Deaths Mount at Scandal-Plagued Georgia Jail

Less than five months into 2024, deaths at the Clayton County Jail have already surpassed last year’s total. The local sheriff’s lack of transparency has only compounded the pain for grieving families.

A detainee at Georgia’s Clayton County Jail died in custody on May 15, bringing the facility’s death count in 2024 to at least six and surpassing the total for all of 2023, according to The Appeal’s analysis of news reports and documents provided by county agencies.

The latest deaths follow a series of scandals in recent years that have plagued the facility in the Atlanta suburbs. In 2022, former Sheriff Victor Hill was convicted of violating the civil rights of six pre-trial detainees, including a teenager, when he ordered his employees to strap them in restraint chairs for hours.

Hill’s godson, Levon Allen, became interim sheriff in 2022 and later won a special election held last year, but detainees reported that abuse and atrocious conditions have persisted at the jail under his tenure, including bed bug infestations, a lack of beds that has forced people to sleep on filthy floors, and attacks perpetrated by fellow detainees. At least four people died at the jail in 2023, according to The Appeal’s review of records.

In September 2023, U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff of Georgia called for the Department of Justice to investigate the Clayton County Jail, spurred in part by revelations uncovered in a series of Appeal investigations. At least eight detainees have died at the facility since Ossoff’s letter, according to The Appeal’s reporting. But the DOJ has yet to publicly announce any official oversight of the jail. Neither Ossoff’s office nor the DOJ answered The Appeal’s questions about the status of the request for an investigation.

On Tuesday, voters in Clayton County cast their ballots for sheriff in Georgia’s Democratic primary, in which Allen ran against three challengers. Allen fell short of the threshold to avoid a runoff and will face Jeffrey Turner, the second-highest vote-getter, on June 18.

As deaths mount at the jail, the Clayton County Sheriff’s Office has released little information to the public or grieving family members. While the department has published announcements about some jail deaths using its public alert system, it failed to do so after at least two deaths this year. The sheriff’s office did not respond to multiple requests from The Appeal for comment and would not confirm the total number of deaths at the facility in 2023 and 2024.

“We deserve to have answers,” said Annette Sanford, whose son, Jason, died in April just hours after arriving at the jail following an arrest for giving a false name.

“Other families deserve to have the answers,” she said. “They don’t feel like they have to answer to anyone. And I want them to have to answer to somebody.”

In January, 27-year-old Johnathan Pettigrew was allegedly killed by one of his Clayton County Jail cellmates, who has been charged with his murder. The sheriff’s office said in a public announcement that the victim, suspect, and a third detainee were held in a two-person cell due to overcrowding, which had left more than 300 detainees sleeping on the floor of the jail.

Pettigrew was the first detainee to die in 2024. (The man who died last week, Hakim Shahid, was also allegedly killed by a fellow detainee who has been charged with his murder.)

Eric Lee died in February, two weeks after arriving at the jail. A police report states that he poured himself a $3.29 coffee at the Piedmont Park TravelMart located inside the Atlanta airport, but only had 25 cents on him. The store’s loss prevention officer told police he wanted to press charges, and Lee was taken to the Clayton County Jail and charged with shoplifting. He was held on a $1,500 bond, according to court records.

A report provided by the sheriff’s office lists Lee’s address as “homeless.” In his mug shot, his face appears to be battered, although the arrest report states that no injuries were reported during the incident. Officials have not yet released a cause of death.

The next month, 48-year-old DeWayne Driscoll died just over a week after arriving at the Clayton County Jail, according to the sheriff’s office. He was locked up on a probation violation and scheduled to be released on Aug. 1.

His daughter, Addia Driscoll, told The Appeal that he was a “man of God” with a “great heart.” He called her every day while he was in jail.

“I buried him the day before his birthday,” she said. “His birthday was April. 6. I buried him on April 5.”

The many unanswered questions about Driscoll’s death have only compounded his family’s grief. The hospital—not the sheriff’s office—notified the family of his passing, said Addia. When the jail chaplain called Driscoll’s widow, Addie, several hours later, she told him she wanted to speak with Sheriff Allen.

Allen called her that night and told her Driscoll’s two cellmates had run to get him help because he was having a seizure, according to Addie. Driscoll had never had a seizure before, she told The Appeal.

Allen said Driscoll told medical on March 24—two days before his death—that he had issues with back pain and hypertension, and was having difficulty breathing. After a brief stay in the infirmary, he was released.

“He got out of there complaining and they sent him back to population instead of sending him to the hospital,” Addie told The Appeal.

While Driscoll was at the jail, he had been placed on medication for high blood pressure, Addie said. But Driscoll told her he’d had adverse reactions, including numbness in his feet and what felt like a mini-heart attack.

“He was saying that the medicine was making him not be able to feel his legs,” Addie said. “The last word he said is, ‘I’m not taking this medicine no more.’ And I told him, ‘Don’t take it no more.’ That was my last words to him. And that was it. The hospital called me the next day and said he was found dead in his cell, unresponsive.”

Clayton County Jail’s medical provider, CorrectHealth, has been sued multiple times for allegedly providing inadequate healthcare to its incarcerated patients. The Clayton County Sheriff’s Office pays the private, Georgia-based company more than $1.2 million a month for jail healthcare services. As The Appeal reported last year, one man, held on a forgery charge, begged for medical help for almost two months before he died. The Clayton County Medical Examiner’s Office ruled his death was caused by testicular cancer, complicated by medical neglect.

In response to questions about Driscoll’s treatment, CorrectHealth’s chief legal officer told The Appeal in an email that to protect “our patient’s privacy, we cannot provide comment regarding his specific medical care and treatment.” She added that they “send our deepest condolences to his family.”

Addie asked Allen if there was video footage to help piece together what happened to her husband, but he told her that Driscoll was inside a cell where the jail does not record video.

However, a report by the Clayton County Medical Examiner’s Office states that video footage shows Driscoll moving around a cell at about 6:39 a.m. on the morning of his death. He appeared “like he may have not been feeling well” and soon went back to bed, according to the report.

The report states that at around 8:20 a.m. a detainee went to check on him, discovered Driscoll was not breathing, and yelled down to the floor below to call medical.

Staff called 911, performed CPR, and administered Narcan, an opioid overdose reversal drug, according to the report from the medical examiner’s office. The director of the medical examiner’s office later asked the sheriff why they administered Narcan. To which the “Sheriff responded he may have been going through withdrawal. (?)” Although records The Appeal collected do not indicate Driscoll was experiencing opioid withdrawal, clinical guidelines do not recommend Narcan as a treatment for it, and the CDC warns that Narcan can cause withdrawal symptoms.

The report states that Driscoll had a history of alcohol abuse, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and sleep apnea, according to his jail file. Driscoll’s daughter told The Appeal her father did not use drugs.

EMS arrived at 8:26 a.m. and “took a few minutes to get to” Driscoll, according to the report from the medical examiner’s office. He arrived at the ER at about 9:15 a.m.—almost an hour after he was found unresponsive—and was pronounced dead at 9:17 a.m. A public announcement from the sheriff’s office about Driscoll’s death states that he had a seizure and went into cardiac arrest.

Addie said her husband was a humble, thoughtful man who was always smiling and laughing. His 7-year-old granddaughter has been taking the news of his death especially hard.

“He’s truly missed,” Addie said. “I still can’t believe it. It’s unreal.”

In April, two more Clayton County detainees died, leaving behind shocked and grieving families.

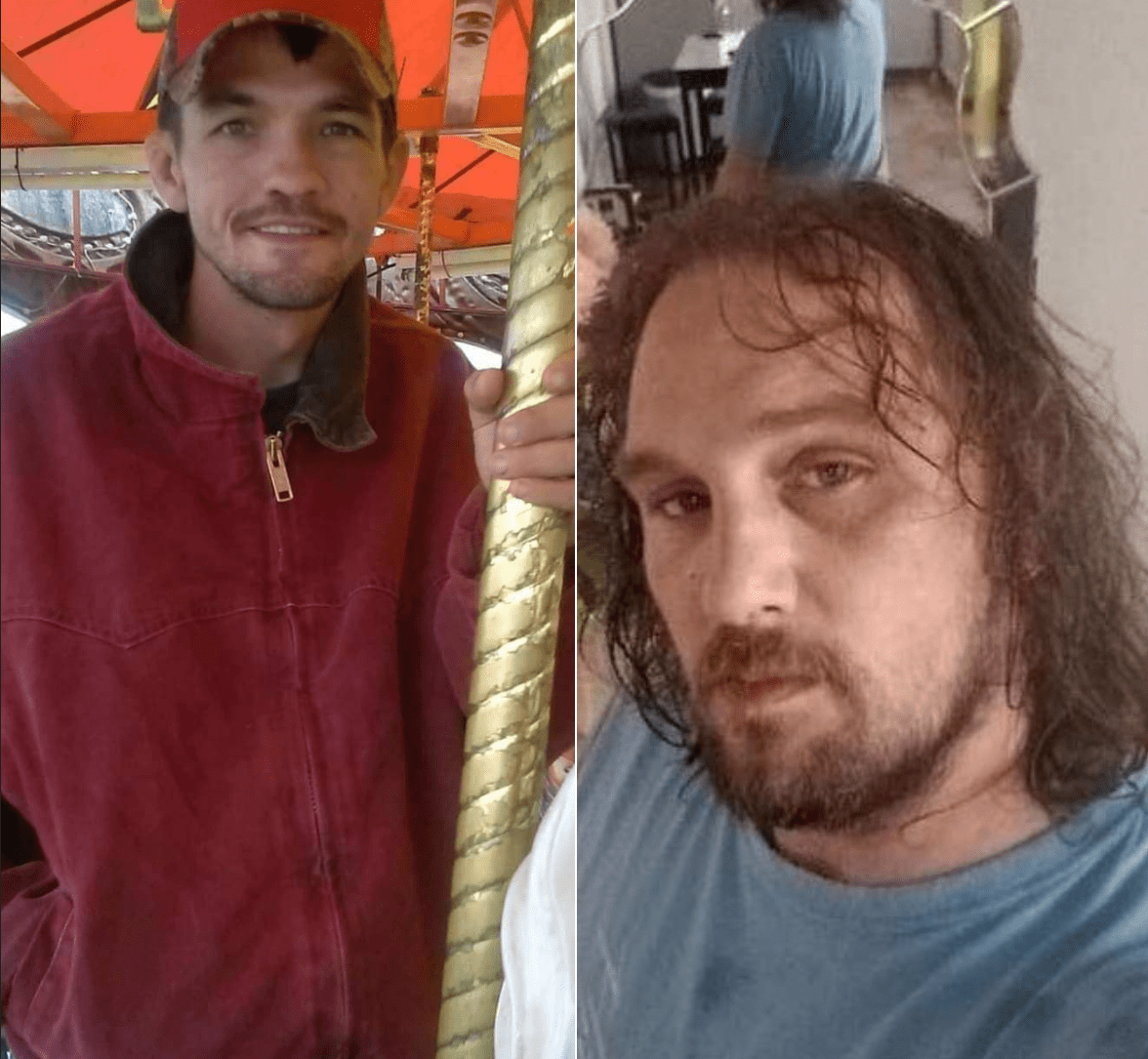

Jason Sanford, 41, arrived at the jail on the afternoon of April 5, where he told a nurse he was experiencing pain in his back and wrist, according to a report by the medical examiner’s office. Sanford’s mother told The Appeal that her son had previously seriously injured both his back and wrist.

Larry Ingram, Sanford’s older brother, said he was on the phone with Jason almost the entire time he was at the jail. They last spoke at about 5 p.m., when he told Sanford their mom had already paid his bond on a charge of allegedly giving a false name to a law enforcement officer.

But Sanford wasn’t released. About an hour later, at 6:10 p.m., he was placed in an isolation room, alone, where he could be seen via video monitor, according to the report from the medical examiner’s office.

The report states that Sanford was observed to be twitching. He stopped moving at 6:20 p.m., but medical staff and a corrections officer did not enter his room with an AED until 15 minutes later, at which point they “tried to resuscitate him.” They administered Narcan twice, and Sanford became responsive and then unresponsive after each dose, according to the report. EMS arrived at 6:45 p.m. and took him to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:18 p.m.

The sheriff’s office said in a statement that Sanford suffered “a medical emergency and became unresponsive.”

Sanford’s mother, Annette, told The Appeal that the jail chaplain who called after her son’s death repeatedly asked if he was a “drug addict.” Ingram described a similarly insensitive experience with the sheriff’s office. When he went to pick up his brother’s belongings, he said the jail gave him someone else’s clothes.

Sanford was “kind-hearted” and would help anyone in need, said Ingram. He’d spoken to his brother on the phone every night after moving to Florida four years ago.

“Now I sit at home and I ain’t got nobody to talk to,” Ingram said. “I want answers. I want somebody to be responsible for this because it is somebody’s responsibility.”

Later in April, Joseph Singleton died after he was transported to a rehabilitation center, his widow, Trisha, told The Appeal. Singleton had been locked up on a probation violation and was eager to begin treatment, she said, but “he never even made it inside.”

Upon arrival at the center, staff realized Singleton had stopped breathing during the more than 3-hour ride, Trisha said. He was taken to the hospital and declared brain dead days later.

The sheriff’s office did not respond to a list of questions from The Appeal.

Trisha said she believes there was inadequate supervision on the ride to the center.

“You’re in the same vehicle with somebody, how do you not notice?” she said. “All it takes is two seconds to call somebody’s name and make sure they respond back.”

She hopes any recordings that may exist can help fill in some of the missing blanks.

“Can you tell when he stops breathing—is it noticeable?” she said. “What are the reactions [of] people around him when it happened or at all during the ride?”

While Singleton was at the jail, he often feared for his safety, according to his correspondence with jail staff.

“I need to change housing units,” he wrote in March. “I have problem with someone here I can’t say who but please help me.” When asked for further information, Singleton replied, “They trying to make me give them money in here.” The next response from the jail staff appears to state that Singleton had been moved.

But later that month, on March 30, Singleton sent another message, writing that somebody in his dorm had just been stabbed. “Please come get me,” he wrote. On April 3, Singleton again requested help, telling staff he had been housed in a unit with the “same guy that was messing with me.” In another correspondence, he reported having bug bites that had become infected. Trisha said Singleton had described being freezing cold at the jail, not having soap, and being forced to sleep on the floor. He also said detainees had access to drugs. His reports to staff and his wife echo what detainees had previously told The Appeal about violence and other issues at the jail.

Dangerous conditions persist in county jails throughout Georgia, sometimes garnering national headlines. In 2023, the Department of Justice launched an investigation into Atlanta’s Fulton County Jail amid international outrage over the death of detainee Lashawn Thompson, driven in part by the release of images of his squalid cell and bug-bitten body. At the time of Thompson’s death, most people held in his unit, which housed individuals with mental illness, were so malnourished that they had developed a wasting syndrome typically found in people with advanced-stage cancer.

Over the first five months of 2024, the Clayton County Jail has outpaced the notorious Fulton County Jail on detainee deaths. As of mid-May, three detainees had died in Fulton County custody this year—one in January and two in April, according to the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office.

To alleviate the inhumane conditions in county lock-ups, community members have repeatedly called for police officers, judges, and prosecutors to reduce overcrowding by diverting people away from jails and releasing those who are detained pretrial on low-level offenses. But a new state law that goes into effect July 1 appears likely to take the state in the opposite direction by requiring judges to set bail for people charged with dozens of low-level charges and virtually banning charitable bail funds.

On Singleton’s last call home, he was “joking around” with their eldest son, Trisha said. They have three children together—18, 17, and 15—who “loved him deeply.” Singleton told them he was still waiting on the transport to the rehabilitation center. He had struggled with addiction for several years and was excited “about [this] being a next step for freedom, about being clean, about getting help,” Trisha said. But the jail’s failure to protect him cut that journey short.

“He won’t ever be able to go to a real rehabilitation center,” Trisha told The Appeal. “That’s not an option now. He doesn’t have a second chance. He doesn’t get it because someone couldn’t turn around and make sure he can respond back.”