To Stop Coronavirus, Places Where People Gather are Shutting Down Across California. What About Its Jails?

Activists are calling on the governor, district attorneys, sheriffs, and judges to take action to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Over the weekend, as COVID-19 cases increased nationwide, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti ordered gyms, bars that do not serve food, and movie theaters to close. He also banned dining in restaurants. California Governor Gavin Newsom has urged bars and wineries across the state to close, and restaurants to limit their capacity.

“We need to take these steps to protect our city right now,” Garcetti said when he announced the order. “Keeping a safe distance from each other literally will save lives.”

But thousands of people incarcerated in the state’s jails are forced to live close to each other, with limited access to hygienic products. About 82,000 people are incarcerated in California’s jails, according to Prison Policy Initiative.

To stop the spread of the novel coronavirus, local activists are calling on district attorneys, sheriffs, judges, and the governor to let people out and prevent fewer people from going in. So far, more than 900 people have signed an open letter to Newsom urging him to provide temporary or permanent release to as many people as possible in the state’s prisons and jails. The Appeal could not get through to Newsom’s office by phone before publication.

“Jails are by their nature going to be a place where it is very dangerous for a virus to spread, very easy for a virus to spread,” said Jacob Reisberg, jail conditions advocate with the ACLU of Southern California. “The only meaningful way to protect the health and safety of people both inside the jails and outside in the community is to release as many people as possible, especially those that are most vulnerable.”

COVID-19 is transmitted through respiratory droplets that are expelled when someone sneezes or coughs, explained David Hamer, professor of global health and medicine at Boston University’s School of Public Health and its School of Medicine. A person can also be exposed by touching a contaminated surface and then touching their face, he said.

In a jail, Hamer said, the risk of transmission is “substantial.”

People in jail are not only at a greater risk of contracting the virus, but they are also more likely to have underlying health conditions that can lead to complications. About 20 percent of people in U.S. jails have asthma, compared with about 8 percent of the general population, according to Prison Policy Initiative.

“The health care inside of our jails is woefully inadequate,” said Cat Brooks, executive director of the Justice Teams Network, an anti-police-violence advocacy group based in California. “It’s just a compounding circumstance on an already fairly dismal situation.”

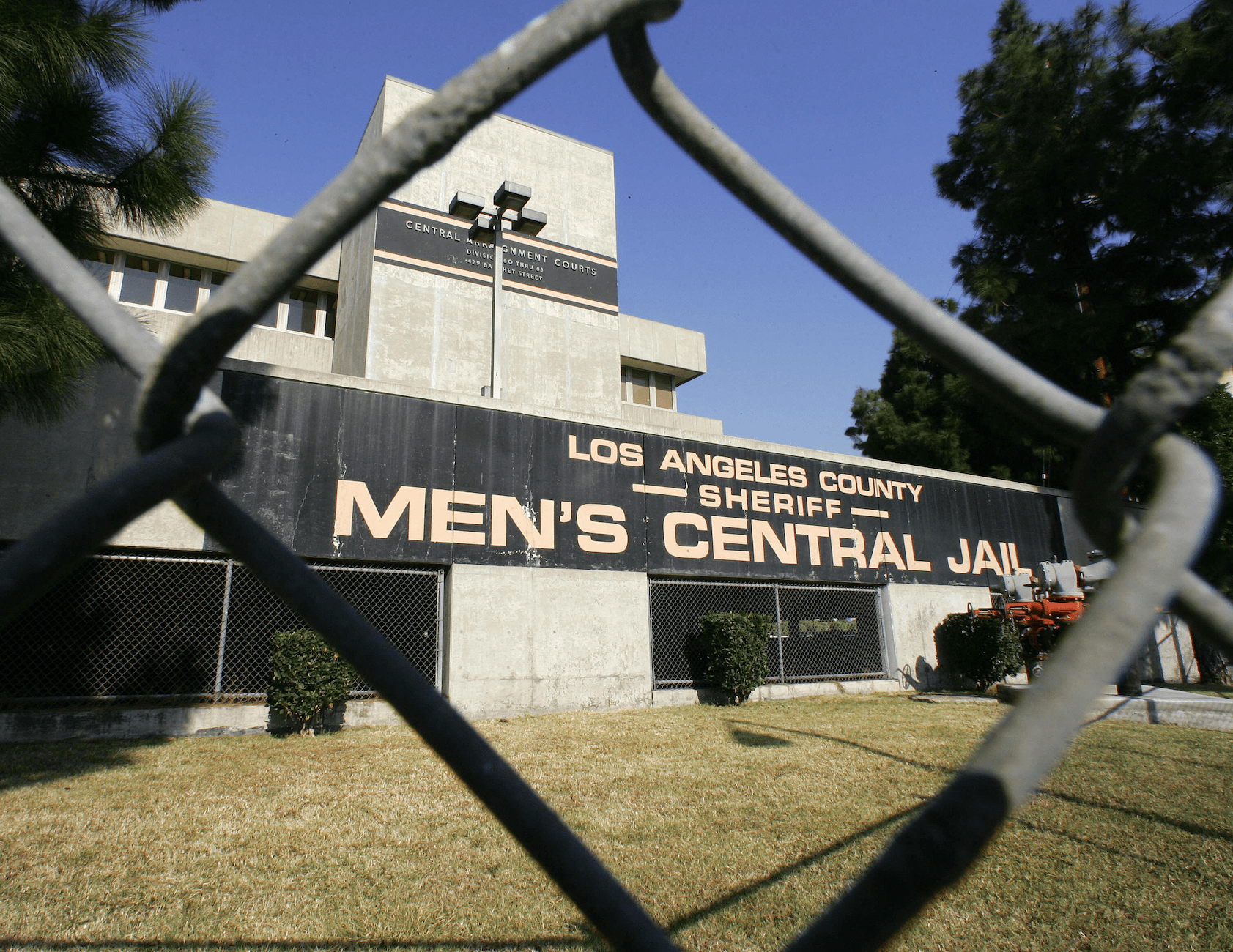

In Los Angeles County jails—the largest jail system in the country—there was an average daily population of more than 17,000 last summer, according to the sheriff’s department; 45 percent were held pretrial, according to the sheriff’s department’s quarterly report for July to September 2019. All facilities but one were over their recommended capacity.

Today, the sheriff’s department announced that in response to COVID-19, more than 600 people had been released from the jail, according to the Los Angeles Times. There are over 16,000 people still incarcerated, according to the Times. Deputies were told to limit arrests when possible, the Times reported; average arrests per day have dropped from 300 to 60.

“I’ve used my authority that I have to reduce that population,” said Villanueva, according to the Times report.

In a letter sent last week, the ACLU of Southern California had urged Los Angeles County judges and District Attorney Jackie Lacey to adopt a presumption in favor of release, without bail, for those who are vulnerable to the virus, such as people over the age of 60, pregnant women, and people with chronic illnesses, compromised immune systems, or disabilities. The DA’s office declined to comment when contacted by The Appeal last week.

“Public safety requires that as few individuals as possible circulate through the jail system,” wrote Peter Eliasberg, chief counsel at the local ACLU, and Reisberg.

On behalf of the local ACLU, Eliasberg and Reisberg also sent a letter to the Los Angeles County sheriff, urging him to evaluate and release those who are vulnerable to COVID-19 “unless there is clear evidence that release would present an unreasonable risk to the physical safety of the community.” The organization will be meeting with the sheriff’s department this week, according to Reisberg.

More than 40 groups, including the LA County Public Defenders Union and Reform LA County Jails, made similar appeals in a letter to the LA County sheriff, Superior Court judges, Lacey, and the county Board of Supervisors. The Justice Collaborative, of which The Appeal is an editorially independent project, was a signatory on the letter.

“In a context where medical care is deficient, housing conditions are squalid and individual needs are neglected, this is a recipe for the rapid spread of disease,” reads the letter.

According to the sheriff’s department’s website, those who meet “the criteria of a suspected coronavirus patient [will be] placed in isolation.” If they are confirmed to have COVID-19, they will be moved to the jail’s medical ward. As of last Friday, only attorney and professional visits were permitted at the jail.

“The Los Angeles County jail system has implemented additional cleaning, sanitation, and medical isolation procedures in an effort to protect the county jail population [from] contracting COVID-19,” Lt. Daniel W. Martin from Custody Services Division Specialized Programs in the Los Angeles County sheriff’s department told The Appeal in an email.

All incarcerated people who are entering the jail system are being screened, Martin said. Testing, if needed, is provided by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Those who may have COVID-19 will be housed in “appropriate medical isolation cells,” according to Martin. “Quarantine protocols will supersede out of cell time requirements.”

Whether they are handcuffed or shackled when they leave their cell, Martin said, “will be determined on a case by case scenario, with consideration for the inmate’s security level.”

Social distance and quarantine are integral to fighting transmission of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But in a jail or prison setting, these measures may be implemented in a punitive, harmful manner, says Maria Morris, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

“We’re definitely concerned that what will happen is that people will be put into solitary confinement,” said Morris. “We hear frequently that a person is having some kind of health crisis and they’re in an isolation cell and they can’t get any attention—they can’t get someone to come take care of them—so given that this is a virus that sometimes leads to people having difficulty breathing, that is very worrisome.”

Solitary confinement is already widely used when incarcerated patients are ill or experiencing mental health challenges. According to an investigation by ProPublica and the Sacramento Bee published last year, hundreds of people are confined in suicide watch cells at Kern County Jail. The cells, the reporters wrote, are the size of a bathroom, have a grate on the floor for use as a toilet, and a yoga mat instead of a mattress.

Philip Melendez, a formerly incarcerated activist based in California, said that in his experience in the state’s prisons, if a person reported feeling ill, they risked being sent to solitary confinement.

“Most of the time I never went to the doctor,” said Melendez, the program manager at Restore Justice. “The one time it happened, I was actually put in the hole. The same hole that is used for people with disciplinary problems so it’s the same. The same exact thing.”