Commentary

Virtually No One is Dangerous Enough to Justify Jail

A common sense cost-benefit analysis of pretrial detention.

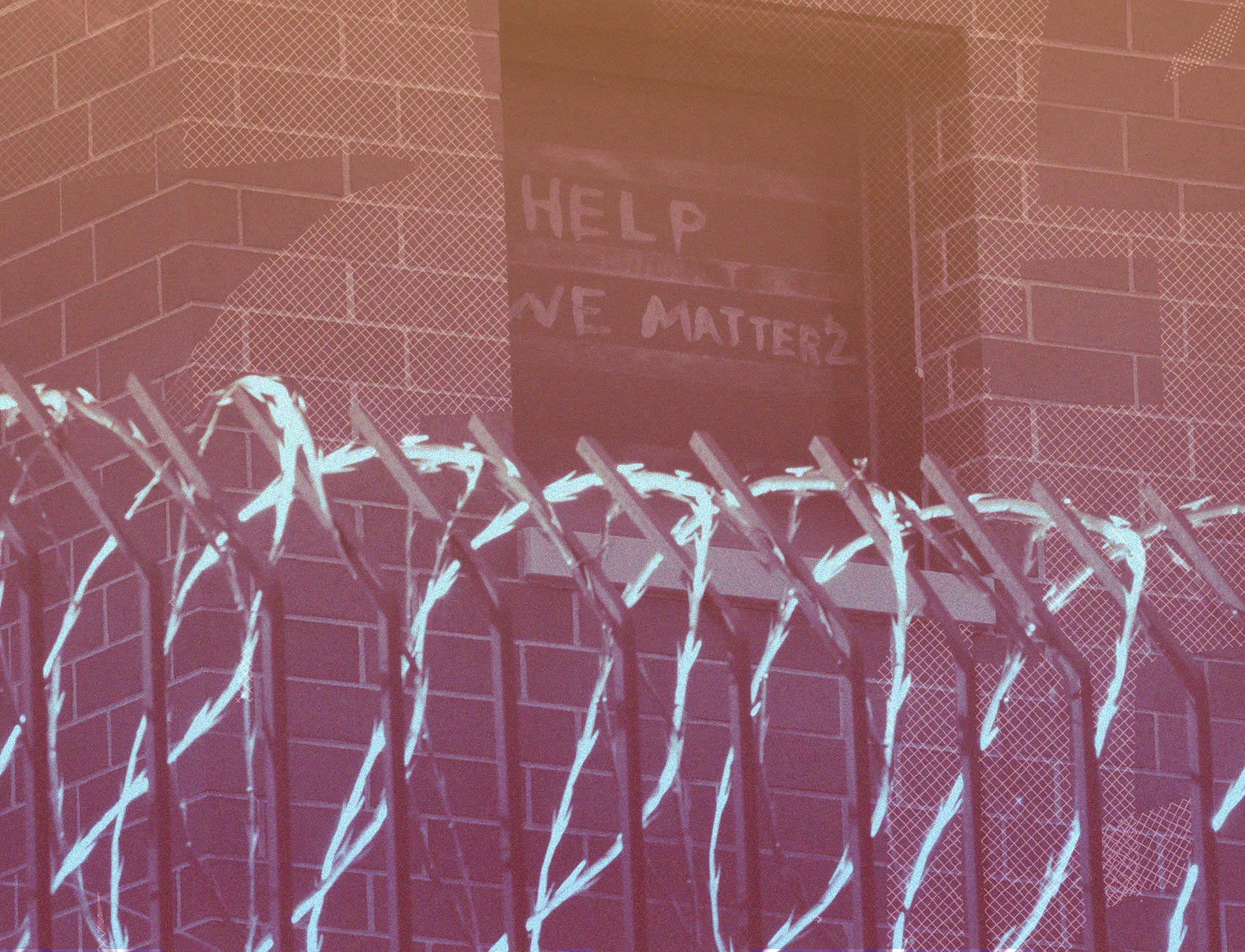

Every day, jails in the U.S. hold close to half a million people who are legally presumed innocent. When people who have been arrested can’t afford or are denied bail, they are locked in concrete cages that are sometimes littered with excrement, often subject to extreme heat or cold, always rife with disease and violence, and always steeped in humiliation, distress, and fear. In recent years, one-fifth of the incarcerated population hasn’t even been convicted of a crime.

The stated rationale for most pretrial detention is public safety. Current law authorizes detention (or unaffordable money bail) if the accused person presents a threat. Supreme Court doctrine suggests that the threat must be grave enough to outweigh the defendant’s right to liberty. Yet there has been no serious attempt to figure out how “risky” a person must be for detention to be justified on these grounds.

We conducted a survey study to help answer that question. And we learned that, if you ask people to consider the harms that both crime and jail inflict as if they themselves could experience either one, their answer is clear: Jail is rarely justified as a means of harm prevention.

To explain the study, let’s return to the legal justification for pretrial detention (or unaffordable bail). Once upon a time, flight risk was the principal concern in the pretrial phase. In today’s interconnected world, however, few people pose a true risk of flight. Nowadays, the primary justification for keeping accused people in jail is to prevent a future crime. Remember, though, that we are talking about people who have not been convicted. The government has no right to impose punishment before a conviction. It does not claim that pretrial detention is deserved. The legal rationale for detention is simply that its safety benefits outweigh the harm that it inflicts. The public good outweighs the individual cost.

So how dangerous must someone be for the benefit of detention to outweigh its costs? If we detain people who pose a 10 percent risk of committing a serious crime during the pretrial phase, we expect to avoid one serious crime for every 10 people we detain. Is it worth it? This question is extremely uncomfortable, but there is no getting around it.

The benefit of 10 detentions, in economics terms, is the “averted cost” of the crime that doesn’t happen. The primary cost of a crime is the harm it inflicts on the victim. On the other side of the balance, the primary cost of detention is the harm it inflicts on detainees. To figure out whether the averted cost of one serious crime outweighs the cost of 10 detentions, you have to compare the harms of crime victimization and incarceration.

If pretrial detention is justified when it produces a net social benefit, it should be exceedingly uncommon. Instead, the opposite is true.

The standard approach to this kind of cost-benefit problem is to quantify the relevant harms in monetary terms. But quantifying things in dollars can be distorting, because the meaning of a dollar depends on your financial status.

We took a different approach. We conducted a survey asking people to compare the harms of crime and incarceration directly, imagining themselves as both crime victim and jail detainee. We asked questions like, “If you had to choose between spending a month in jail or being the victim of a robbery, which would you choose?”

The results showed that people are incredibly averse to being incarcerated. Respondents deemed a single day in jail to be as bad as being the victim of a burglary; three days in jail to be as bad as a robbery; and a month in jail to be as bad as experiencing a serious (nonsexual) assault. These responses were not just uninformed speculation. Nearly a third of our sample reported that they or a loved one had been incarcerated. Another third reported that they or a loved one had been the victim of a crime. The median responses in each of those groups, as well as in the group that reported experience with both incarceration and being the victim of crime, were almost identical to the median responses overall.

If jail is as harmful as our respondents judged it to be, only a very high probability of averting serious crime can justify pretrial detention. On average, we would have to avert crimes as grave as burglary in order to justify jailing someone for a single day, avert crimes as grave as robbery in order to justify jailing them for three days, and avert crimes as grave as serious assault in order to justify jailing them for a month. It might be justified to jail people with a 50 percent likelihood of committing a serious assault within two weeks if we limited the pretrial detention to two weeks, because we would expect to prevent one serious assault for every two detentions—that is, for every month of detention.

The problem is that it is extremely hard to predict serious crime. Even our best predictive tools are nowhere near accurate enough to identify individuals who pose a 50 percent chance of committing a serious crime within two weeks. Validation data for one common risk assessment tool, for instance, shows that, among those classified as high-risk for violence, the expected rate of violent offending within one month is 2.5 percent. If we detain all members of this group, we expect to avert five violent crimes for every 200 monthlong detentions. According to our median survey respondent, that would impose harm 40 times greater than the averted harm of five assaults.

What the survey suggests is that pretrial detention is almost never justified on the cost-benefit rationale that current law and policy proclaim. Because incarceration inflicts profound harm and our powers of prediction are limited, the cost of detention generally outweighs its expected benefits. If pretrial detention is justified when it produces a net social benefit, it should be exceedingly uncommon. Instead, the opposite is true.

So far, the dialogue around bail reform has centered on process: Should we get rid of cash bail? Should we replace it with actuarial risk assessment? These debates are secondary; they focus on methods rather than standards. Eliminating monetary bail does not necessarily wind down detention rates if judges can simply order detention instead. Nor do risk assessment tools.

In the 1987 case United States v. Salerno, the Supreme Court wrote that preventive pretrial detention must be a “carefully limited exception” to the norm of liberty. To make it so, we will need laws that set a clear standard for detention (or bail that results in detention). The laws should stipulate when a person is dangerous enough to detain: What probability of what kind of harm over what timespan is sufficient to justify locking a person up for the public good? Even if a person does present a threat that justifies some restraint, detention is not justified in cost-benefit terms unless no less-restrictive intervention can adequately reduce the risk. In almost all cases, there should be methods of harm prevention that do not require total confinement—and that are more likely to have enduring positive effects than throwing people in jail. In addition to standards for detention, we will need accountability measures to ensure that the standards govern in practice.

For too long, we have allowed the pretrial system to inflict tremendous harm in the name of the public good. As is true throughout the criminal justice system, that harm has disproportionately befallen people who are Black, brown, and poor. There may be some cases—cases of acute danger—where pretrial detention is necessary and justified. But given the damage that jail itself inflicts, those cases should be few and far between.

Sandra Mayson is a visiting assistant professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey School of Law and an assistant professor of law at the University of Georgia School of Law.

Megan Stevenson is an associate professor of law at University of Virginia School of Law.