Advocates Fight Florida Law Used to Detain Thousands of Kids in Crisis

A law originally set up to provide humane treatment to mentally ill people in crisis has became a terrifying dragnet for kids, with Black children under 10 greatly overrepresented.

This story was reported and produced by MindSite News, a nonprofit news site focused exclusively on mental health reporting, and is republished with permission. You can sign up for the MindSite News Daily newsletter here.

The story has been updated to note efforts to get comment from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in the 16th paragraph and to specify the ages of children held under the Baker Act in the 33rd.

The 9-year-old Florida boy was having a bad day. Two days earlier, his grandmother and legal guardian had notified Lantana Elementary School in Palm Beach County that there had been a death in the family and that he might be struggling as a result. The boy, identified as “D.P.” in legal papers, had also been diagnosed with autism and attended school in a classroom with other children with autism and intellectual disabilities.

His grandmother’s warning went unheeded. When his teacher declined to let him use a computer, D.P. became upset and began throwing stuffed animals around the room. When things like this had happened before, his teachers let him take a walk or sit by himself for a while. Not this time. Two staff members restrained D.P. face down on the floor and called a school district police officer, who handcuffed the boy, put him in the back of a police car, and took him to the hospital for an involuntary mental health exam. He called the boy’s grandmother to let her know what he was doing, but he did not ask for her consent.

Seizing children and adults and placing them on involuntary mental health holds happens so frequently in Florida it has become a verb: Baker Acted—a reference to a law passed in 1971 and known officially as the Florida Mental Health Act. Like many state laws of that era, it was intended to reduce some of the horrors of asylum care while allowing for severely mentally ill patients who might be a danger to themselves or others to be evaluated and committed for involuntary treatment, even if they didn’t consent.

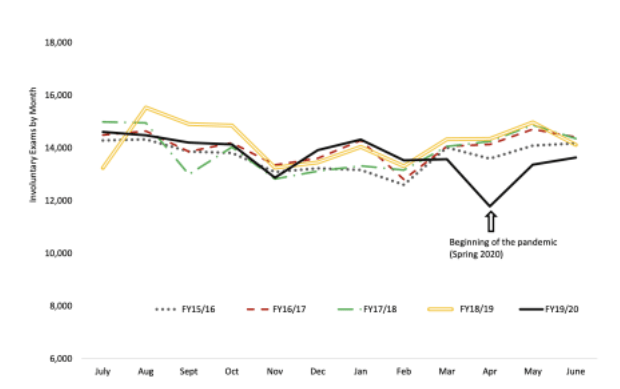

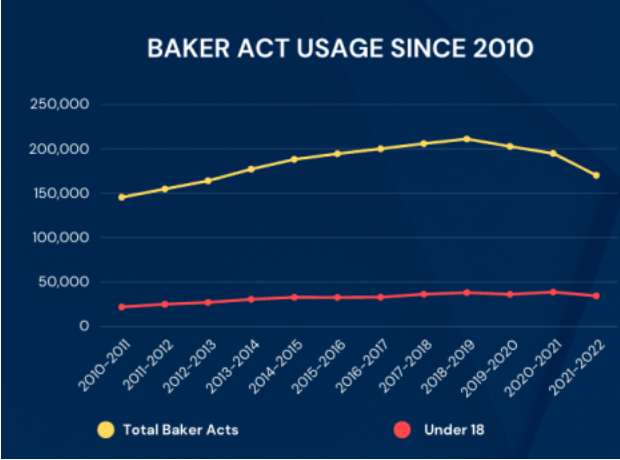

After years of steady increase, the number of Baker Act holds reached a peak in 2019–20 when Florida residents were subjected to more than 200,000 mental health holds—and then declined for the first time as the COVID-19 pandemic began.

The law as originally passed expressed the intent that forced examination and treatment be performed with “the least restrictive means of intervention” and that “individual dignity and human rights be guaranteed.” Instead, it has become a dragnet of sorts that brings hundreds of thousands of adults and children to hospitals and mental health facilities where they can be held for up to three days—five if the days fall on a weekend.

Indeed, over the past 10 years, adults in Florida have been seized and subjected to 1.5 million forced psychiatric exams, and children—some as young as 5—to 335,000 such forcible exams under the Baker Act. Some “unscrupulous facilities” hold them longer to collect more insurance money, according to a 2021 report from the Southern Poverty Law Center. It cited one Tampa area facility that has held adults and children an average of more than eight days by filing petitions for a longer stay and then dropping the petitions before they could be heard.

Researchers who study involuntary commitment say Florida is an outlier. A 2020 study showed the state had the highest rate of emergency mental health detentions among 25 states with publicly available data. In the study, emergency detentions ranged from 29 per 100,000 people in Connecticut to 966 in Florida. The study also said Florida involuntarily examines and commits children “at a rate much higher than any other state in the country,” according to a 2023 report from the University of Florida Levin College of Law; indeed, more than 34,000 kids under 18 were seized and held in psychiatric wards in the fiscal year 2021–2022. The report noted that in many cases children are harmed by the process—and their parents are stuck with thousands of dollars of bills from treatment they never sought or authorized.

Due partly to the COVID-19 pandemic and partly to protests and legal actions mounted by advocates, this trend’s upward arc seems finally to be abating over the last few years—but only for adults. An annual report recently released by the state shows that for the year ending June 30, 2022, the total number of people held under the Act declined by almost 13 percent, while the number of children seized remained essentially the same and now constitutes 20 percent of all holds. Among children who are Baker Acted, Black children 10 and under are disproportionately represented.

Advocates say the seizures have traumatized children and adults in Florida, especially kids with disabilities who may not even understand what is happening. Some of the children believe they are heading to jail because of the handcuffs and uniformed police involvement.

“They’re socially regressing. They’re having nightmares. They’ll have been potty trained and now they’re bedwetting,” said Caitlyn Clibbon, a public policy analyst for Disability Rights Florida. “There are kids who are just absolutely terrified to go to school, where before they enjoyed school.”

“It can be incredibly traumatic even for adults and that’s just magnified when you’re talking about kids and their still-developing brains,” Clibbon added.

D.P.’s experience with the Baker Act has had a lasting impact. After that day almost five years ago, he became more aggressive and easily upset, developing a fear of police and school staff and a need for ongoing therapy, according to a 2021 lawsuit filed by Disability Rights Florida, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and other legal groups against the School District of Palm Beach County. At the time of the lawsuit, the district was initiating nearly 300 Baker Act holds a year.

According to the lawsuit, children taken under the Baker Act are frequently handcuffed, placed in the back of a police car and driven to a hospital. Some are held in the hospital for days before they are evaluated and released. The students in the lawsuit had a range of disabilities, including autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder, that were all known to school officials—even though the Baker Act specifically prohibits its use for developmental disabilities such as autism. The law also makes clear that “antisocial behavior” is not a mental illness, and the Baker Act was not intended to punish children—disabled or otherwise—who misbehave in class.

Last month, the school district agreed to pay $440,000 to the families of D.P. and three other children with disabilities—and, more importantly, to implement policy changes, including a mandate that mental health professionals rather than police approve any forced examinations.

The district created a multidisciplinary team to assess the need for an evaluation. It also agreed to review Baker Act holds on a monthly basis in schools that exceed two per month and to conduct training when necessary, according to Keith Oswald, chief of equity and wellness for the school district.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and his communications office did not respond to calls and emails seeking comment on the racial disparities and high levels of police involvement in the placing of Baker Act holds.

Advocates were generally pleased with the settlement and some policy changes made by the district, which contributed to an 80 percent drop in Baker Act holds there since the lawsuit was filed in 2021, said Sam Boyd, an attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center. But he and his colleagues are seeking additional changes to require parental consent for non-emergency holds, bar the usage of handcuffs on students who pose no threat, and require transportation in vehicles other than a marked police car.

“The district still has more to do” to stop such abuses, said Boyd. And so do many other districts around the state, according to the SPLC.

Now attention is likely to shift to them—and to changing statewide policy on how the Baker Act is used on children. A 2021 SPLC study, “Costly and Cruel,” explored the frequent use of the Baker Act as a behavioral management tool—to punish simple misbehavior—and found excessive use against children with disabilities in school districts in Jacksonville, Tampa, Broward County, Pasco County, and Orange County.

In 2022, two bills were introduced in the state legislature by Sen. Bobby Powell Jr. and Rep. Fentrice Driskell, both Democrats, to increase parental involvement when children face the possibility of being Baker Acted. The bills eventually stalled.

Lots of school cops, few counselors or psychologists

In Florida, the Baker Act is so widely used and such a part of residents’ consciousness that conversations about it are common.

At local bars, people share stories of husbands or wives Baker Acted after an argument. Others post about their traumatic Baker Act experiences on Reddit. In a chat with a visiting journalist, a hotel worker shared her own story of being Baker Acted, which occurred several years ago when she was in high school. Students at the school feared they would be held at a psychiatric ward under the act if they experimented with marijuana or other drugs, she said, adding that her own “treatment” was abysmal.

“We see an excessively high use of involuntary commitment in Florida — higher than in any other state that we have data for,” said Nev Jones, a psychologist and assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh who researches community-engaged mental health services. “Part of why I think that happens here is a really, really heavy reliance on police involvement.”

The large number of school police officers is one factor driving Florida’s high rate of involuntary holds on kids. Three years ago, the ACLU of Florida reported that the 3,650 police officers working in Florida schools exceeded the number of school nurses (2,286) and was more than double the number of school social workers (1,414) and psychologists (1,452).

Florida has a serious shortage of those professionals. During the 2020–2021 school year, for example, Florida had one school psychologist for every 1,828 students, far below the recommended level of one psychologist per 500 students and the national average of 1-to-1,162, according to Department of Education data. Similarly, the counselor-to-student ratio of 1-to-434 was far below the recommended level of 1-to-250.

Perhaps if an Orange County school counselor had been available, Shawn M., 10, who has autism spectrum disorder, would not have been remanded to a psychiatric facility in 2018 when he had a strong reaction to a game similar to “cooties” that he and his fourth grade classmates were playing. In a scenario recounted in an SCLC report, his teacher called a sheriff, who took the terrified youngster to a psychiatric facility.

“To this day, Shawn is still afraid, haunted by the day in 2018 that he was taken from his school by a police officer, caged in the back of a police car, driven away from his distraught father, and held overnight without contact with his family in a psychiatric ward with older children—all because he expressed to a teacher some distress over losing a playground game…[He] frequently talks about not wanting to ‘go to jail’ again—an indistinguishable experience in his mind from the experience of being Baker Acted,” the report noted.

Not surprisingly, the experience of being locked in a psych ward is often traumatic to both children and adults. One University of Florida study “found that 54% of individuals experienced being around frightening or violent patients as a harmful experience, 59% were subject to seclusions, 34% experienced being held in restraints, 29% faced forceful takedowns, 60% were handcuffed during transport, and 20% were threatened with medication as a form of punishment.”

From July 2021 to June 2022, the most recent period for which data is available, Floridians were subjected to 170,048 involuntary mental health holds under the Act. Law enforcement officers initiated 53 percent of these holds—a 1 percent increase over the previous year, according to an annual report released by the Baker Act Reporting Center at the University of South Florida. In the 2021–2022 report, more than 20 percent of Baker Act holds were on children—with some striking gender gaps. In children aged 5 to 10, two-thirds were boys, while among adolescents from 11 to 17, more than 63 percent were girls.

And many children were seized under the Act repeatedly—some as many as 11 times in a year. Almost half—45 percent—of all Baker Act holds were placed on just 21 percent of the children.

“Unnecessary use of the Baker Act against children has become tragically routine,” according to the 2021 SPLC report. “The high rate of repeat Baker Acts of the same children…also suggests that involuntary psychiatric holds fail to appropriately and accurately treat the underlying conditions that lead to these children being examined in the first place. The very act of Baker Acting a child traumatizes them, and, for some, puts them at greater risk of harming themselves or others.”

The experience can also cause kids to miss school time and lead to separation anxiety, depression, and emotional withdrawal, according to the SCLC, as well as school transfers and losing ground academically. Children also may become fearful, making it less likely they’ll seek counseling, and develop a distrust of teachers, medical professionals, police officers, and adults in general.

The report also showed racial disparities. Black children make up just 20 percent of pre-K to 5th graders in Florida public schools, but accounted for 32 percent of those held under the Baker Act. In the Palm Beach schools, 40 of 59 children under the age of eight Baker Acted from 2016 to 2020 were Black.

These numbers are in part a reflection of how public officials continue to paint Black people – even children—as dangerous, said Jones, the University of Pittsburgh researcher. Seclusion and restraint are also used more commonly on Black patients in psychiatric facilities, Jones said.

In 2021, Jones conducted a study that looked at the experiences of young people ages 16 to 27 held under the Baker Act. She found that police involvement made them feel they were being scrutinized and treated like criminals, even in their most distressed and vulnerable moments.

This nightmarish scenario is one advocates want to prevent. With a victory in Palm Beach under their belt, they will now turn their attention to other districts across Florida and try to force similar changes.

“The problem is statewide,” said Clibbon from Disability Rights Florida. “Now we hope to take some of the findings and policy changes from Palm Beach and advocate for improvement across the state.”

Because the stakes are high.

“Being handcuffed, shoved in the back of a police car, and potentially threatened—that is really harmful psychologically even if there’s no death or physical injury,” said Jones. “It sets youth on a path of really good reasons to deeply distrust ‘helping systems.’”