Can Police Opposition Overturn Parole Reform?

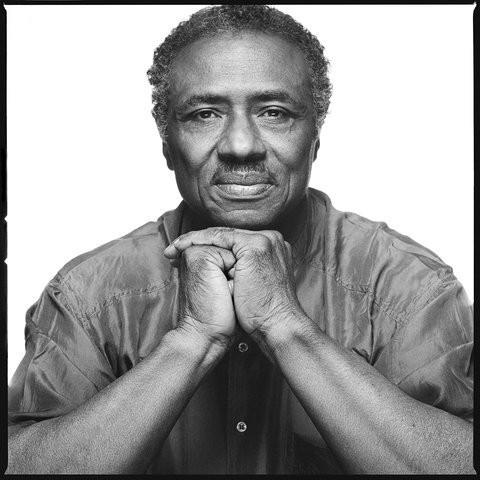

On March 14, Herman Bell learned that after 45 years behind bars, he would soon be released from prison. The 70-year-old former Black Panther was convicted in the 1971 shooting deaths of two New York police officers. Since 2004, he appeared before the state’s parole board seven times; each time, he was denied parole because of the nature of […]

On March 14, Herman Bell learned that after 45 years behind bars, he would soon be released from prison. The 70-year-old former Black Panther was convicted in the 1971 shooting deaths of two New York police officers. Since 2004, he appeared before the state’s parole board seven times; each time, he was denied parole because of the nature of his crime.

“There was nothing political about the act, as much as I thought at the time,” Bell said during his March 1 interview with the parole board. “It was murder and horribly wrong … It was horrible, something that I did, and feel great remorse for having done it.”

Though the parole board said that Bell’s crime “represents one of the most supreme assaults upon society,” two of the three commissioners nonetheless voted to grant Bell parole. In their vote, they cited his age, near-perfect prison record, college degrees, wide network of supporters and, perhaps most significantly, a letter of support from Waverly Jones Jr., the son of one of the slain officers. “The simple answer is it would bring joy and peace as we have already forgiven Herman Bell publicly,” Jones wrote in his letter to the board. “On the other hand, to deny him parole again would cause us pain as we are reminded of the painful episode each time he appears before the board.”

Bell’s parole comes after years of advocacy by formerly incarcerated people, their family members, and activists to change the state’s parole process. In 2011, an executive law directed parole commissioners to assess a defendant’s probability of recidivating rather than basing a decision on the nature of the crime. But in the following years, commissioners continued to hold 10-minute hearings before denying parole based on the defendant’s crime rather than their rehabilitative efforts in prison. That’s what happened to 70-year-old John MacKenzie in 2016 when he was denied parole during his 10th hearing; nine days later, he died by suicide, becoming a symbol of what critics called a “broken” parole system.

Advocates, including formerly incarcerated people who faced multiple parole denials, have pushed to change the composition of the parole board. Because commissioners are appointed by New York’s governor for six-year terms, advocates pressed Governor Andrew Cuomo not to reappoint commissioners with punitive track records; they also urged him to appoint commissioners with backgrounds outside of law enforcement. (Potential commissioners must have a college degree and five years’ experience in criminal justice, sociology, law, social work, or medicine.)

Advocates also pushed for changes to parole regulations, which now require the board to issue individualized reasons for denial.

In June, Cuomo chose not to reappoint three commissioners and appointed six new commissioners. Since then, says Steve Zeidman, director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the CUNY School of Law, parole hearings last longer than 10 minutes, commissioners’ questions have focused more on the defendant’s rehabilitation, and release rates have increased. In the following months, parole approvals rose from 24 percent to 37 percent. Two of these new commissioners served on Bell’s parole panel (though only one voted for his release).

Unsurprisingly, the decision to parole Bell has been blasted by the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), the NYPD commissioner, Cuomo, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Diane Piagentini, the widow of the other slain officer in the case. The PBA, along with several Republican lawmakers, are demanding that Cuomo fire the commissioners who approved Bell’s parole. Cuomo’s office has not returned a request for comment about these demands.

And even though the parole board voted to grant Bell his freedom, they can still rescind his parole should information emerge that commissioners had not been presented. That’s what happened to 58-year-old Shua’Aib A. Raheem who was sentenced to 25 years to life for a 1973 shooting in which one police officer was killed and two others wounded. In 2007, after Raheem was granted parole during his sixth hearing, the PBA fought to allow one of the injured officers and family members of the dead officer to submit victim impact statements. At a rescission hearing, the board rescinded his release. Raheem spent another three years in prison before being released on parole after another hearing in 2010.

Zeidman, however, cautions that such rescissions are rare; he told The Appeal that he can count the number of rescissions he’s seen in his 25-year career on one hand. Opponents can go to court to block Bell’s release, said Zeidman, but they are unlikely to find any relief. Indeed, in December 2017, the New York State Troopers’ Union filed a lawsuit to block the release of 74-year-old John Ruzas, who had been imprisoned since 1975 for fatally shooting a state trooper and had been denied parole 10 times. The judge, however, dismissed the case and Ruzas was released that month.

Still, the backlash about the parole board’s vote on Bell — “Law Enforcement Rages Over Cop Killer’s Parole” blared a New York Post headline the day of the decision — could influence its future decisions, particularly regarding defendants convicted of murder. “The intent behind the pressure is to make people afraid” of granting parole in controversial cases, Zeidman noted. He points to the fallout following the 2003 parole of Kathy Boudin, a former Weather Underground member who participated in a 1981 robbery of a Brink’s truck that left a security guard and two police officers dead. The two commissioners who granted her freedom were not reappointed.

“It sends a message that, even if you follow the law, you’ll be fired if it’s an unpopular decision,” Bell’s attorney Bob Boyle told The Appeal.

Against the backdrop of such repercussions, “what the parole board did [in granting Bell parole] was courageous,” said criminal defense attorney Zeidman. “Most people would say that they just followed the law, and that’s true. But they haven’t been following the law before. And they knew that there was going to be this kind of backlash and this kind of attack.”

Waverly Jones Jr. wrote in a statement to the media that he, too, is concerned by the resistance parole commissioners have faced for their decisions. “Particularly upsetting is the attack on the Parole Commissioners who made the decision to release him,” Jones wrote. “The fact is that Mr. Bell has taken responsibility for his actions, has expressed genuine remorse, is 70 years-old,and has been in prison for 45 years. In these times of increased hate, we need more compassion and forgiveness.”

“There’s been a sea change,” reflected Zeidman. “Whether this [backlash] has the power to stop this in its tracks is what people are afraid of.”