Wrongly Accused of Rape, Randall Mills Has Been Proven Innocent. But That Doesn’t Mean He’s Exonerated.

Vindication and compensation remain elusive for Tennessee’s wrongly convicted, in part because of the state’s parole board.

On Feb. 14, 2001, Randall Mills was summoned to the chaplain’s office at Northwest Correctional Complex in Tennessee. About a year into his 20-year sentence, he knew this was a harbinger of bad news.

He called home and his mom told him: Mills’s 15-year-old son, Dale, had killed himself. Then the chaplain instructed Mills to hang up the phone; his time was up.

“I wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral or to the gravesite,” said Mills, now 64. “I was able to sit in my cell and cry, think, you know, wonder why. All kind of things going through your mind.”

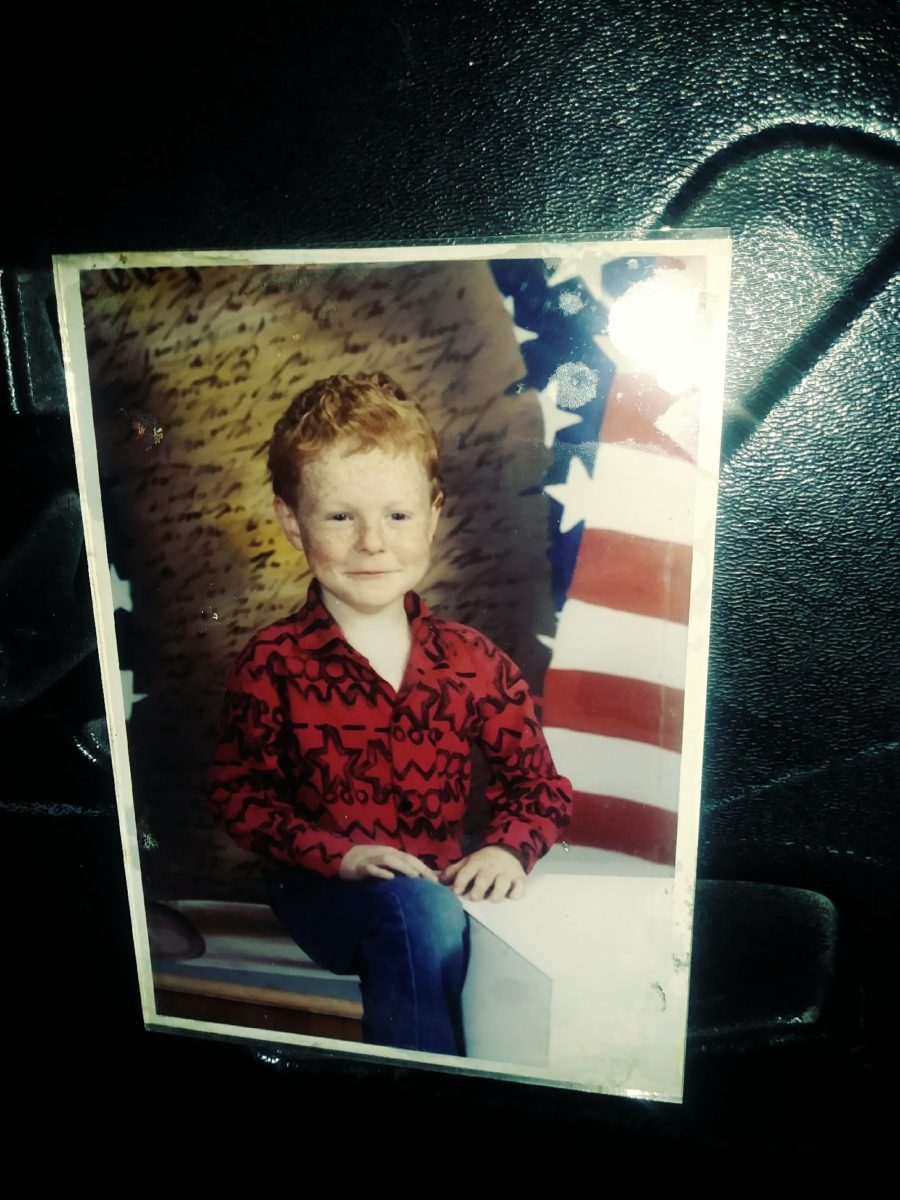

Dale, Mills said, was a “rascal” and a “daddy’s boy” who loved the outdoors. What made the pain even more visceral for Mills was the fact that he shouldn’t have been in prison in the first place.

Mills was accused of raping a 12-year-old neighbor, but as the New York-based Innocence Project and attorney Anne-Marie Moyes with the federal public defender’s office later proved, he was wrongly accused. In 2014, the district attorney’s office dismissed all charges. Mills had served about 11 years in prison and then three more on the sex offender registry. (This reporter worked at the Innocence Project from 2007 to 2015 in the intake and evaluation department.)

“In my mind and my heart I always knew that one day I was going to clear my name,” said Mills, who now lives in Arrington, Tennessee. “Didn’t know how. Didn’t know when.”

But Mills still has one hurdle left to overcome: an exoneration from the governor. Under Tennessee state law, wrongfully convicted people can file for compensation only after the governor has exonerated them. The state parole board evaluates exoneration applications and then makes a nonbinding recommendation to the governor.

On May 1, 2017, the Tennessee Board of Parole denied Mills’s clemency request, without even holding a hearing.

“Mr. Mills’ application and all documents relative to his conviction and appeals were thoroughly reviewed,” Melissa McDonald, communications director for the parole board, wrote in an email to The Appeal. “The facts and circumstances of his case did not merit a formal hearing.” She declined to elaborate.

But Mills has not given up. According to his attorney, Daniel Horwitz, Mills plans to submit another request, this time directly to the newly elected governor, Bill Lee, who took office in January.

Horwitz condemned the parole board’s ruling. “The Board’s decision on Mr. Mills’ clemency application was a complete disgrace, and its members should be ashamed,” Horwitz wrote in an email to The Appeal. “The fundamental problem with Tennessee’s parole board is that it sees itself as a super court that can second guess the judicial system’s determinations regarding guilt and innocence while, at the same time, having none of the tools that are necessary to draw those conclusions.”

Mills isn’t the first person to be stuck waiting for vindication in Tennessee. Lawrence McKinney’s road to exoneration involved multiple battles with the state parole board over several years, according to his lawyer, David Raybin.

McKinney was convicted of rape and burglary in 1978, and sentenced to over 100 years in prison. In 2009, DNA testing results showed he was innocent; his conviction was set aside, the charges were dismissed, and McKinney was released from prison.

But, the parole board twice rejected his request for an exoneration—once in 2010 and again in 2016, according to Raybin.

“The idea of determining someone’s innocence is outside of their skill set,” Raybin said. “Maybe the parole board shouldn’t be tasked with that.”

McDonald said the board had reasons for its decision. “Mr. McKinney’s application, and all documents relative to the investigation, his conviction and appeals were thoroughly reviewed,” McDonald emailed The Appeal. “The Board unanimously agreed that there was not clear and convincing evidence that he did not commit the crime.”

Many rebuked the parole board’s decision and called on then-Governor Bill Haslam to exonerate McKinney, including state legislators, McKinney’s pastor, and the editorial board of the Commercial Appeal. An online petition in support of McKinney garnered more than 12,000 signatures.

In the eyes of the judicial system, Mr. McKinney is innocent.

then-Gov. Bill Haslam Tennessee

Finally, on Dec. 20, 2017, almost 40 years after McKinney was wrongfully convicted, Haslam exonerated him, in spite of the parole board’s findings.

“In the eyes of the judicial system, Mr. McKinney is innocent,” Haslam said in a statement at the time he exonerated McKinney. “While I appreciate the hard work and recommendations of the Board of Parole, in this case I defer to the finding of the court charged with determining Mr. McKinney’s guilt or innocence.”

After McKinney was exonerated, he filed for compensation and was awarded the maximum amount of $1 million. The only other people to be exonerated by the governor and receive compensation under the state’s 2004 statute were Clark McMillan and James Green, according to Jeffrey S. Gutman, professor of clinical law at The George Washington University Law School, who researches wrongful convictions and compensation.

Yet 21 wrongful convictions have been discovered in Tennessee since 1993, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Of those 21, nine people applied for an exoneration; of the nine, five were granted a hearing; and of the five hearings, two were recommended for exoneration, according to McDonald.

About 14 percent of those 21 have been compensated, far below the national average of about 37 percent, according to data compiled by Gutman.

Out of the 33 states (plus the District of Columbia) that have a compensation statute, nearly all mandate a judicial or administrative procedure for establishing eligibility for compensation, which includes an appeals process, he explained. Tennessee and Maine are the only states in which gubernatorial intervention is the sole way to qualify for compensation, according to Gutman’s research.

Issues with the parole board also impact commutation decisions, according to Mills’s attorney, Horwitz, noting the parole board’s controversial role in Cyntoia Brown’s case.

Brown was 16 years old when, fearing for her life, she killed a man who had hired her for sex work. She was convicted of murder and given a life sentence. In May of last year, two of the parole board’s members recommended Haslam accept her clemency application, two said she should serve 25 years, and two rejected her application.

After a push by supporters nationwide to release Brown, Governor Haslam granted her clemency application in January before leaving office, despite the parole board’s mixed recommendation. She is scheduled to be released in August.

Mills hopes Governor Lee will grant him the exoneration he has been fighting for since he was convicted almost 20 years ago. Over the years, Mills’s protestations of innocence have often been met with disbelief. When he went on job interviews, he told prospective employers he was on the sex offender registry but had been wrongfully convicted.

“I know what they’re thinking because it’s what I would have thought, you know: ‘You’re a piece of shit,’” said Mills. “People look at you like you’re lower than a dog, you know, or a snake.

Despite the continued fight for vindication, Mills says he is grateful for the life he has now. He has three grandsons, Landon, 9, Dale, 15—named for Mills’s son—and Liam, 17. He works as a building superintendent for his church in Franklin, Tennessee.

Obviously, there is no way to return to Randy what was taken from him, but at least it is a first step in, most importantly, clearing his name.

Bryce Benjet Innocence Project

Before his conviction, though, Mills had other professional goals. At the time of his arrest he was attending cosmetology school, he said, and he finished classes while out on bond.

“My plans were to go through schooling, get out, open my own shop,” he said. “Give my sons a better life, but that didn’t work out.”

An exoneration from Lee would help repair the “reputational injury” done to Mills, said Bryce Benjet, a senior staff attorney with the Innocence Project who worked on Mills’s case. Lee’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

“Obviously, there is no way to return to Randy what was taken from him, but at least it is a first step in, most importantly, clearing his name,” said Benjet.

Until Mills is exonerated by the governor, he cannot file for compensation. The money, he said, would help make up for the years he was in prison and unable to earn an income. He’s renting a home now; if he receives compensation, maybe he would buy a trailer, he said.

“Financially, I would be OK,” said Mills. “I wouldn’t have to worry about money.”

But an exoneration would signify more than the possibility of financial security, he said.

“To have everyone sign papers and maybe say, ‘Hey, Mr. Mills, we’re sorry this happened,’” Mills said. “It would mean the world to me.”