Your Essential Criminal Justice Guide to Election Night

From sheriffs to bail to marijuana, and more—here’s what you need to know.

It may be Donald Trump’s America, but in local elections this year, candidates from both parties are shying away from “tough on crime” campaigning and instead promising to reform the criminal justice system. Prosecutors and sheriffs who hold tremendous discretion in shaping law enforcement policies are on the ballot in hundreds of counties—as are referendums and statewide contests that could transform prosecution and sentencing rules. Candidates are talking about cash bail reform, trumpeting their support for diversion programs, highlighting their concern about racial disparities, and promising that they will not participate in federal operations that target immigrants.

“It’s a testament to the influence the movement has had in shifting the field,” Udi Ofer, the director of the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice, told The Appeal.

Reform advocates have scored decisive wins in recent years, whether by electing prosecutors like Larry Krasner, who ran on targeting mass incarceration, or by directly persuading voters to reduce aggressive sentencing through referendums. This year alone, in a series of primaries, such as in St. Louis County; Cole County, Missouri; and Bexar County, Texas, candidates running on reforming the criminal justice system ousted prosecutors who favored more aggressive tactics and issued alarmist public safety warnings. And incumbents under political pressure from activists have embraced important reforms, as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo did when he signed into law the country’s first commission to investigate prosecutorial misconduct weeks before facing a Democratic primary.

Still, as reform rhetoric becomes more popular, it is clear that candidates are using it to refer to vastly different policies. “It’s easy to say yes” to diversion, Danny Carr, a candidate for district attorney in Jefferson County, Alabama, said during an October debate in which he and his opponent both voiced support for such programs. “The better [question] is, would you broaden the types of cases that are eligible for diversion programs?” Similarly, many prosecutorial candidates are pledging to ensure that no one is jailed because they are too poor to post bail, but the impact of such promises will hinge on how they define indigent status, or for which exact charges they will refrain from seeking bail. And then there are incumbents like Erica Marthage, the state’s attorney in Bennington County, Vermont, whose electoral enthusiasm for alternatives to incarceration belies a punitive record.

Many politicians still use the usual playbook of attacking opponents as “soft on crime” or hostile to policing. According to Ofer, Florida’s and Georgia’s gubernatorial elections “will be looked at as a defining moment for tough-on-crime versus smart justice platforms.” Some local elections feature similar clashes, sometimes in conservative jurisdictions like Oklahoma’s Payne and Logan counties.

But the pressure that many candidates face to steer clear of conventional promises of aggressive prosecution speaks to the changing politics of criminal justice reform. All in all, The Appeal: Political Report has identified and previewed 45 state and local elections where some important aspect of the criminal justice system is at stake on Tuesday. Some trends emerge.

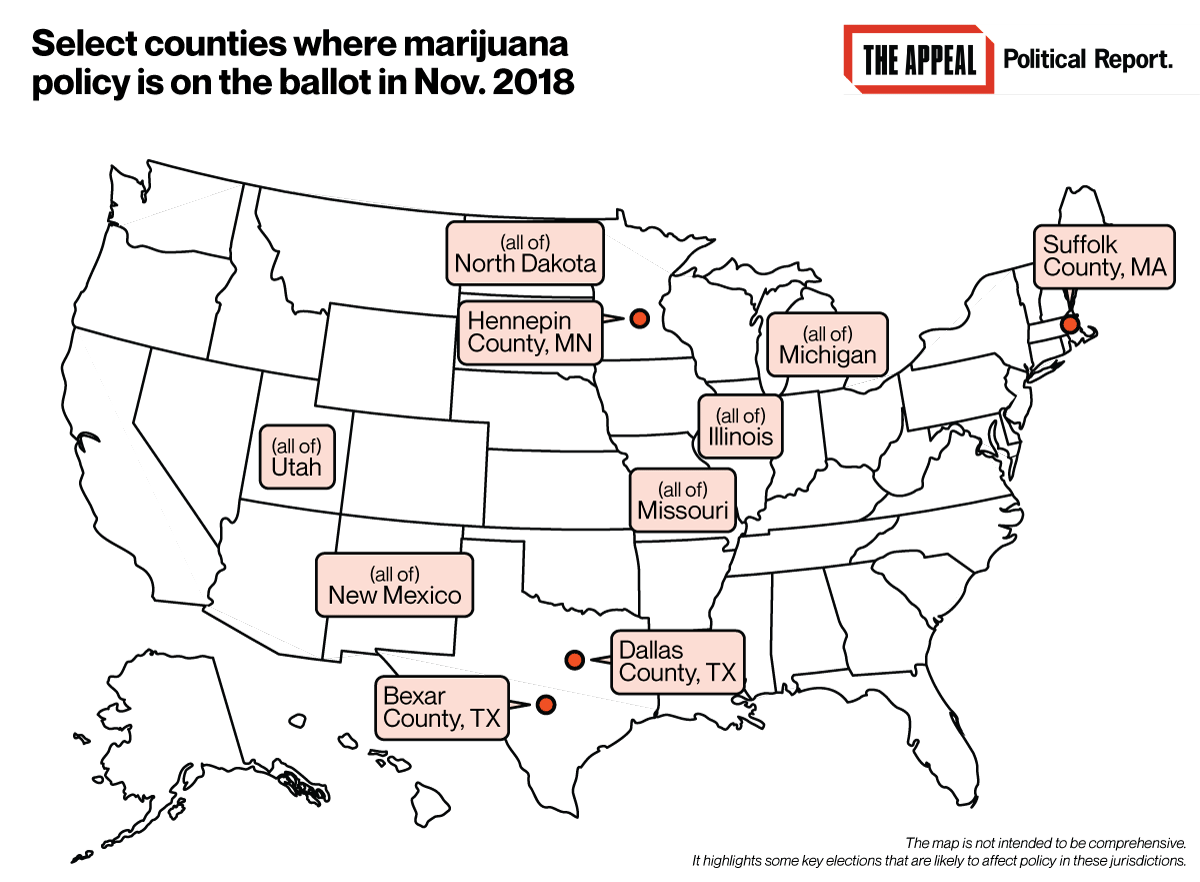

Many routes to marijuana reform

The movement to legalize marijuana has a lot riding on Election Day. Four states might legalize the drug by referendum: Michigan and North Dakota for recreational use, and Missouri and Utah for medicinal use.

Victories by governors who back marijuana legalization—including JB Pritzker (Illinois), Tim Walz (Minnesota), Gretchen Whitmer (Michigan), Michelle Lujan Grisham (New Mexico) who are all favored to win, as well as candidates locked in tighter contests such as Andrew Gillum (Florida), Ben Jealous (Maryland), and Ned Lamont (Connecticut)—could alter the legislative landscape on this issue. Pritzker and Grisham in particular are likely to govern alongside a Democratic legislature. In Michigan, Whitmer’s win could facilitate the referendum’s expansion into legislation to expunge past convictions.

North Dakota’s referendum already contains that additional step toward expungement; it would seal the records of people who have completed their sentence for most marijuana convictions, but it would not alter the sentences that people are currently serving. “I think in past years the focus had been on creating the system for moving forward, and now that that’s become less of an unknown people are more comfortable looking back and looking at past convictions,” Mason Tvert, the spokesperson for the Marijuana Policy Project, told The Appeal.

In states that have not legalized marijuana, prosecutors have wide latitude for handling cases—whether they file charges at all, and if so how severe they are. Many candidates for district attorney are now promising to use their discretion to limit, if not eliminate, marijuana charges, or else to treat these cases as civil infractions instead of criminal offenses.

John Creuzot, who is running for district attorney in Dallas County, says that he would no longer charge first-time marijuana possession cases, while Joe Gonzales, running in Bexar County, wants to strengthen the county’s cite-and-release program. In Minneapolis, the disparity in marijuana possession arrests between African Americans and whites was elevenfold according to an ACLU study from 2014; Mark Haase, who is running to be county attorney in Hennepin County (the jurisdiction that includes Minneapolis) has pledged to not charge any marijuana offense absent “circumstances like very, very large amounts or sale to a minor.” And in Boston, Rachael Rollins has gone a step further by stating that her default policy if she is elected district attorney would be to not prosecute any drug possession charges.

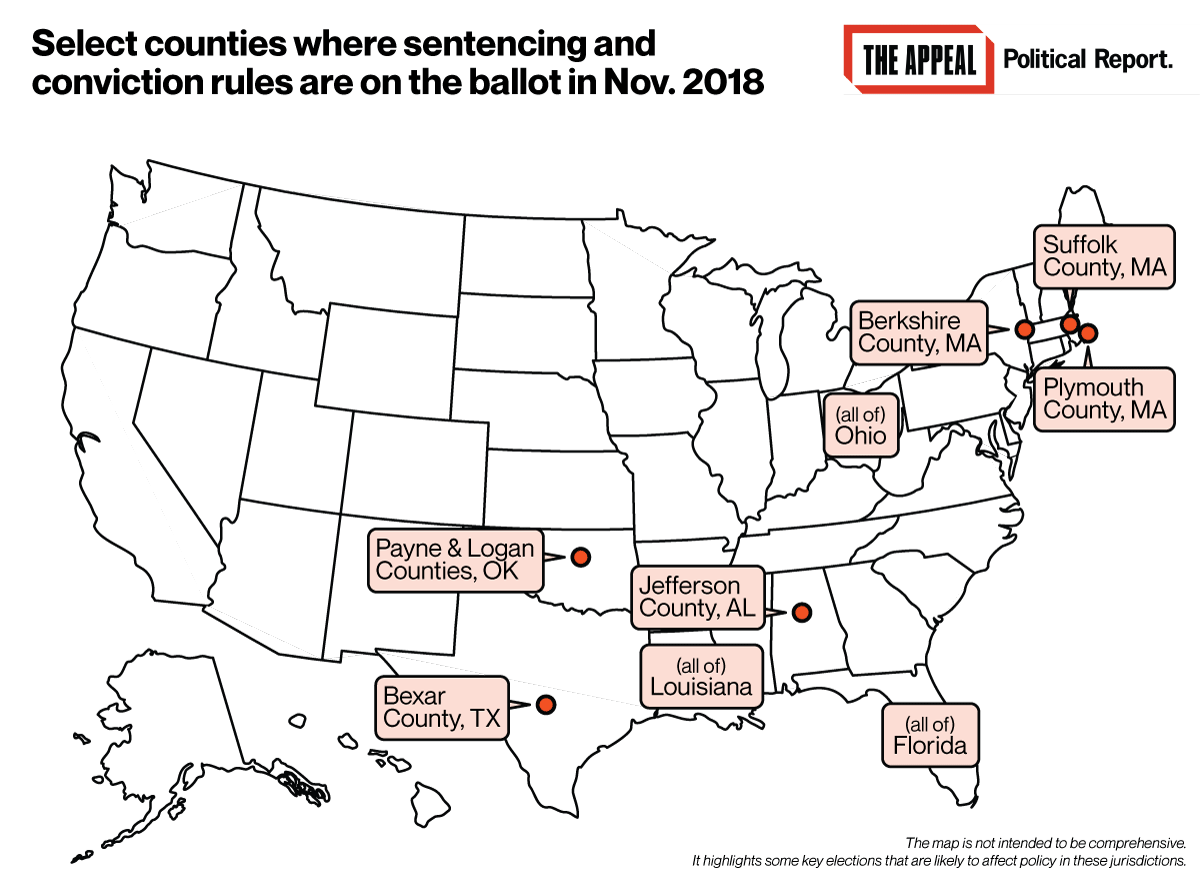

Reforms to sentencing and conviction rules target mass incarceration

Efforts to curb unequal convictions, shorten sentences and reduce the severity of charges will appear on ballots all over the country on Tuesday.

Louisiana’s Amendment 2 takes aim at the state’s racial disparities. It would no longer allow non-unanimous juries to render guilty verdicts for felonies, a vestige of the Jim Crow-era Constitution that still results in Black Louisianans’ disproportionate incarceration, as a New Orleans Advocate investigation showed this year.

Two initiatives promote changes to past convictions. Floridians could strengthen the hands of lawmakers who wish to reduce the existing prison population by passing Amendment 11, which would enable new sentencing reforms to be applied retroactively; Florida’s Constitution currently imposes uniquely harsh limits on the legislature’s ability to reduce sentences that people are already serving. In Ohio, the Issue 1 referendum downgrades possessing any drug to a misdemeanor, and enables people who are already serving a sentence for drug possession to seek a new, reduced sentence.

Mandatory minimum guidelines, another major obstacle to decarceration, could face renewed pushback if critics of the guidelines win. In Florida, where lawmakers from both parties have called for sentencing reform, the viability of such rollbacks hinges on who will wield the governor’s veto pen; Republican gubernatorial nominee Ron DeSantis supports maintaining mandatory minimums while Gillum, his Democratic opponent, supports letting judges occasionally override them.

Massachusetts could be in for a change as well. In 2015, 10 of the state’s 11 DAs signed a letter in defense of mandatory minimums that lawmakers were targeting. The possible elections as district attorney of Rollins in Boston, Andrea Harrington in Berkshire County, and John Bradley in Plymouth County would give state reformers new allies.

Prosecutorial candidates who are seeking to reduce the prison population have also converged on targeting the effects of fines and fees that courts impose on defendants. Many individuals who cannot afford these costs are jailed, a cycle that Carr has pledged to break in Jefferson County, Alabama.

More indirectly, the presence of fines and fees can result in harsher sentences. In Bexar County, Texas, defendants must pay a steep fee to access the less punitive diversion programs. One of the district attorney candidates, Joe Gonzales, denounced this as a “pay to play” system. In Payne and Logan counties in Oklahoma, DA candidate Cory Williams says he would curb prosecutors’ habit of charging defendants with felonies to extract higher fees from them.

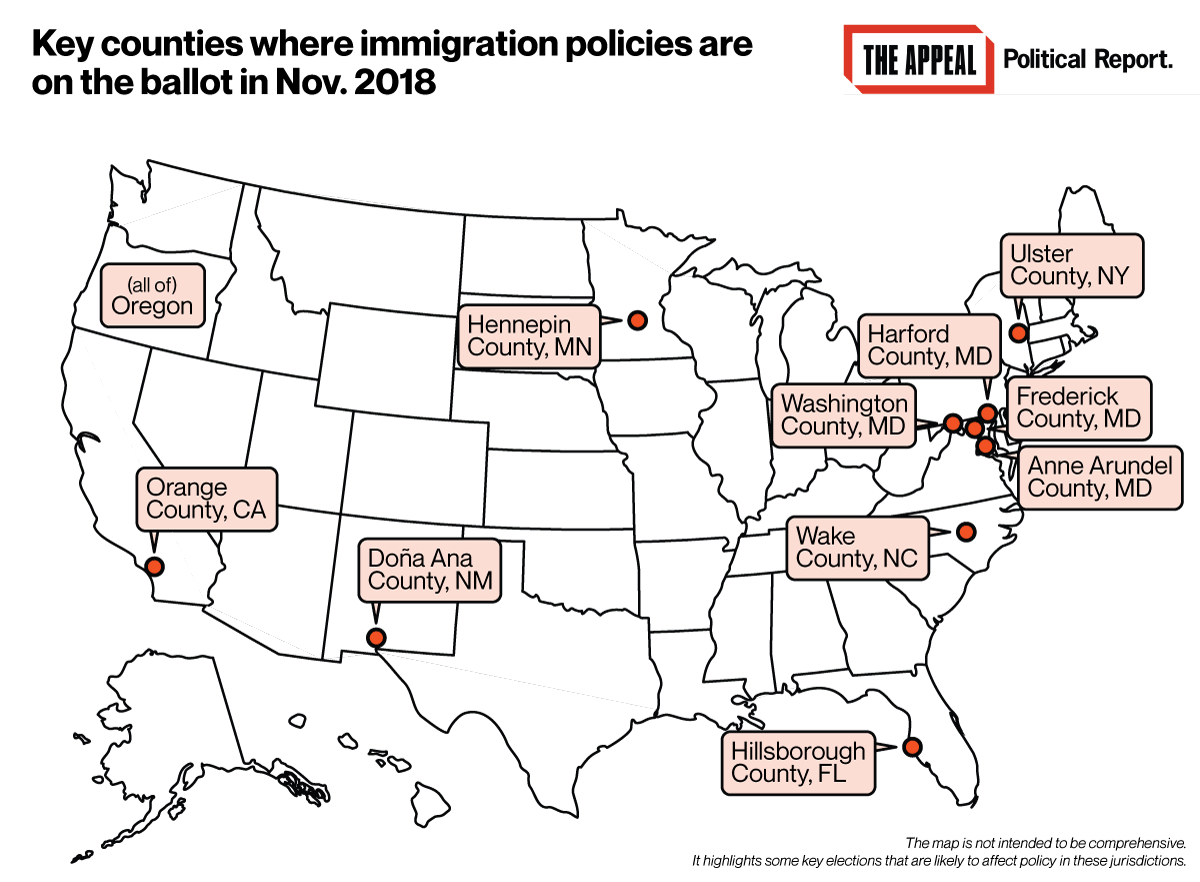

Local cooperation with ICE could expand—or contract

To amplify its reach, ICE uses a variety of agreements with local law enforcement. The most visible type of agreement is the 287(g) deal that authorizes local deputies to act like federal immigration agents by investigating the status of people they detain. Other modes of cooperation can be more informal and harder to track. They include providing ICE with lists of foreign-born individuals held at county jails, giving ICE office space in said jails, or agreeing to detain people that ICE has arrested in exchange for nightly payments.

Tuesday’s elections for sheriff or county executive—the officials who often decide a county’s cooperation with ICE—will be decisive for the fate of many such partnerships.

The scope of the potential change is limited by the fact that many politicians who criticize ICE also argue that their county would suffer too big a financial hit if they severed their existing relationship with the federal agency. Immigrants’ rights advocates counter that more is at stake. “What kind of public servant do you want to be,” Johana Bencomo, the director of community organizing at NM CAFé, told The Appeal in reference to this dynamic unfolding in Doña Ana County, New Mexico. “Do you want to be one that’s attached to money or one that’s serving your community and what your community needs?”

Still, The Appeal has identified 10 counties—plus an entire state—where divergent approaches to local immigration enforcement are confronting one another on Tuesday’s ballot.

Maryland alone features at least four counties in which the fate of a single election will most likely affect participation in the 287(g) program. North Carolina’s Wake County features a similar showdown between longtime sheriff Donnie Harrison and Gerald Baker, a challenger who pledges to withdraw from 287(g). The ACLU has spent $140,000 advertising this election’s impact on immigration policy, an ACLU official told The Appeal.

Elsewhere in the country—from Hennepin County, Minnesota and Hillsborough County, Florida to Ulster County, New York and Orange County, California—sheriffs and undersheriffs who assist ICE are running against challengers who have pledged less cooperation and who warn of straining ties between sheriff deputies and immigrant communities. “All you’ve done is you’ve created hate toward the local law enforcement,” Gary Pruitt, the Democratic nominee for sheriff in Hillsborough County, told The Appeal about current Sheriff Chad Chronister’s deal with ICE.

In Oregon, the Federation for American Immigration Reform and Oregonians for Immigration Reform, organizations that the Southern Poverty Law Center classifies as hate groups, have put forward a referendum (Measure 105) that would repeal the state’s 32-year old “sanctuary” law.

Voters weigh in on prosecutorial and policing misconduct

Sheriffs and prosecutors wield tremendous force but face little oversight, and often little electoral accountability. Seventy-four of Minnesota’s 87 prosecutorial elections only featured one candidate this year, for instance, according to an analysis by The Appeal, a phenomenon in keeping with studies of past cycles.

But voters already rejected the legacies of two of the nation’s most controversial officials already this year. Bob McCulloch, St. Louis County’s longtime prosecuting attorney, lost to Wesley Bell in the August Democratic primary in what was his first contested election since the Ferguson protests of 2014. Milwaukee County ousted Acting Sheriff Richard Schmidt, who had worked under Sheriff David Clarke during a string of gruesome deaths in the Milwaukee jail.

On Tuesday, voters will weigh in on other allegations of abuse or misconduct.

The sheriffs of Hillsborough County, Florida; Santa Clara County, California; Los Angeles County; Frederick County, Maryland; and Wake County, North Carolina, are seeking re-election; The Appeal has recently reported on the abusive detention conditions in jails run by the first three, and on aggressive policing conducted by the latter three’s deputies. Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s contentious re-election race has been shaped by his decision to not charge police officers who shot and killed two Black men. And in Rensselaer County, New York, District Attorney Joel Abelove is running for re-election a year after he was indicted for withholding evidence from a grand jury in the aftermath of a police shooting. (The charges were dismissed in June, though the state attorney general’s office has appealed.)

Local referendums also seek to curb official abuses. Nashville could implement a civilian board to investigate police misconduct, and two Alabama counties may bar sheriffs from personally pocketing funds allocated for food in jails.

Bail reform is on everyone’s lips

“More than any other year, bail reform has become a topic of conversation,” Ofer of the ACLU says, referring to the demands to overhaul a system that keeps many poor individuals in jail before trial because they cannot afford the financial conditions set for their release.

In New York, the urgency of overhauling this system has drawn more attention since Kalief Browder, a teenager incarcerated for three years without a trial because his family was unable to pay bail, died by suicide in 2015. Last year, Selmin Feratovic died on Rikers Island while held on a $50,000 bail. An audit revealed that in 2016 about 76 percent of the people jailed on a given day in New York City had not yet been tried, and that a majority of these pretrial detainees are there because they cannot afford bail.

Despite the pressure created by such cases, change has proved elusive so far in New York. Reform efforts stalled in the state Senate this year. Two Democratic candidates who won primaries for the state Senate told The Appeal in September that they would prioritize such legislation in the upcoming session; that plan is most likely dependent on whether their party wins a majority in that chamber on Tuesday.

Here again prosecutors have a great deal of influence because they often have leeway in the bail amount and conditions they seek. Candidates like Bell, Rollins, or Bradley have pledged to eliminate the use of cash bail for some offenses or to ask for more releases on personal recognizance, which enable people to be released pretrial without owing a payment. Jealous and Gillum, as well as Stacey Abrams of Georgia, all feature bail reform in their gubernatorial platforms.

Judges also enjoy discretion in deciding how to set bail. In Harris County (the Texas jurisdiction that includes Houston), Democratic challengers have made this into an issue against the county’s misdemeanor judges in the wake of a court ruling that found that Harris County’s bail practices violated defendants’ rights.

But as promises to reform the bail system become ubiquitous, Ofer acknowledges that some of the candidates lack a sufficiently specific or daring vision of what it should entail. Vague slogans have served as cover for toothless changes, and poor reforms can worsen the situation if they replace cash bail with alternatives that increase pretrial detention, as Ofer believes California did this year. Still, he argues that the spread of this message represents progress. “It shows success by the movement that the issue has elevated to such prominence that candidates feel that they have to take a pro-bail reform position,” he said.

“The job of advocates,” Ofer added, “is going to be to fill the gap in what bail reform means.”