Two Major Victories For A Public Health Approach To The Overdose Crisis

Criminalization as a response to the overdose crisis can cost lives.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

On Wednesday, a federal judge ruled that a Philadelphia nonprofit’s proposal for a safe injection site—a facility where people can use drugs under medical supervision—does not violate federal law. The decision came in a lawsuit brought by the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. The judge’s decision, a close reading of the Controlled Substances Act, concluded that Congress did not have and could not have had supervised injection sites in mind when drafting the law. Furthermore, “the ultimate goal of Safehouse’s proposed operation is to reduce drug use, not facilitate it,” he wrote.

The decision is an enormous victory for the groups advocating for a site in Philadelphia, and for advocates around the country. As Christopher Moraff wrote in Filter: “October 2 will live long in US harm reduction history.”

Safe injection sites, also known as safe consumption or overdose prevention sites, are already in operation in 10 countries. Their purpose is to prevent overdose deaths. Drug users bring drugs to the centers, have access to clean and sterile equipment, and then use drugs under the supervision of trained medical personnel who are on hand, with life-saving equipment, in the event of an overdose. Thus far, there have been no reported overdose deaths at any safe injection site in the world.

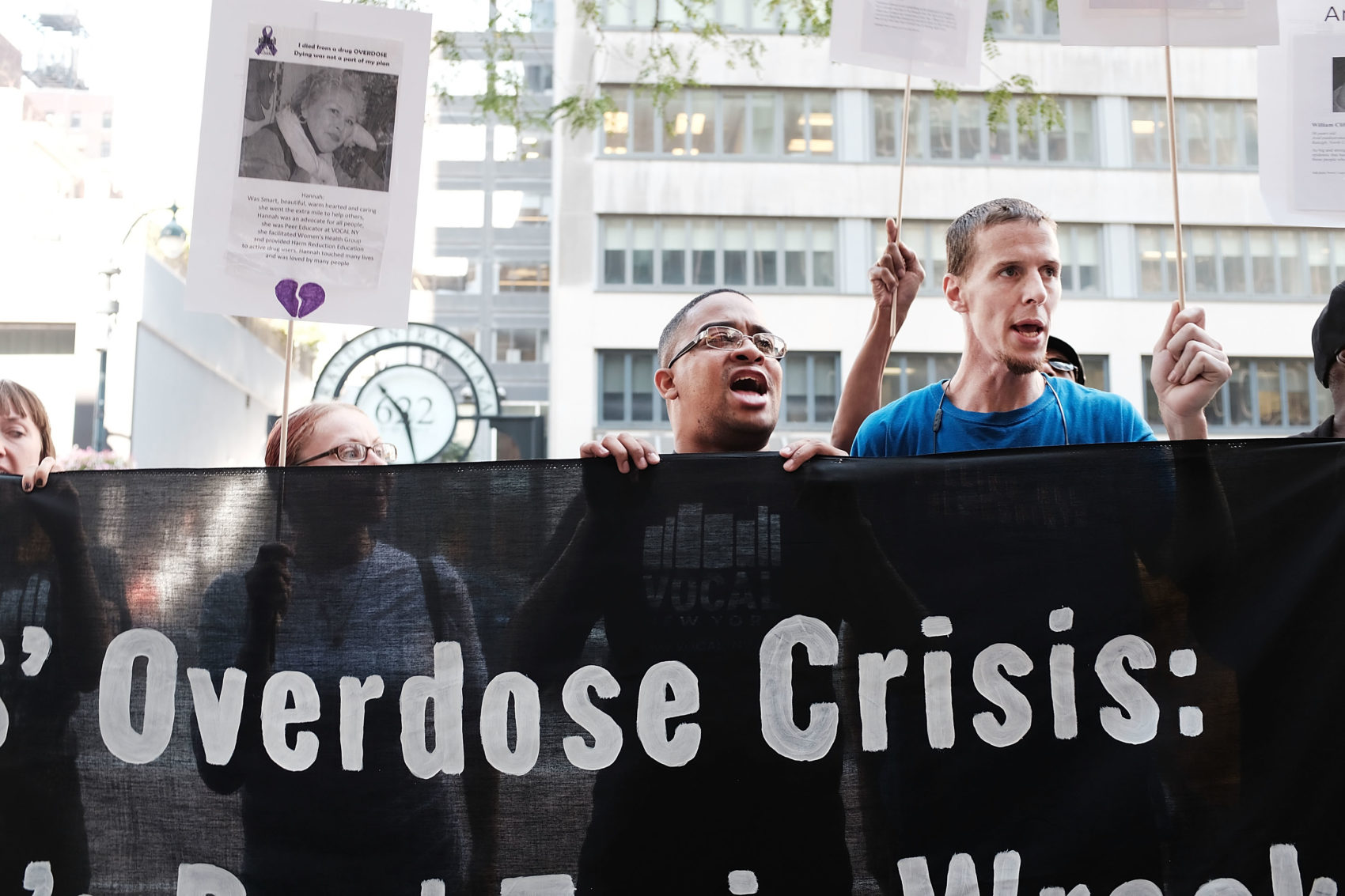

More broadly, the decision is a win for a public health approach to the overdose crisis. There have been thousands of overdoses in Philadelphia alone. About 1,100 people died in 2018, according to reporting by the Associated Press. More than 200 of the deaths were in the neighborhood of Kensington, the proposed location for the supervised injection site. On the day of arguments in the case in August, “Loved ones propped photos of more than a dozen young people lost to the opioid crisis against the outside of the federal courthouse in Philadelphia,” the AP reported.

Nationally, the overdose crisis has taken hundreds of thousands of lives; there were 68,000 deaths last year. That number, despite being slightly down from the number of overdose deaths in 2017, was still, as the New York Times reported, above the “nation’s peak annual deaths from car crashes, AIDS or guns. (The slight dip in overdose deaths from 2017 appears to be entirely attributable to a drop in the number of overdose deaths linked to prescription opioid painkillers.)

In the policy responses to the ongoing overdose crisis, there has been a contest between the criminalization reflex—the belief that every social problem can be solved with handcuffs, jail, a prison sentence—and efforts to move forward in ways grounded in public health research and principles.

The punitive response has been led by the federal government at the highest levels, with rhetoric streaming out of the White House about sentencing people to death for selling drugs and the Justice Department pushing for prosecutions and resisting solutions such as supervised injection facilities. At the state and local levels, there has also been an alarming increase in prosecutions for overdose deaths.

Unscientific and fearmongering responses to the overdose crisis have also included misinformation about fentanyl exposure, the criminalization of pregnant women who have substance use disorders, and opposition to an array of promising efforts like needle-exchange programs, medication-assisted treatment in communities and in jails and prisons, and safe injection sites.

As Abby Goodnough noted in the New York Times in February, in reporting about the Justice Department’s lawsuit against Safehouse, the objections to safe injection sites “are similar to those made against needle exchanges when they first began opening several decades ago, though exchanges now generally have strong support as an evidence-backed tool for reducing disease and death.” Reporting on the closure of a needle-exchange program in Charleston, West Virginia, last year, Josh Katz observed that “public health experts now find themselves relitigating questions that in their view were settled decades ago, while political leaders worry that harm reduction—that is, mitigating the risks from drug use—means enabling drug use.”

But there has also been movement on the public health side of the ledger. Multiple cities and jurisdictions have declared their interest in opening supervised consumption sites and are exploring the possibility. The decision in Philadelphia last week will only strengthen those efforts. In Massachusetts and Maine, federal judges have required jails and prisons to offer treatment to people in custody.

On Friday, Massachusetts’s highest court also issued an important decision, striking down a homicide conviction for an overdose death. The court vacated the involuntary manslaughter conviction of Jesse Carrillo, obtained after the death of Eric Sinacori, to whom Carrillo had sold heroin. Through its decision, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court issued a welcome corrective to the wave of overdose-related prosecutions in the state, and around the country

An amicus brief filed in the case laid out the ways in which prosecutions in overdose deaths run entirely counter to overdose prevention efforts and how prosecutions like Carrillo’s would endanger Massachusetts’s other, effective investments in preventing deaths. It was filed by the Committee for Public Counsel Services (which was representing Carrillo), the Health In Justice Action Lab at Northeastern University, and the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

The brief’s authors wrote: “The bottom line is that prosecuting people who use and share drugs is at cross-purposes with Massachusetts efforts to fight stigma and help people who use drugs emerge from the shadows to make healthier choices. As a result, more rather than fewer lives are at risk.”

The decision by no means ends these prosecutions around the country. In Philadelphia, the fate of the supervised injection site is not settled. But in the contest over how to respond to the overdose crisis, last week’s decisions give hope that a public health and harm reduction approach can ultimately prevail.