California Prison Guard Union Responsible for ‘Bullseye’ Ad Donates $1 Million to Jackie Lacey’s Re-election Campaign

Late-stage donations to the Los Angeles DA race increase concerns about the influence of law enforcement money on politics.

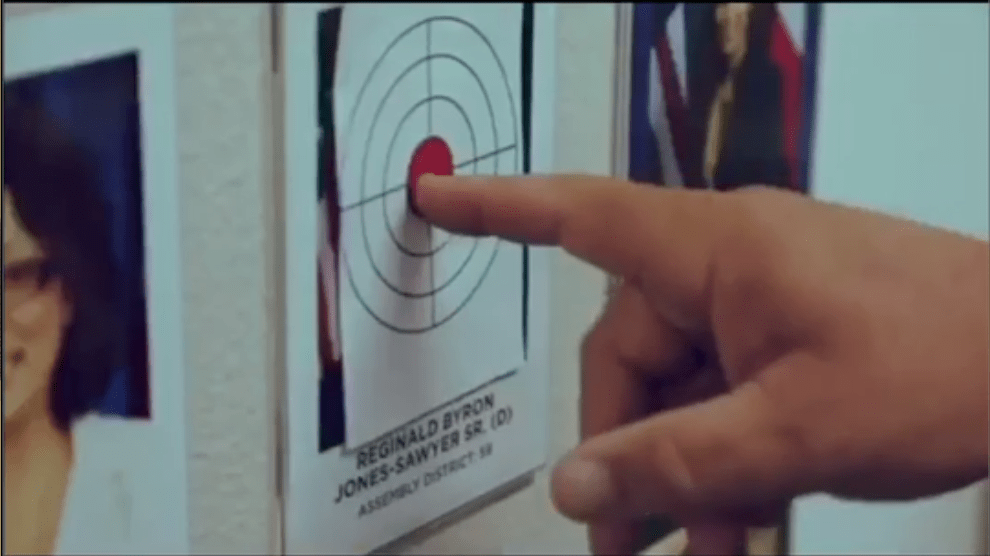

On Sept. 16, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), a union that represents prison guards, posted an ad online depicting a bullseye target placed over a photo of Black state Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer—a move that many lawmakers interpreted as a racist threat.

The bullseye over Jones-Sawyer’s face is hardly the ad’s only provocative image. The two and a half minute video also features scenes of a man in a hoodie pressing a knife against a terrified white woman’s face, and a white sheriff’s deputy shackling a Black person in an orange jumpsuit. “On this date, we further our commitment to the legislators who aren’t afraid to stand with law enforcement,” the narrator intones. “CCPOA is prepared to take the lead and speak the loudest.”

After pushback by lawmakers and advocates, CCPOA quickly took the ad down, but it appears the union wasn’t bluffing. On Sept. 11 and 17, the CCPOA quietly donated a total of $1 million to two law enforcement PACs supporting controversial Los Angeles incumbent District Attorney Jackie Lacey, according to campaign filings. These late-stage contributions have heightened the stakes in an already close and highly scrutinized contest—and furthered some experts’ and activists’ suspicion that law enforcement is trying to buy the race.

In Los Angeles, police contributions to Democratic campaigns are not unheard of. But these enormous, late-breaking sums are still significant. The influx of cash from the CCPOA follows a Sept. 10 $200,000 donation to a PAC supporting Lacey from the Los Angeles Professional Peace Officers Association, a union representing the sheriff’s department, the coroner’s office, and the DA’s office.

Lacey is the clear favorite of police, sheriff, and prison guard unions: During the primary, the overwhelming majority of her donations came from law enforcement, and the Los Angeles Police Protective League alone donated $1 million to a PAC opposing her challenger, George Gascón.

“Jackie Lacey has demonstrated that she is incapable of policing the police, and these unions are going to spend millions to make sure that does not change,” said Gascón in a press release Wednesday night in response to news of the CCPOA’s two recent donations. Neither Lacey nor the CCPOA responded to The Appeal’s requests for comment.

Lacey, a Black woman from South LA, has drawn the ire of criminal justice reform advocates for aggressively pursuing the death penalty—exclusively against people of color—and declining to prosecute cops who kill civilians while on duty.

Such last-minute contributions suggest that the race may be tipping in favor of Gascón, San Francisco’s former district attorney and a former assistant chief of the LAPD. Though he has an imperfect progressive record, the LA activist network has held up Gascón as the necessary alternative to Lacey.

Black Lives Matter Los Angeles has been organizing “Jackie Lacey Must Go’” protests at the Hall of Justice, where the DA’s office is located, every Wednesday since October 2017. Sheila Hines-Brim, whose niece, Wakiesha Wilson, died in sheriff custody in 2016, has attended many of the weekly protests. Yesterday, she led the crowd in chants calling for Lacey’s ouster because of her failure to hold police accountable for civilian killings.

Hines-Brim called the donations from the CCPOA “ridiculous.” “These officers have declared war on Black folks, and Jackie Lacey has not prosecuted them,” she told The Appeal. “It’s sad that she’s even accepting the money.”

“CCPOA is doing what it’s supposed to do, which is to support the interests of its members,” said John Rappaport, a University of Chicago law professor who specializes in criminal procedure and the criminal justice system. Rappaport told The Appeal that he sees such donations as both “unsurprising” and “deeply concerning”—“especially given current public sentiment, when it’s coming from a union whose interests point toward more incarceration rather than less.”

Amid worries about the influence that law enforcement money can buy, some prosecutors have eschewed it entirely. Cristine Soto DeBerry is the executive director of the nascent Prosecutors Alliance of California, which was formed after continued resistance to reform by police and prosecutors, even after George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis in May. “Contributions from police unions create so much doubt in the public’s eye as to whether a prosecutor’s decision is impartial and driven by the facts and the law—or whether they are payback for the support,” she told The Appeal. “It’s a conflict that contributes to the ever-expanding gulf of distrust between law enforcement and the communities we serve.”

Her group doesn’t just want prosecutors to voluntarily forego law enforcement cash. In June, Soto DeBerry and a number of other influential prosecutors appealed to the California State Bar, asking the organization to prohibit DAs from taking police union contributions.

Jackie Lacey has opposed their efforts.