Years After Protests, NYPD Retains Photos of Black Lives Matter Activists

The records raise questions about the department’s compliance with its protest monitoring rules.

It was Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2015. Black Lives Matter protests were still erupting across the country, and M.J. Williams, a lawyer and activist, was excited to get more involved. The month before, Williams had started to attend weekly protests at New York City’s Grand Central Station. That day, she was at Foley Square, and activists from the group organizing the weekly demonstrations had invited her to join them in a small, nonpermitted march up to Grand Central. The march hadn’t been publicized on social media, and organizers intended to take authorities by surprise.

“One of them saw me and said quietly, ‘Hey M.J., we’re going to be doing a wildcat march up to Grand Central. Do you want to come?’” she recalled. “So I went over to that group and we began marching north.” Only eight or nine people had been told about their plans, she remembers, but within about 25 minutes, police had figured out where they were and cut off their route. “More cops were there than protesters, so much so that we decided to take the subway.”

At the time, Williams thought nothing of this encounter, since police were responding to protests across the city. But over the next few months, Williams began to fear that the NYPD was somehow getting inside information on their plans. Though the movement in New York began to fade in early 2016, Williams continued to think about the NYPD’s potential surveillance of activists, and helped litigate several Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests to get public records on the department’s activities.

The records she helped obtain over the past few years corroborated her fears. One release revealed that the department had undercover officers at the protests. Another showed that NYPD was frequently filming activists.

Now a new release, which Williams shared with The Appeal, shows that the NYPD has maintained dozens of photos of activists who took part in the protests over four years ago. The photos were attachments from emails sent from late 2014 to early 2015 between NYPD personnel, discussing specific protesters and their movements. The emails include intelligence gathered by undercover officers, photo attachments of protesters at demonstrations across New York City, and social media posts from Twitter.

Williams and other advocates say the years-long retention of these photos and social media posts raises serious questions about whether the NYPD is violating its own protest policing regulations, known as the Handschu Guidelines, which limit what protest materials it can retain in the absence of potential unlawful activity.

There are First Amendment questions about how long you can keep and access these photos.

Rachel Levinson-Waldman Brennan Center for Justice

Rachel Levinson-Waldman, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program, said the photo retention also raises First Amendment concerns.

“There are First Amendment questions about how long you can keep and access these photos,” she said. “How is it being used and kept? These practices could potentially chill First Amendment activities. I would have a concern if [photos of] basically innocent third parties are living in these files and being used for other reasons. What protections do they have?”

Photos on file

The Handschu Guidelines were established by consent decree after a 1985 class action suit, Handschu v. Special Services Division, in which a group of political activists successfully challenged NYPD surveillance practices.

The guidelines state that the NYPD is authorized to attend any public event, on the same terms and conditions as members of the public generally, for the purpose of detecting or preventing terrorist activities. But, the department may not retain “information obtained from such visits” unless “it relates to potential unlawful or terrorist activity.”

Williams says the release of these photos suggests that the images are not part of a current investigation because, as she knows from past responses she has received from the NYPD, the department would otherwise have withheld them. The NYPD did not respond to requests for comment about that assertion.

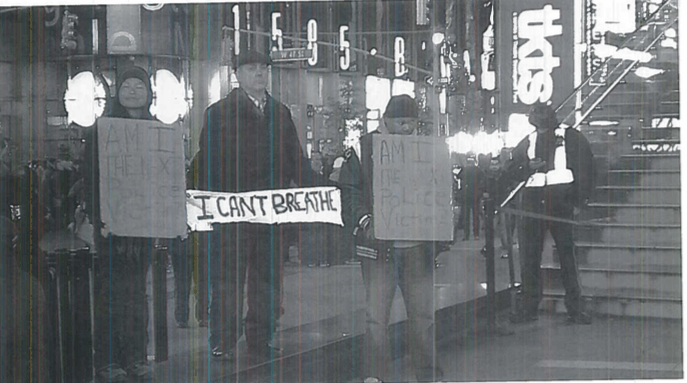

The photos themselves show scores of activists at numerous demonstrations from the final week of November 2014 into the first three weeks of January 2015.

Some of the photos include individuals wearing masks or carrying bags during the marches while others are of people just standing around.

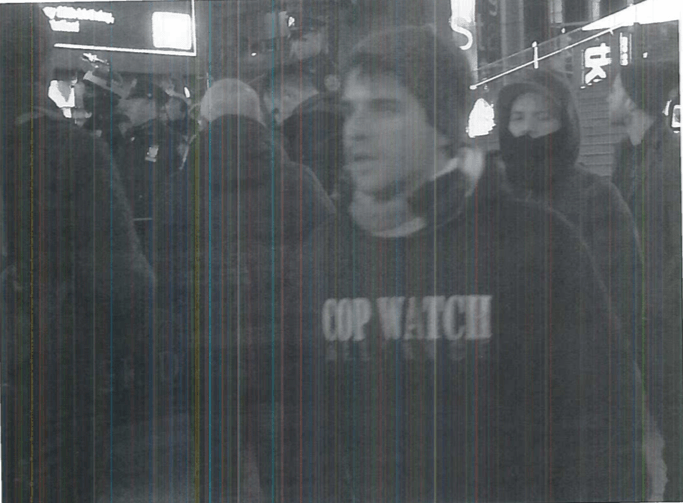

One of the photos shows Daniel Schneider, a member of Cop Watch, a group that films police-community interactions, standing at Times Square, wearing his group’s sweatshirt.

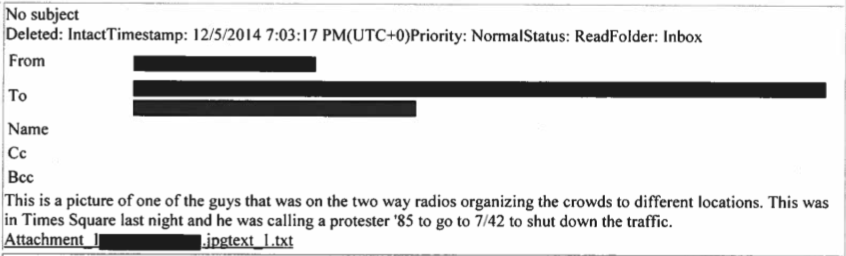

According to the emails, released alongside the attachments, police appeared to believe that Schneider was a main protest organizer. “Coordinator at times square… has walkie talkie,” states one message from 5:06 a.m. on Dec. 5, 2014.

That afternoon, NYPD officials appeared to have shared the same photo of him again, referring to him as “one of the guys that was on the two way radios organizing the crowds to different locations.”

Schneider, who reviewed the photos from that day, said he was using his walkie-talkie to stay in touch with other Cop Watch activists, and was not directing the marches. He said seeing himself in the images was no shock, given how frequently the NYPD films protests.

“I wasn’t surprised since almost every demo I’ve been to, there’s almost always an officer with a video camera that walks by,” Schneider told The Appeal. “The fact that they still have the photograph after all this time is concerning,” he continued. “State surveillance of people exercising their rights is not something that should occur. I don’t think that’s right, it’s a way to stymie political speech and action.”

Schneider wasn’t the only Cop Watch member photographed by police. They also released another image of a person wearing a Cop Watch sweatshirt, back turned, filming police.

State surveillance of people exercising their rights is not something that should occur.

Daniel Schneider Cop Watch

The photo records also include several screenshots of people’s social media posts, which appear to have been shared with top officials at the NYPD’s Intelligence Bureau, including Chief Thomas Galati, according to the accompanying released emails. Some of these include information about planned protests; others are redacted.

Martin Stolar, an attorney who helped win the Handschu settlement, says that he and other attorneys involved in the settlement are considering whether the retained photos are part of “a pattern and practice of unlawful activity.” If the lawyers decide the NYPD’s conduct was unlawful, and not isolated, they could raise the matter in court. “We are reviewing and haven’t made a determination yet,” Stolar said by phone. “All I can tell you is we haven’t gone to court on anything yet.”

Redacted sources

In addition to concerns about photo retention, the NYPD’s description of the redactions in the records raises questions about their intelligence-gathering techniques. According to the NYPD, the redactions include not only “personally identifying information of NYPD personnel such as names and email address,” but also “any references that may identify any sources as well as any references to non-routine law enforcement sensitive procedures relating to the Intelligence Bureau.”

The NYPD did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment about who the redacted sources might be. Joe Giacalone, a retired NYPD detective sergeant and an adjunct professor at the City University of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, says the phrase could refer to any number of sources, including but not limited to confidential informants.

“If you have a confidential informant working in the group, you wouldn’t want to reveal [it],” he said, referring to the redactions. He also noted that sources could be either human, like undercover officers, or technological, like video surveillance. The vague description of the redactions, he continued, keeps people guessing “which helps the intelligence bureau because it makes people paranoid.” If people are scared, he added, they might be less likely to act recklessly. “That’s the idea.”

The presence of an undercover officer or confidential informant could help explain how the police seemed to have information that was confined to only a small group of activists, Williams said. During the 2015 MLK Day protest she attended, which was referenced in a previous NYPD FOIL release, one redacted source sent a message to a police official: “Group at Foley mention that they are going to march over to Grand Central.” Williams says it’s inconceivable that a uniformed police officer overheard their plans because they would not have spoken in close range of one.

“I think it was either someone who was standing so close to us that there was no concern about that information getting out, or someone who was trusted among that group of eight or nine,” she said.

In recent years, the NYPD has been known to use such tactics. In 2013, for example, Occupy Wall Street activists learned that a fellow protester, whom they knew as “Albert,” was actually an NYPD detective named Wojciech Braszczok. Throughout 2012 and 2013, Braszczok posed as an activist, attending meetings, getting arrested at demonstrations, and even showing up at activists’ social events.

On Monday, in a separate FOIL case filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union, a state Supreme Court judge ruled that the NYPD had to turn over records relating to how the department tracked Black Lives Matter activists’ cell phones and social media activity.

Kim Ortiz, an organizer with NYC Shut It Down, a New York Black Lives Matter group, said the knowledge of such tactics has weighed heavily on activists. “Like it or not, you have to operate under the assumption everything is being watched,” she said. “Of course it inhibits my freedom, but that’s the reality, so it’s safest to operate under the assumption that we’re being listened to and watched at all times.”