An Inside Look At An Ohio Police Force’s Race Problem

A white cop joked about bringing explosives to a Black Lives Matter protest in Columbus with no consequences. A black cop joked about ‘black on black’ crime and may be fired.

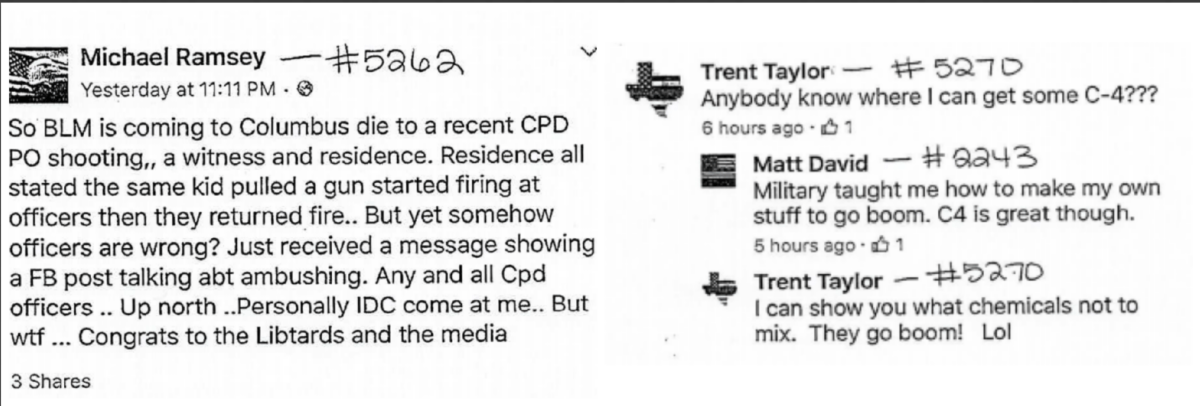

“Anybody know where I can get some C-4???” asked Trent Taylor, a white police officer in Columbus, Ohio, commenting on a fellow officer’s Facebook post about a police shooting protest in July 2016. The post was reported. But Taylor told investigators that his reference to explosives was meant to be “humorous,” and the complaint was dismissed as “unfounded.” The year before, Taylor had been involved in a fatal shooting of a Black suspect, which the department deemed justified.

Six months later, Lt. Melissa McFadden, one of the department’s few high-ranking Black officers, also made a joke, according to police records. But she is now facing far more severe repercussions that reflect the disparities in how Black and white officers are treated, she told The Appeal. During a performance evaluation with a Black sergeant, McFadden said that she could have given him a poor rating, but that she did not believe in “Black on Black crime.” The department found that this rating was an act of favoritism and created a “hostile work environment.” For this, the Columbus police department has recommended McFadden be terminated.

McFadden believes the response to her comment has more to do with what she and other officers of color say is a pattern of systemic racial discrimination in the Columbus police department. Columbus’s population is nearly 40 percent non-white, yet the Columbus Division of Police’s top leadership is entirely white.

The investigation, McFadden argues, is racially motivated retaliation for her role in helping a younger Black officer file two discrimination complaints against a supervisor in 2016, in reporting a commander’s retaliation over these complaints to the chief of police, and later filing her own discrimination complaint.

After McFadden helped the younger officer accuse a supervisor of discrimination, Columbus police commander Jennifer Knight, who is white, told a subordinate that she was going to “take [Lt. McFadden] out,” according to a lawsuit filed by McFadden. Records from the investigation show that Columbus police chief Kimberly Jacobs was informed of Knight’s comments, but then assigned a friend of Knight, Rhonda Grizzell, to oversee McFadden. In the month that followed, the lawsuit says, Grizzell, another white commander, began targeting McFadden.

Copies of emails and text messages, obtained by The Appeal, seem to support McFadden’s allegations. Some of the communications show Grizzell texting multiple officers about McFadden before they had formally filed any statements complaining about McFadden and later instructing them on how to compose a strong statement. The primary complaint against McFadden came from a sergeant nearly a month after the comment and after multiple conversations about the evaluation with Grizzell.

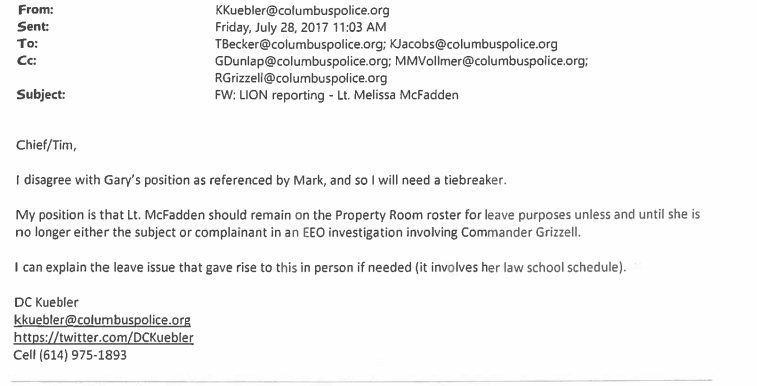

Another email shows a deputy chief recommending that McFadden, while under investigation, work in the property room “unless and until she is no longer either the subject or complainant in an EEO investigation involving Commander Grizzell.” McFadden claims that this email proves that the department has been punishing her for exercising her legal rights against discrimination, rather than solely for being the subject of an investigation.

McFadden filed her own discrimination complaint involving Grizzell and later filed a lawsuit against the department in response to this alleged retaliation.

In a phone interview, when asked about the department’s response to McFadden’s allegations, Columbus Division of Police spokesperson Denise Alex-Bouzounis said “I can tell you that quite a few of the complainants were African-American.” When pressed about the specific allegations, Alex-Bouzounis said, “I really can’t answer that because it’s part of her lawsuits against us, but I can tell you that Chief Jacobs stands by her decision to recommend termination.” The department did not respond to written inquiries submitted by The Appeal.

But four current officers and one retired officer told The Appeal that they believed McFadden’s allegations of discriminatory retaliation, and say they reflect a larger problem of racism in and outside of the department.

“They’re only going after her because she’s standing up for what’s right,” said one officer, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. Police investigators in the division “do this all the time,” said the officer. “If you’re a strong, opinionated Black officer, they’ll put you in your place quickly.”

Another current officer agreed, calling the investigation of McFadden a “witch hunt” in retaliation for McFadden helping the younger officer file a discrimination complaint. “Melissa since day one has always been outspoken and stood up for everyone’s rights, Black and white, if it’s wrong, you’re wrong, Black, white, purple, or green.”

“When you’re outspoken they treat you a different way,” said a third officer on the force. “They want you just to be quiet. If you’re not, they retaliate, that’s what they’re doing to Melissa.”

Officers say the alleged retaliation is not the only example of racially disparate treatment in the department’s disciplinary decisions.

In 2014, Eric Moore, a white officer, was accused of calling two Black officers the n-word and making statements about killing them. Colleagues interviewed about Moore said that he would also use the terms “apes” and “monkeys” when referring to Black people. Investigators in 2015 determined that Moore did use derogatory language but only gave him a written reprimand. At the time, Chief Jacobs, who is white and now calling for McFadden to be fired for her comments, said a written reprimand was sufficient for this racist language. “If I could prove a racist, sexist, homophobic mindset impacted an officer’s behavior, that’s something I can act on,” Jacobs told the Columbus Dispatch. “But it has to be actions, not thoughts.”

Last year, video emerged of Columbus police officer Zachary Rosen stomping the head of DeMarco Anderson, a young Black man. The beating took place two weeks after a grand jury declined to indict Rosen for fatally shooting a 23-year-old Black man. Jacobs recommended Rosen be suspended for three days without pay, but the city went further, choosing to fire him. Columbus’s police union, however, rallied behind the white officer and appealed the decision, getting him his job back this year.

“I promise you if that had been a Black officer, FOP [the police union] wouldn’t have rallied behind him, and he would have been fired,” said one Columbus cop.

Beyond overt retaliation, Black officers say racial disparities also manifest themselves in the department’s recruiting and promotion practices.

On the front end, officers, interviewed by The Appeal, alleged that Black applicants are being ignored and weeded out by the division’s investigative unit. A 2012 memo obtained by Pacific Standard seems to support these claims. In the memo, a Black officer reported to Chief Jacobs that the division’s background vetting team was hand-picking candidates who “look like they will make it through the process,” rather than assessing recruits based on their exam score. Despite occasional rhetoric from the city about the importance of diversity, police recruiting classes have been overwhelmingly white in recent years.

This front-end disparity helps explain why no Black officers on the Columbus police force today make it into top leadership positions, a problem which is exacerbated by exclusive, predominantly white social networks, officers say. Several officers argued that the department has failed to hire enough Black officers, especially from the community, insteading bringing in white officers, who may have either a naive or white supremacist attitude toward Black civilians.

One officer claimed that white officers like to “inflict their own ways of justice” on Black neighborhoods, referring to violent police-civilian interactions. “It’s like a bidding war to get in on these Black precincts,” said one officer. “This their legal way to affect Black people,” said the officer.

Another argued that some officers, especially white officers, come with naive intentions about helping inner city residents, but then become violent once their expectations don’t match what they have seen on television. “You’re out there every day, and the majority of things you see are bad. This job changes you in ways that you can’t see, and you can be become an oppressor. That’s even for minority officers.”

If even veteran police officers are being punished for speaking against alleged racial discrimination, other cops are unlikely to speak against day-to-day police abuse of civilians, the officers argue. “If somebody uses excessive force because of who a person is, that’s a lot of pressure against going outside and saying ‘hey this officer said this or did this,’” said another officer. “This sends a message that if you open your mouth you better get ready, don’t say anything.”

“If I’m retaliated against as an officer, and it goes unchecked,” McFadden said, “of course I’m not going to complain about citizens getting mistreated. We know what happens if we speak out. Even we are retaliated against. We’re Black, but we’re supposed to be blue.”