Will a $1 Million Grant To Fight Sexual Assault Change A DA’s Office Known for Jailing Rape Victims?

The DOJ just gave $1 million to the New Orleans DA for rape kit testing, but advocates question whether real change can come to an office fighting allegations that it threatens, intimidates and jails rape and domestic violence victims.

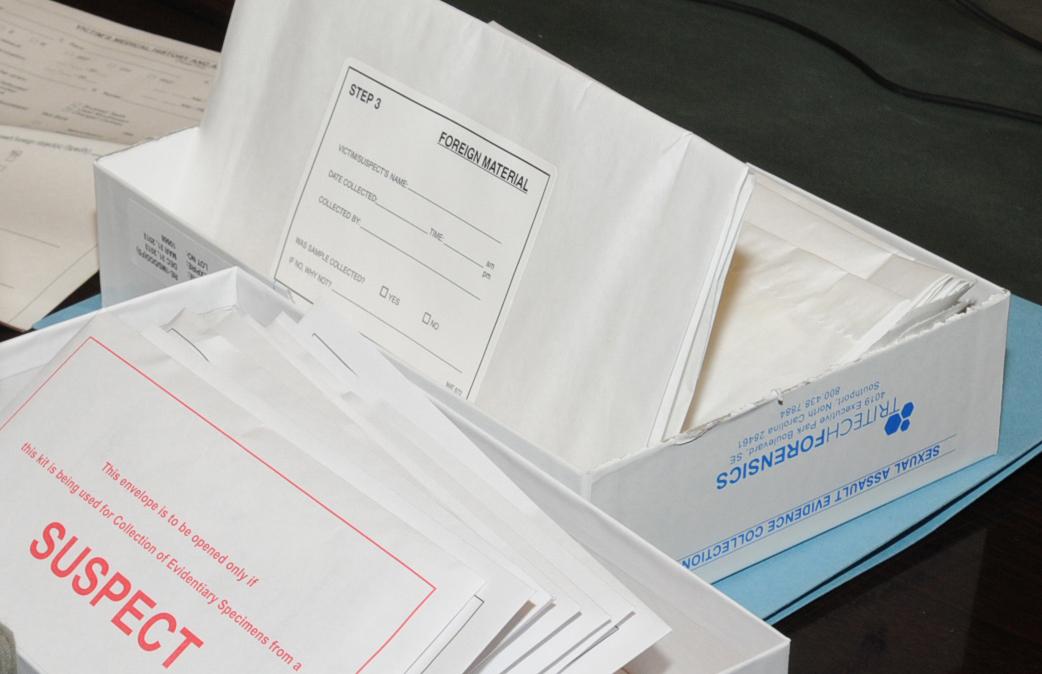

The Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office recently received a three-year, $1 million federal grant to staff new prosecutors, an investigator, and a “victim service advocate” to investigate and prosecute the cases that result from the belated testing of rape kits in New Orleans Police Department storage. The grant is from the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, administered by the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which is giving millions of dollars to the nation’s law enforcement agencies with the worst records on enforcing laws against sexual assault. Orleans DA Leon Cannizzaro has already used the funding to create a new unit to prosecute neglected rape cases, and NOPD received $1 million in 2015 to test rape kits and create a plan to prevent another backlog.

“DNA empowers women in rape cases,” said Assistant District Attorney Laura Rodrigue. “It gives them strength in numbers and it’s people all coming together behind them.”

But seven-figure grant money to law enforcement for rape kit testing doesn’t address the reasons that they weren’t tested in the first place. Sexual assault investigations require significant police work like interviewing victims, tracking down witnesses, and corroborating accounts of victims. But instead of doing the needed legwork, police routinely downgrade rape cases, close them by classifying them “unfounded,” meaning false or baseless, or refuse to fill out police reports at all. Furthermore, police departments do not report such cases to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR), which collects data from over 18,000 law enforcement agencies and publishes widely used annual reports.

Front-end investigative failures in sexual assault cases are particularly common in New Orleans. In 2009, a Times-Picayune investigation found that the NOPD, which had touted a decline in rape, classified over half of sex crime allegations reported in 2008 as miscellaneous, noncriminal incidents. No official reports were created for these complaints and they were not reported to the FBI. The department’s reported rape rate unbelievably fell below the reported murder rate.

At the time, NOPD denied that it misclassified cases. “If it is a rape or a sexual assault, it is a sexual assault,” said then NOPD Assistant Superintendent Marlon Defillo. “There is no gray line with respect to that. We call it the way we see it.”

But in 2010 and 2011 when the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division investigated the NOPD for patterns and practices of illegal police misconduct, the agency found that the department “misclassified large numbers of possible sexual assaults, resulting in a sweeping failure” to properly investigate sex crimes. According to the DOJ, NOPD’s “investigations are seriously deficient, marked by poor victim interviewing skills, missing or inadequate documentation, and minimal efforts to contact witnesses or interrogate suspects” as well as “replete with stereotypical assumptions and judgments about sex crimes and victims of sex crimes, including misguided commentary about the victims’ perceived credibility, sexual history, or delay in contacting the police.” For example, officers asked victims to fill out and sign a document stating they did not want to file charges or proceed with an investigation or prosecution. The document, called a “Voluntary Victim/Witness form,” included information about Louisiana’s criminal mischief statute, suggesting victims could be prosecuted for filing a false police report. DOJ further found that even when officers properly classified sexual assaults, investigative reports often omitted crucial details like descriptions of a victim’s injuries or results of forensic exams.”

In 2012, the city of New Orleans and the DOJ entered into a consent decree “with the goal of ensuring that police services are delivered to the people of New Orleans in a manner that complies with the Constitution and laws of the United States.” The agreement required the police department to reform a broad range of its policies and practices, including those related to sexual assault.

But a May 2014 New Orleans Inspector General Office’s audit of the NOPD’s Uniform Crime Reporting process found that the department was still misclassifying rape complaints at a high rate. In 41 of 90 sex crimes complaints examined by the Inspector General, officers misclassified the complaints and failed to report them to the Uniform Crime Report. The inspector general’s office found that all 41 cases should have been reported as rapes. Instead, 20 were coded as noncriminal “signal 21,” 14 as unfounded, and seven as “sexual battery,” a lesser offense not counted in the UCR as a major crime.

A high-profile sexual assault case from 2014 sharply illustrated the NOPD failures outlined in the inspector general office’s report. In the early afternoon of July 1, 2014, New Orleans resident Maria Treme reported that she was drugged and raped at a popular downtown bar and restaurant. Detective Keisha Ferdinand of the NOPD’s Sex Crimes Unit did not take Treme to a hospital for a forensic exam or toxicology screening until about 8:30 that night; exams and blood tests didn’t begin until 11 p.m. Treme said that she then did not hear from the NOPD about the status of her case for three weeks so she went to a local news outlet to draw attention to the mishandling. Soon after the story aired, Treme claims, Ferdinand scolded her for “making the NOPD look very bad.” The police later said they had lost key surveillance video footage provided to them by the club. In December, when the police discovered the video was missing, they went back to the club and found that the footage had been taped over, in accordance with the club’s video retention policy.

The new Sexual Assault Kit Initiative grants to agencies like the Orleans DA do not address such profound investigative failures. Indeed, Cannizzaro’s office said in 2017 regarding Treme’s case: “The NOPD has neither made an arrest nor have they presented the case to the DA’s office as a non-arrest consult.”

Nor does the funding address a culture within Cannizzaro’s office that involves threatening and even jailing rape victims for refusing to testify as well as publicly mocking sexual assault victims. When rape survivors including Treme held a press conference in front of the Orleans DA’s office in May 2017 to highlight the handling of rape cases, then-DA spokesman Christopher Bowman sarcastically tweeted, “Don’t you hate it when a protest has more reporters than protesters!!!” (Bowman later deleted this tweet as well his Twitter account.)

When asked by The Appeal to respond to criticism that the Orleans DA’s office has mistreated victims of rape and domestic violence, spokesman Ken Daley said that he would not “do that kind of interview over the phone” and ended the conversation.

But in a recent brief filed in support of a civil rights lawsuit against the Orleans DA for jailing a domestic violence victim who was deemed uncooperative, advocacy groups like the Louisiana Foundation Against Sexual Assault blasted prosecutors for a “propensity to distrust and blame the victim and to bully them into assisting the prosecution.”

Treme’s case never made it that far.

“The case was damaged beyond hope,” she told The Appeal, “all evidence was messed with. And collected improperly.”