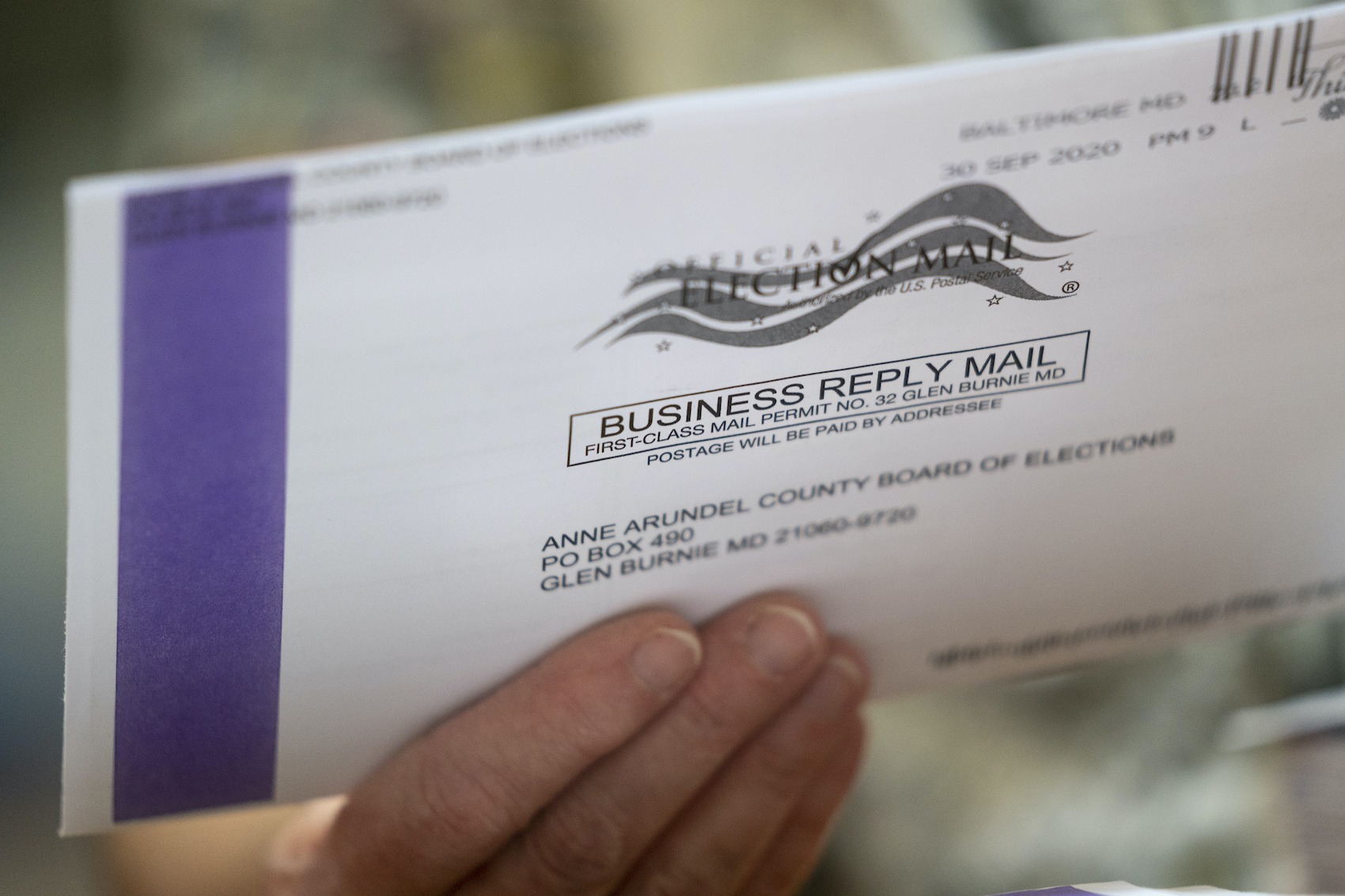

As More States Turn To Mail-In Voting, Problems Pop Up Across Country

Last week’s problems in New York were part of a widespread series of issues, both systemic and targeted, that are only now becoming fully apparent, activists say.

When Celia Rodriguez headed to the post office on Sept. 28, she brought with her two stamped envelopes containing her and her daughter’s mail-in ballots for the November election.

“We wanted to get our ballots in,” said Rodriguez, who lives in Manhattan. “You know, there’s all this talk about the ballots not getting where they need to be and not counting.”

So the two filled out the ballots and put a stamp on the corner of each envelope. But upon arriving at the post office, Rodriguez found that the postage for mailing her ballot was 15 cents short. There was no indication on the envelope that extra postage was necessary.

It wasn’t an issue for Rodriguez, a retired schoolteacher with a master’s in early childhood education. In the end, 30 cents was all it took total to get the two ballots mailed. But the experience shook her enough that she alerted her local representative, New York State Assembly member Yuh-Line Niou, to the situation.

“Why don’t we know about that?” asked Rodriguez, referring to the need for additional postage. “That’s important information.”

Complaints to Niou over postage were not limited to the Rodriguez family that Monday, and as the day dragged on, it became clear that problems were not unique to her district. In addition to confusing postage requirements, ballots across the city were being delivered to the wrong address.

“I’m just very worried that there are different things for different folks,” Niou said. “I think that people are really not able to simply trust the mail-in ballots which is terrible because, you know, other states have had really good mail-in ballot systems. We’re really behind, and not being diligent.”

Problems with early and mail-in voting are popping up nationwide, in important states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Virginia. Although the post office has promised to deliver ballots irrespective of postage, as the agency told Reuters in August, the persistence of issues around the vote are causing headaches and concern for people like Rodriguez.

One post office employee and union steward in the Midwest told The Appeal that the blame for vote-by-mail irregularities largely lies with boards of elections—not the postal service. If postage is an issue, the employee said, voters need to recognize what that really represents.

“The ballots are quite unwieldy so the automated system might try and claim you need postage,” said the employee, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity out of concerns for his employment. “But as far as voting, that would be a poll tax.”

According to Spread the Vote executive director Kat Calvin, the real issues with vote-by-mail are really just beginning because ballots are starting to be mailed out. “It’s probably only going to get worse,” Calvin said.

While New York is seeing an outsize number of problems, other states are sure to see complications as well.

“We still have states changing laws every day,” said Calvin. “There’s dozens of lawsuits in every state. So I think people are just feeling confused and worried and like the whole system is hopeless.”

Some Republican state lawmakers, like Texas Governor Greg Abbott, have taken deliberate steps that are making it more difficult for people to vote. A rule change that Abbott put into effect on Oct. 2 limits the number of drop-off places for absentee ballots to one per county. Critics of the move say it will almost certainly have a deleterious effect on voting in the state, where some counties are thousands of square miles wide.

In Iowa, over 100,000 ballot requests are in limbo after the Trump campaign and Republican Party groups sought to invalidate request forms with pre-filled voter information. Voters in Indiana are reporting problems with improperly initialed ballots. Narrow limitations on applying for absentee voting are creating issues for Mississippi voters. And in Philadelphia, voters waited for hours in lines last week at one of the city’s first-to-open one-stop shops for registering, filling out, and casting absentee ballots. The delays threw the state’s ability to handle the election into question.

Sarah Brannon, managing attorney of the ACLU Voting Rights Project, is focused on Pennsylvania this election cycle. She told The Appeal that concerns over Philadelphia’s elections were a bit overblown, in her view. She said the state is doing its best to ensure that it abides by Act 77, a 2019 law passed by a broad bipartisan state coalition that allows people to vote by mail for any reason for up to 50 days before Election Day. The law is now the centerpiece of efforts to address COVID-19’s effect on the ballot.

“I think it’s part of something you’re going to see in other places too,” said Brannon. “They’re implementing processes that they haven’t had before or haven’t used before in such large volume for people who need them because of COVID—and that’s contributing to things like unexpected long lines at the city hall in Pennsylvania.”

Brannon told The Appeal that vote-by-mail rules and regulations vary widely throughout the country, and even within states. Further, many boards of elections are not set up to handle the operational challenges from a high volume of voters choosing to send their ballots in by mail.

“In most places in the United States—not all of them, because there are some states that have been voting by mail for many years without trouble or issue or incident—but in many places in the country, vote by mail has not historically been the most common way to vote,” Brannon said.

Brannon said her advice to voters is, first, that they call their local elected officials and ask if postage is necessary and make sure to follow the directions on the ballot envelope itself.

“Many people will put their ballots in the mail without worrying about the postage,” said Brannon.

Although there’s a concerted, nationwide effort to get postage payment covered, it’s still unclear if that will come in time to address the November election, Brannon said. As for the technology that the post office uses to handle ballots, it’s largely automated and shouldn’t be an issue, she said.

Even once ballots are turned in, however, there are still concerns over whether they will be accepted. Issues around “naked ballots”—votes sent into voting centers without a necessary second envelope inside the mailing envelope—and other technical problems could lead to widespread invalidation.

Noting that half a million ballots were thrown out during the primaries, Spread the Vote’s Calvin pointed to the increased turnout and varied rules in the general election and warned that the likelihood is high that even more votes will be contested and ultimately rejected.

“I don’t think that anybody is going to solve these problems in the next few weeks—we have, what, four weeks until the election?—that they haven’t solved in the last seven months,” Calvin said.