Universal Basic Income Is A Path To A More Just Economy. One California City Is Already Seeing Positive Results.

The pandemic is making it clear that it’s time to radically rethink the social contract.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

The pandemic is forcing a national conversation about what millions know in their bones: most Americans teeter on the brink of financial ruin. Pre-crisis, 40 percent could not afford a $400 emergency, and 43 percent were experiencing income volatility, where annual pay fluctuates 25 percent or more. This prevents financial planning, debt reduction, and saving, while also locking people out of safer products and interest rates. Before the recession, retail and restaurant shift work predominated these trends. But as inequality grows — so does contingent labor, and uncertainty, is now part and parcel of life in the formerly salaried workforce. While freelancing offers flexibility, it comes at the expense of benefits and stability when shocks — like the pandemic — occur.

Although inequality continues rising, our safety net fails at keeping pace. Instead, we’ve witnessed retrenchment of corporate responsibility for benefits alongside sharp increases in gig work. These new dynamics, the uneven exchange between owners and laborers, do not illustrate inevitable market failures. They reflect policy choices about what we value, and it’s time for radically rethinking the social contract.

The umbrella of recurring cash-transfers represents one path towards a more just economy. This includes a guaranteed income, which contains fixed monthly amounts, a basic income covering essential needs, or a universal basic income for all. As evidenced by Andrew Yang’s Presidential run and bipartisan support for stimulus payments, momentum for cash-transfers continues building. While this resonance seems new, it’s an idea with deep roots in our Democracy. In the 1700s Thomas Paine began advocating for dividends, while guaranteed income was the subject of Dr. Martin Luther King’ Jr.’s final book. More recently, the congressional “cash squad,” comprised of four women of color, started pushing for federal cash proposals while cities explore empirically-driven pilots.

The Stockton Experiment

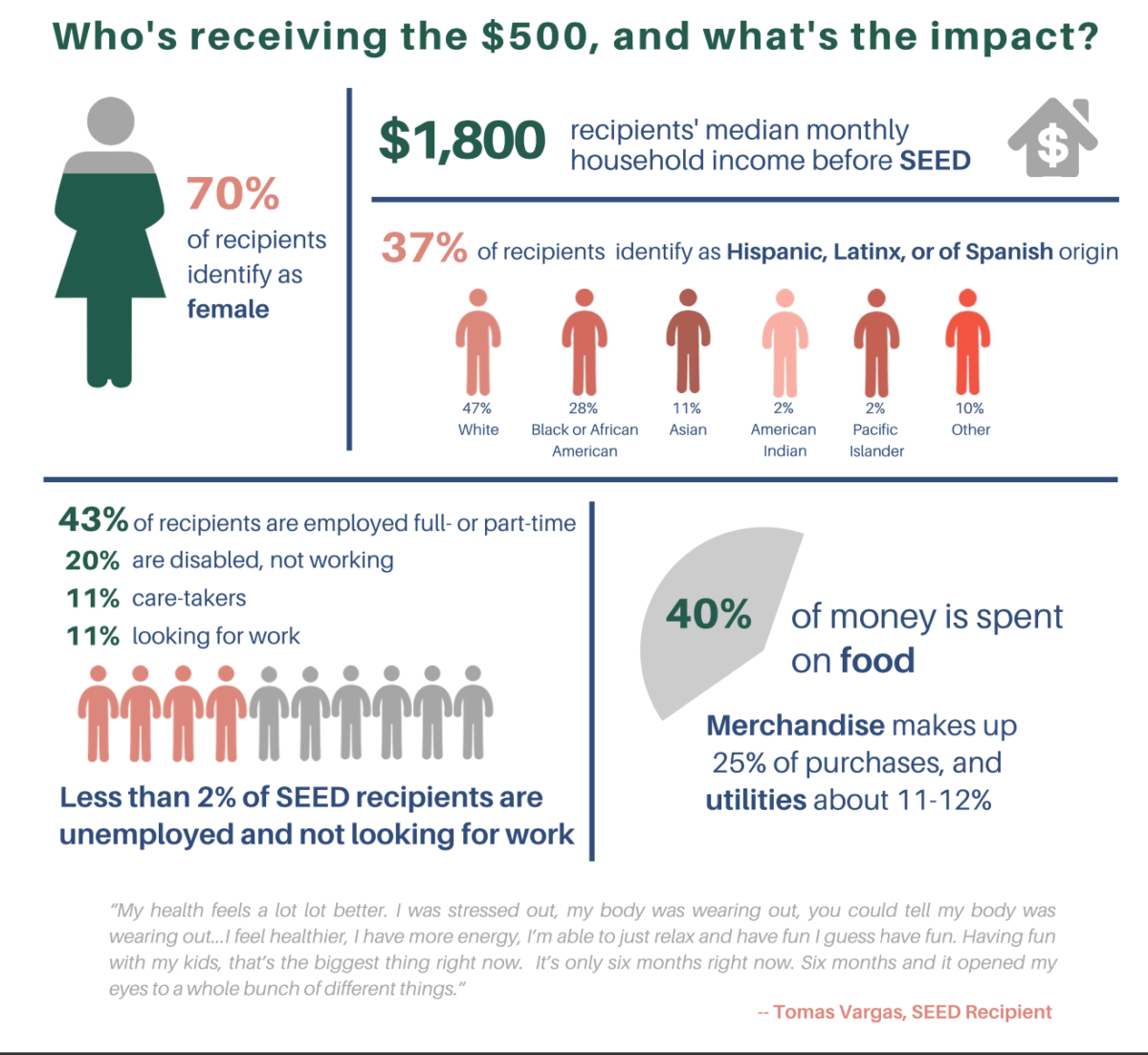

In 2019, the people of Stockton, California, once the foreclosure capital of the US, embarked on a guaranteed income experiment. Last year, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED), began giving 125 randomly selected households, living in census tracts at or below the median income of $46,033, $500 per month via debit card — no strings attached. As a philanthropically funded micro-pilot, no tax dollars are used. The experiment is designed for understanding how a predictable floor may help households weather emergencies, pursue health, and create time for re-imagining alternative futures. SEED asks, if we remove the drumbeat of financial stress, what kind of employees, partners, parents, or neighbors will people be?

Early Spending Data

Despite research demonstrating financial savvy among lower-income families, many still believe lack of restraint causes poverty. This argument doesn’t rest on facts, but on stereotypes of poor mothers and Black women that helped the 1990s welfare reform movement exacerbate structural discrimination through policy. Black women do not make up a disproportionate share of welfare recipients because they do not work hard. Rather, it’s due to systematic exploitation and lack of resources. Overwhelmingly, SEED spending data, seen here, shows recipients spend the $500 on basic needs. Other times, they leverage it in ways returning dignity, like Mekie who purchased shoes for her kids and sent her son to football camp, or this Dad sharing, “[I] paid off PG & E and got my daughter a dress… she got to go to prom. Like a normal teenager.”

Simple logic underpins SEED. First, people are the experts on their own lives. A large body of data shows that, contrary to popular belief, those surrounding the poverty line are savviest at stretching household finances. Second, cash is flexible and needs are dynamic. While families struggle with utilities one month and unexpected illness the next, traditional programs offer zero flexibility for meeting elastic needs. Third, it took hundreds of years to generate inequality in America and remediating it requires multi-pronged policy approaches. A guaranteed income replacing Medicaid or food stamps will not resolve these issues; it recreates them. For this reason, SEED is designed to work alongside existing benefits — not in place of them.

Pandemic Spending Data

COVID-19 has laid bare market failures, especially for the Black and Brown people holding up our economy. We’ve tracked the $500 during the pandemic and found that many shifted the money for ensuring survival. The elasticity of cash created financial bandwidth traditional means-tested programs cannot. Spending on food and household goods rose sharply when the pandemic approached. Food spending in March peaked at 46.5 percent of all overall tracked spending, a nearly 25 percent increase over SEED’s monthly average, and a full 36 percent over March 2019. In Lorrine’s words, “The SEED money has allowed me to purchase food for my family, so I had enough when the pandemic hit. It’s only 500 dollars, but it does make a big difference to a single mother supporting a family. It allows my kids to eat.” Money used for transportation also shifted, as Virginia shared about her son, an essential worker, who was then able to use public transportation, saying, “The SEED money has helped pay for the gas that I need to take my son to and from work every day, which is the only time I leave the house.”

The Way Forward

The financial difficulties associated with at-home parenting, terminations, and working from home shared by SEED participants represent windows into American life. Conventional wisdom dictates we’re to have three months of savings for emergencies, but due to rising inequality few did — and apparently, few corporations did either. More people filed for unemployment in March and April than during the Great Depression. The CARES Act provided a modest $1,200 stipend to many, but not all. Bipartisan support for stimulus payments offers hope, but payments need to match the scale, scope, and duration of the crisis. In this, we look toward what we’ve learned from SEED. First, we must preserve existing benefits like health insurance, food stamps, and Supplemental Security Income to protect the most vulnerable. Second, we must provide recurring cash transfers to workers facing the most risk — and who we now count on to save us. Third, we must realize this window of opportunity, a moment in history for reimagining a more just trajectory.

Amy Castro Baker, PhD, MSW is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the School of Social Policy and Practice and serves as the Co-PI of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration under Mayor Michael Tubbs.

Stacia Martin-West is an Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee College of Social Work. She is the co-PI of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, the first modern city-led guaranteed income experiment in the US.