One of Utah’s Best-Known Police Chiefs Has Spent Decades Defending Police Misconduct

Chief Ken Wallentine has repeatedly defended police behavior that judges later found violated the constitution or resulted in millions of dollars in settlements and judgments.

This story was reported by the Utah Investigative Journalism Project in partnership with the Invisible Institute and Salt Lake City Weekly

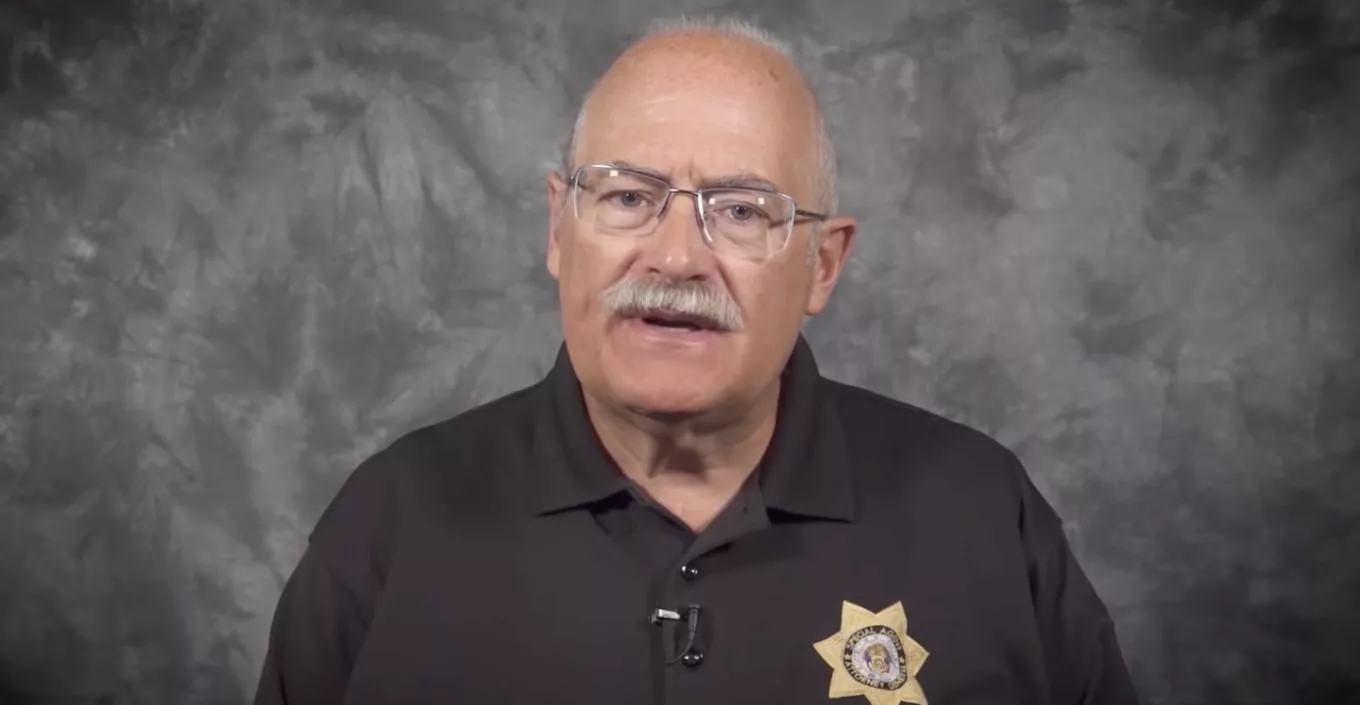

Ken Wallentine is one of Utah policing’s most high-profile figures. He frequently gives testimony to legislative committees considering bills affecting the criminal justice system, and served as president of the Utah Chiefs of Police Association, in addition to his role as chief of police for West Jordan, a suburb of Salt Lake City that is Utah’s third-largest city.

It’s perhaps a natural denouement to a lengthy career in law enforcement, starting as a security guard while a student at Brigham Young University in the 1970s. Since then he’s worked as a city patrol officer, a prosecutor and reserve deputy sheriff in a rural county, and the investigations bureau chief for the state Peace Officers Standards and Training Division, before being named West Jordan’s chief in 2018.

He’s also had a significant hand in shaping police policy and regulation, in Utah and nationwide.

He was hired in the early 2000s to develop a new curriculum for the state’s “entire basic training program,” he once said in a deposition. Street Legal, his guide to criminal procedure, has been published by the American Bar Association since 2008.

He was a former attorney general’s chief of law enforcement, overseeing investigative bureaus and acting as the AG’s “representative to law enforcement executives throughout the state,” he testified, and returned to the office in 2016 to develop its virtual reality training program.

Wallentine also has at times seemed supportive of police reform. He wrote a statement in early 2023 to “unequivocally condemn the circumstances that resulted in the death of” Tyré Nichols, who was killed by five Memphis police officers. He sends officers to trainings that encourage them to analyze their own thought patterns and internal biases, because officers with those skills “are those who can pursue paths of peace,” he told the West Jordan Journal in 2020.

Yet Wallentine also has a well-paid side gig as a consultant and expert witness in which he has faced accusations of working to stymie reform efforts, and repeatedly defended police behavior that judges later found violated the constitution or resulted in millions of dollars in settlements and judgments.

Anti-reform policies with Wallentine’s ‘fingerprints all over’

Since 2010, Wallentine has worked for LexiPol. The private company was founded by a Southern California lawyer and former police officer, Bruce Praet, who decided to go into writing policies to reduce liability for police departments after defending them in misconduct lawsuits in the 1990s.

Wallentine testified in 2015 that LexiPol policies relating to “use of force, firearms, a use of force review board,” and other related topics don’t “go out the door without my fingerprints all over” them. And in a 2013 deposition he identified Praet as his partner in crafting these policies.

During that time period, LexiPol’s use of force policies strictly adhered to what’s known as the Graham standard. This standard is named for the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1989 decision, which set out that police use of force is not excessive if it is “objectively reasonable” given the information available to the officer at the time. It has been criticized for years by legal scholars and police officials who feel it doesn’t go far enough in limiting when and how police can use deadly force.

To LexiPol, encouraging police departments to restrict their officers’ use of force beyond what the Supreme Court requires was contrary to its mission of reducing liability for its clients. Such policies “box officers in,” a 2018 LexiPol white paper co-authored by Wallentine and Praet reads, and are “likely to create — not solve — legal issues for the agency.” The company strongly opposes rules prohibiting officers from actions like chokeholds or firing at moving vehicles.

A review of LexiPol training materials during the time period for which Wallentine’s “fingerprints” were “all over” its use of force policies shows a repeated aversion to pushing officers to de-escalate situations or rethink how to better approach a scene to avoid resorting to violence.

“By producing policies and trainings that are silent on… alternatives known to reduce police violence, Lexipol provides no structure for participating agencies to consider these alternatives,” UCLA law professors Ingrid Eagly and Joanna Schwartz wrote in a 2022 article titled “Lexipol’s Fight Against Police Reform.” (The company contested some points in the article in an undated, unsigned blog post.)

Wallentine and Praet have even gone so far as to reject “use of force continuum,” policies which provide the progression of options that officers should go through before resorting to deadly force. Praet referred to the concept as “hogwash” in a 2016 webinar, and in a 2013 deposition, Wallentine went further. “I would never draft a policy that has a use of force continuum in it,” he said. LexiPol’s current Use of Force Policy Position paper still rejects continuum standards.

Wallentine also endorsed a LexiPol policy that encouraged officers to use a lack of English proficiency as one factor to determine reasonable suspicion to investigate whether a person is undocumented. When the policy was called unconstitutional by the ACLU of California, Wallentine was dispatched to defend the company to the Los Angeles Times.

LexiPol’s policies for California changed after a law was passed in 2017 barring police from cooperating with immigration enforcement, but in 2019, a review of the equivalent policies in other states by The Appeal showed the language still existed.

Wallentine was also closely tied to LexiPol’s backing of “excited delirium,” a concept with racist roots commonly used to defend police killings, including those of George Floyd, Elijah McClain, and Brian Cardall, a Utah man who died after being Tased in 2009 by Hurricane police.

Medical professionals questioned the theory for decades, but until last year, LexiPol explicitly endorsed the concept.

As recently as 2019 Wallentine gave a webinar on protocols developed by the Institute for Prevention of In-Custody Deaths. He is certified as an instructor in excited delirium investigations by the institute, a for-profit Nevada company co-founded in 2005 by an attorney for Taser to help defend the stun gun manufacturer against claims that its weapons were deadlier than advertised. Wallentine also sits on the institute’s board of directors.

In 2022, LexiPol removed the phrase “excited delirium” from its model policy after it was disavowed by most mainstream medical groups. Even so, all of the language describing the condition still exists.

LexiPol has also begun to distance itself from Praet, while maintaining use of his policies.

In October 2017, a year before he was appointed chief in West Jordan, Wallentine stepped away from his role overseeing policy for LexiPol to one he still has today, writing a regular column about the law and policing for its publication Police1. Shannon Pieper, LexiPol’s senior director of marketing and content, wrote in an email that “Chief Wallentine is a part-time employee with Lexipol focused on writing and speaking engagements. He does not have a direct role in developing Lexipol law enforcement policy content.” She did not respond to follow-up questions.

Wallentine’s side career: Justifying police misconduct

In addition to his work in writing policies and interpreting police obligations under Supreme Court precedent at LexiPol, Wallentine has also pursued another side career as an expert witness consultant in police use of force and other misconduct lawsuits. In all but one of dozens of cases, he was hired to produce a report exonerating police actions.

The Utah Investigative Journalism Project and Invisible Institute identified a total of 77 cases, ranging from 2002 to several that are still pending, for which Wallentine served as a police expert witness.

Those cases include 25 where a person died at the hands of police or in police custody — plus a miscarriage allegedly caused by police negligence.

He’s defended police actions in overturned wrongful convictions in Phoenix and Kansas City, alleged excessive force from police K9 bites in Las Vegas and suburban Los Angeles, in-custody deaths in Charlotte and the Navajo Nation, and fatal shootings everywhere from tony suburbs of Chicago and Santa Barbara, to rural Northern Utah and a highway outside Nashville.

In depositions, he’s said that both LexiPol and the Utah Attorney General’s Office either discouraged or outright barred him from testifying on behalf of plaintiffs suing law enforcement. In any case, multiple plaintiffs’ attorneys interviewed said that they viewed him as being part of the policing world’s “cottage industry of exoneration,” as a 2021 New York Times investigation termed it.

Cases for which he’s worked to defend police officer or department actions have resulted in over $37.5 million being paid out to plaintiffs, either through settlements or jury awards, according to a tally of federal and state court cases by the Utah Investigative Journalism Project and Invisible Institute. (Another $650,000 jury award was later overturned on a technicality; there are also six settlements the news organizations could not obtain amounts for.)

That includes $10 million that an Iowa jury awarded in 2013 to Jarvis Boggs, who was paralyzed at 18 after a Waterloo police officer responding to a potential burglary crashed into his car while speeding through an intersection without lights or sirens on (the actions of a “reasonable and well-trained officer,” according to Wallentine’s report).

In another Iowa case, the city of Cedar Rapids settled for $8 million in 2021 with Jerime Mitchell, a Black man paralyzed during a traffic stop by an officer who had killed a man during a traffic stop just over a year prior. It was reportedly the largest police misconduct settlement in the state’s history. In this case, Wallentine was hired by the city, which reportedly spent another $600,000 defending the officer in court, only to fire him for dishonesty in his reports about the shooting.

Other seven-figure settlements and judgments in cases for which Wallentine was hired to produce a report exonerating police actions include:

- A $2 million settlement with the family of Brian Cardall, the Utah man whose 2009 death after being Tased by Hurricane police officers on the side of the highway prompted a statewide conversation about mental health training for police. The officers’ decision to Tase Cardall twice as they tried to stop him from running into traffic nude was reasonable, Wallentine wrote, because Cardall was suffering from “excited delirium,” which the officers had been properly trained to respond to with Tasers. A federal judge found that Cardall was at best a “nonthreatening misdemeanant” who was not resisting arrest and did not warrant a use of force being used against him.

- A $3.2 million settlement with Robert Swofford Jr., a Florida man who was critically injured by Seminole County Sheriff’s deputies in 2006 after he exited his house with a handgun to investigate a disturbance on his property — which turned out to be the deputies pursuing a burglary suspect. Swofford’s “decision to go into his field, armed with a handgun was unreasonable and negligent,” Wallentine wrote. A federal judge disagreed, finding that “every reasonable officer… would conclude that the use of deadly force against Mr. Swofford was unlawful.” The decision was upheld by a panel of appellate judges.

- A $2.45 million settlement with the mother of Sariah Lane, a 17-year-old who was shot in the head in 2017 by then-Mesa, Ariz. detective Michael Pezzelle, during an ill-advised police maneuver to bring an acquaintance of hers in on domestic violence charges. Officers boxed the car in and fired into it when they thought her acquaintance was reaching for a gun; no gun was found in the car. Wallentine argued that “a reasonable and well-trained officer” would have taken the same actions.

- A $1.3 million settlement with the mother of Gregory Thompson Jr., an unarmed Black man who was killed after a Lebanon, Tenn., officer claimed he tripped while approaching Thompson’s car, accidentally firing his weapon and prompting the other officer to fire fourteen times, killing Thompson. The second officer’s decision to open fire was “the only force option,” Wallentine wrote in his report.

In each of these cases, settlements were reached after judges rejected police department claims that they or their officers should be afforded qualified immunity. Under this judicial doctrine, plaintiffs must prove that officers violated a “clearly established” constitutional right and that the officers knew or should have known that their behavior was unconstitutional, which experts say can be prohibitively difficult. In many instances, plaintiffs must find a near exact copy of their case with a favorable ruling in the same federal circuit.

Despite this strict limitation, federal judges in 24 of the cases in which Wallentine was hired by the defense rejected qualified immunity and found plaintiffs had legitimate grounds to argue that their “clearly established” constitutional rights were violated. In another six cases involving Wallentine, a federal district court judge or an appellate panel found that qualified immunity should be denied, but was contradicted by another judge elsewhere in the process.

In six Wallentine cases where qualified immunity was denied, juries still found in favor of police.

By contrast, judges in 15 cases granted police qualified immunity. There is no data about police expert witnesses and how their findings compare with the ultimate outcome of cases.

When qualified immunity is denied, “it’s often because there are factual disputes that a jury needs to decide,” said Schwartz, the UCLA law professor. If the plaintiff successfully argues that a constitutional violation of a “clearly established right” may have occurred, “then it should be for the jury to decide,” she continued.

Wallentine also has a mixed record in state-level cases he’s been hired on. The Orange County, Fla. Sheriff’s Office asserted a “stand your ground” defense in a state court lawsuit over the fatal shooting of William Charbonneau, who was having a mental health crisis, in suburban Orlando.

In that case, the state judge found in 2019 that Wallentine’s argument — that Charbonneau, while lying prone on his lawn, could have flipped around a shotgun that was pointed at his own head to shoot at the deputies within a “fraction of a second” — was “not credible based on common sense, physiology, and physics.” That case later settled for $125,000.

William Ruffier, who represented Charbonneau’s widow, said it was an “extraordinary finding.” Considering the span of his three-decade legal career, over which he’s argued many police use of force lawsuits in the Orlando area, Wallentine’s testimony “was just so off the wall.”

“Obviously, he was paid a bunch of money to render an opinion,” Ruffier said. “And that’s what he did.”

Wallentine has also made arguments that police department officials had exercised proper oversight over rogue officers, in clear contradiction with other evidence.

In 2005, a lawsuit alleged that South Salt Lake Officer Gary Burnham had raped a 19-year-old, and claimed that the SSLPD was negligent for allowing Burnham to continue working after both of his ex-wives filed criminal charges alleging domestic violence and rape, sexual conduct while on duty, and sexual assault of one of their children.

Not so, Wallentine argued, finding that the SSLPD had thoroughly investigated the claims, which “did not give notice to the SSLPD of any probability of future misconduct of the nature claimed in” the lawsuit, and dismissing the claims of Burnham’s ex-wives as “largely unsupported.” Wallentine also noted that Burnham’s “ecclesiastical authority” had “spoke highly of him” during the hiring process, and that a polygraph showed that he “held traditional values.”

On the contrary, federal Judge Clark Waddoups took issue with SSLPD’s investigations into Burnham’s ex-wives’ allegations, finding that investigators never attempted to interview women whom Burnham had allegedly had sexual contact with while on-duty — despite having enough information to locate them. Then-SSLPD Chief Theresa Garner even testified during her deposition that she believed the allegations against Burnham constituted a pattern, but did nothing to increase supervision before he raped the teen.

Because a “reasonable jury” could find that South Salt Lake “showed deliberate indifference” to the allegations against Burnham, Waddoups found the same “reasonable jury could conclude that South Salt Lake showed deliberate indifference to the sexual misconduct of its officer,” and ruled that he could not dismiss the lawsuit, which settled for $125,000 five months later. POST has since decertified Burnham.

In 2007, two Kansas City, Mo. officers allegedly caused Sofia Salva, a Sudanese woman, to have a miscarriage by denying her medical care during a traffic stop. Michael Lyman, a former police investigator in Kansas and Oklahoma hired as an expert by the woman’s lawyers, found a ten-year pattern of officers not being punished for ignoring requests for medical attention, or injuries that clearly required medical attention. Lyman came to this finding by analyzing over a hundred internal investigation files.

Wallentine countered that police officials could not have possibly known that officers needed additional training on when to provide medical assistance by cherry-picking 13 cases he claimed undercut Lyman’s report. Andrew Protzman, the Kansas attorney who represented Salva in the case, said that Wallentine “basically disregarded” the actual training practices of the department in order to place the blame solely on the officers. The case later settled for $750,000.

“Mr. Wallentine just misses the purpose”

A recent case, not related to use of force, has raised questions not only for plaintiff’s attorneys about the quality of Wallentine’s legal analysis, but also for a local defense attorney as to whether Wallentine fully understands his own police department’s legal obligations.

Wallentine was hired to defend the Phoenix Police Department’s role in the wrongful conviction of Frances Salazar, a grandmother who was convicted in 2016 of drug possession based on testimony from an officer with a history of dishonesty — a history which was hidden from Salazar and her attorneys.

Then, six months after she was convicted, the Maricopa County Attorney’s office quietly filed a disclosure of what’s known as Brady material, based on a 1963 Supreme Court decision that requires information that would be favorable to criminal defendants to be provided to them.

The disclosure related to a Phoenix Police internal investigation that found the officer had been dishonest — a finding directly relevant to his testimony at Salazar’s trial. The investigation had substantively concluded months before Salazar’s trial, but the disclosure wasn’t filed until six months after — because, city attorneys claimed, there was still a pending appeal process.

Prosecutors didn’t notify Salazar’s attorneys of the filing, so it sat unnoticed for months until they consulted the docket to prepare for her appeal. They immediately filed a petition to have the conviction vacated, which was granted within a few months. By then, Salazar had spent nearly two years in prison.

In 2019, Salazar sued the city and prosecutor’s office over the violation and the loss of nearly two years of her life to incarceration. Wallentine was hired by the Phoenix police to produce a report explaining why the department had no obligation to ensure Salazar’s attorneys knew about the officer’s Brady material, and that its policies on the topic were in compliance with Supreme Court holdings.

He found that the officer had complied with Phoenix’s policy, and shifted blame to the prosecutor’s office to notify the police that their policy was deficient. Besides, he claimed, “there is no generally accepted standard for timeliness of transmission of potential Brady information,” and suggested that Salazar’s defense attorneys should have been filing public records requests for this material.

In an excoriating decision released in September 2022, a federal judge dismissed his opinions — they “simply mirror City Defendants’ arguments and do not establish that police officers’ obligations under Brady are superseded by office policy” — and instead upheld what repeated Supreme Court and U.S. Court of Appeals opinions have found: that the responsibility to turn over Brady material is that of the government as a whole, down to the individual police officer, and not limited to the prosecutor’s office or department officials setting policy.

“The evidence shows that there is little, if any, training provided by the PPD regarding Brady requirements,” the judge, who rejected the city’s claims of qualified immunity, wrote. “Deposition testimony showing that a veteran police officer and the Chief of Police exhibit little understanding of officers’ obligations under Brady supports that there is a lack of training about Brady requirements.” The city has appealed the decision.

Wallentine’s opinion shows that he, too, may not have a full understanding of a police department and officer’s obligations under Brady, according to an expert.

“You have to remember that Brady is a rule about protecting a criminal defendant’s right to a fair trial,” said Ann Marie Taliaferro, an attorney with Brown Bradshaw & Moffat in Salt Lake City who handles criminal defense and post-conviction cases, in an interview. Wallentine’s statements “that there’s no set timeframe, or process for how Brady information is supposed to be disclosed — that’s not true, because the whole purpose is to get it to the defense in time that they can use it effectively at trial.”

Wallentine’s report is centered around his “fundamental belief that the police and prosecution are separate,” Taliaferro said. While that may have once been true on some level, “that idea is certainly not true for Brady purposes. They’re one and the same.”

In her view, the allegations of untruthfulness should have been disclosed to Salazar’s defense attorneys as soon as they were made. “If you have allegations against a police officer for making false reports, or making a false arrest, or being investigated [for those], that’s favorable information” that needs to be disclosed under Brady, she said.

Wallentine’s assertion that the defense attorneys should have filed a public records request is “beside the point” — Brady is an obligation on the government to affirmatively turn over documents. “I really respectfully think that Mr. Wallentine just misses the purpose” of Brady, Taliaferro said.

It’s not surprising to her as a Utah criminal defense attorney; she rarely gets information that should be affirmatively disclosed under Brady from any prosecutor’s office or police department — West Jordan included — unless she asks. “A lot of the time, we’re talking with other fellow defense attorneys” to keep tabs on officers with histories of misconduct, she said.

Tauni Barker, a spokesperson for West Jordan, said in an email that “The City of West Jordan is in full compliance with Brady requirements.”

It’s not clear if West Jordan, which pays Wallentine over $200,000 a year, is aware of the extent of his work as an expert witness. On city disclosure forms, required by his employment agreement, he only writes that he engages in “occasional short term consulting.” He has consulted on at least 17 cases since beginning work at the city.

Meanwhile, his consulting fees have increased from $125 an hour “for all activities outside of court testimony” and $500 a day for travel to Western states, plus $250 an hour for court testimony, in 2007, to a flat $300 an hour fee with travel fees ranging from $1,200 to $1,750 a day in 2022.

In lieu of a response to requests for comment and a detailed list of questions sent a week before publication, Wallentine responded through West Jordan spokesperson Tauni Barker that he was on family leave and unavailable for an interview.

Barker also declined to make Mayor Dirk Burton available for an interview, but wrote in an email that “the City of West Jordan requires employees to disclose outside employment. This policy, adhered to by all employees, including Police Chief Ken Wallentine, helps maintain transparency and accountability. Updates are required when there are changes in outside employment, and disclosures are reviewed in cases where a potential policy violation has occurred.” She said that Wallentine’s “disclosure has not been flagged for any potential policy violations” in response to a follow-up question.

She provided a statement from Mayor Dirk Burton, which read, “We are incredibly fortunate to have Chief Ken Wallentine leading the West Jordan Police Department. Under his fantastic leadership, our department has achieved remarkable success, maintaining staffing levels and fostering an exceptional workplace culture that prioritizes equity, inclusion, and policing with an outward mindset. Chief Wallentine’s extensive experience and dedication to public safety, exemplified by his numerous accomplishments, make him an invaluable asset to our city.”

In response to questions about the cases and criticisms raised in this story, she wrote, “Regarding questions about whether the city is aware of individual cases that the Chief has been involved with on his personal time, I would refer you to the original response provided. In particular, I would call out the Chief’s efforts in investing in a culture that prioritizes equity, inclusion, and policing with an outward mindset.”

Todd Macfarlane is a Kanosh attorney who opposed Wallentine while representing the family of Brandon Eric Chief, who was killed by West Valley City police in 2010. He said Wallentine’s mindset, in his experience, is centered around finding the evidence to justify police actions, no matter how egregious their conduct.

Macfarlane, who clerked with Wallentine for a Utah appellate judge early in their careers, continued, “He’s one of those guys [whose] worldview is that law enforcement officers, as a general rule, can do no wrong.”

“Truly, in my view, the way he is hardwired is to always look for and find the evidence that will support the law enforcement position.”