Despite Coronavirus Fears, ICE Fights to Keep a Sick Michigan Man It Can’t Deport Locked Up

ICE has adopted no policies aimed at releasing any of the 38,000 people it keeps in county jails and private detention centers across the country.

For two years, Oliver Awshana has been fighting for his life. Since ICE began trying to deport the 31-year-old refugee to his native Iraq, he has petitioned multiple courts, fought his way off a deportation flight, and endured almost a year in a Michigan county jail—all to avoid returning to the country from which he fled a decade ago, where he says he would most likely face torture.

Now, in the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic, he finds himself ill—with some symptoms consistent with COVID-19—and stuck in jail. His attorney, Shanta Driver, has petitioned a federal judge to order his release. Since jails are hotspots for outbreaks, and a court order is preventing his deportation anyway, she argues that his continued detention is dangerous and unnecessary.

“Why should we even be having this argument? If he’s sick at all, just let him go,” Driver, co-chairperson of the civil rights group By Any Means Necessary, told The Appeal.

Even under such extraordinary circumstances, however, ICE is still fighting to keep Awshana locked up.

The agency’s insistence on incarceration, even during the worst global pandemic in more than a century, reveals the rigidity of its detain-at-all-costs ethos. Though ICE has cut back on arrests and deportations in an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19, the agency has adopted no policies aimed at releasing any of the 38,000 people it keeps in county jails and private detention centers across the country—leaving, according to advocates, people like Awshana “sitting ducks” to a possibly deadly contagion.

As decarceration advocates have pointed out, social distancing enough to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is almost impossible in jails and prisons, especially in facilities where prisoners don’t have free access to soap and sanitizer. “If a pandemic enters into a facility, we know that it’s going to affect almost everyone inside that facility,” said Holly Cooper, co-director of the Immigration Law Clinic at the University of California, Davis. As an example, Cooper points to the Rikers Island jail complex in New York City. As of March 25, Rikers had a COVID-19 infection rate seven times higher than the rest of New York—the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States—according to an analysis by The Legal Aid Society.

“This is an emergency,” said Driver.

Awshana is one of hundreds of Iraqi immigrants that ICE has swept up since it began a crackdown on Iraqi communities, mostly in Michigan, in June 2017. His story is similar to most of those arrested Iraqis: He’s Chaldean—part of a historically persecuted Iraqi Christian minority—and came to the United States as a refugee in 2009. In 2017, he was convicted of one count of low-level cocaine possession and two counts of retail fraud, which stripped him of his legal permanent resident status and rendered him deportable.

In 2018, ICE issued Awshana a deportation order. He applied for asylum, but was denied later that year. In April, ICE tried to deport him, but he refused to cooperate, kicking and screaming his way off of the airplane. After the incident, ICE sent him to the Calhoun County Correctional Center in Battle Creek, Michigan.

While incarcerated, Awshana won an emergency stay on his deportation and reopened his immigration case. And in February, after nine months of court filings, hearings, and jail time, an immigration judge ordered his deportation indefinitely postponed, agreeing that he would most likely be tortured if forced to return to Iraq. Government lawyers quickly appealed the immigration judge’s decision, however, which allowed ICE to keep him detained. The next month, COVID-19 cases began spiking in the United States, and by the third week of March, Awshana was sick.

On March 16, Driver, Awshana’s attorney, filed an emergency petition in federal court asking a district judge to order her client and two other Iraqi men released from detention. Four days later, she drove to Calhoun County to check in on Awshana.

“He looked terrible,” said Driver. “He’s been telling the nurse that he has a dry, scratchy throat, and he’s got a runny nose. He’s really sweaty and he’s slightly jaundiced.”

Driver was concerned that Awshana’s symptoms were in line with COVID-19—especially since, in recent weeks, Michigan has become one of the most infected states in the country. But she said medical staff at the jail refused to test him for the virus, claiming he had a lesser illness.

Yet more than a week later, Awshana’s illness has still not gone away. On Saturday, one of his cellmates called Driver, and told her that Awshana still had the same symptoms. During the call, a transcript of which was provided to The Appeal, the cellmate said that, earlier in the week, corrections officers transferred Awshana to the jail’s intake area, where he slept overnight. In the morning, jail staff took his blood pressure, then transferred him to a new cell, this time in the second-highest security unit in the jail. According to Kate Stenvig, an organizer with Driver’s group, Awshana later confirmed what the cellmate had told them, and said the cellmate had since been transferred to a higher security part of the jail.

Calhoun County Sheriff Matt Saxton, who runs the county correctional center, forwarded The Appeal’s questions about Awshana’s case to ICE. A spokesperson for ICE referred The Appeal to the agency’s response to Driver’s petition, which the government filed on Friday. In the response, ICE argues that the jails at which Driver’s clients are detained are clean and not overcrowded. The agency also asserts that the men “have not alleged that COVID-19 has spread” to the jails, nor “that they have underlying health conditions, or are of an age, that place them at unique risk of harm.”

Driver finds that argument weak; recent data and anecdotes show that the novel coronavirus can be dangerous for all demographics, even the young and healthy. “No one should be made to stay in these facilities,” she said.

In its response to the habeas petition, ICE also argues that Awshana is subject to “mandatory detention,” a feature in U.S. immigration law that dictates that authorities must keep deportable immigrants who entered the country in a certain way, or who have certain criminal convictions (including drug offenses), detained.

Mandatory detention has been highly litigated in recent years, and there are several arguments that immigration lawyers use to try to get their clients released from it. Cooper, the immigration lawyer at UC Davis, says the argument perhaps most applicable to the COVID-19 crisis is a Fifth Amendment-based due process challenge, essentially asserting that the kind of incarceration that ICE employs is procedural, and thus illegitimate if it crosses the line into punishment or places detainees in danger—as one could argue it does during a pandemic.

Immigration detention “shouldn’t harm people,” Cooper explains. “If conditions inside of centers become punitive and rise to a level that is basically inhumane, then you have to start releasing people.”

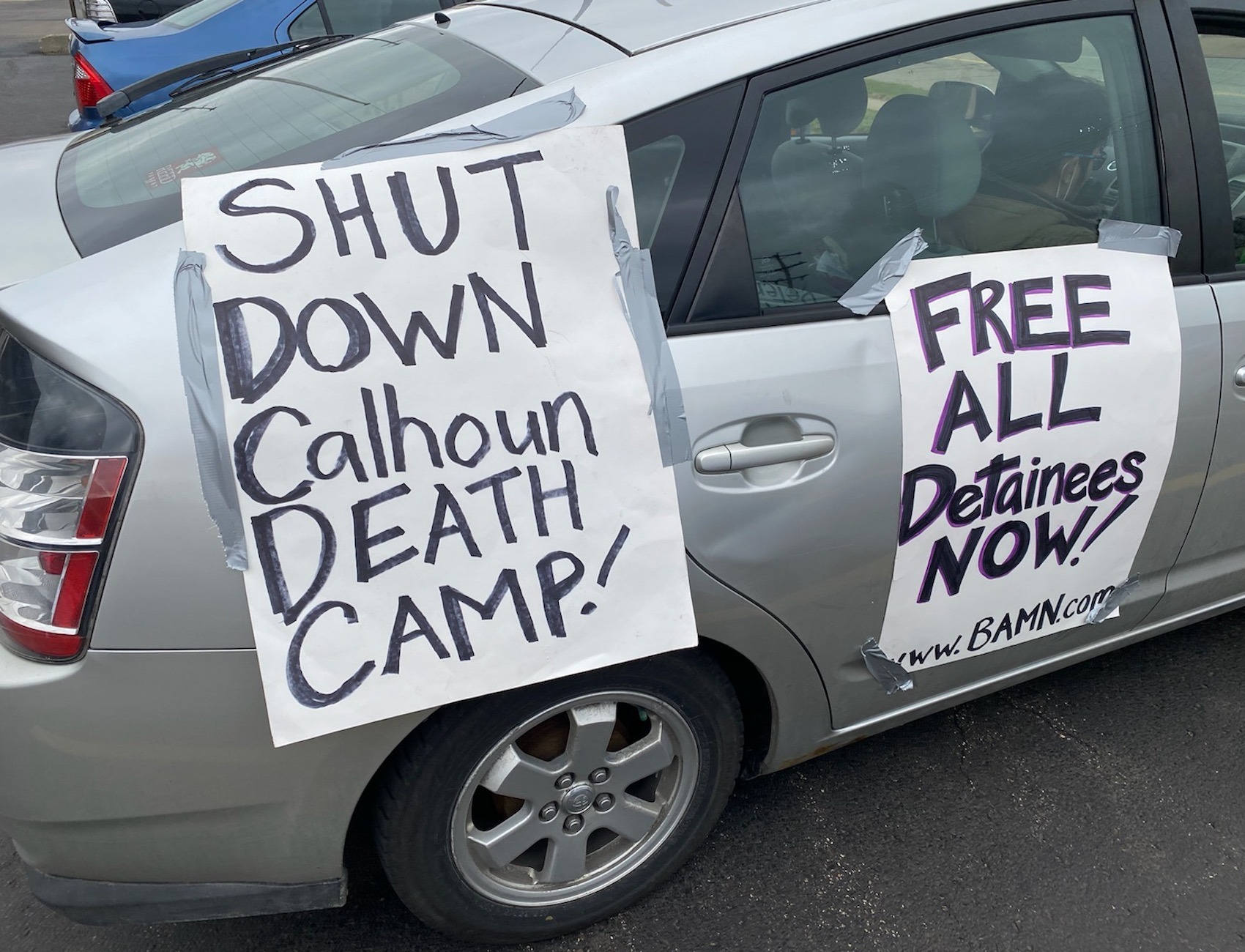

On Monday, Michigan activists, organized by Driver’s group, staged a protest at the Calhoun County Correctional Center. To maintain social distancing, they drove around the jail, honked, and yelled demands from their car windows to release those inside—their vehicles adorned with signs: “Free them all!” “Free Oliver Awshana now!”

“These are just death camps,” said Driver. “That’s all they are now.”