‘You Don’t Own Me’

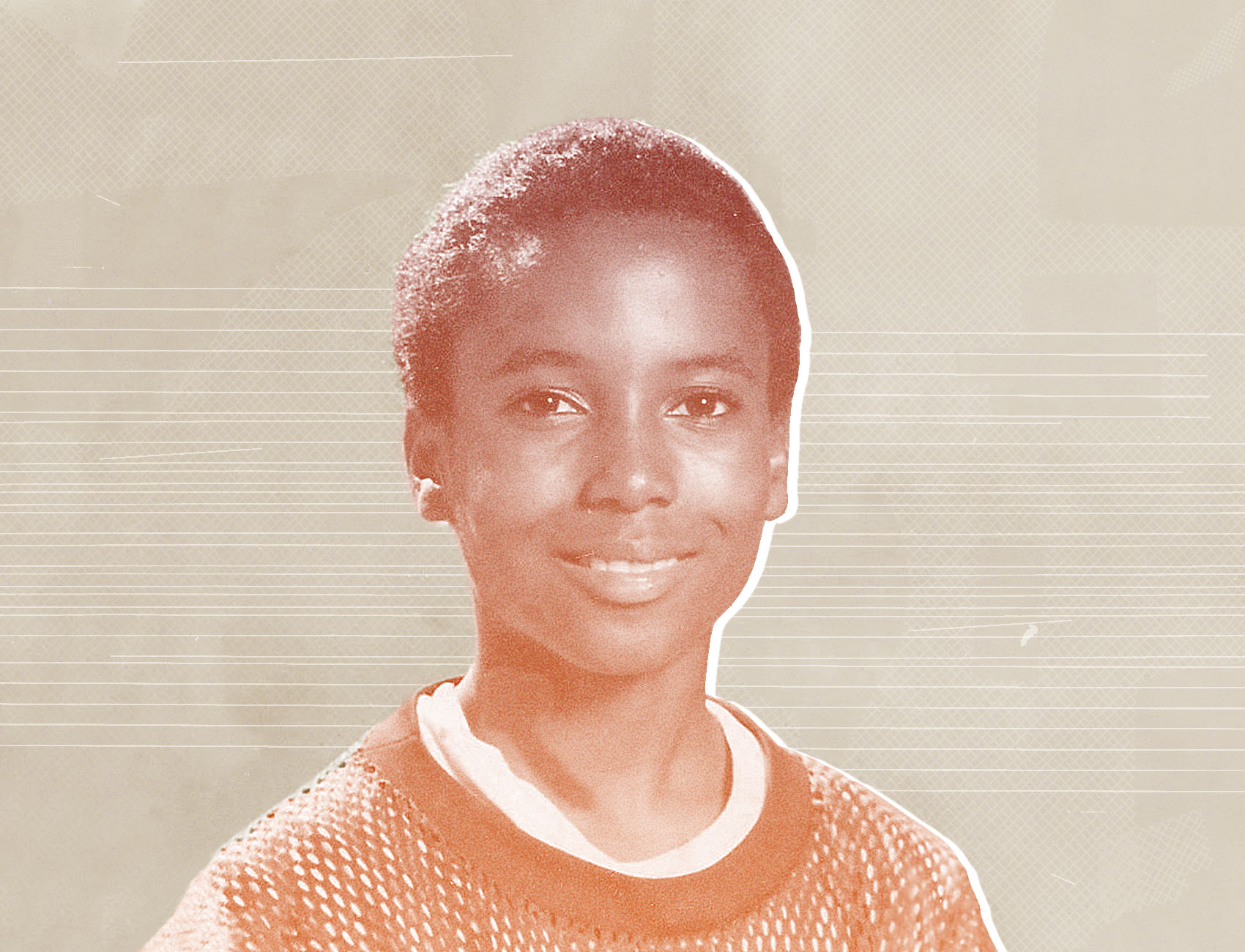

At 16, Larry Rosser was imprisoned for killing a woman who sexually and physically abused him. He served 22 years in the California prison system before being released in 2017, after parole commissioners became convinced he was a rehabilitated victim.

It was the early fall of 1994. For two years, Los Angeles teenager Larry Rosser had been subjected to physical and sexual abuse by a female member of the Crips.

Felicia Stephens, a 24-year-old high-ranking member of the Hoover Crips, slapped, punched, kicked, spit on, bludgeoned and belittled him. Although he wasn’t forced to sell drugs for the gang, Rosser said he felt trapped in his non-consensual sexual relationship with Stephens.

During the afternoon of Oct. 19, 1994, Stephens confronted Rosser, then 16. “You don’t own me,” Rosser declared. “You’re going to always be mine,” Rosser later recalled her saying. “You got no say in the matter.”

Stephens approached Rosser with a brick in her hand, but Rosser drew a handgun from his pocket. “I’m not going to let you hit me with the brick,” he warned. He then fired the weapon three times, striking her once in the chest and twice in the back. Stephens succumbed to her injuries while being transported to a hospital.

On Feb. 22, 1996, Rosser went to trial on first-degree murder charges in Los Angeles County criminal court. Prosecutors said that Rosser’s actions constituted first-degree murder because Stephens had dropped the brick before Rosser fired the first shot. But Rosser’s public defender called two witnesses who testified that Rosser had not left the corner where he had sold drugs that afternoon to retrieve the gun, or that he said anything about the offense to suggest that his actions were premeditated.

On March 4, 1996, a jury convicted Rosser of a lesser offense, second-degree murder. Later a judge sentenced Rosser to the mandatory minimum punishment of 15 years to life, plus four years because he used a handgun during the commission of the crime.

In a statement emailed to The Appeal, the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office said it “has a long-standing practice of considering the age of the defendant, along with the circumstances of the crime and the history of violence between the defendant and the victim, in any domestic violence murder prosecution.”

On Aug. 12, 2013, Rosser became parole eligible after serving 17 years in the California prison system. At Rosser’s 1996 trial, his attorneys did not raise victimization as a defense, so his parole attorneys set out to ensure that the Board of Parole Hearings would consider the intimate partner violence he experienced as well as his age at the time of the offense.

In advance of his second parole hearing in 2016, an expert in forensic and clinical psychology evaluated Rosser for evidence of intimate partner battering. Rosser was “feeling fearful, trapped, and overwhelmed,” wrote Dr. Nancy Kaser-Boyd. “In similar situations with battered women, it is often found that the person has a subjective perception of the need for self-defense.”

Rosser, who is Black, faced an enormous hurdle to freedom, however: racial disparities in parole for young people sentenced to life imprisonment. Thanks to a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings—including Graham v. Florida in 2010 and Miller v. Alabama in 2012 which held that except in rare cases, it is cruel and unusual punishment to sentence a young person to life in prison—life without parole sentences for youth were barred “for all but the rarest of juvenile offenders.” The Supreme Court also required states to provide juvenile lifers like Rosser with a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.”

But a study in the Summer 2019 volume of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review highlights Rosser’s challenges. The study included a review of 426 California parole decisions among people sentenced to life with the possibility of parole for crimes committed as juveniles. It showed that the odds that Black people were granted parole were 2.7 times lower than non-Black people with similar institutional records. The study also concluded that the odds that people who retained a private attorney instead of state-appointed counsel received parole were approximately 3.4 times higher.

Kristen Bell, an assistant professor at the University of Oregon law school, is the study’s author and was also Rosser’s attorney during his third parole hearing. Bell found that California’s juvenile parole system “is arbitrary and capricious” because it lacks an objective standard for release.

“The individuals making parole decisions are human beings with a very difficult job,” Bell told The Appeal. “The problem with the parole system is not that the decision-makers have discretion, it’s the sheer amount of discretion they have.”

In addition to the Supreme Court rulings, California had set its own standard for improving the treatment of people sentenced to prison in their youth. Enacted in 2013, Senate Bill 260 instructed parole boards to “give great weight to the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to adults, the hallmark features of youth, and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of the prisoner in accordance with relevant case law.”

Rosser had participated in rehabilitation programs, including anger management, behavior modification, and counseling for substance use disorder. But he was denied parole during his first hearing on Sept. 11, 2014. On Feb. 19, 2016, he was denied a second time.

According to transcripts from his 2014 and 2016 parole hearings, board commissioners who denied his release said they wanted Rosser to accept responsibility for the gang life he had led before he killed his abuser. They also appeared to downplay the role that abuse played in Rosser’s offense.

“I felt it was important for them to know what I was up against—why I was afraid, why I panicked—to get them to see it from my point of view,” Rosser told The Appeal in his first-ever interview about his case. “But I don’t think they cared much about that.”

Rosser was right. Ali Zarrinnam, a now former parole commissioner who presided over Rosser’s 2016 hearing, told him “you liked her, you liked the sex. You were willing to take the little bit of battering, in exchange for what you were benefiting from it. Right?”

Bell said that Rosser’s case “illustrates many ways in which our system is unjust. Would the board have framed the questions in the same way if it were asking someone who looked like me, a small white woman, rather than Larry, a Black man who was small as a child, who is now twice my size? To be clear, the ‘sex’ they were asking about was statutory rape. That’s what we call sex between a 14-year-old and a 22-year-old.”

In a statement emailed to The Appeal, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s Board of Parole Hearings confirmed that, per SB 260, its commissioners are required to give “great weight” to the diminished capacity of young people as well as growth and rehabilitation they have demonstrated while incarcerated. The spokesperson did not comment, however, on why commissioners did not find Rosser suitable for parole during his 2014 and 2016 hearings.

But Bell argued in a brief to the California Supreme Court that parole commissioners had not given appropriate weight to Rosser’s rehabilitation efforts, his youthfulness at the time of the offense and his status as a survivor of intimate partner abuse. On Aug. 23, 2017, Rosser was finally granted parole. In December 2017, Rosser walked out of Kern Valley State Prison after 23 years of incarceration.

Rosser is now 41 and has a job in a trucking yard working for his godmother’s nephew, hundreds of miles from his old neighborhood in Los Angeles. He rents a room in an apartment in Northern California, where he participates in post-release rehabilitation workshops for parolees.

Family members say Rosser’s transformation has made them proud. “Twenty-three years, that’s a long time to give up a life,” Opal Allen, Rosser’s godmother, told The Appeal. “But at least, at the end, he’s still alive. How many guys survived the gang activity?”

Allen, 71, occasionally housed Rosser when his mother, who struggled with substance use disorder, could not care for him. She said that the criminal legal system harmed Rosser at a vulnerable moment, when he was growing from a young boy ensnared in gangs who endured abuse into a responsible man. “He just got gross, unfair treatment,” she said. “The good thing about it is Larry was sharp enough and keen enough to start checking things out. Everywhere he went, someone would tell him, ‘Man, I looked at your file. You shouldn’t be here.’”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that according to a study published in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Black people were 2.7 times less likely to be granted parole compared to non-Black people with similar institutional records. And that the study also concluded that people who retained a private attorney instead of state-appointed counsel were approximately 3.4 times more likely to be granted parole. But the study showed that the odds that Black people were granted parole were 2.7 times lower than non-Black people with similar institutional records. The study also concluded that the odds that people who retained a private attorney instead of state-appointed counsel received parole were approximately 3.4 times higher.