For Trump, There Is No Policing Without Violence

A president who openly endorses police brutality struggles with a nation rejecting it.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

Over the weekend, as massive protests against police violence unfolded in cities across America, President Trump watched from the White House and worked himself into a howling, bloodthirsty rage.

“When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” he declared in a tweet, three days after a white Minneapolis officer killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man arrested for allegedly passing a fake $20 bill, by kneeling on his neck for almost nine minutes. At one point, he applauded the National Guard for having “stopped [looters] cold” in Minnesota, as if he had just watched a football team make a particularly impressive goal-line stand; at another, he wistfully opined that the NYPD should be “allowed to do their job”—presumably, in his mind, also stopping people cold. He retweeted a conservative radio host’s ominous prediction as an implicit threat: “This isn’t going to stop until the good guys are willing to use overwhelming force against the bad guys.”

This president has long expressed a peculiar appreciation for authoritarian power and physical force. He is famously intolerant of anything over which he cannot exert control and incapable of viewing dissenters—even protesters challenging a shameful legacy of state-sanctioned racist violence—as anything other than enemies to crush underfoot. While the country tries to grapple with police brutality, perhaps more meaningfully than ever before, its chief executive is a man who openly and unapologetically endorses it.

Trump himself has little power over the day-to-day administration of law enforcement, which falls mostly to state and local authorities: governors, mayors, sheriffs. But the influence of the president’s bully pulpit is nonetheless significant, and on Monday morning, he took the nation’s governors to task, dismissing them as “weak” and urging them to “dominate” the protesters he watched on TV. “You have to do retribution,” he said, softening his apparent support for summary executions to stump for harsh mandatory minimums instead. “You have to arrest people, and you have to try people, and they have to go to jail for long periods of time.” Sentences of five to 10 years, he suggested, should be sufficient.

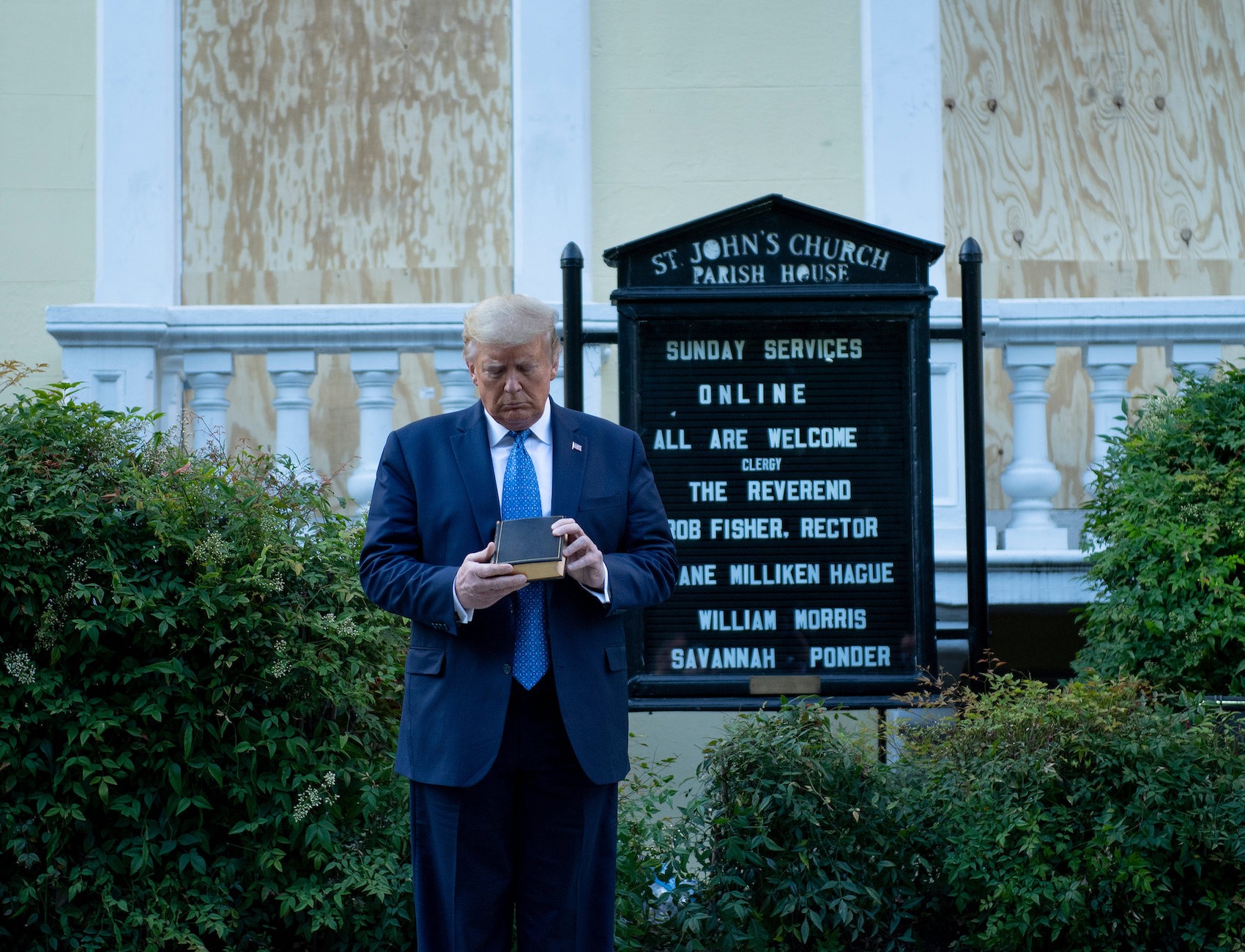

Then, in an unhinged Rose Garden address that evening, a fed-up Trump promised a crackdown, exhorting mayors and governors to “dominate the streets” with an “overwhelming law enforcement presence” in the days to come. As police on horseback fired rubber bullets and tear gas in nearby Lafayette Park, he proclaimed himself the “president of law and order” and threatened to deploy the military—an institution that he does control—to “quickly solve the problem” for cities or states that don’t do so to his satisfaction. It is hard to characterize this screed as anything other than a declaration of war on the people he ostensibly governs.

This sort of fervent cheerleading for raw power and military might is not new for Trump. In speeches, he has bemoaned the “hostility against our police,” and lashed out at laws that are “horrendously stacked against” them. He praised a Republican congressional candidate who body-slammed a reporter as “my type” of guy, and complained that the Geneva Conventions make U.S. soliders “afraid to fight,” and called for embracing torture methods that are “a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding.” While addressing a room full of law enforcement personnel in 2017, Trump encouraged them—while laughing, but not joking—to be “rough” with people they throw into the backs of squad cars.

In his Rose Garden speech on Monday, Trump called himself an “ally of all peaceful protesters,” but history shows that he is no less enthusiastic about persecuting acts of civil disobedience. He referred to Black athletes kneeling during the national anthem as “sons of bitches,” turning quiet protests of police killings into a new front in his perpetual culture wars. On the campaign trail, he offered to pay the legal fees of rallygoers who attacked protesters, and occasionally fantasized about punching them himself, pining for “the old days” when they would have been “carried out on a stretcher.”

In a 1990 interview, he expressed awe at how ruthlessly the Chinese government crushed a series of student-led pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square a year earlier. “They were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength,” he said. “That shows you the power of strength.” The exact number of victims of the Tiananmen Square massacre remains unknown, but has been estimated to be as high as 10,000.

The president’s gleeful fascination with official displays of brute force also surfaced last weekend, when he marveled at the tactical precision of Secret Service agents as they maintained the White House’s perimeter. “Whenever someone got too frisky or out of line, they would quickly come down on them, hard—didn’t know what hit them,” he mused.

If anyone had managed to breach the fence, Trump added for good measure, they “would have been greeted with the most vicious dogs, and most ominous weapons, I have ever seen. That’s when people would have been really badly hurt, at least.” To be clear, he was not insinuating that this would be an outcome he’d regret.

Three-plus years into his administration, it is beyond clear that Donald Trump has no interest in doing the work of governing traditionally associated with the position he occupies. For him, being president is simply a chance to play an important person on television, eternally in search of the respect that eluded him in his careers as a reality TV personality, golf resort developer, and failed steak magnate.

What this means, in practice, is that when faced with a genuinely difficult problem, like a real-time reckoning with centuries of unchecked police violence against people of color, Trump has no earthly idea what to do next. I am not speculating here; while cities burned on Sunday, he and his team were said to have decided he should not address the nation because he had, as the Washington Post put it, “nothing new to say,” and “no tangible policy or action to announce yet.” This is about as damning as an indictment of a leader’s competence can get.

So, when he finally decided the images on cable news were too much for a president of the United States to remain silent, Trump fell back on the one impulse with which he has always felt comfortable: unleashing the power of the state against those he sees as enemies, hoping to meet the uncertainty of the moment with the certainty of force. If protesters will not go home, arrest them. If they come back the next day, put them in prison. And if more take their place, governors willing to call in the National Guard—and maybe a president eager to see troops marching through the streets—can solve the problem in short order.

Conveniently for him, his preferred brand of lazy authoritarianism dovetails nicely with this country’s tradition of militarized policing, which defines success primarily in terms of inflicting violence, and its obsession with punishment and incarceration, which provides a ready-made infrastructure for incapacitating dissidents. Law enforcement agencies have received billions of dollars’ worth of military gear over the last several decades, flooding communities with weapons designed for combat and turning city blocks into miniature battlefields. The U.S. incarcerates some 2.3 million people in more than 7,000 jails, prisons, and other facilities, and roughly half a million of them haven’t been convicted of anything. If this country isn’t yet a police state, the tools that could be used to make it one have long been in place.

Among the many troubling implications of Donald Trump’s logic is that it contains no obvious limiting principle: Pitting police and civilians against one another like this, over and over, will eventually lead to more officers killing more people. When it happens, it won’t matter whether the victims were “looters” and “rioters” on one hand or gathered peacefully to remember the life of George Floyd on the other, because in Trump’s eyes, crime and dissent are equally wicked and equally worthy of retribution. Violence has no place in American society, unless the perpetrator is wearing a badge and riot gear, in which case the system is working exactly as it should.

Jay Willis is a senior contributor at The Appeal.