When My Brother Died Of An Overdose, The State Charged Two People With Murder. That Isn’t Justice.

You can’t incarcerate a public health problem. It doesn’t make us safer. It doesn’t repair harm.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

Seven years ago, I lost my 29-year-old brother to a heroin overdose.

In one breath, my dad told me, “Rob passed away.” The phone fell from my hand and I ran to the bathroom and violently threw up. The next few moments, hours, are impossible to describe. My body seized uncontrollably. I could only repeat the word “no” while my teeth turbulently clattered. My mom hadn’t received the news. Calling her was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. She picked up the phone cheerfully, I told her I had to tell her something, immediately I could hear the fear in her voice. I told her: “Rob is dead.”

The words fell out of my mouth in sync with my body as I dropped to the floor, summoned to my knees by the gravity of the loss of my only sibling. She screamed in agony into the phone, a sound that could only be caused by the pain of a mother losing her first child. I set the phone next to my knees and buried my face into my palms and sobbed while my mom’s repeated screams of “my baby, my baby” polluted the air I was grasping for. I don’t remember a single thing after that. Not until the next day.

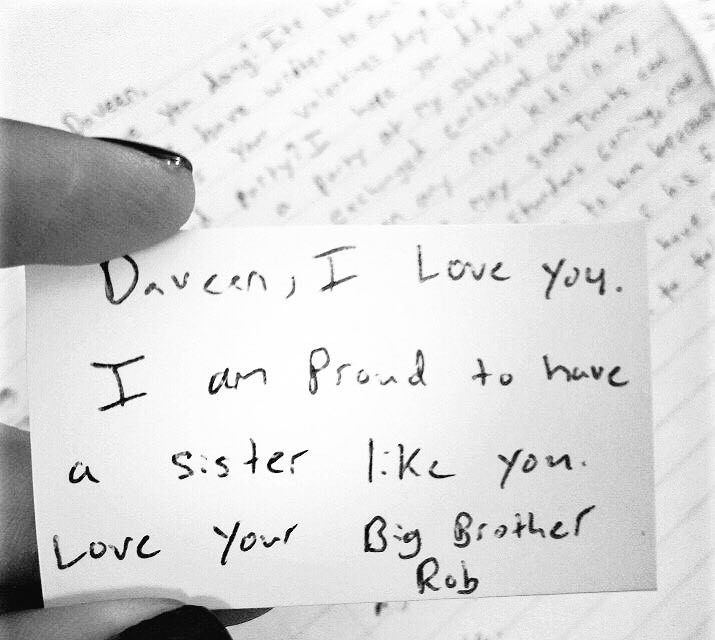

I had to go through all of his things. His clothes, mail, money, drugs, all of it. I found a stack of cards, each of them resting in opened envelopes. I pulled one out to read:

“You’re going to come out the other side. You can do it. I love you forever.” – Mom

Each card was full of encouragement and hope—and an understanding of my brother’s humanity. Bryan Stevenson has said: “each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” I, too, wholeheartedly believe this. My brother was more than the violence. My brother was more than his incarceration. I saw him. In small moments, I saw love and pride. I saw someone who wanted better. I wish I would have told him that more.

When my brother died, the state government charged two people with murder: the man who sold my brother drugs and the woman he died next to. My family fought tirelessly on their behalf. We didn’t want to see two people who needed support and resources jailed. You can’t incarcerate a public health problem. Putting humans in cages doesn’t make our communities safer. Putting humans in cages doesn’t repair harm. My brother was gone. Sentencing other people to be absorbed into a system that is not built for restoration, but for punishment, isn’t justice.

We were ultimately able to help those people avoid jail time. But many more have not been so fortunate. Although the cultural conversation around opioids has been notably different from the conversation around drugs like crack—something that happened, as the “New Jim Crow” author Michelle Alexander put it recently, “not because of newfound concern for people of color who have been the primary targets of the drug war, but because drug addiction, due to the opioid crisis, became perceived as a white problem”—there has still been a familiar, punitive, and racist legal response to the epidemic from all over the country.

Since 2011, according to the Drug Policy Alliance, 39 states and Washington D.C. have passed or enacted legislation to increase penalties related to fentanyl. These harsh, and frankly senseless, laws hurt Black people the most. A 2018 analysis of federal fentanyl sentencing revealed that 75 percent of all individuals sentenced for fentanyl trafficking were people of color, suggesting that fentanyl enforcement already mirrors other disparate drug enforcement.

In the United States, the annual number of overdose deaths has surpassed firearm and car crash fatalities combined. People of color make up 20 percent of deaths involving prescription and non-prescription opioids in the U.S. and that number is growing. When I went through my brother’s things, I found piles and piles of prescriptions for opioids. Many experts believe the rate of deaths among people of color would be even higher if they had the same levels of access to healthcare as white people, like my brother, did.

Our healthcare system has racism at its core. So does our criminal legal system. So, too, do our housing, education, and employment systems. They work in concert with one another to keep poor people poor, and function as systems of oppression against Black, Indigenous, and communities of color. It’s our work to fundamentally dismantle these systems and imagine something new.

My friend Dwayne Betts reminded me recently that there is a profound limit to what facts can communicate. We need poems, songs and stories more than ever. Our reflections are there. Our visions of justice are there. The most personal can also be the most creative and we can use our wounds as our bow. So today, on what would have been my brother’s 36th birthday, I’m telling a part of his story. It is one small story that needs to be told in “the war on some drugs.”

Daveen Trentman is a founding partner of The Soze Agency. Alongside her team, Trentman has led major productions including The Museum of Drug Policy, which has toured in four countries; Truth to Power; and the Right of Return Fellowship, which invests in formerly incarcerated artists. Trentman served as the executive producer and lead curator of the Museum of Broken Windows. She co-curated The O.G. Experience, an art exhibit that exclusively featured formerly incarcerated artists, and was recently awarded a silver Clio Award for experiential events. Influenced by a personal connection to the issue, Trentman has invested in working deeply on campaigns centered on drug policy and criminal justice.