We’ve been fighting the drug war for 50 years. So why aren’t we winning?

A new paper argues that President Johnson’s 1967 Commission on Law Enforcement’s report on the subject was “decades ahead of its time.”

From the ’80s and into the aughts, “drugsandcrime” was one word for politicians. Drugs followed crime, or vice versa, and drug use was rarely discussed as anything other than a menace: “Public Enemy No. 1.” Thanks to an unprecedented uptick in overdose deaths initially affecting white people, that get-tough rhetoric has begun to soften. President Trump has declared the overdose crisis a national public health emergency.

But he isn’t the first president to see it that way. Before Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush turned drugs into a signifier of urban decay, and before Nixon launched his “War on Drugs,” President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 assigned James Vorenberg, future assistant to Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox, to lead more than a dozen legal experts and scholars to examine “every facet of crime and law enforcement in America.” Far from a cohesive system, little was known about how the fragmented patchwork of “law and order” actually worked. Among other accomplishments, the task force helped establish 911 dispatch services across the United States and a procedure governing the treatment of suspects after arrest.

But there was also a short and obscure chapter in the Commission on Law Enforcement’s 1967 report, titled “Narcotics and Drug Abuse” that addressed both the causes and ramifications of illicit substance use. The commission was “decades ahead of its time” on the topic of drugs, Bryce Pardo and Peter Reuter write in “Narcotics and Drug Abuse: Foreshadowing 50 Years of Change,” their paper in the journal Criminology & Public Policy.

The authors, drug policy researchers at the University of Maryland, analyzed the commission’s chapter on drugs—now over 50 years old—with fresh eyes and new knowledge. The Appeal caught up with Pardo to discuss contemporary drug policy, including the use of harsh criminal penalties, the new difficulties posed by illicit fentanyl, and alternatives to prohibition gaining political momentum. Below is an interview edited for length and clarity.

You write that the Johnson administration’s Commission on Law Enforcement was “decades ahead of its time.” What did they get right about law enforcement’s role in drug control back then?

Bryce Pardo: I was really shocked by how they recognized the limits of drug law enforcement. They said even complete control, complete enforcement, won’t eradicate this problem. But they failed to foresee the negative impacts law enforcement could have in policing urban communities of color, and other harm-enhancing aspects of law enforcement.

They were also fairly forward-thinking when it came to [methadone] maintenance therapy. They discussed how we needed to have more research in maintenance therapy, and how the regulations with regard to the Harrison Act [a 1914 federal law that regulated and taxed opiates and coca products] were confusing and limited options for drug users when it came to treating their drug use.

They saw demand reduction as a useful tool to reduce crime. And I think having a law enforcement agency say that today would be shocking to hear, from say, the DEA or something like that. I was surprised to hear that from the ’67 report, coming from the kind of drug war era of the ’80s that I remember. The show Cops on TV, that’s what I grew up with, and to go from that to a commission 30 years before talking about how we need to expand maintenance therapies—that just really struck me as as very forward-thinking.

What derailed the forward thinking in the 1967 report? If the seeds for medical treatment were sprouting back then, why did the drug warriors eventually win out?

If you think about the drug war in terms of today, where you have GIs in SWAT gear kicking down doors and arresting drug dealers in their houses, that was really part of Reagan’s initiative, starting in the early ’80s. Even though Nixon was the first to declare the War on Drugs, he was more comprehensive in his approach, by advocating for methadone and other treatment modalities, along with supply-side interventions.

Cocaine came on the scene and really took off. And dealing with cocaine is just different than heroin. You don’t have any medication; there is nothing you can give a drug user who is addicted to cocaine. When you have new forms of drug use, like freebasing or smokeable cocaine, which hit you harder through that route of administration, it really scared a lot of people and the response was to crack the whip.

It does seem that the orientation of the policy is that, we’re just going to shift the market out of sheer will. They came from kind of a post-lunar landing American phenomenon where if we can put a man on the moon, we can eradicate drugs. You had this emphasis on creating a “drug-free America.” That brought us “Just Say No!” and these kinds of platitudes. Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which Reagan really latched onto, also promoted looking at drugs as a moral failing.

Despite changes in rhetoric, America’s response to illicit drug use still focuses on arrests for nonviolent drug crimes. And many of these arrests are for simple possession. Do you think that this strategy has value?

Arresting drug users doesn’t make sense unless their drug use has become a problem. Arresting a repeat DUI offender or somebody who has broken into a home to pay for his or her habit—there are programs that we could employ that do use the criminal justice system in a more appropriate fashion.

There’s the Swift, Certain, and Fair sanctions or the HOPE (Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation With Enforcement) model. Those types of programs may work. But ideally we’re not arresting the individual for his or her drug use, it’s the actions related to his or her drug use. Clearly, [in those cases] their use of substances has spilled over into problematic territory. They’re committing crimes to pay for their habit, or they’re not using responsibly and they’re engaging in risky behavior in public and putting other people’s lives at risk. So those are when you might step in and use corrective measures.

But, by and large, you’re going to find very few people in the drug policy community who think arresting people for simple possession is a reasonable approach to our drug problem.

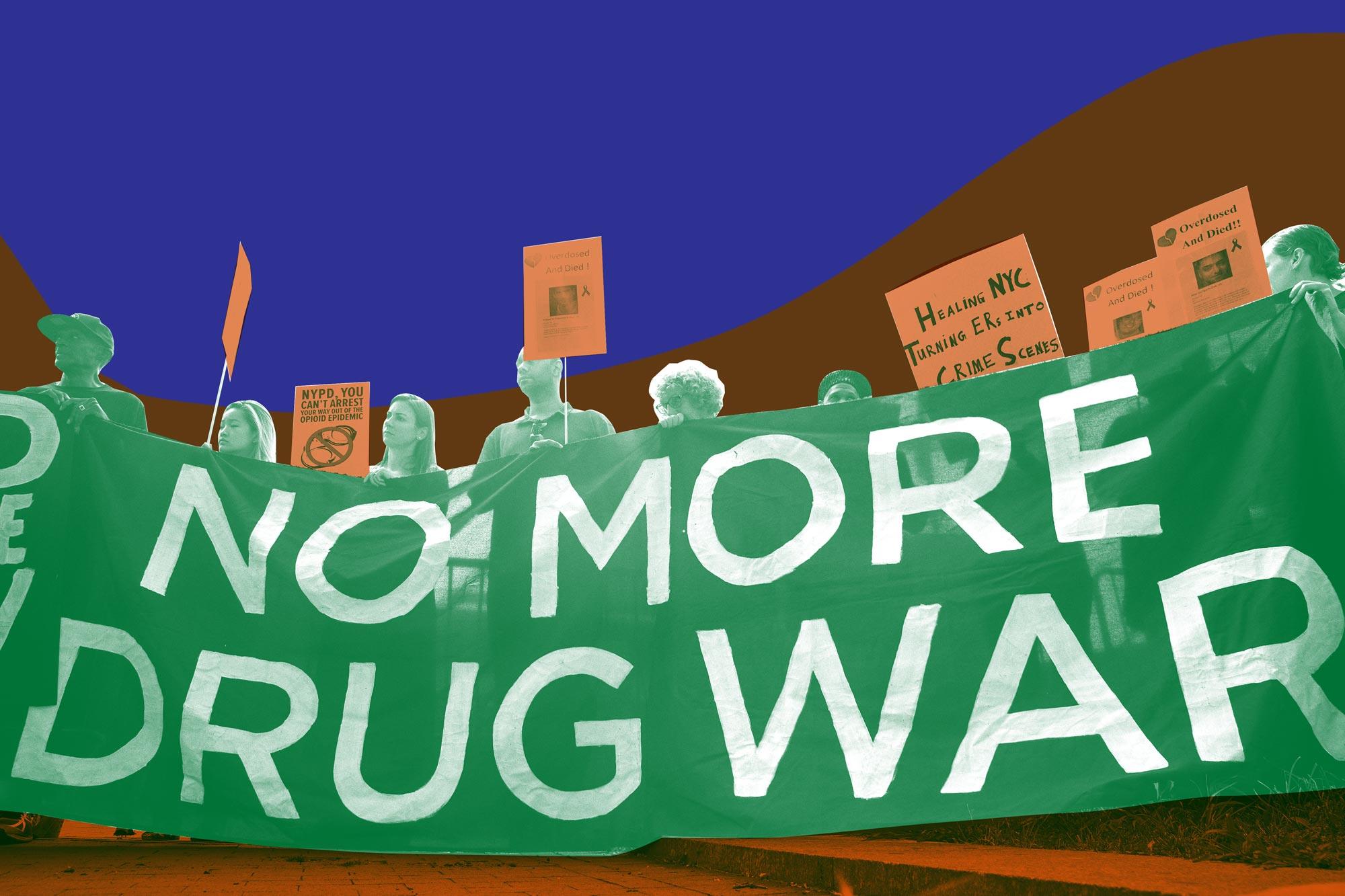

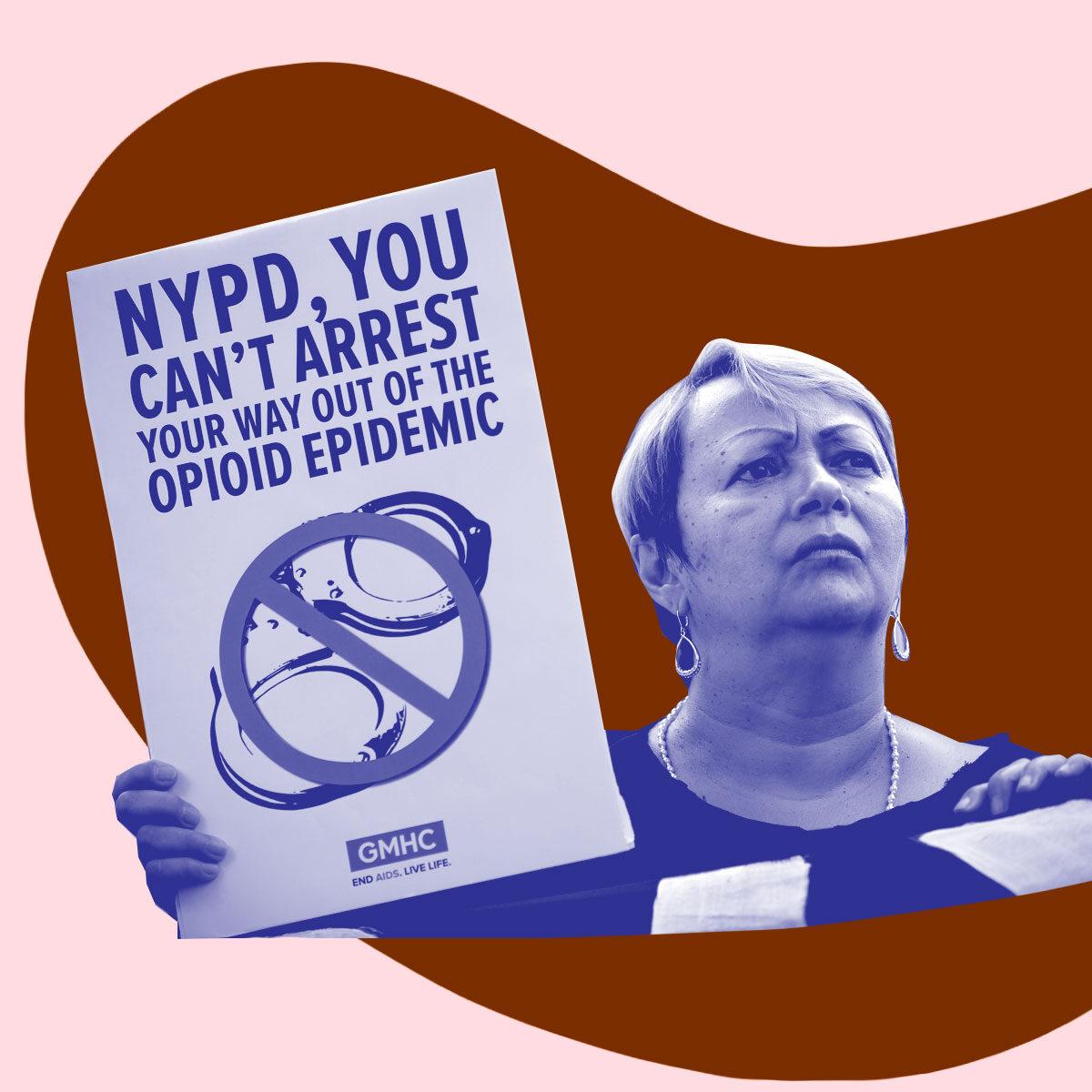

Today, police officers, prosecutors, and politicians often say, “We can’t arrest our way out of the overdose crisis.” But I’ve reported on several cases where a drug user gave a friend a bag and then is charged with manslaughter or murder when that friend overdoses. That’s a very harsh response.

I remember the “we can’t arrest our way out of this problem” taking steam with Obama’s first drug czar. Gil Kerlikowske, former chief of police in Seattle, said this during [President Barack] Obama’s first term. That started to shift the rhetoric at the federal level where people started to realize that we need to do something else.

There’s a signaling effect at the federal level saying we need to do something different. But when it comes to the actual application of the law, most of it happens at the state level. So getting state prosecutors to not charge a user for “social supply” when that individual and his friend or her friend overdoses would be a good step in the right direction. But you’d have to get local prosecutors to buy into that. So they might not hear that message for a while. Now with the new administration kind of shifting the rhetoric back in the other direction, it’s kind of scary because you could have a signaling effect in the other direction.

Do you think the shift in rhetoric, like Trump calling for the death penalty for dealers, is going ramp up harsher enforcement?

Right now, yes. The federal government has a role in terms of kind of framing the debate. After the initiation of the War on Drugs, some say that we had a retreat initiated under Obama. They came out with the Cole Memo, saying we’re not going to crack down on states that are legalizing cannabis for recreational purposes.

The signaling effect has an impact on local jurisdictions and after the Cole Memo came out, you saw more jurisdictions saying we could legalize for recreational purposes. I do think that the shift of the tone away from the criminal justice system for drug users was positive under Obama.

The idea of increasing fentanyl penalties was tossed around prior to Trump—in California and Massachusetts. Some of these include lowering the threshold that trip mandatory minimums for fentanyl. But now some prosecutors are more willing to charge dealers with homicide when an overdose occurs.

DAs and prosecutors, in a lot of cases, are elected. Again, there is this political push to look like you’re doing something about the problem. If there’s a problem with drugs in your community and you’re charging, it looks like you’re doing something versus if you’re not charging them.

What do you think of the recommendations released by President Trump’s commission on opioids?

The recommendations were fine. They were pretty boilerplate. I have commented amongst my colleagues saying that they don’t look at fentanyl very closely. They still see the crisis as a prescription drug problem. It’s true that we need to turn off the tap, and we are doing that with the new prescription guidelines, prescription drug monitoring programs, and with abuse deterrent formulations. But doing that could cause other problems, and it seems to be that it is impacting users’ decisions to move to the illicit market.

However, in this report, they had an opportunity to look at innovative drug policies that focus on synthetic opioids and there’s pretty much zero in there. They do talk about creating new antagonist therapies—stronger naloxone—so that we can save people’s lives who are overdosing on fentanyl. Sure, fine, that’s great. But there’s no innovative approach trying to prevent the overdose from even occurring: looking at supervised consumption sites, heroin-assisted therapy, those types of innovative programs that specifically target the threat from the potency of fentanyl.

They do talk about increased interdiction and detection measures. But, by and large, they missed the mark when it comes to thinking forward about the problem.

Has anything like illicit fentanyl come on the scene before? Have police ever faced a sudden outbreak as big as this?

To this extent? No. Illicit fentanyl and analogs have been around in isolated incidents as far back as 1980. A few analogs would show up in markets, and nobody would know what was going on until they tested the drugs. Transdermal patches were invented in the ’90s, and you’d have diverted transdermal patches where people would suck out the liquid.

Fentanyl had a real big kick in 2006, when a lab in Mexico was producing it and mixing it with heroin. There were a couple of markets in Chicago, Detroit, and a few other places in the Midwest that were hit hard by that. The DEA [Drug Enforcement Administration] and CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] came on real quick and expanded access to naloxone, and the DEA actually did a very good job of shutting down a lab right away.

We haven’t seen a crisis to this extent, where you have drug users looking for traditional drugs like heroin, or in the case of Prince, who’s looking for Vicodin, and getting something that’s orders of magnitude more potent. I don’t think that that has happened, where the users are buying something that’s more harmful and not wanting it. They want what they’re traditionally used to. And it’s happening on such a wide scale.

What I can say, though, is that usually these markets don’t come back down to where they were before. We used to have a morphine problem and then we had a heroin problem. We’re going to be [stuck] with the fentanyl problem, at least in the short term. And that’s really scary.

A study recently came out of Rhode Island, where they found that treating opioid addiction with medications in jail and prisons made a significant dent in the overdose rate. From your perspective, why doesn’t every single jail or prison offer these medications? What’s the barrier here?

My guess is social attitudes. People look at these medications as though you’re trading one addiction for another. If you want to force people into abstinence, it’s probably not going to work. You need to meet their needs. If they get their quality of life back using Suboxone or methadone, who gives a shit? But I think for a lot of people, that’s a hard pill to swallow.

I was really shocked to find out a couple of months ago that states like Indiana and West Virginia have moratoriums [making it harder to license] new opioid therapy providers, and it’s like, why are you fighting this problem with your hands tied behind your back? It’s crazy. You should be licensing as many providers as you can.

Again, it’s social attitudes. The states that are having the biggest problem will probably continue to have the biggest problem until they change the way they think about drug abuse and drug addiction.

There’s obviously a lot of talk about opioids. Maybe too much. You write in the paper that alcohol was curiously left out of the chapter on drugs in 1967, and specifically the way alcohol is connected to violence. Alcohol today kills way more people than opioids. Are we not focusing enough on that?

Absolutely. We are still having a huge problem with alcohol. Alcohol is a factor in an estimated one-third of violent crime, guns, and alcohol-related arrests or violations. Not an insubstantial number of police service calls are due to alcohol, domestic violence, drunk-and-disorderlies or DUIs.

We still have a problem with alcohol, and we’re probably going to have more of a problem now that we’ve reduced taxes. The tax cut law that was passed last year also cut taxes on alcohol. Phil Cook at Duke has been clamoring for increasing taxes. There are projections that if you double the tax, the number of [drunken driving] deaths would drop by more than a third.

I do think the alcohol problem is often overlooked because it’s licit, and because there is a broad user base. Most alcohol users use responsibly, and most drug users use responsibly, too. But most alcohol users are infrequent, and they don’t see any problem in their own social setting, which is fairly safe. So they don’t see any need to increase taxes, and the industry is very strong and protective about not increasing taxes and regulations.

The War on Drugs has been disproportionately waged in minority communities, even though there’s zero evidence that people of color do more drugs than white people. You write that aggressive law enforcement has contributed to a “deterioration in state-community relationships.” What changes need to happen here?

There’s creative solutions to some of these problems. You have people who say legalize everything, and that would solve that problem. But in some instances, it would create problems elsewhere. If we’re not going to legalize, there’s a middling approach, which would be to improve the way we do policing such that it’s more community-oriented. Instead of looking at policing as an occupation, police need to look at it as more of a service that they’re providing. A lot of the rhetoric has changed and a lot of the training has changed.

There’s a lot of room to go. Police are still very quick to the draw. And I think the drug war and the emphasis on SWAT tactics has had a huge negative effect on the way police look at the policed. They look at [the policed] as a potential threat rather than a client. The opioid problem, in some instances, has changed this. Now, police are requested to administer naloxone to overdoses. I’ve heard stories of police being horrible about it and reluctant to do it.

You see that some local jurisdictions are starting to change their tune. Vancouver Police Department has very forward thinking when it comes to harm reduction. They now look at Insite [supervised consumption sites] as part of the package. They request politely for drug users to go and use over there, to spare the public from witnessing public consumption. Nobody wants to see people injecting in the street. Vancouver PD has also been very forward-thinking when it comes to offering alternative agonist therapies. They did a report a year or two ago that said outright that we should try heroin-assisted therapy, which was remarkable for a police department in North America to say.

What are some of the most exciting alternatives to drug prohibition that you have your eyes on?

Part of the problem is that there’s a false dichotomy presented to people, which is legalize or prohibit. And there’s a lot of options in between. A few years ago, Rand put out a report about cannabis in Vermont. They proposed 12 different cannabis policies you could choose from. You can increase prohibition and crack down even more [or you can have] a fully unregulated free market. And between that, they have policies like what we have here in D.C., which is “grow and give.” You’re allowed to grow six plants in your home and give away up to an ounce to anyone over 21—no transaction.

It’s clearly created a gray market. But the gray market doesn’t have some of the trappings of commercialization which some people would like to avoid. There’s the Dutch model, where it’s illegal in back but legal in the front, which means you can sell it retail legally, but you can’t sell it for wholesale. And then there’s a bunch of other opportunities or options in between: So like, creating a state monopoly, creating a public benefit corporation, or nonprofit to distribute—there are a bunch of different options.

There are other things we could do that still keep prohibition but reduce the harms. Portugal has done that. They’ve maintained prohibition, but they’ve essentially reduced the harms of the individual drug user, by removing the criminal penalties for his or her possession or drug use. So now if you’re caught with up to a 10-day supply of whatever drug you have that’s prohibited, you’re referred to a commission made up of a lawyer, a clinician, and essentially a social worker. These three individuals determine what type of user they’re dealing with. If you’re a problematic user, you may be referred to treatment, or maybe get a slap on the wrist and pay 70 euros.

Most users are basically let go with nothing other than a warning and those who are problematic users are referred to treatment. It’s a decriminalized model, but they also include ramped-up treatment provisions and harm reduction tools. At the time, they were facing a heroin crisis much like today.

Several cities are gearing up to open supervised consumption sites, where people can administer their own illicit drugs under medical supervision. Over 100 of these sites are in operation across Canada and Europe. What do you think of that option?

The literature review on supervised consumption is interesting. … There’s been several dozen articles looking at outcomes, several more looking at user utilization, and public opinion. But when you look at the outcomes that we care about, like overdose calls, overdose deaths, crime, improper disposal of injection equipment, that kind of stuff, we see that the majority of the design methodologies are lacking in rigor.

I would say that supervised consumption facilities probably do some good and there’s definitely a moral argument there to be made for allowing individuals to inject without the threat of overdose.

It’s going to take a lot of different solutions and everything on the table is game, I think. The problem is so severe. … There needs to be some sort of discussion in conservative states about health care at-large, you know, just looking at health care more holistically. In addition to that, looking at mental health care and drug addiction care so that we can actually get more opioid treatment providers out there. I think that would be a lifesaver for rural America.

I’ve been trying to get people to consider researching prescription heroin for some users. Especially in today’s market where fentanyl is in the market. I think we better act before it’s too late because eventually there might be a day when the market will completely convert to fentanyl and you will see demand, which is starting to appear in some areas, where people are now saying that they’re hearing drug users looking for fentanyl in the market, they’re not looking for heroin anymore because they’re too tolerant.

We need to start talking about the violence in certain communities in this country. Communities like Baltimore, which has been kind of degraded by drug use for the last 30 years, as well as rural communities, that have more recently been touched by drug overdose as well. We need to try and have this broader discussion without it getting politicized is the hope.

This story was co-published with Vice.