through countless background and credit checks before. And he thought the crime in question was well behind him: In 2014, Taylor—who spent years working in the security and personal protection field—carried his Glock handgun into Minneapolis City Hall. Unbeknownst to Taylor, he was bringing a firearm into a building with a courthouse in it. And, as such, he was accidentally committing a felony under Minnesota law, even though he says he never removed his licensed weapon from its locked holster.

Minneapolis police arrested Taylor and charged him with “dangerous weapon possession in a courthouse.” His wife, Sarah, was also arrested during the incident.

Rather than take on the costs associated with a criminal trial, Taylor decided to plead guilty. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail. As part of the plea, his crime would be reduced to a misdemeanor if he completed three years of probation.

Six years later, Taylor assumed the consequences of his run-in with the criminal legal system had been laid to rest. He had completed his probation and maintained good legal standing since the arrest.

However, Inflection Risk Solutions, a private company that provides background checks for employers and services like Airbnb, had erroneously reported that Taylor was a violent criminal. After seeing errors on his background check, Taylor requested a report for his wife, who was convicted of the same charge, to ensure any mistakes could be corrected. Her records contained the same error, and Inflection Risk had even duplicated her charges, listing her as having two violent felonies.

“At this point, I’m pissed,” Taylor said in an interview with The Appeal. “How dare you call me a violent felon. The reason why I was in security was to keep people safe, not to hurt people.”

Neither Inflection Risk nor Airbnb responded to a request for comment.

As the Taylors fought to correct the record, they would soon discover that they were far from the only ones whom private background check companies like Inflection Risk had harmed.

Over the past two decades, the widespread public availability of criminal records and court documents has helped fuel a global, for-profit background check industry worth billions. Services like Checkr, HireRight, and First Advantage claim to offer employers, landlords, and other clients a detailed snapshot of an individual’s criminal past. Some charge as little as around $25. But their assessments are often deeply flawed, in part because background check companies tend to rely on the cheapest and most easily accessible data, which is also the most prone to inaccuracies.

The growth of this industry has given rise to new forms of “digital punishment,” according to Dr. Sarah Esther Lageson, a sociologist at Rutgers University who studies the criminal record system.

“Anything from a police stop to a serious conviction can result in the same type of record: You’re either marked as a criminal or not,” said Lageson. “And so I think it’s just another outgrowth of mass criminalization in that way.”

Even when these reports are entirely accurate, they often serve to turn interactions with the criminal legal system, including minor ones, into lifelong sentences. The negative impacts of these for-profit background check services disproportionately harm Black and brown communities, following broader disparities in the criminal legal system.

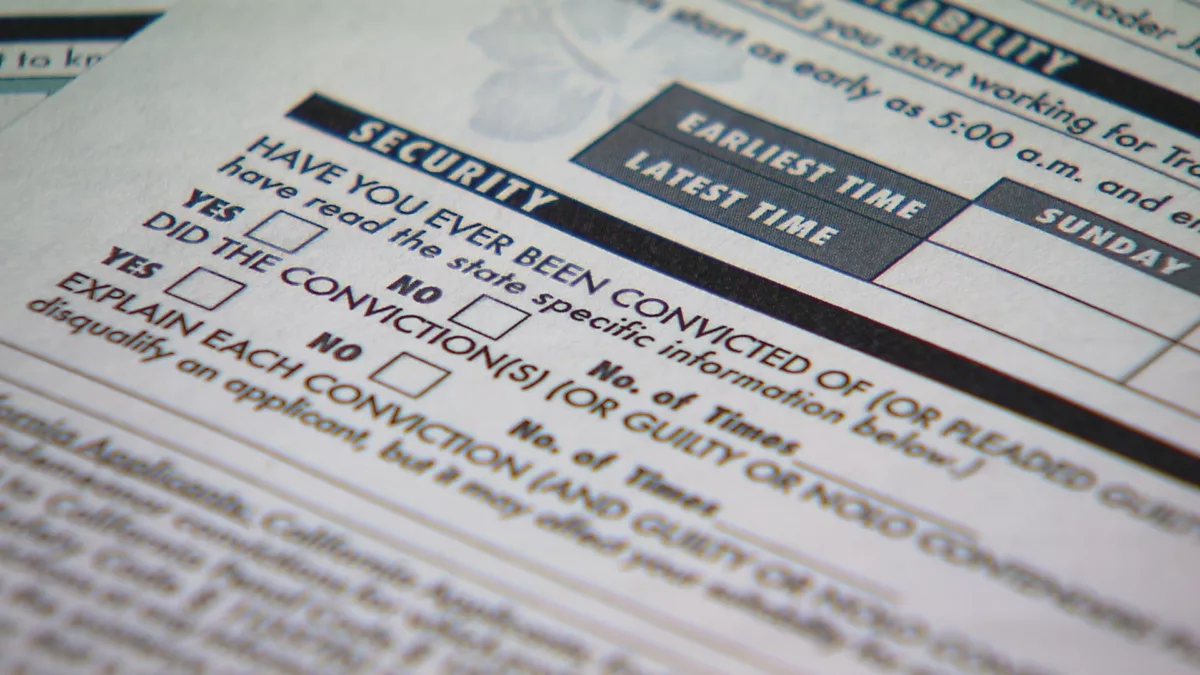

The proliferation of these companies has also undermined broader efforts to “ban the box”—or reduce the stigma of a criminal record in employment by prohibiting potential employers from asking if job candidates have been arrested or incarcerated.

As many as 1 in 3 Americans have been arrested or charged with a crime. In 2021, more than five million adults were incarcerated or under community supervision, and millions more have felony records for past offenses. The nation’s decadeslong experiment as a world leader in policing and incarceration has led to the creation of hundreds of millions of data points, which now exist in an intermingling of publicly available digital and analog documents spread across federal, state, and municipal databases—not to mention local news reports, mugshot aggregators, and citizen reporting apps often dedicated to fear-mongering about crime.

In the post-9/11 era, American anxieties fed a growing appetite for criminal record data, following newfound paranoia that everyone and anyone could secretly be harboring a devious motive or secret past.

The growing demand coincided with the rise of high-speed internet and Big Tech, which worked quickly to monetize a culture of fear, empowered by ostensibly sensible policies that treat criminal records as public records available in the name of transparency.

Against this backdrop, governments began releasing criminal record data at low cost. The resulting marketplace has birthed lucrative public-private contracts between governments and big data firms like LexisNexis. It also sparked more acute controversy, including revelations that some states were selling the felony records of children on the cheap.

As the for-profit background check industry has grown, getting a criminal background check in many settings has become as ubiquitous as providing a driver’s license or Social Security number.

Yet the background check process remains deeply flawed. The data these companies harvest from public entities or purchase from state agencies is rife with false or misleading content. Even FBI data, long considered the gold standard for criminal background checks, contains an astonishing number of errors: Between 50 to 80 percent of their records are at least partially inaccurate or incomplete, according to two reports.

Background check firms frequently make mistakes by including expunged records on their reports or by mixing up people with the same name. In many instances, reports fail to specify if an arrest ended in a conviction, or duplicate or misreport the nature of a criminal proceeding as in the case of the Taylors.

This data is so incongruent and inconsistent partly because it’s not designed to be precise, said Lageson. While an arrest may create a piece of criminal record data, for example, it “doesn’t mean there’s evidence to support it,” she said.

Lageson and Robert Stewart recently conducted an analysis of state records and two private criminal records databases, which found systematic flaws across entries. Their paper, currently under revision, found that the correct criminal history of sample records was aligned among all three datasets only 8 percent of the time.

“Almost everybody in our sample had an inaccurate criminal record in some way,” Lageson said. Either it failed to report something it should have, was missing a case disposition, or it was the wrong person, or it was reporting things that the state never recorded as having happened.”

False positives—or “orphan records,” as Lageson calls them—showed up throughout the records of the 101 people surveyed in the study. These faulty entries in private datasets fabricated a wide array of phantom crimes that appeared nowhere else in public record: Drug possession, forgery, sexual abuse, kidnapping, child neglect and cruelty, 113 weapon charges, and an astonishing 14 murder or manslaughter charges.

While that information would likely be immediately disqualifying to an employer, said Lageson, at best, they might “send you a letter saying ‘you have 10 days to remedy this.’”

To correct a faulty record, an individual would have to go to the court and pay for a paper copy of the disposition, which they would then have to return to the employer and any other reporting agencies the employer might work with. “The remedies are basically unavailable to people,” said Lageson.

Lageson said one reason background checkers turn up inaccurate reports so frequently is because many states have restrictions that protect rap sheets, which are the most accurate and up-to-date version of a person’s record under Supreme Court precedent.

Instead, data brokers sniff out the most readily available—and least vetted—information on the subject they’re assessing, often including arrest records.

“They go after the cheap stuff, which is all pre-conviction,” said Lageson. “And in general, there’s a little bit of law about what employers can and cannot do with arrest records. But I think in a practical application, if they Google you, and they see a bunch of arrests or your mugshots, they are probably not going to call you back.”

Over the past few decades, 37 states, Washington, D.C., and over 150 other cities have moved to “ban the box”—a reference to the space on a job application that allowed employers to ask about a candidate’s criminal record. These efforts coincided with a wealth of research showing a strong negative link between legal system involvement and employment and economic mobility.

While these measures have in some ways succeeded in reducing the stigma of a criminal record, for-profit background check companies can amplify the fallout from a conviction—in some cases directly circumventing “ban the box” reforms. Consequences can continue even after someone’s record has been cleared, as services sometimes still flag individuals who have negotiated an expungement or had prior convictions sealed.

These issues extend far beyond the workplace, said Sharon Dietrich, a veteran employment lawyer and litigation director for Community Legal Services in Philadelphia who has studied the criminal background check system. She recalled working with a client in her 70s who had trouble getting a volunteer position because of a criminal record dating back over 50 years.

“They did a background check and told her, ‘No, you can’t come here because of this case,’” said Dietrich. “I have clients who can’t get into senior housing because of something they did decades ago.”

While legislation like the Fair Credit Reporting Act was supposed to restrain the transmission and publishing of personal information on individuals, many of these companies do not technically identify as “consumer reporting agencies” and thus do not fall under all of FCRA’s regulations.

Some advocates have argued that the solution to this problem is to mirror “right to be forgotten” policies adopted by the European Union, which limit the public availability of personal data, including conviction and arrest data. Many EU countries only allow law enforcement to directly access criminal records and give individuals control over sharing them with external institutions.

Under these laws, “the government maintains strict controls over who is privy to criminal record information and under what circumstances, and rations access through a graduated system of disclosure depending upon demonstrated need,” writes Margaret Love, executive director and editor of the Collateral Consequences Resource Center, a research and advocacy organization that promotes criminal record reform.

How many times have they called people a violent felon? And they can’t get a job because of it?

Tony Taylor a member of a class action suit against background check company Inflection Risk Solutions.

After Tony Taylor contacted Inflection Risk about the errors in their reports, the company corrected their records. But Taylor felt the background check provider should be held responsible for its negligence.

“How many times have they done this with people? How many times have they called people a violent felon? And they can’t get a job because of it?” Taylor asked. “My story was Airbnb, but some of these [people] are doing this for employment or their housing.”

With the help of his lawyers, Taylor and nearly 1,000 other people from Minnesota brought a class action suit against Inflection Risk, claiming they had violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act by classifying numerous misdemeanors as felonies and mischaracterizing additional records.

The suit ended in a settlement, under which Inflection Risk agreed to pay $4 million in damages to nearly 40,000 people nationwide deemed to have been affected by the company’s inaccurate reporting.

Taylor says Inflection Risk offered him a substantial sum to retract his lawsuit, but he declined, feeling more accountability was necessary. “The reason why I’ve done security for so long is because I want to help people, and I have a sense of justice. And I have a sense of protection,” he said.

To Michelle Drake, one of Taylor’s attorneys, the case served as a broader rebuke of a background check industry that created a class of people meant to be viewed as irredeemable. Meanwhile, the individuals whose records are being brokered have no control over the transactions. Instead, they are beholden to profit incentives that often lead companies to “over-report” and “over-label,” with little concern for how potential mistakes could harm people, Drake told The Appeal.

“The whole industry is rotten because the whole idea behind it is ‘there are really scary people out there and you need us to protect you from them,’” said Drake. “‘And by the way, we’re gonna make a lot of money in the process.’”