Black Men Disproportionately Represented On Sex Offender Registries

Even though it’s unlikely that they commit sexual assault at higher rates than other ethnic or racial groups, nearly one of every 100 Black men is on a sex offender registry, a rate double that of white men.

In 1999, Kevin,* a Black 19-year-old, was partying at the East Texas home of a friend who had a 12-year-old sister. Kevin remembered that he watched TV with his friend’s sister and admitted that at one point he touched her breast. When she told her mother about the incident, Kevin was charged with felony indecency with a child. The district attorney’s office offered Kevin deferred adjudication—meaning that he would have no criminal record if he successfully completed 10 years of probation—and he took the deal.

But Kevin didn’t realize he would be placed on Texas’s sex offender registry. Like other states, it is public in accordance with the federal 2006 Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act named for 6-year-old Walsh, who was kidnapped and found murdered in 1981. Kevin didn’t know that the registry required that his name, photo, and address be published. Nor did he know that he would be put on the registry for life. Though he completed his probation eight years ago and has no other arrests on his record, he remains on the registry nearly 20 years later.

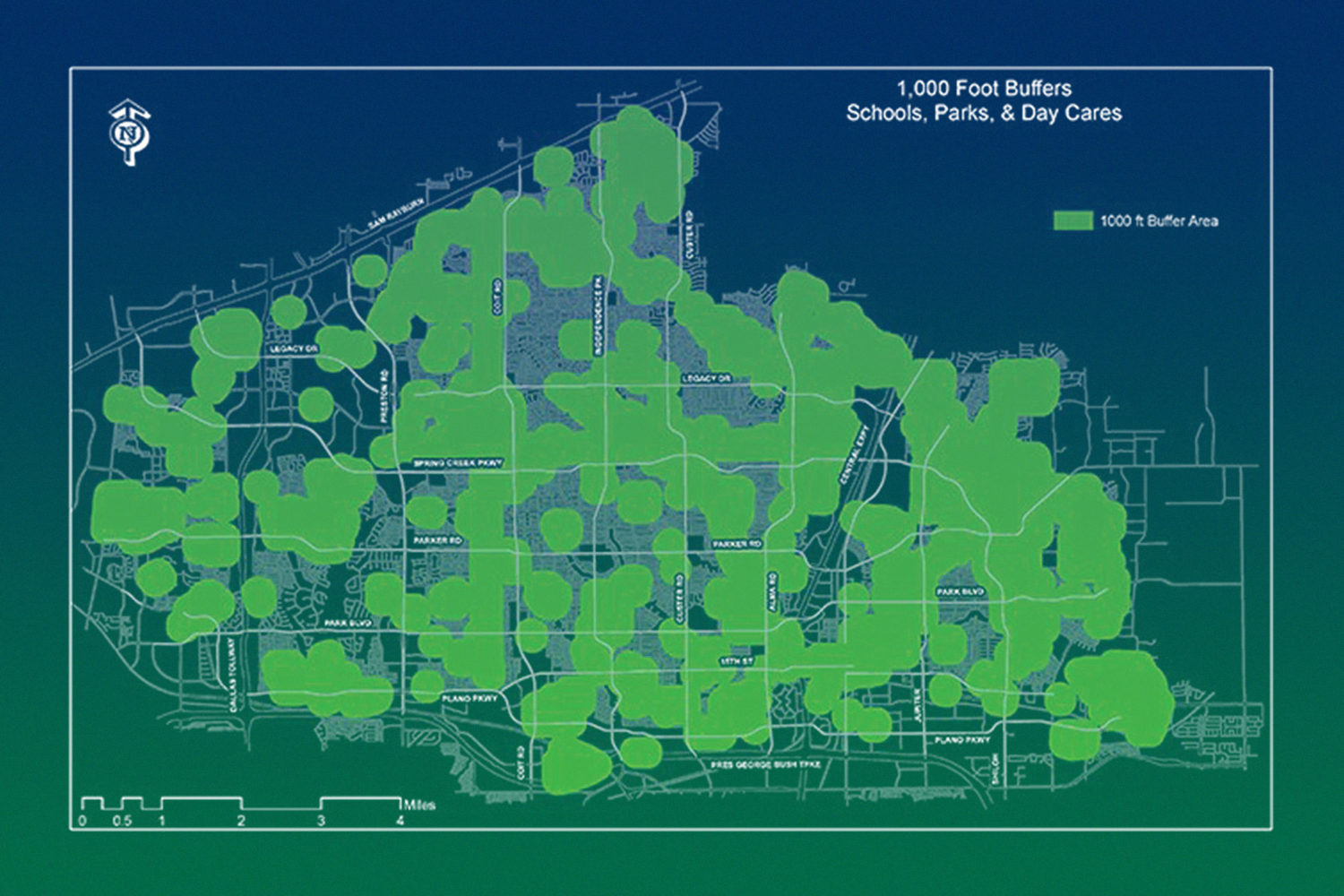

Kevin also didn’t realize that he would be subjected to draconian laws about where sex offenders can live or work, such as the one in the city he lived in that bans sex offenders from living less than 1,000 feet from any place where children congregate, including schools, daycare centers, playgrounds, youth centers, public swimming pools, and video arcades. Many other states and localities have similar laws. In Georgia, a law that its General Assembly enacted in 2006 made it illegal and punishable by 10 to 30 years in prison for people on the sex offender registry to live or work within 1,000 feet of a school or other place where children gather. The law makes it virtually impossible for registrants to live anywhere in Georgia. In Miami Beach, an ordinance was passed in 2005 banning people on sex offender registries from living within 2,500 feet of a school, legislation that led in part to a massive homeless encampment near Miami International Airport.

But the requirements of sex offender registries have not made communities safer. According to a 2014 study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence, sex offender recidivism during the first five years after release from prison ranges from less than 3 percent for the lowest-risk offenders to 22 percent for those at highest risk. In contrast, according to Department of Justice data, 33 percent of violent offenders commit another violent offense within five years, and 51 percent of drug offenders break another drug law.

Meanwhile, sex offender researchers have found that the longer a sex offender goes without re-offending, the less likely the person is to do so. A 2018 study in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law has found that the chance of a sex offender committing a new sex crime after 15 years is 2 percent. That’s roughly the same rate as for people convicted of other crimes, who then go out and commit a sex crime. And there’s no evidence that sex offenses and recidivism are reduced by registries. Instead, they appear to be a product of moral panic and the trend to increase criminalization, surveillance and shaming.

Black people like Kevin are disproportionately represented on the registry. A 2004 Iowa Law Review study of registries in 17 states found that Black people are more than 1.9 times more likely to be on registries than white people. In 2010, University of Washington Tacoma criminologist Alissa Ackerman and her colleagues examined records for over 445,000 people on registries in 49 states, Washington, D.C., and Guam. They found that Black people were more than twice as likely than whites to be on sex offender registries.

Today, about 900,000 people are on public sex offender registries with about one of every 100 Black men on a registry, a rate double that of white men. Despite the disparate racial impacts of the registry and that they are ineffective in increasing public safety, “people like registries” says Valdosta State University criminologist Bobbie Ticknor. “They like knowing they can hop on their phone and find an offender’s address.” In July, Ticknor and her colleague Jessica Warner at Miami University Regionals, in Ohio, published a study in the Criminal Justice Policy Review suggesting that Black men are more than twice as likely as whites to be overclassified on sex offender registries. Registries generally classify offenders as low, moderate, and high risk. States assign varying minimum times that a person in each classification must stay registered: from 15 years to life. Ticknor and Warner’s study also found that statistically, Blacks must re-register more frequently than whites and spend more time on the registry.

Black men are also twice as likely as whites to be arrested for sex offenses, and three times more likely to be accused of forcible rape. But it’s unlikely that they commit sexual assault at higher rates than other ethnic or racial groups. The overrepresentation of Black men in sexual assault cases may be due in part to the fact that they are disproportionately wrongfully accused. According to the University of California at Irvine’s National Registry of Exonerations, 59 percent of sexual assault exonerees are Black, which is four and a half times their proportion in the general population. Black sexuality and racism have long been intertwined in the criminal justice system, such as in the cases of Emmett Till and the Scottsboro Boys. Indeed, many people on the registry were arrested and convicted decades ago, when racism in charging and jury selection were much more pervasive in the criminal justice system. One of them is a Black man in Alabama convicted of rape in 1955. He is still on the registry at age 81—for an offense he committed at 19.

Back in Texas, Kevin’s listing on the state registry has resulted in termination from a job, and the sheriff’s department once ordered him out of a home he rented. His employment is largely confined to janitorial work. Kevin lives in a relative’s house in the countryside. It’s the only place he’s found that complies with his community’s residence restrictions for people like him.

*The Appeal agreed to identify Kevin only by his first name because of the profound stigma, shame, and danger from vigilantism associated with sex offender registries.