In San Quentin Prison, Getting The Flu Can Land You In Solitary Confinement

Prisoners avoid admitting they are sick because they don’t want to be put in solitary, so nurses go cell to cell to take their temperatures.

Juan Moreno Haines is an award-winning incarcerated journalist and a member of the Society of Professional Journalists. This article was made possible by a grant from the Solitary Confinement Reporting Project, which is managed by Solitary Watch with funding from the Vital Projects Fund.

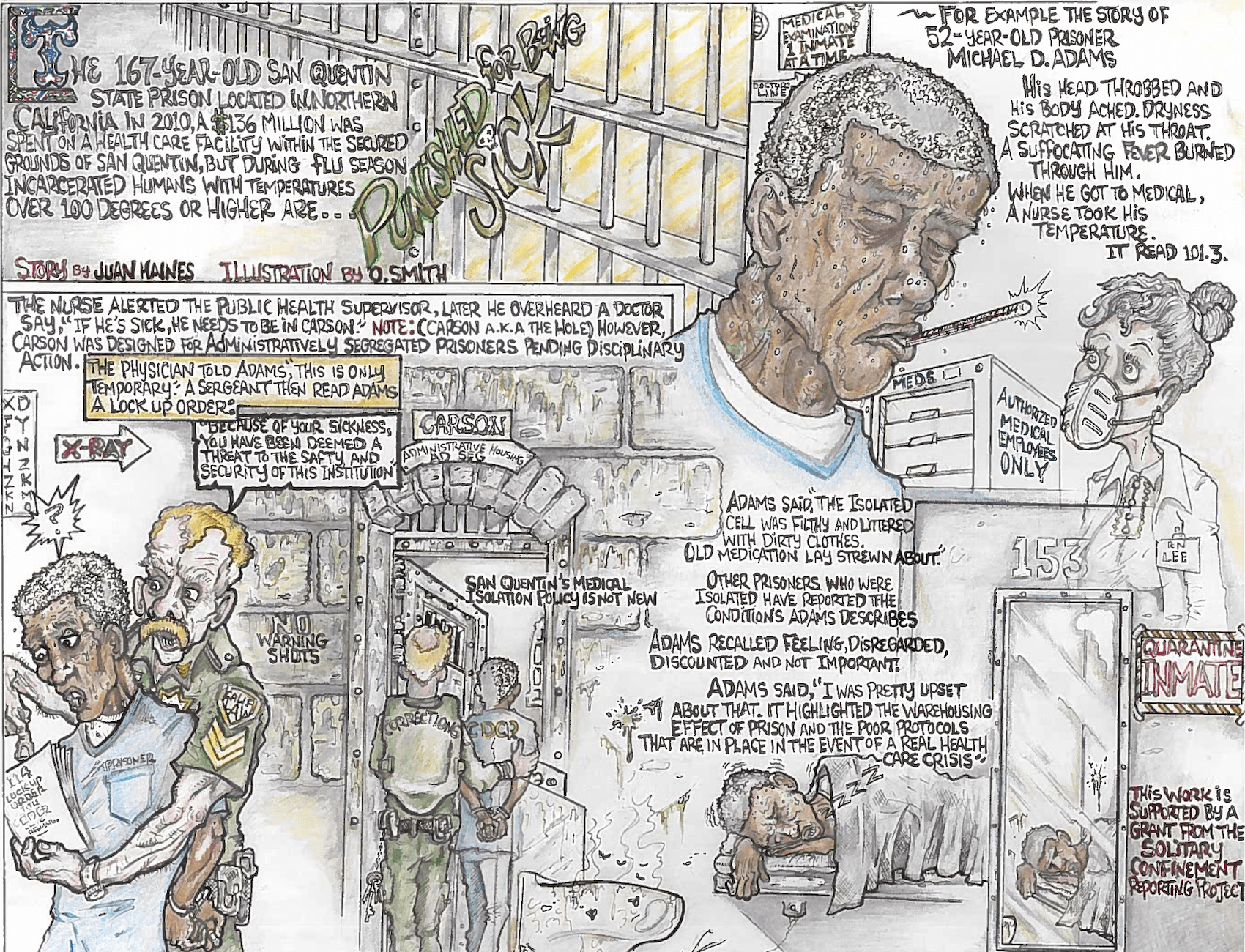

Flu epidemics, which have been common at San Quentin State Prison, can turn someone’s life upside down. Take for example the story of 52-year-old Michael D. Adams.

It was the 2019 flu season. Adams sat on his bunk in a prison housing unit. More than 700 men were held there, double-bunked in windowless cells stacked five tiers high, each smaller than the average bathroom.

His head throbbed and his body ached. Dryness scratched at his throat. A suffocating fever burned through him. But he was unwilling to seek medical help.

“Inmate Adams, cell 282, report to the front desk,” a loudspeaker blared in San Quentin’s North Block.

Adams’s discomfort turned to fear as he got off his bunk and went to a stainless steel sink attached to the cell’s back wall. He splashed water on his face. Then he spat into the cell’s shiny toilet.

“Are you all right?” his cellmate asked.

“I feel like shit,” Adams replied. Bloodshot eyes stared back at him in a handheld plastic mirror. The call to the front desk was for a scheduled eye examination. Every medical examination includes a routine temperature check. If he had a fever, there could be consequences.

Adams reluctantly got dressed. He grabbed his prison ID out of his locker. A correctional officer showed up at his cell to escort him. As predicted, when he got to medical, a nurse took his temperature. It read 101.3.

During flu season, incarcerated people at San Quentin know high fevers mean you are going to the hold. So Adams thought about raising hell, but didn’t want to make a scene.

The nurse alerted the public health supervisor. Adams was told he would be screened for the flu and was taken to the triage section of the medical department. There, a nurse took a swab from the inside of his mouth. He overheard a doctor say, “If he’s sick, he needs to be in Carson.” Prisoners in Carson are held in solitary confinement and it is known as The Hole.

“This is only temporary,” the physician told Adams.

A sergeant then read Adams a lock-up order. “Because of your sickness, you have been deemed a threat to the safety and security of this institution.” The sergeant told him that this language was the “only way” the prison could move him to Carson to increase his security to maximum.

Punished for getting sick

Like Adams, prisoners at San Quentin are regularly punished for being sick.

In early February last year, the 167-year-old Northern California prison was on the verge of an influenza outbreak. Prison officials feared an epidemic because, two years earlier, an older prisoner had contracted the flu and died.

West Block was under a quarantine that kept prisoners confined to their cells, with the exception of walking to the chow hall for their meals and to the showers once every three days.

In North Block, correctional officers escorted nurses from cell to cell to take prisoners’ temperatures. If a prisoner’s temperature was 100 degrees or higher, he was sent to medical isolation.

San Quentin’s medical isolation policy requires that patients be placed in rooms with solid doors that restrict outward-flowing air.

North and West Blocks have cells with bars, and air flows freely in and out. Since Carson has cells with perforated steel doors, prison officials use it for medical isolation. Carson, however, was designed to administratively segregate prisoners from the general population pending disciplinary action, for a prisoner’s safety, or for institutional security. It is therefore staffed with correctional officers, not nurses as in a hospital.

The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) defines medical isolation as housing patients in separate rooms with a separate toilet, hand-washing facility, soap, single-use towels, and appropriate accommodations for showering.

The standard requires that the facility have a comprehensive program that includes surveillance, prevention, and control of communicable diseases. Prisoners with contagious diseases are to be identified, and if indicated, medically isolated in a timely fashion. Infected patients are to receive medically indicated care.

NCCHC’s Infectious Disease Prevention and Control compliance indicators for respiratory isolation say that patients are to be housed in functional negative-pressure rooms that are inspected monthly to verify that the unit is clean and sanitary.

‘Anything to stay out of The Hole’

In 2010, San Quentin’s Central Health Care Service Building was completed, costing $136 million. The facility has a designed capacity of 45 medical beds.

A 2017 Pew Charitable Trusts report showed that from 2014-15, California racked up the highest average healthcare cost per prisoner in the nation at $19,796 for each of the approximately 120,000 prisoners housed in the state’s 35 prisons. The nationwide median average healthcare cost per prisoner was $5,720.

Despite the high cost, San Quentin’s new facility included only 10 rooms dedicated to prisoner patients, former Chief Medical Officer Dr. Elena Tootell told San Quentin News in 2017. “Inmate patients placed in medical beds are those who are the most vulnerable, the ones who could die from their illnesses. This is where my sickest patients are. The remaining beds are for psychiatric patients,” Tootell said.

San Quentin’s medical isolation policy is not new.

In 2017, Angelo Ramsey of North Block informed his work supervisor that he wasn’t feeling well and a nurse came to his cell to take his temperature. It read 101.3. Three other prisoners were taken along with him to Carson for having high temperatures, he said.

Another prisoner, Edward Dewayne Brooks, said he now takes precautions to avoid a repeat of a 2017 experience that landed him in Carson.

“When it’s flu season, I say to myself, ‘Here comes a lockdown,’” Brooks said in a June 2019 interview.

He added that if he feels like he might have a fever and a nurse wants to take his temperature, he fills his mouth with cold water and holds it, hoping the fever won’t register. “Anything to stay out of The Hole,” he said.

In West Block, Reggie Wimberly, then 63 years old, was sent to Carson in February 2019 after a nurse took his temperature. It registered in the triple digits. The following morning, he said, “they stripped me out, handcuffed me and took me straight to The Hole.”

Unsanitary conditions

Adams said his treatment on the way to Carson was harsh and demeaning.

“I felt humiliated walking past everyone going to The Hole,” Adams said. He said he was handcuffed tightly from behind while having to carry his property. As he passed by, prisoners asked him what was happening. He told them he had a high temperature.

Once at Carson, a correctional officer put Adams in a holding cage and gave him linen that his cellmate had packed for him. Feeling weak, he balled up his coat and rested on top of it on the floor in the fetal position.

“I felt like I was in a new prison, tried and convicted of being sick,” Adams said.

The cell he was assigned, he said, was filthy and littered with dirty clothes. Old medication lay strewn about. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation says it cleans out medical isolation cells between each use.

“I wondered if I would be contaminated, since it was supposed to be an isolation cell,” Adams said. He was exhausted. He took the old linen off the bunk, put it by the door, climbed in the bunk, and fell asleep.

The next day Adams got tooth powder, soap, and toilet paper, but he didn’t get to shower until the third day. He wanted to write home and let his family know what was happening, he said, but he wasn’t given writing material.

Other prisoners who were isolated have reported similar conditions.

Brooks said that the cell assigned to him in 2017 had snot blown on the walls and was extremely grimy and dusty. He said he wiped down the bed space with his socks and a bit of soap.

“I stayed up all night trying to figure out how to clean the cell,” Brooks said. “I’m sitting in The Hole, totally isolated. The only time I saw anyone was when an officer escorted someone to a hearing. I felt like I was in The Hole for nothing. I felt humiliated.”

And, maddeningly, he couldn’t get a consistent answer about why he was there.

“When I asked an officer, ‘Why am I being treated like this?’ he said I am here because of medical,” Brooks said. “But when I asked someone from medical the same question, they told me that they didn’t have any control on how The Hole is run.”

For Wimberly, the problem was not a dirty cell, but a very bright light that stayed on all night.

“The only thing I could do is tape a paper bag in front of it,” Wimberly said. “It was very hard to sleep and get comfortable.”

Dangerous indifference

Adams’s temperature dropped to normal after his first day in medical isolation, and he wondered how long he would have to stay in Carson. He was feeling stronger and getting restless.

Health officials say flu vaccinations may not prevent someone from contracting the flu, but being vaccinated could shorten the life of the virus in the body. Adams had taken the flu vaccination the past three years.

“I’m in The Hole and nobody is telling me what’s happening to me,” Adams said. “I determined that I would have to make a little noise to get something going on. So I asked the CO on the tier if I was slated to go.”

When the correctional officer came back with confusing information regarding his security status, Adams yelled that he wanted to talk to a sergeant.

Less than an hour later, a nurse who Adams knows came to his cell and asked him why he’s still in Carson.

“I told her that I haven’t had a temperature in four days, but I’m still here,” Adams said. Medical had cleared him to re-enter the main prison population the day before.

Adams recalled feeling disregarded, discounted, and unimportant. They didn’t care that he was well enough to leave, he thought, and he doubted they would care if he’d gotten worse.

“If I were dying at that moment, I’d die because they don’t care,” he said.

Later that day, he was released from Carson.

“It’s scary to be a man of a certain age after your health is compromised and be in a place that doesn’t seem to care if you’re dying,” Adams said. “I was pretty upset about that. It highlighted the warehousing effect of prison and the poor protocols that are in place in the event of a real health care crisis.”

In Wimberly’s view, sending people to Carson for medical isolation doesn’t make sense.

“I didn’t get a write-up or anything,” Wimberly said. “They kidnapped me and took me to The Hole. I had already lost my job at the canteen due to back injury. Now they said that I can’t get it back because being taken to The Hole is a disciplinary problem.”

According to the American Journal of Psychiatry, several U.S. and European studies on solitary confinement have found that people can suffer lasting psychiatric injuries even after short periods of isolation.

Ramsey’s cellmate, Gary T. Harrell, witnessed the profound effect that being sent to Carson had on his sick friend.

“The people the administration sends to Carson are treated like criminals, like they committed another crime,” Harrell said. “They’re stripped of everything. So why would you want to say you’re sick?”

On July 6, as this story was being produced, San Quentin administrators put North Block under medical isolation “due to multiple cases of respiratory illnesses and two confirmed cases of pneumonia,” according to a Program Status Report released at San Quentin. The state Department of Corrections later said it could not confirm there were any cases of pneumonia.

Juan Moreno Haines was alone in cell 363 in the North Block.

Correctional officers escorted nurses cell-to-cell taking prisoners’ temperatures. A nurse took Haines’s temperature, and it read 99.1. When they returned the next day, he felt a fever coming. He refused to let the nurse take his temperature. He drank plenty of water, took 200 milligrams of ibuprofen once every four hours, took one 24-hour 10-milligram tablet of antihistamine, and rested. The sickness quelled after two days. He takes the flu vaccination shot every time it’s given.