Undercover Providence Police Faked Withdrawal Symptoms and Solicited Suboxone

Rhode Island prosecutors charged nine people with felony distribution of the addiction treatment drug. Reform prosecutors in other states are declining such charges and instead encouraging access to the drug.

On Nov. 18, Sammy Walker says he was approached in Providence, Rhode Island’s downtown bus plaza by two men, one of whom said he was sick from opiate withdrawal and needed a strip of Suboxone to combat the symptoms. Walker, who is undergoing treatment for opiate addiction, was familiar with what the man said he was experiencing. “You lose all your energy, you can’t move around,” Walker said. “All you are thinking about is, how am I going to get this sickness away, take it away.” One of the men asked Walker if he had any Suboxone, and Walker––who has a prescription for the opioid-addiction treatment drug––sold him a single Suboxone film for $5.

A few weeks later, on Dec. 7, Walker was arrested and held without bail. The men he had sold the Suboxone film to were Sean Lafferty, an undercover detective in the Providence Police Department’s narcotics and organized crime bureau, and a confidential informant. Walker, 56, who has three children and eight grandchildren, spent Christmas in jail before taking a plea—a four-year suspended sentence and nearly $1,000 in court costs.

The official police report for the arrest corroborates Walker’s account in part, saying that Lafferty approached Walker and “indicated to Walker that he wanted one strip, which Walker was selling for five dollars.” The report does not mention the presence of a confidential informant. The police department declined repeated requests for comment, citing an ongoing investigation, and denied a public records request for Lafferty’s body camera footage of the arrest. The ACLU of Rhode Island is filing a lawsuit on behalf of the requesting reporters to obtain the footage.

Walker is one of the thousands of Rhode Islanders who have been prescribed buprenorphine—the generic name of the opiate in Suboxone—to treat opioid addiction. Prescriptions for the treatment have increased significantly in Rhode Island and nationwide over the past three years as experts embrace the drug as the best treatment. As public health experts work to increase access to the drug in communities ravaged by the opioid crisis, local prosecutors are confronting how, if at all, to prosecute diversion of the lifesaving treatment to another person.

Walker was one of nine people arrested in the bus plaza in early December for allegedly selling less than $35 worth of Suboxone strips to undercover police officers. Many of the people charged sold just one or two strips for as little as $3.

The police officers called the sweep “Operation Bussed Out,” and announced on Dec. 9 that they had charged 23 people in connection with narcotics trafficking in the city’s public bus plaza, all of whom allegedly sold controlled substances to undercover police officers.

“The arrests announced today are the result of months of high-quality work through our exemplary Providence Police Department and let the world know that these crimes will not be tolerated in our community,” Mayor Jorge Elorza said in a joint press conference with the police department on Dec. 9, in which mugshots and names of all 23 people charged were presented on a poster and republished in a number of local media outlets.

Although the police said “deadly narcotics,” including fentanyl, had been seized in the operation, none of the police reports from the arrests mention any of the defendants possessing or distributing fentanyl.

Daniel Peterson, who was also arrested and charged with distributing the schedule III narcotic, similarly described being approached by a man saying his friend was getting sick and needed Suboxone, which he provided for a few dollars. (The police report from Peterson’s arrest says that he was walking around the plaza, asking people if they wanted to buy a Suboxone strip, a claim that Peterson denies.) “I was just trying to help him out,” Peterson said, who is also a recovering addict being prescribed Suboxone. “You all help each other when you’re together.” The other seven defendants arrested for allegedly selling Suboxone could not be reached for comment.

Using drugs like Suboxone to treat opioid use disorder is now considered the most effective way to fight addiction. “The use of medications to treat opioid use disorders is shown to have a mortality impact: It saves lives,” said Dr. Daniel Alford, the director of the Clinical Addiction Research and Education unit at Boston Medical Center.

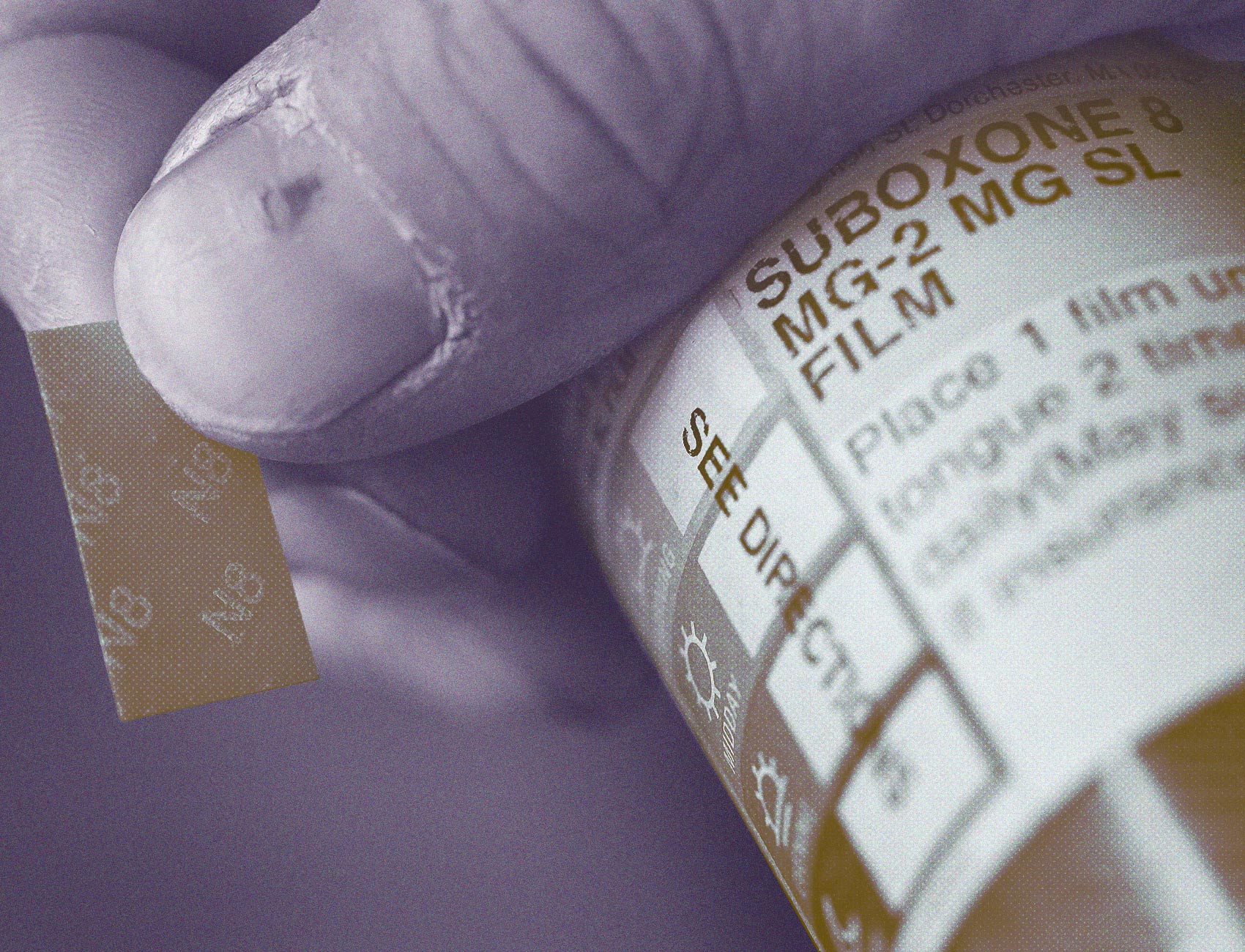

Suboxone combines buprenorphine––a partial opioid agonist, which acts to suppress withdrawal symptoms and cravings––with naloxone, an opioid blocker. Alford says naloxone is combined with the buprenorphine to prevent abuse of the drug, limiting any euphoric high if crushed and injected. As a result, Alford says, “There are some people who would say that diversion––selling buprenorphine on the street––isn’t such a bad thing,” because it might prevent people from using opiates such as heroin or fentanyl. However, he said, using the drug without the direction of a medical professional may not be safe, because buprenorphine can be deadly when mixed with other drugs or when used by people who don’t have a tolerance for opioids.

Studies have shown that most diverted buprenorphine is used to self-medicate, not for misuse, Alford said. A 2019 literature review from the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment found that most people surveyed “used illicit buprenorphine to treat their opioid withdrawal symptoms, either because formal treatment was not available or because the cost of [medication assisted treatment] was prohibitive.” Rhode Island launched a strategic plan in 2014 to increase the number of people on buprenorphine and double the amount of doctors approved to prescribe the drug. Rhode Island was also one of the first states to provide Suboxone to incarcerated people.

Despite these efforts, deeply embedded stigmas around addiction or a lack of health insurance still prevent people from seeking the advice of medical professionals, and instead, lead people to buy Suboxone on the street, says Linda Hurley, president of CODAC Behavioral Healthcare the state’s largest nonprofit outpatient provider for opioid treatment. “If I have been facing discrimination, then I’m not going to be willing to take the risk to get help,” Hurley said.

In June 2017, Sarah George, the state’s attorney in Chittenden County, Vermont, announced that her office would no longer prosecute possession of buprenorphine. It instead would collaborate with local advocates and medical experts to “flood the community with this drug,” George said. In George’s jurisdiction, Vermont’s largest county, opioid overdose deaths dropped by 50 percent the following year, even as they rose in other parts of the state.

Before the drug was decriminalized, a strip of Suboxone on the street cost five or six times more than a dose of heroin, George said. “So if people had the choice, for the money,” George said, “they were going to take the heroin. And they were dying, because all of this was happening right around the start of fentanyl being in people’s heroin.” George said she didn’t understand why the drug had been criminalized because doctors were telling her “this is a drug we want people to use.”

Following George’s lead, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner announced in late January that his office would no longer prosecute buprenorphine possession. Philadelphia has the highest opioid overdose rate of any major U.S. city, and saw 1,116 opioid overdose deaths in 2018—more deaths than those resulting from the AIDS crisis in any single year in the city.

“Nobody wants bupe diversion. Nobody wants to have illegally traded drugs in this gray area regarding medication-assisted treatment,” Krasner told The Appeal. “But we don’t take every problem in society and turn it into a jail cell.” Krasner said that prosecutors should “care a little more about whether people survive their addiction, rather than caring about some headline that they are tough on crime.”

When the cases from “Operation Bussed Out” reached the Rhode Island attorney general’s office, however, state prosecutors arraigned each defendant for distribution of a controlled substance, requested that the judge hold many defendants without bail, and asked for no-trespass orders to the state’s public bus terminal. Six of the nine defendants who allegedly sold Suboxone spent Christmas in prison, held without bail.

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha said that while he had not reviewed the facts of each case, he was concerned about the existence of a “black market” for Suboxone. “Reasonable minds can differ, I suppose, as to whether we’re handling [these cases] appropriately. But I don’t think the answer is to let a thriving black market drug market exist” at the bus plaza, Neronha told The Appeal. He added, “Do I agree that everybody in the state who needs Suboxone should have it? Of course, of course I do. But, you know, we’re left with the hand that we’re dealt with, and we have to address it as best we can.”

Asked about how they would have approached the “Bussed Out” suboxone arrests, Krasner and George condemned the style of policing and prosecution.

“That is appalling, frankly, that that happened,” George said upon hearing that undercover officers had solicited Suboxone from people with prescriptions.

“I see no value in having undercover officers simulate people who are dealing with the agnony of addiction, coupled with withdrawal, going out of their way to purchase individual doses, or a couple, doses of Suboxone at a time for four or five bucks and then locking people up,” Krasner commented. “What’s the point?”

To Walker, the consequences of the arrest are severe. Walker, who had been sober for nearly two years before the arrest, lost his room in the sober house where he had been living for 18 months. After being released from prison, Walker entered an inpatient recovery program in Providence and plans to become trained to be a peer recovery specialist. “These are real people’s lives,” Walker said of Operation Bussed Out. “We are just trying to do the right thing, living right.”