Two Cops Said They Saw A Man Grope Women. The Women Disagreed. The DA Charged Him Anyway

An 11-month prosecution of a ‘forcible touching’ case in Manhattan sharply diverges from the office’s treatment of Harvey Weinstein, defense attorneys say.

One night in March 2017, two NYPD officers, Peter Cassidy and Manuel Silva, were patrolling the Times Square area when they became suspicious of a Black man they saw walking around. His eyes “were down” and he was “looking at people’s waistlines,” one said. The officers claimed they then saw him touch three women’s buttocks. They arrested him and interviewed the three women. But there was a problem with the officers’ allegations: The women said they didn’t feel anyone touch them inappropriately.

Still, the cops were determined to press charges.

The man, who requested anonymity via his attorney to avoid reputational damage, asked the officers how they could arrest him if one of the women was saying that he didn’t “do anything.”

“Doesn’t she have to press some charges on me?” he implored, as he secretly recorded the conversation. One officer said, “I don’t care what she says,” and began questioning him on the spot, asking, “How long you been out here for?”

The man’s phone, now in police possession, kept recording. In the audio, one officer seems to tell another that he tried to persuade one of the women to go along with an arrest. “I told her ‘this guy, this guy’s trying to get into your purse,’ just so she could get a little too … And she wouldn’t, she wouldn’t bite. She wouldn’t bite.”

Undeterred by the women’s refusals to implicate the man, police charged him with “sexual abuse in the third degree,” and “forcible touching” of one of the three women. The forcible touching charge carries up to a year of incarceration and the sexual abuse charge carries up to three months. The cops had no cooperating witnesses and did not attempt to find surveillance footage to corroborate their claims. Later, one of the officers even said in court that he had made his observations of the defendant from 100 feet away with “a lot of traffic of people walking by.”

Despite these weaknesses, the Manhattan district attorney’s office chose to take the case, putting the man through an 11-month ordeal, which ended with his acquittal in February.

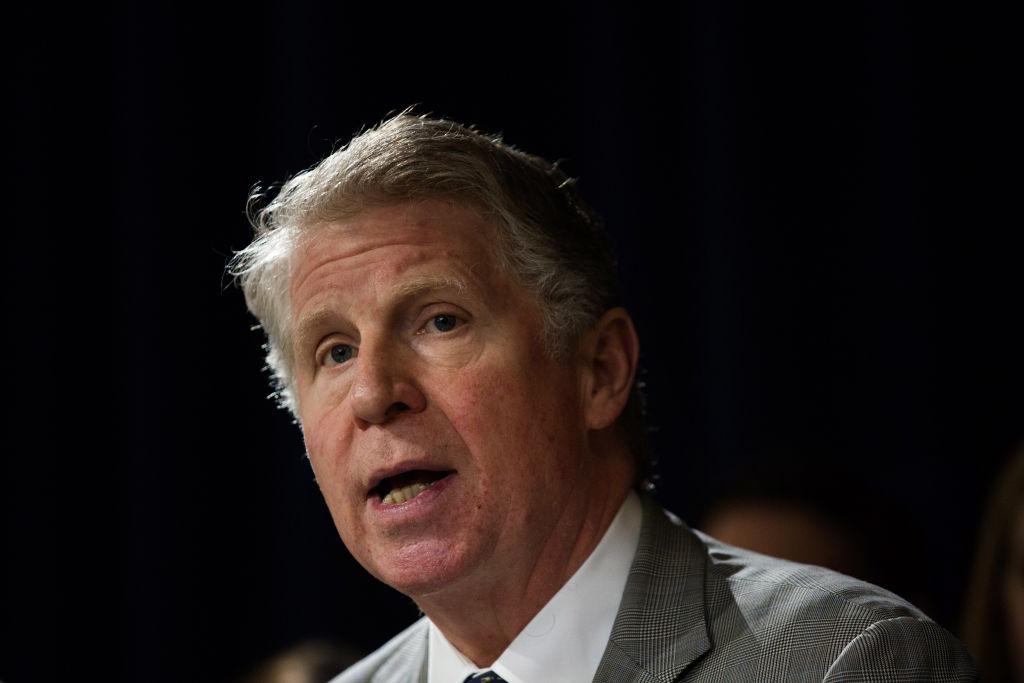

Defense attorneys and legal experts argue that the case points to the disparate treatment defendants can receive at the hands of the Manhattan district attorney’s office. Last year, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance came under criticism after news broke that his office had declined to press the same charges against former film producer Harvey Weinstein in 2015.

In the Weinstein case, unlike this one, a woman actually told police that she had been touched without her consent. The woman even wore a wire, which caught Weinstein saying “I won’t do it again,” when confronted with the allegation. Yet the Manhattan district attorney’s office declined to file charges, claiming it could not prove criminal intent in the allegation because the touching took place when the two were discussing her becoming a lingerie model.

In the Times Square case, the Manhattan DA argued that such criminal intent could be “inferred from the circumstances of the crime.” To make this inference, they relied on Sgt. Cassidy’s claim that the man followed behind a woman for a block and then intentionally touched her.

The DA’s seemingly contradictory decisions in these two cases does not surprise Eliza Orlins, a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society’s criminal defense practice in Manhattan.

“I’ve seen countless cases that have been prosecuted on far less than what Vance decided not to go forward on Weinstein with,” said Orlins, adding that prosecutions without cooperating witnesses are fairly typical in her experience. Had it been one of her clients, rather than Weinstein, who admitted to touching someone’s breast on a recording, Orlins argued that prosecutors would have inferred criminal intent.

Data provided to The Appeal by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) show that in 2017, the Manhattan DA was responsible for a disproportionate 46.5 percent of total convictions in cases where forcible touching was the top charge. Across the five boroughs, 933 cases were resolved where forcible touching was the top charge, of which 490 led to a conviction. Prosecutors declined to prosecute just 24 of these cases citywide. There were only 40 cases disposed where sexual assault in the third degree, a lower offense, was the top charge. The statistics represent just the tip of iceberg, as the charges can accompany more severe charges like felony assault and thus do not show up in DCJS data.

The accused man’s lawyer, Andrew Stengel, a former Manhattan prosecutor himself, argued in a phone interview that the case should have never gone to trial. “The two people who matter most denied that my client touched them,” he said. “From a prosecutor’s point of view, I don’t see how the case could have been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Jocelyn Simonson, an associate professor at Brooklyn Law School, told The Appeal: “The discrepancy between the two cases reveals the presumption of truth-telling given to police officers, where in parallel circumstances a complainant is not necessarily believed; and the presumption of innocence given to more privileged, well-resourced defendants, whereas a less privileged person who is arrested on police officer testimony alone is often presumed guilty.”

Arrest numbers point to substantial racial disparities in who gets arrested for misdemeanor sex offenses like forcible touching. Citywide, 41.1 percent of individuals arrested for these offenses were Black, even though just 24.4 percent of New Yorkers identify as Black, according to arrest data published by the New York City Police Department.

The district attorney’s office said it could not comment, because the case was sealed after the man was acquitted at trial. When asked about the Weinstein case the office declined to comment.

At trial, Stengel was able to undermine the officers’ credibility as witnesses, thanks, in part, to the audio recording the client made during the arrest. Under oath, Sgt. Cassidy claimed that police never asked the accused man any questions after his arrest. The audio plainly disproved this assertion. It also showed that he had to ask if he was being arrested and had, at that point, not been read his Miranda rights.

Furthermore, during a cross examination, Officer Silva seemed to omit key pieces of information about what one of the supposed victims had told him after the arrest. Under oath, he admitted that one of the women told him she didn’t want to cooperate with the police, but didn’t recall the fact that she had also told him she didn’t feel that she was touched.

The man was eventually acquitted of all charges, and is now suing the officers, New York City and NYPD for false arrest; malicious prosecution; emotional distress; negligent hiring, training, and supervision; Miranda violations; intentional infliction of emotional distress; and other violations.

Though the outcome was favorable in this case, defense attorneys argue that defendants without extreme wealth or influence could be saved the stress of unnecessary cases if the Manhattan district attorney’s office were to hold equal charging standards for all defendants, regardless of their wealth or connections.

“The Manhattan DA could choose not to go forward on cases with scant evidence, no witnesses, no video, no property recovered,” Orlins said. “It speaks very clearly to the two-tiered justice system: The poor get one form of justice, and the rich get another.”

If you are a current or former Manhattan District Attorney’s Office employee, please contact us with tips. Reporters George Joseph and Simon Davis-Cohen can be reached on the secure phone app Signal at 929-282-2471 or by email at gmjoseph@protonmail.com or s.davis.cohen@protonmail.com. If you want your messages to be end-to-end encrypted or set to disappear, create a free Protonmail or Signal account to send a message.