Chesa Boudin Looms Over the Race for the Oakland Area’s Next Prosecutor

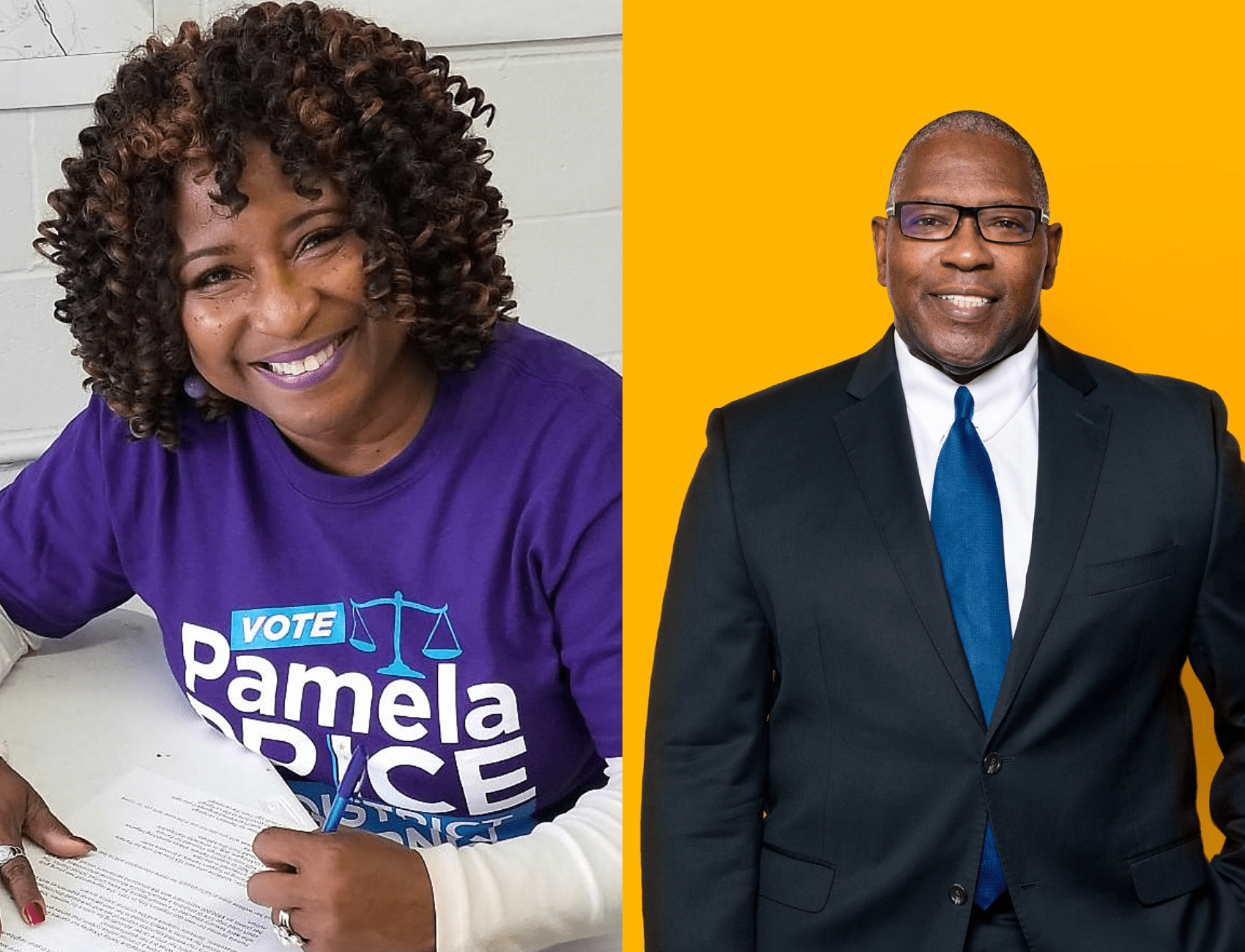

Pamela Price is running a progressive campaign to change the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office in California. She’s winning. But her opponent, longtime prosecutor Terry Wiley, is trying to paint her as the next Chesa Boudin to score votes.

On June 7, Pamela Price, a career civil rights attorney who has been living and working in and around Alameda County, California, since 1978, received the highest percentage of votes in the primary race for county District Attorney. But because Price was unable to secure a majority of the vote, only earning 43 percent, she will face distant runner-up Terry Wiley in a runoff. The race will determine the next prosecutor for the more than 1.6 million people who live in Oakland, Berkeley, and their surrounding suburbs.

Price’s civil rights career has spanned decades. In 1977, while an undergraduate at Yale University, Price joined the legal case Alexander v. Yale, which would ultimately become a landmark case establishing that sexual harassment in education constitutes illegal sex discrimination. Since then, Price has focused on cases of sexual and racial discrimination and opened a private practice in 1991. In 2018, Price ran for DA as a progressive challenger to incumbent Nancy O’Malley, but lost after police unions spent heavily to support O’Malley’s campaign.

Terry Wiley, meanwhile, is currently the third highest-ranking member of the Alameda County District Attorney’s office and has worked in the office for the past 32 years. Most notably, he prosecuted the historic Oakland Riders Case, in which four Oakland Police officers were accused of kidnapping, planting evidence, acts of violence, and other serious misconduct, but were either acquitted or had their charges dropped. (One of the officers fled and is still wanted by the FBI.) As head of the felony trial team, Wiley says he cut the rate of children in custody by two-thirds. He was also the first African American to head the office’s recruitment and development division and is campaigning on having increased diversity within the prosecutor’s office.

This election is historic for many reasons. For one, both candidates are African American, and the winner will be the first African American District Attorney the county has ever had. It is also the first time in 13 years that the prior DA did not appoint the next DA, thus giving that incumbent name-recognition during the next election cycle. Former DA Jack Meehan, who held the job from 1981 to 1994, was succeeded by Tom Orloff, his former assistant DA, who ran unopposed. Orloff served from 1994 to 2009, retired before the end of his term, and appointed current DA Nancy O’Malley, who has served since 2009.

Both candidates claim to want to change the culture in the office: Wiley has said he will focus on the 2,000 repeat offenders who commit the majority of crimes in Alameda County, increase the number of people referred to drug treatment and mental health care programs, expand job training and union internship programs in the community, and focus on anti-Asian violence, domestic violence, crimes against children and hate crimes. But Wiley has also gained support from many establishment voices, such as Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and the California Police Chiefs Association. To combat police misconduct, he says he would push for more police training to “root out bias.”

While it may seem then that Wiley has the upper hand, Price, who crushed Wiley in the primary race, has support from local civil-rights leaders Angela Davis, Elaine Brown, and Susan Burton. (Rapper and actor Common has also endorsed her.) Price’s platform sits to Wiley’s left. She says, among other measures, that she will release significantly more reports on how her office handles cases, increase funding to her office’s Conviction Integrity Unit, reduce reliance on “ineffective prosecutions” to curb gun violence, stop charging children under 18 as adults, keep Alameda County a “sanctuary” community for immigrants, prioritize holding police and prosecutors accountable for misconduct, increase funding for reentry strategies, and invest in public health and social services. She has said that, if elected, she will not seek the death penalty against any person. However, in 2018, Price said she would not prosecute any misdemeanor cases if elected, but later reversed her position during that election cycle.

The role of the district attorney is to prosecute criminal violations of state law and county ordinances. Therefore, the DA determines the outcome of criminal trials for one of the most populous counties in America. While outgoing DA O’Malley has not appointed a successor in the race, one of the two candidates—Wiley—appears far more likely to carry on the tough-on-crime traditions of what has historically been a scandal-plagued DA’s office.

Just across the bridge in San Francisco, progressive prosecutor and former San Francisco County DA Chesa Boudin was recalled in June after a conservative-backed smear campaign just two years into his tenure. Despite the bad-faith attacks on Boudin’s record, Wiley has used his recall as a battle cry to Alameda County voters as he campaigns for public safety, warning voters to beware that Price will implement Boudin’s prosecutorial strategies and subsequently cause an increase in violence and crime should she win.

In an interview with The Appeal, Wiley said he felt Boudin’s policies “left victims behind” and would be dangerous in higher-crime areas, such as parts of Oakland.

“[Price] would be Chesa Boudin on steroids in Alameda County,” Wiley said. “And I say that because when you look at the serious and violent crimes, it is much more serious and much more violent and it is in much higher volume in Alameda County. Therefore the cost to the citizens of Alameda County is going to have a much greater impact.”

Price’s campaign did not respond to requests for comment.

But Alameda County is not San Francisco. Its voters have a different ideology, and its population is more diverse, with about double the percentage of Black residents, and a median household income of about $15,000 less. And despite the fact that he has hit Price and Boudin for being “soft on crime,” the county’s most populated city, Oakland, reached more than 100 homicides for the first time in a decade in 2021, while Wiley was a prominent leader in the DA’s office.

What happened across the bridge is not the only point of contention in the race. The health and safety troubles at Alameda County’s Santa Rita Jail, the fifth-largest jail in the country, remain a heavily debated topic. Since 2014, at least 58 people have died while in custody there, with seven of those deaths occurring in 2021. The Alameda County Sheriff’s Office has been the subject of civil-rights lawsuits over the facility, and in 2022 a federal judge placed the jail under external oversight for the next six years.

Price has vowed to launch a criminal investigation into the jail and stated in an interview with KPFA’s Jesse Strauss that “unfortunately, for decades, our sheriff, our district attorneys have just been … partners essentially in allowing lawless and criminal behavior to take place at that county jail facility.” She continued, “Where you have people dying in jail, that’s beyond mismanagement, that becomes criminal activity that has to be investigated by the district attorney’s office.”

In September, 47 Alameda County Sheriff’s Office (ACSO) deputies were stripped of their guns and their ability to make arrests after an audit revealed they didn’t pass psychiatric evaluations. Of the 47, 30 worked at Santa Rita Jail. The audit of the department was only triggered after Deputy Devin Williams Jr. was accused of committing a double homicide in Dublin, California. Williams had failed his law enforcement psychological exam. Had the murder not occurred, these officers may have still been managing Santa Rita Jail and patrolling the county.

In an interview with The Appeal, Wiley said he feels “any death that occurs inside a locked facility like Santa Rita Jail in Alameda County is unacceptable” and that “there is a systemic problem within the sheriff’s department” because of the number of people who were allowed to graduate and become deputy sheriffs. However, he also stated he believed there “were no cases that we prosecuted that involved any of those 47 deputies.”

Price, meanwhile, has taken a far clearer stance against misconduct at the jail or ACSO in media interviews.

“Once you make it clear to people that you are going to be watching what they do, then things will change,” she told KPFA. “And so the DA does have the ability to open a criminal investigation.”

But it’s not just the sheriff’s office that is plagued with misconduct. Last year, an attorney from the Alameda County Public Defender’s Office filed a motion to remove the entire DA’s office from a murder case, which claimed that O’Malley refused to fire attorneys accused of wrongdoing and fostered a “troubling and extensive pattern of misconduct” at the office. The motion alleged that O’Malley’s office had withheld exculpatory evidence, made improper arguments to the jury, and committed other acts of misconduct.

The motion did not mention another high-profile recent incident, in which a prosecutor was found to have secretly recorded attorney-client conversations. Wiley told KPFA that the prosecutor-in-question is still working in the District Attorney’s office. When asked if he would further discipline the attorney if he were to be elected, Wiley stated he would not and added that the individual is a “hard-working, excellent DA who made a mistake.”

It’s important to note the human costs of these mistakes. Many cases went through the Alameda County DA’s office in which victims were later exonerated, including that of Ronald Ross, who served almost seven years for an attempted murder conviction before his innocence was proven. Johnny Williams, falsely convicted of child sexual assault, served 14 years before DNA evidence exonerated him. Deshawn Reed, falsely convicted of a double-murder, served seven years. In other cases, the DA’s office dropped charges or failed to convict high-profile defendants: In 2021, Patrick Willis, who served almost 10 years of a life sentence for an alleged double-murder, had his case dropped entirely after he’d been granted a new trial. In 2020, a state appellate court reversed the murder conviction of Shawn Martin, after a prosecutor in O’Malley’s office was found to have improperly quoted the law at trial. A jury acquitted Martin the following year.

Price has taken a hard stance against the misconduct alleged at the DA’s office under O’Malley and Wiley. She has also criticized the closeness between the DA’s office and members of law enforcement. Since O’Malley took office in 2009, her office has charged just one officer for a fatal shooting. Wiley tried the case. While both candidates have said that Attorney General Rob Bonta should investigate on-duty shooting cases to increase objectivity, Price has taken a far stronger stance against prosecutorial and police misconduct.

“We will no longer have a double standard in Alameda County where if you are a regular resident and you violate someone’s rights, we come after you with the full force and the power of the state, but if you are a law enforcement officer and you violate someone’s rights, even to the point of death, that we give you a pass,” she told KPFA. “That cannot happen.”