The Media Frenzy Over Chanel Miller Boosts Mass Incarceration

Miller’s victim impact statement was centered in a recent ’60 Minutes’ segment on the Brock Turner case. But such statements do not heal victims, and Miller’s unfavorable comparison of Turner’s sentence to drug offenders only reinforces carceral logic.

“You don’t know me, but you’ve been inside me,” Chanel Miller said as she stood dressed in black in a recording studio reading her victim impact statement from the sentencing of former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner. In March 2016, Turner was convicted of digitally penetrating Miller in 2015 while she was intoxicated and unconscious outside an on-campus fraternity party.

Prosecutors asked for a six-year prison term, even though under California law Turner could have served a maximum of 14 years in prison. Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky imposed a six-month sentence plus three years of probation. Turner served three months, sparking national headlines and outrage about his “light” sentence as well as a recall movement that led to Persky’s ouster in June 2018.

On Sept. 22, “60 Minutes” aired an interview with Miller, formerly known pseudonymously as Emily Doe. The segment also captured Miller reading her victim impact statement for the audiobook of her memoir—”Know My Name”—published on Sept. 24. The book’s title appears to reference both her long-held anonymity and a line from her victim impact statement where she wrote that after the assault Turner told police “he didn’t know my name.”

This isn’t the first time Miller’s victim impact statement has been used for attention and ratings: On June 3, 2016, the day after Turner was sentenced, BuzzFeed published the statement and it quickly spread. It was viewed over 11 million times within four days of its publication and was later read into the congressional record by members of the House of Representatives. “Your words are forever seared on my soul,” then-Vice President Joe Biden wrote in an open letter to Miller, also published on BuzzFeed.

But centering a victim impact statement in the Turner case is oddly discomfiting: Just as a person is more than the worst thing they’ve ever done, a person is undoubtedly more than the worst thing that’s ever happened to them.

Beginning with California in 1982, all states as well as the federal government passed laws allowing victims to make statements during some part of the sentencing process. Victim advocates, prosecutors’ offices, and the Department of Justice say that victim impact statements help provide closure to victims and assist a judge in deciding on a sentence.

Victim impact statements are meant to capture the emotional impact of the crime on a victim’s life, but like Miller’s statement, they can also contain factual assertions that may not have been supported by evidence and can’t be cross-examined.

The words “rape” or “raped” appear 11 times in Miller’s statement, and Turner has been identified in countless news stories—and even a textbook—as a rapist. While Turner was initially charged with rape of an intoxicated person and rape of an unconscious person, the charges were dropped by the Santa Clara district attorney’s office. Turner was not convicted of rape but instead three felony counts of sexual assault.

In her statement, Miller uses the words “behind a dumpster” seven times, an inflammatory phrase repeated by the prosecutor throughout the trial and in news media that suggests Turner deliberately planned and concealed his actions. But the location of the assault was a relatively open space that was near a dumpster. Indeed, Turner’s appellate attorneys argued that “the site of the sexual contact in this case was an open area adjacent to residential dorms and to a basketball court—a clean, well-maintained area shaded by pine trees, typical of the sylvan Stanford campus.” (An appeals court later upheld Turner’s conviction).

Victim impact statements supposedly give victims the chance for their stories to be heard. This is understandably an attractive prospect to victims of sexual trauma who, as research suggests, may be able to heal through re-establishing a sense of control over their lives, including the ability to make decisions about when, how, and with whom they disclose the details of their assault. But the statements can also be exploited by people whose interests may not align with the interests of victims.

In Santa Clara County, where the Turner case took place, protesters and politicians alike partook in a festival of outrage sparked by Miller’s statement. Then they appropriated it by channeling everyone’s outrage toward ratcheting up punishments in the criminal legal system.

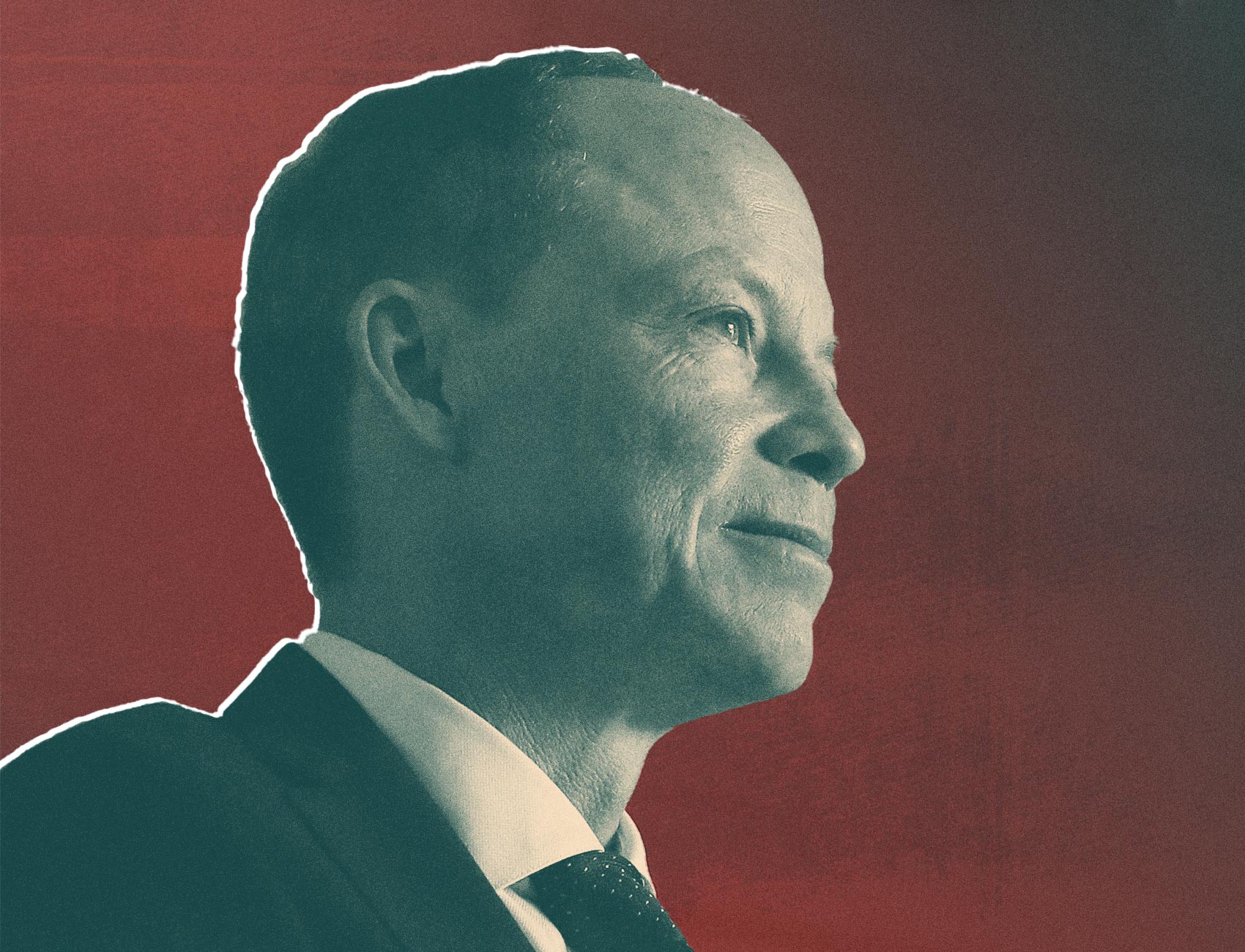

“We’ve read the letter,” Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen said of Miller’s statement at a June 22, 2016, press conference for a new bill he had sponsored that would require anyone convicted of sexual assault of an unconscious or intoxicated person to serve time in state prison. “Now let’s give her back something beyond worldwide sympathy and anger. Let’s give her a legacy that will send the next Brock Turner to prison.”

A week later, Deputy District Attorney Alaleh Kianerci testified before the California state legislature in support of the new mandatory minimum, pleading: “I’m asking you respectfully to consider this bill after reading the victim’s letter one last time. It will only take you 10 minutes. … We all need to try to protect the next Emily Doe against the next Brock Turner. It’s on us.”

It’s no surprise that Rosen’s office would find Miller’s statement useful: It echoed the carceral thinking behind mandatory minimums. “If a first time offender from an underprivileged background was accused of three felonies and displayed no accountability for his actions other than drinking, what would his sentence be?” Miller wrote. “The fact that Brock was an athlete at a private university should not be seen as an entitlement to leniency, but as an opportunity to send a message that sexual assault is against the law regardless of social class.”

Indeed, in her “60 Minutes” interview, Miller said Turner went to “county jail for three months” while “there are young men, particularly young men of color, serving longer sentences for nonviolent crimes, for having a teeny-weeny bit of marijuana in their pockets. And he’s just been convicted of three felonies.”

But long sentences don’t act as a deterrent. And decreasing punishments for everyone is necessary for a fairer, less discriminatory and ultimately much smaller criminal legal system. Mass incarceration exists not because people are locked up in “teeny-weeny” marijuana cases—people convicted of drug crimes comprise just 15 percent of our state prison populations—but because we over-punish violent crime.

Unsympathetic defendants like Turner should challenge us to think critically about the purposes of punishment as well as the assumption that long prison sentences can solve a problem like rape. Miller’s assertion in her “60 Minutes” interview—that fairness dictates that a nonwhite person’s unjust punishment means we need to increase sentencing for others—is not reformist thinking but is instead the logic of mass incarceration cloaked in feminism.

Victim impact statements that demand more punishment, like Miller’s, receive enormous media attention. But victims are not a monolithic unit. They do not always seek vengeance, and victims are often survivors of a criminal legal system that is just as cruel and punishing to them as it is to criminal defendants. And their wishes also do not always align with the interests of prosecutors. A 2011 study found support for the death penalty decreased among the families of murder victims the more the penalty was justified as a means toward retribution or closure for victims. The increasing backlash of surviving family members against the death penalty challenges the contention popular with victims’ rights advocates that criminal punishment can provide victims with closure or catharsis.

Nor are victim impact statements likely to provide a “path to culture change.”

Over the last half century, we have vastly expanded the role of law enforcement to deal with homelessness, mental health, poverty, and substance use disorder. Police departments use surveillance and occupation to supposedly predict crime and stop it before it happens. And despite access to cutting-edge technology and ever-increasing funding, police departments clear fewer reported rapes than ever. So, contra Miller, we should not further expand the carceral state under the banner of “healing.”

Nor is a punishment a means to heal. A criminal punishment does not change the consequences of violence, which can impact a person for life. Criminal courts are not designed to heal or mediate between the victim and the accused, and expecting a positive experience can set people up for a sense of betrayal that compounds the harm they’ve already suffered.

Under the punishment paradigm, Miller believed that “leniency” was granted to Turner—she used the word twice in her statement—but Turner was caged for three months in the notoriously dangerous Santa Clara County jail (there were 79 deaths there between 2005 and 2018, the seventh highest number of deaths in the state) and his sex offender registration represents a lifetime of punishment.

“He is a lifetime sex registrant,” Miller acknowledged in her statement. “That doesn’t expire, just like what he did to me doesn’t expire, doesn’t just go away after a set number of years. It stays with me, it’s part of my identity, it has forever changed the way I carry myself, the way I live the rest of my life.”

But the criminal legal system exists to determine the culpability of people accused of such crimes and punish them if convicted, which is what happened in Miller’s case. It will not ease trauma and other personal consequences of sexual assault; it may in fact deepen them.

Moreover, the length of a prison sentence cannot determine a victim’s worth, as suggested by Miller’s assertion that her life was “put on hold for over a year, waiting to figure out if I was worth something.” We should not confer a moral authority on the criminal legal system.

It’s true that for Miller, Turner “cannot give me back the life I had before that night either.” But neither can criminal punishment.

If we had a reconciliation-based or restorative justice system, participation in that process might be described as “healing.” But our adversarial system, designed to determine criminal liability and punish people, does not allow for reconciliation: It can be against the interests of people accused and convicted of crimes to admit guilt or apologize.

We can’t continue to measure justice by severity of punishment. We should encourage courts to evaluate everyone as individuals and to impose sentences tailored to each distinct person. Individualized considerations in sentencing—like Persky considering Turner’s lack of criminal history, his ability to comply with the terms of his probation, character letters from his friends, his young age and how life in a state prison might affect him—do not excuse Turner’s crime nor do they trivialize Miller’s trauma.

A criminal sentence cannot make victims whole again or undo what they have suffered. It shouldn’t, and victims shouldn’t expect it to. The best victims can expect is that the state gets it right the first time so it won’t have to prosecute the case again. The most pertinent and probing questions about the Turner case comes not from Miller’s impact statement but from Persky’s 2016 remarks at sentencing. He acknowledged that both the sexual assault and criminal proceedings had “poisoned the lives” of Miller and others—but then he asked, “Is state prison for this defendant an antidote to that poison? Is incarceration in state prison the right answer for the poisoning of [Miller’s] life?”

Meaghan Ybos is the co-founder of People for the Enforcement of Rape Laws.