Capital Punishment in the United States: Explained

To beat the clock on the expiration of its lethal injection drug supply, this past April, Arkansas tried to execute eight men over eleven days. The stories told in frantic legal filings and clemency petitions revealed a deeply disturbing picture.

In August 2018, the state of Tennessee executed Billy Ray Irick, the first man executed in the state since 2009. He had spent over 30 years on death row. As a child, Irick experienced unimaginable abuse. His mother would tie him up with a rope and beat him. Neighbors described his father as “an excessive drinker and a brutal man” who beat his wife and kids. [Liliana Segura / The Intercept]

Irick exhibited signs of mental illness as early as 6, leading some to hypothesize that he had suffered brain damage from his abuse. Around the time of the offense, he reportedly started hallucinating, telling the victim’s family, with whom he lived, that he heard the devil’s commands, who gave him “instructions on what to do.” A neuropsychologist believed Irick was likely schizophrenic or psychotic during this period, and in post-trial proceedings, the state’s own expert called Irick’s competence into question.

But the jury never heard this evidence. The defense attorneys presented no family history, called no witnesses, and presented no mental health evidence. It was only after a jury sentenced him to death for the rape and murder of a young girl that lawyers on appeal uncovered the trauma and illness that marred Irick’s life, at which point it was too late.

This August, the state executed Irick using a three-drug cocktail that experts predicted would cause sensations of “drowning, suffocating, and being burned alive from the inside out.” Dissenting from the Supreme Court’s refusal to grant Irick a stay of execution, Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned that we “have stopped being a civilized nation and accepted barbarism.”

Although America’s use of the death penalty is declining rapidly, even with fewer cases, courts are not getting better at ensuring that only the most culpable are sentenced to death, and the system is deeply broken. Below, we explore the state of the death penalty in America today.

1. The death penalty is dying.

There’s ample evidence that the death penalty is on the wane in America. Here’s what we know about why.

New death sentences are down—and prosecutors are seeking it less.

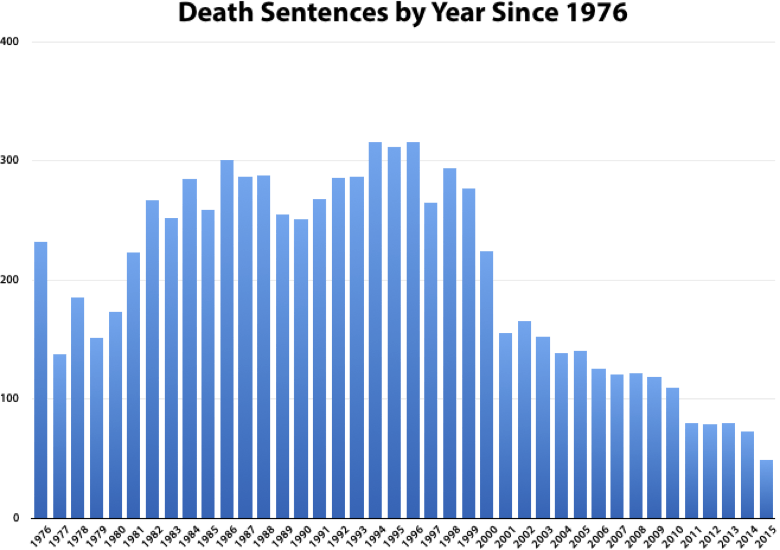

New death sentences have plummeted. In 2016, juries meted out only 30 new death sentences — the lowest number since capital punishment’s resurrection in 1972. [Mark Berman / Washington Post] In 1996, there were 315; in 2006, there were 125. That number increased slightly in 2017, where juries issued 39 new death sentences, but it was still one of the lowest yearly totals. [Death Penalty Information Center]

The data behind the 2017 numbers is telling: Responsibility for new death sentences continued to lie within a handful of outlier jurisdictions, with 31 percent of the sentences coming from three counties: Riverside, California; Clark, Nevada; and Maricopa, Arizona. In 2017, for the first time since 1974, there were no death sentences in Harris County, Texas. [Death Penalty Information Center] Put differently, out of the 3,141 counties in the U.S., only 16 sentenced five or more people to death between 2010 and 2015. Two percent of counties nationwide now account for the majority of prisoners on states’ death rows. [Emily Bazelon / New York Times Magazine]

In an interview, Frank Baumgartner, who recently co-authored a book analyzing capital punishment statistics, acknowledges district attorneys’ death penalty choices as the “key driver in the system.” [Keri Blakinger / Houston Chronicle] This makes the elections of progressive prosecutors like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia and the potential elections of Wesley Bell in St. Louis County and Joe Gonzales in San Antonio, Texas, all the more significant—counties that traditionally use the death penalty will cease doing so.

Juries are rejecting it.

But there is another reason for the decline: Juries are rejecting prosecutors’ requests to sentence people to death.

Prosecutors had not sought a death sentence in Dallas, a traditional death penalty stronghold, since 2015. But in 2017, they tried and failed twice. Jurors in the Justin Smith case indicated they were deadlocked on the penalty decision, and Smith reached a plea agreement with the prosecutor sentencing him to life in prison without parole. [Tasha Tsiaperas / Dallas Morning News] A month later, a jury declined to sentence Erbie Bowser to death. A former military veteran and special education teacher, the government accused him of killing his girlfriend, her daughter, his estranged wife, and her daughter. The defense argued that he was seriously mentally ill and suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). [Jessica Pishko / Slate] After eight hours of deliberations, the jury signaled it was hopelessly deadlocked and he received a life verdict. [Tasha Tsiaperas / Dallas Morning News]

- In the notorious Aurora, Colorado, movie theater shooting case, Colorado prosecutors sought the death penalty against James Holmes, accusing him of shooting 12 people during a screening of “The Dark Knight Rises.” After a 65-day trial, the jury deliberated for just seven hours, deadlocked and Holmes received a life sentence. The defense had argued Holmes suffered from a severe and debilitating mental illness. [Deborah Hastings / New York Daily News]

- In Wake County, North Carolina, home to Raleigh, juries have declined to sentence a defendant to death in eight out of eight cases over the last decade. After the last life sentence, the elected prosecutor stated: “At some point, we have to step back and say, ‘Has the community sent us a message on that?’” [Brandon Garrett / Slate] North Carolina overall is rejecting the death penalty: The state sentenced no one to death in 2017, making it the third year since 2012 that it had no death sentences. Only a single person has been sent to the state’s death row in the past three and a half years, and most of the state’s prosecutors are no longer seeking the death penalty. The ones who are, are failing: Juries did not impose death sentences in all four trials where North Carolina prosecutors sought the penalty in 2017. In three of those trials, juries chose LWOP, and in a fourth, they convicted of a lesser crime. [Gretchen M. Engel / Herald-Sun]

This rejection of death sentences is arguably the most revealing metric about society’s current tolerance for the death penalty. When asked to make real life-or-death decisions about a real person in a real case, prosecutors increasingly don’t seek and jurors don’t return death sentences. [Robert Smith / ACS Blog]

Executions are plummeting.

The number of actual executions has also fallen significantly. In 1999, the United States executed 98 people — the most ever executed in this country. With few exceptions, that number has steadily declined, with 35 executions in 2014, 28 in 2015, 20 in 2016, and 23 in 2017. [Death Penalty Information Center] The 23 executions in 2017 were the second fewest since 1991, and as of the end of August 2018, there have been just 16 executions. [Death Penalty Information Center]

Public support for the death penalty is declining.

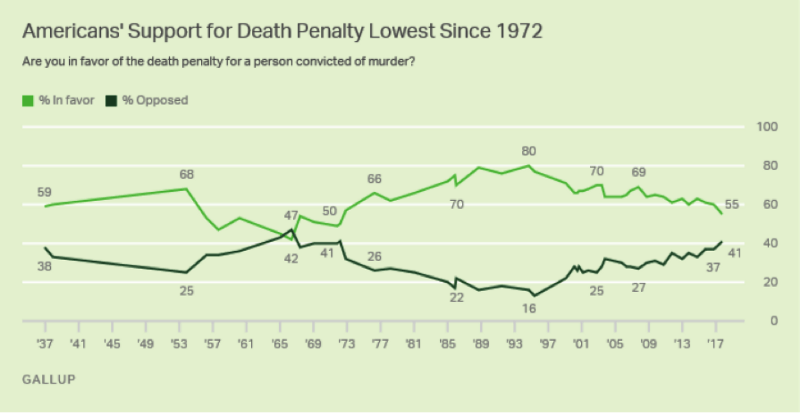

Recent polling has mirrored the decline in the death penalty’s use, with support among Americans dropping sharply. According to a Gallup poll, it reached its lowest in 45 years —in 2017, just 55 percent of Americans voiced support for its use. [Jeffrey M. Jones / Gallup]

In August 2018, Pope Francis declared the death penalty “unacceptable in all cases,” a change from the church’s previous position, holding it acceptable when considered “the only practicable way” to save lives. This could have a ripple effect in the United States, where the majority of Catholics support the death penalty. [Elisabetta Povoledo and Laurie Goodstein / New York Times]

Among Republican politicians, support for the death penalty has significantly decreased over the past seven years. In 2013, Republican lawmakers sponsoring death penalty repeal bills doubled; the figure rose to 40 sponsors by 2016. [Conservatives Concerned]

And while some voters are still in favor, the tide is turning.

- In California, voters narrowly passed Proposition 66 to speed up the state’s use of the death penalty, with 51 percent voting in favor of it. But 47 percent voted to repeal the death penalty altogether (Proposition 62), suggesting that the tide may too be changing in that state. In Los Angeles, the county with the largest number of death row prisoners, 52.3 percent voted for the repeal.

- In Nebraska, the 2016 referendum in which voters opted to repeal the legislature’s death penalty abolition bill is a source of controversy. Governor Pete Ricketts is being sued by the ACLU of Nebraska, on behalf of the state’s death row prisoners, for overstepping his executive office boundaries by donating $425,000 along with staff members’ time to the organization Nebraskans for the Death Penalty. [Josh Saul / Newsweek] According to the lawsuit, Ricketts provided the majority of total funding for the petition drive to get the referendum on the ballot in its first months. [Taylor Dolven / VICE]

2. The death penalty is broken.

Those who are executed are not the worst of the worst, despite the Supreme Court’s requirement that capital punishment be limited to society’s most culpable. In Roper v. Simmons (2005), the Supreme Court ruled: “Because the death penalty is the most severe punishment, the Eighth Amendment applies to it with special force. Capital punishment must be limited to those offenders … whose extreme culpability makes them ‘the most deserving of execution.’”

The Court has established bright line rules prohibiting the execution of certain groups, finding it cruel and unusual in violation of the Eighth Amendment : the insane [Ford v. Wainwright (1986)], the intellectually disabled [Atkins v. Virginia (2002)], and juveniles under 18 [Roper v. Simmons (2005)].

And yet numerous cases arise where people may be intellectually disabled or insane, but are nevertheless on death row. The vast majority of those executed in 2017 suffered from some form of impairment. Twenty of the 23 men had one or more of the following impairments: significant evidence of mental illness; evidence of brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range; serious childhood trauma, neglect, or abuse. All eight of the men who were under 21 at the time of their capital offenses had experienced serious trauma. [Death Penalty Information Center]

Many argue — in court pleadings and in the media — that serious mental illness,intellectual disability, or mental decline because of aging should also render people ineligible for the death sentence. Several states, including Ohio, Indiana, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, have or are considering legislation proposing such a rule. [Bob Taft and Joseph E. Kernan / Washington Post] A 2014 poll showed that Americans oppose executing the mentally ill by a margin of 2–1. [DPIC]

And yet death row is replete with those suffering from serious mental illness, trauma, and other impairments. A study by Frank R. Baumgartner and Betsy Neil found that those executed between 2000 and 2015 suffered from serious mental illness at a far greater rate than those in the general population. And 39.7 percent experienced childhood abuse, compared to 1 in 10 kids in the U.S. [Frank Baumgartner and Betsy Neil / Washington Post]

- Arkansas came close to killing Bruce Ward, who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and believed he would “survive the triple lethal injection and walk out of the prison to fabulous wealth and public acclaim, then go on to found an evangelical ministry that will spread God’s love through the power of his preaching.” [Ed Pilkington / The Guardian] The Arkansas Supreme Court stayed the execution over the state’s objection. [Max Brantley / Arkansas Times]

- Texas is trying to kill Andre Thomas, a man who gouged out his own eye and ate it after receiving the death penalty. He had a lengthy history of mental illness —he started hearing voices at age 9; had multiple suicide attempts, also starting at 9; and as an adult, started putting duct tape over his mouth because, he said, God told him not to talk. He also claimed he heard voices of God dueling with the voices of demons. [Michael Hall / Texas Monthly]

- Ohio plans to execute 23 men over the next four years. Eighty-eight percent of these men have some combination of significant mental impairments, disabilities, brain injuries, trauma resulting from horrific childhood abuse, or potential intellectual disabilities. [Prisoners on Ohio’s Execution List / Fair Punishment Project] David Sneed is one of the men Ohio plans to execute. According to court documents, he has “severe manic bipolar disorder and a schizo-affective disorder involving hallucinations and delusions.” Doctors initially found him incompetent to stand trial until they administered psychotropic drugs, after which he became a model prisoner. As a child, he suffered from physical abuse and repeated sexual abuse by his foster family, by someone at his elementary school, and by his mother’s friend. [Ohio Report / Fair Punishment Project]

- In Alabama, Vernon Madison was sentenced to death even though parts of his brain are essentially dead due to a stroke. He is incontinent, has slurred speech, impaired vision, and cannot walk without assistance. He has both dementia and amnesia, and does not remember the crime for which he is sentenced to die. In 2018, the Supreme Court issued a last minute stay of execution, over the dissent of three justices [S.M. / The Economist]

Prosecutors also keep putting the innocent on death row.

As of Oct. 17, 2017, 160 people have been exonerated from the nation’s death rows, and numerous executions have taken place despite strong evidence of innocence. According to one study, 1 out of every 25 people sentenced to death is most likely innocent. [Pema Levy / Newsweek]

- In California, despite recent attempts to speed up the death penalty, Vincent Benavides Figueroa was recently exonerated after spending 25 years on death row. He had been convicted of raping, sodomizing, and murdering his girlfriend’s 21-month-old daughter, but medical experts who testified at trial recanted their testimony, stating there was zero evidence the girl was “raped to death.” They acknowledged that they reviewed incomplete medical records at the time of trial, records that omitted the fact that many of her injuries actually occurred during initial attempts to save her life at a hospital. As the Los Angeles Times pointed out, had Proposition 66 been in effect at the time of Mr. Benavides’s conviction, he would almost certainly have been executed. [Radley Balko / Washington Post]

- In Illinois, Gabriel Solache was exonerated in 2017 after a judge overturned his conviction and death sentence for a stabbing-murder during a home robbery. With no physical or eyewitness evidence tying him to the case, the prosecution relied almost entirely on his confession. But the judge found that the disgraced Chicago detective Reynaldo Guevara told “bald-faced lies” about whether he beat a false confession out of Solache during a three-day interrogation where Solache received little sleep, drink, or water until he incriminated himself—a “confession” transcribed entirely in English even though Solache only spoke Spanish. Upon release, ICE immediately seized Solache. [Nereida Moreno / Chicago Tribune]

- In Louisiana in 2017, prosecutors dismissed charges against Rodricus Crawford, who had been put on death row in 2012 for allegedly killing his 1-year-old son. Autopsy results showed bronchopneumonia in the baby’s lungs and sepsis in the blood, but led by notorious (and now disgraced) prosecutor Dale Cox, the government put on testimony that Crawford suffocated his baby. After his conviction, numerous experts showed the child died of natural causes. [Rachel Aviv / New Yorker]

Race clearly plays a role in the imposition of the death penalty.

In 1983, David Baldus found that defendants accused of killing white victims were 4.3 times more likely to receive a death sentence than those accused of killing a Black person. [Adam Liptak / New York Times] That trend remains true: Recent reports in Pennsylvania, Florida, and Oklahoma found that death sentences are more common when the victim is white and less common when the victim is Black.

The race of the defendant featured prominently in two capital punishment cases that made headlines in 2017:

- In Texas, Duane Buck was sentenced to death after an expert witness testified Buck would be dangerous because he is Black. The Supreme Court reduced his sentence. [Alex Arriaga / Texas Tribune]

- Georgia is fighting hard to execute Keith Tharpe notwithstanding a juror’s admission that he voted for death because Tharpe is Black, stating he “wondered if Black people even have souls.” The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals recently declined to hear the case on procedural grounds. [Bill Rankin / Atlanta-Journal Constitution]

3. The death penalty is in chaos, largely because of unconstitutional laws.

Many states are struggling after utilizing laws around capital punishment that violate the Constitution.

- Florida currently has 346 people on its death row, and now it must decide what to do with many of those cases after courts upended its sentencing scheme. In 2016, in Hurst v. Florida, the Supreme Court struck down Florida’s death penalty statute that made a jury’s decision of life or death only a recommendation and allowed a judge to override it. [Harry Lee Anstead / Tallahassee Democrat] In October of the same year, the Florida Supreme Court found that the state’s revamped law, which did not require unanimous jury verdicts, was unconstitutional. [Bill Chappell / NPR] That left prosecutors and courts with the task of deciding what do with about 285 cases — nearly 75 percent of the death row population at the time. [Larry Hannan / Slate] But whether those prisoners get relief depends largely on a date because the unanimity jury requirement is retroactive only to 2002. [Nathalie Baptiste / Mother Jones] As a result, in October 2017, the state executed Mark Lambrix, even though the jury in his first trial voted only 8-4 in favor of death, and then in the second 10-2. [Jason Dearen / Orlando Sentinel]

- Alabama could be next. Alabama does not require unanimous death verdicts, and some experts predict that soon, the state will be in the same place as Florida. [Op-ed: Scott Martelle / Los Angeles Times] Alabama already took major action to bring its capital punishment scheme into constitutional compliance, passing a bill eliminating judicial override in 2017. [Death Penalty Information Center]

- Changes are also afoot in Texas. In March 2017, the Supreme Court declared Texas’s scheme for evaluating intellectual disability unconstitutional (Moore v. Texas). That test, which one judge linked to the character Lennie in John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, lacked any basis in science and medical standards. [Robert Barnes / Washington Post] Prosecutors asked the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the highest criminal court, to change Moore’s death sentence to a life sentence, and agreed that he is intellectually disabled when evaluated according to current medical standards. [Jolie McCullough / Texas Tribune] Using new, more scientific standards for evaluating intellectual disability, the court found that Moore, who dropped out of school in the ninth grade and still struggled to understand the days of the week at age 13, still did not meet the definition. [Jolie McCullough / Texas Tribune]

4. Lethal injection may be torturing people.

In execution after execution, people are awake as their lungs shut down. Most states use a three-drug cocktail to execute people. The first drug, historically an anesthetic, renders you unconscious; the second drug, pancuronium bromide, stops breath and acts as a paralytic; and the third drug, potassium chloride, stops your heart from beating. [DPIC] But lawyers and experts have argued that this is not fail-safe, and, although the Supreme Court has rejected challenges, evidence shows they are right.

Most states use midazolam for the anesthetic. It is unclear if midazolam reliably causes unconsciousness; once the second drug is administered, “the prisoners will be paralyzed, unable to move a muscle, unable to indicate in any way if they are experiencing the suffocating effects of the paralytic and the searing pain of the potassium chloride.” [Op-ed: Ty Alper / Los Angeles Times]

- Oklahoma infamously botched Clayton Lockett’s 2014 execution; he died 43 minutes after administration of a cocktail of midazolam, bromide, and potassium chloride. During that time, he raised and jerked his head, repeatedly tried to speak, groaned, and writhed. [Katie Fretland / The Guardian] The state then imposed a moratorium on executions and convened a commission to investigate. In April 2017, the commission recommended extending the moratorium until “significant reforms” are instituted. [Tracy Connor / NBC News] The state recently announced, however, that it has “finalized” its new three-drug cocktail. [Michael Cook / BioEdge]

- In Arkansas in April 2017, Marcel Williams arched his back and breathed heavily during his execution. [Ed Pilkington and Jacob Rosenberg / The Guardian] Later the same week, a reporter witnessing the execution of another prisoner, Kenneth Williams (no relation to Marcel Williams), described him “[c]oughing, convulsing, lurching, and jerking.” The reporter said, “It was clear that he was in trouble. It was clear that he was striving for breath.” [Liliana Segura / The Intercept]

States are also experimenting with new drug combinations — but those are also causing problems.

- In Ohio, executions had been on hold since Dennis McGuire’s botched 2014 execution, using a two-drug combination that included midazolam. That has ended, and the state is using midazolam, rocuronium bromide, and potassium chloride. [Jackie Borchardt / Cleveland.com] But during Gary Otte’s September 2017 execution, according to his lawyer, Otte appeared to be in pain after the administration of midazolam and looked like he was struggling for air. His lawyer also noted that Otte was crying. [Eric Heisig / Cleveland.com] Ohio encountered further controversy when it had to call off its November 2017 execution of 69-year-old Alva Campbell after 30 minutes of struggling to find a vein. Campbell’s lawyers had warned that an exam failed to find veins suitable for IV insertion in arguments that Campbell was too ill to execute. [Andrew Welsh-Huggins / Associated Press]

- In Alabama, officials similarly called off Doyle Lee Hamm’s execution in February 2018 after the team spent several hours probing him and jabbing him in search of a usable vein, and even punctured his bladder, penetrating his femoral artery. [Roger Cohen / New York Times]

- Nevada is trying to use a brand new drug combination: the opioid fentanyl; the sedative midazolam and a paralytic, cisatracurium besylate, to execute Scott Dozier. But the state has twice stayed his execution after the judge forbade the state from using the paralytic. Most recently, the execution has been stayed after Alvogen Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures the midazolam, sued because it does not want its drug used in executions. [Maurice Chammah / Marshall Project]

- In Nebraska, the state used fentanyl as a painkiller, followed by cisatracurium besylate as a paralytic, during Carey Dean Moore’s 2018 execution. This was a totally new and untested procedure. One expert predicted Moore would be “aware as he develops organ failure and, as a consequence of the paralysis caused by cisatracurium,” would “die by choking to death.” [Kashmira Gander / Newsweek]

A few justices are troubled by these botched executions. Dissenting from the Supreme Court’s refusal to intervene in Alabama’s execution of Thomas Arthur earlier this year, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, called midazolam-centered execution protocols “our most cruel experiment yet.” [Mark Joseph Stern / Slate] So are companies. Drug companies across the world are trying to keep states from using their products in executions; Pfizer is one famous example. [Erik Eckholm / New York Times] Johnson & Johnson is another. [Carolyn Johnson / Washington Post]

Amid this controversy, states are trying to keep their drugs and suppliers secret. In Arkansas in August 2017, the state paid $250 cash for four vials of midazolam from an unknown source, enough for two executions. [Taylor Dolven / VICE] Controversy also brewed after the Arkansas Department of Corrections director revealed that one of the drugs used — potassium chloride — was “donated” to her after she drove her car to pick it up from an unnamed supplier. [Jacob Rosenberg / Arkansas Times]

5. Conditions of confinement on death row are cruel and unusual.

Along with the problems of execution, the lives of prisoners on death row also deserve scrutiny. The majority of death row prisoners are held in solitary confinement. Of the more than 2,700 state prisoners currently condemned to death, 61 percent are isolated for 20 hours or more a day. In Texas, death row prisoners spend up to 23 hours per day alone in an 8-by-12-foot cell with virtually no human contact or exposure to natural light. For 14 years in Arkansas, Bruce Ward, suffering from schizophrenia, was held every day in a 12-by-7.5 cell with a toilet and shower. Guards passed his meals in through a slot. He was permitted one hour per day in another enclosed “exercise” cell, although for a decade he refused to go there. [Ed Pilkington / The Guardian]

These conditions have devastating psychological effects. The isolation and sensory deprivation drives some prisoners to insanity: They suffer from delusions and hallucinations, mutilate themselves, and experience psychotic episodes in which they attempt suicide or smear the walls of their cells with their blood and excretions. The suicide rate in solitary is five to 10 times higher than it is in the general prison population. [Nathaniel Penn / GQ]

Extended time on death row may amount to cruel and unusual punishment. Although the Supreme Court has rejected this claim, which is based on a 1995 case (Lackey v. Texas), Justice Breyer has signaled a commitment to it, lodging a number of dissents from denials of certiorari. Regarding the long delay at issue in Foster v. Florida, he wrote: “[Twenty-seven] years awaiting execution is unusual by any standard, even that of current practice in the United States, where the average executed prisoner spends between 11 and 12 years under sentence of death.” [David Savage / Los Angeles Times]

6. The fallacy of clemency.

Clemency is almost never granted to people on death row. Some believe clemency is the “fail safe” method to make sure we do not execute the innocent, the insane, or those who have not received a fair trial. The late Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that clemency was necessary because “[i]t is an unalterable fact that our judicial system, like the human beings who administer it, is fallible.” But in reality, clemency is almost never used, and it is sometimes not even controlled by an elected official accountable to the people.

- In Texas, for example, the politically appointed Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles must recommend parole before the governor can grant it. The board is not required to hold a hearing on a clemency petition, and during the six years that George W. Bush was governor, none of the 152 people executed received one. Since 2001, the state has executed 314 people while the board has recommended clemency just six times. Idaho, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arizona operate similarly. Georgia keeps its clemency proceedings secret, making it impossible to know how they make decisions. [Jess Stoner / The Morning News]

- In Florida, there has not been a commutation since 1983. The state has put 96 people to death since 1979, and only six were commuted — in four of those, juries had voted to spare their lives but a judge overrode that decision. [Editorial Board / Orlando Sun Sentinel]

7. What’s next for the death penalty?

While thousands of people remain on death row, elected officials are increasingly moving to end it.

Thirty-one states, the District of Columbia, the federal government, and the military have all turned away from executing people. Twenty-three states and D.C. have either abolished the death penalty or seen their governors impose moratoriums. Four more jurisdictions (New Hampshire, Kansas, Wyoming and the military) have executed one or fewer people in the last 50 years, and six other jurisdictions (the federal government, Idaho, Kentucky, Montana, Nebraska, and South Dakota) each executed three people in the past half-century.

Governors in Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Colorado have vowed not to allow any executions during their terms. [DPIC]

- In 2013, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper granted a temporary reprieve to Nathan Dunlap, one of the state’s three death row inmates . Hickenlooper called Colorado’s system of capital punishment “imperfect and inherently inequitable” and called it “highly unlikely” that he would reconsider the death penalty for Dunlap. In a published order, he wrote that “[i]t is a legitimate question whether we as a state should be taking lives.” [Karen Augé / Denver Post] Hickenlooper also noted that, in Dunlap’s case, three jurors later said they might not have supported the death penalty if they had known Dunlap was bipolar. [Kirk Mitchell and John Frank / Denver Post]

- Oregon Governor Kate Brown announced in 2016 she would continue the death penalty moratorium imposed by her predecessor due to “serious concerns” about the “constitutionality and workability” of Oregon’s death penalty statute. [Tony Hernandez / The Oregonian]

The Supreme Court also plans to take up two death penalty-related cases in fall 2018. In Madison v. Alabama, the Court will consider whether states can execute people who committed murders but, due to cognitive dysfunction, no longer remember their crimes. The second case, Bucklew v. Precythe, deals with whether a prisoner’s medical condition could render execution by lethal injection “cruel and unusual.” [Garrett Epps/The Atlantic]