This D.A. Election Could Bring a Big Change in How Austin, Texas Treats Drug Addiction

In Travis County, thousands of people continue to be prosecuted for low-level drug possession charges that reform-minded district attorneys elsewhere have committed to dropping.

When Michael Bryant was found with illegal drugs last year, it landed him in jail for about a month, exacerbating his problems with addiction.

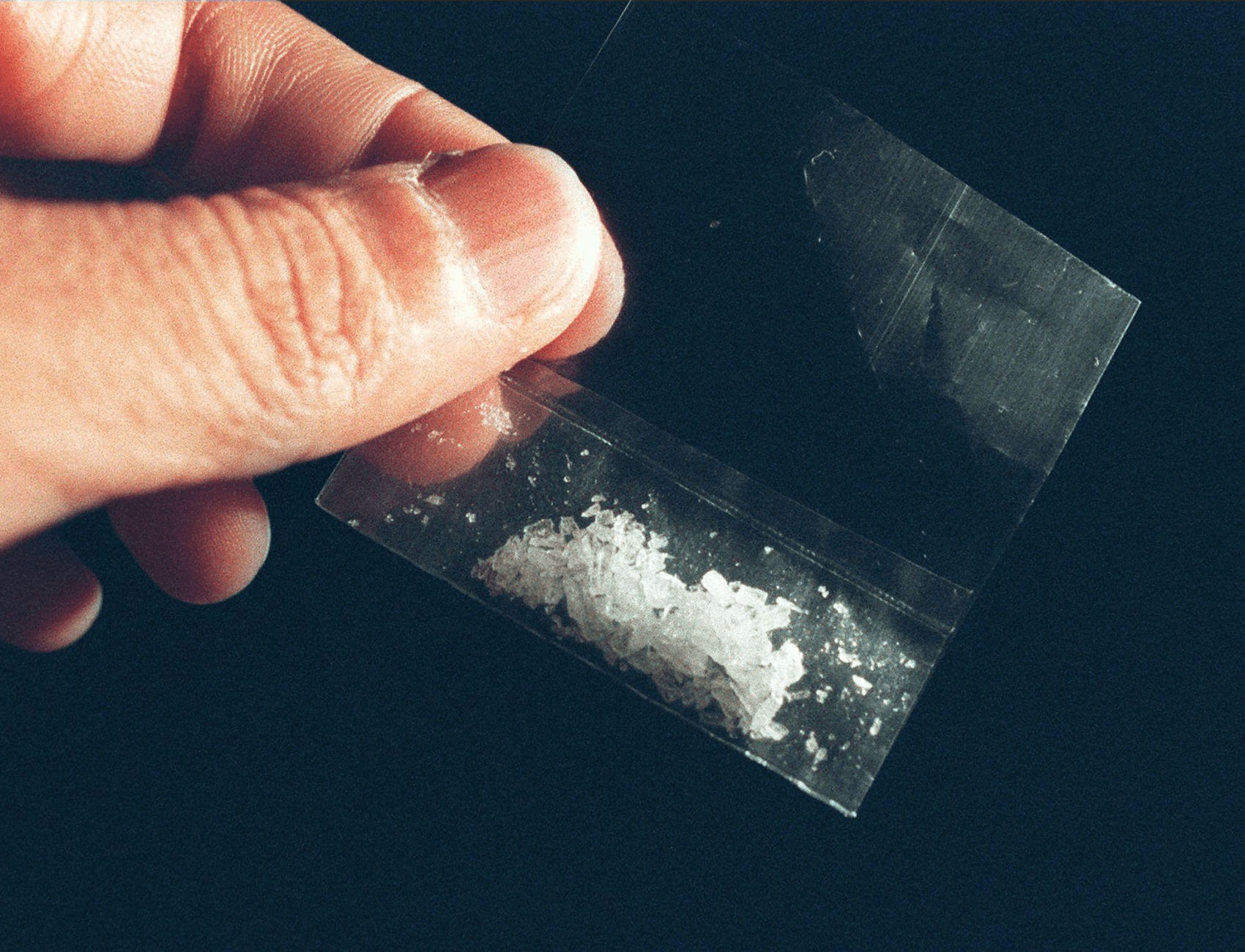

Bryant, who is now 33, had been struggling with drug addiction for much of his life, and the problems got worse in 2015, when he moved to Austin from New York after a difficult breakup. In February 2019, police found him with less than two ounces of marijuana a small amount of methamphetamines. He was charged with second-degree drug possession for the methamphetamines, even though Bryant says he had less than a gram diluted with water in a syringe.

His public defender told him that given the other drug-related felonies on his record, there was likely little he could do to avoid jail time, Bryant said. He badly needed treatment, and said he was just coming around to the idea of rehab. But before he could get help, he became entangled in the legal system and now owes thousands of dollars to probation.

“I don’t think that throwing people in jail and convicting them and throwing them in prison for small charges like that is going to do them any good,” Bryant said. “Those people aren’t going to get the help they need. They’re just going to get right out of prison and go right back to using drugs.”

Bryant was one of roughly 5,000 people arrested for drug possession each year in Travis County, a figure that reflects its punitive approach toward drug addiction, criminal justice reform advocates say. Many of those arrested are found with very small amounts of illegal drugs. The county is home to Austin and one of the most progressive in Texas, yet thousands of people continue to be prosecuted for low-level drug possession charges that reform-minded district attorneys elsewhere have committed to dropping.

Margaret Moore, who has served as lead prosecutor in Travis County since being elected in November 2016, often touts her office’s efforts to curb the prosecution of marijuana possession and to divert some people arrested for drug possession to post-arrest programs instead of charging them with state jail felonies. But she has continued to prosecute possession of less than a gram—a felony that carries a penalty of 180 days to two years in state jail and a fine of up to $10,000.

“Possession of less than a gram is one of the leading charges in Travis County,” said Cate Graziani, policy and operations director at Texas Harm Reduction Alliance. “It’s costing us a ton of money but it’s also harming the lives of so many folks in our community and I don’t think it reflects the values of our community.”

Before Moore took office, the number of arrests for possession of a controlled substance in Travis County was on the rise. Between 2013 and 2017, there was a 43 percent increase in these arrests, according to a recently released report by a coalition of four Austin-based groups. During that time, there was a 67 percent increase in the number of felony drug possession cases in the county’s courts—an increase that is more than 2.5 times higher than in all Texas courts.

Despite campaigning on a reform-focused platform, Moore did little to curb these arrests. The coalition of organizations—Texas Harm Reduction Alliance, Grassroots Leadership, Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, and the Civil Rights Clinic at the University of Texas School of Law—looked at 2,900 less-than-a-gram drug possession arrests in Travis County between June 2017 and May 2018, after Moore took control of the district attorney’s office, and found that low-level possession arrests were rampant.

“It was alarming the rate of increase,” said Douglas Smith, senior policy analyst for the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, who worked on the report.

On Tuesday, Moore will face two other Democrats, José Garza and Erin Martinson, in a competitive primary. Garza and Martinson are running on progressive platforms focused on reforming the lead prosecutor’s office. Garza said he would end the county’s prosecution of drug possession and sale under a gram and Martinson said she would examine those and other cases of low-level possession closely and would largely curb prosecutions involving small amounts of drugs.

Moore told The Appeal that her office has made great efforts in recent years to centralize drug possession charges in a single court and has diverted a growing number of people to treatment. She said she is working with local advocates as collaborators “in a quest to address their issues but still do my job.”

“They think the solution to the problem is just that the district attorney declines to prosecute all under a gram cases,” she said. “I think it’s a little more nuanced than that, so I’ve taken a different route to try to get to the same goal of the system being fair.”

But Texas-based attorneys and criminal justice reform advocates think Moore’s route isn’t enough.

“It doesn’t feel like Margaret Moore has ushered in a more progressive or even more understanding prosecution approach to drug crimes,” said Rhiannon Hamam, an Austin defense attorney who has represented people in possession cases. “People are getting picked up, arrested, booked into the jail, and then staying way too long for anybody [whose] quote-unquote crime is an illness, is a disease, is a disorder. People should be immediately connected to resources.”

In June 2018, Moore’s office launched a state jail court to consolidate all low-level drug possession cases in one place. The new court was supposed to reduce wait times and allow more people to go to pretrial diversion programs rather than face jail or prison time.

Moore said her office has moved roughly 2,700 cases from district court to this new court. Roughly 2,200 of those were for low-level drug possession, and many of them have been diverted to treatment instead of custody, she said.

“Having all those cases handled by a single prosecutor in a single court could ensure consistency,” Moore said. “I had hoped that by instituting this court … we would also be able to divert more folks or put them on community supervision so they would actually get a treatment path instead of just sitting in jail. I also wanted to reduce the time spent in jail and we wanted to reduce the amount of time it would take to dispose of these cases.”

In its first 18 months of existence, the court had a roughly 38 percent dismissal rate and a roughly 57 percent rate of convictions or deferred adjudications. Moore said that many people coming into that court have extensive criminal records, but the prosecutor won’t look at anything older than five years.

“It’s nuanced in that way,” she said. “We’re trying to focus on the current behavior of the offender, not the entire criminal history.”

But criminal justice reform advocates said that even the new court isn’t enough. Instead of arresting people with addiction issues, advocates said Moore’s office should be focused on pre-arrest diversion programs, which would help people avoid criminal records and costly, burdensome interactions with the court system. Currently, many of the people who eventually plead guilty and agree to pretrial diversion have already spent time in jail.

In their recent report, the Austin-based organizations noted that half of the possession cases relating directly to medical or mental health crises resulted in jail time between two days and two years.

That period of confinement, even brief, can be damaging for an individual with substance abuse issues, Smith said.

“Arresting someone in and of itself is problematic, particularly if they have other things going on in their life like substance use or if they’re caring for children or if they have a job,” he said. “Every day incarcerated brings mounting consequences for an individual.”

Bryant said he suffered while in custody. “You get really lonely,” he said. “You’re stuck in a place where you can’t go and use. You can’t medicate yourself like you normally do, so your anxiety gets driven up, your depression gets driven up, you start to get mentally fucked up in the head.”

But he was determined to go to rehab, and said he was lucky that a judge understood his desire for treatment. After about a month in jail, he was released with an ankle monitor and given 48 hours to check into a facility.

Bryant says he got clean in rehab and is grateful for the opportunity. But because of his criminal record and various charges stemming from his addiction, he has since struggled to find an apartment and secure a job. He was turned down from positions at a call center and as an Amazon delivery driver.

“It makes it super hard to stay clean because you’re trying to build yourself back up, not only emotionally and physically but financially,” he told The Appeal. “When you’re not able to get a job, it’s not only a rejection but it kind of tears you down and it kind of makes you feel like you’re going backwards.”

Moore told The Appeal that her office is working on setting up a pre-arrest diversion program. Advocates are meeting with the police department and Moore’s office to discuss what that program could look like, and if it should be modeled on Seattle’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program.

“That is a conversation that is developing. I think it’s getting much closer to bearing fruit,” she said. “In the meantime, we’re dismissing a bunch of cases and we’re diverting others.”

Both candidates challenging Moore have been critical of her drug prosecutions. Garza told The Appeal that as district attorney, he would stop prosecuting possession and sale of a controlled substance of less than a gram.

“Right here in the most progressive county in the state, every single year the district attorney’s office brings more drug possession cases than any other kind of offense,” he said. “I’ve been very clear that when we win, we’re going to end the prosecution of low-level drug offenses in Travis County.”

Martinson did not directly commit to ending the prosecution of possession and sale of less than a gram, but said she would look at each case individually, including those accused of possession over a gram, to determine if prosecution is necessary.

“Recognizing that addiction is a lifelong process and that the criminal justice system is not effective at forcing people to become sober, what I’m focused on is getting people with substance use disorder connected with resources,” she told The Appeal.

Both candidates criticized Moore’s reliance on post-arrest diversion, explaining that a successful intervention would come pre-arrest so that individuals don’t end up with criminal records, or tied up in a legal system that will penalize them if they violate a program because of continued addiction issues.

Garza also pointed to the racial disparities in prosecutions and data showing that holding people with substance use issues in custody increases the likelihood that they will reoffend. “The data is very clear that prosecuting these types of offenses makes us less safe,” he said.

According to the analysis of county arrest data by the coalition of local organizations, drug possession arrests disproportionately affect women and people of color. In 2017, possession was the fourth-leading charge contributing to days spent in the county jail for women. The following year, county officials were expected to approve a $79 million bond to build a new jail for women to accommodate the growing number of arrests for drug possession.

From 2017 to 2018, 29 percent of cases for possession of less than a gram were Black people, even though the county is less than 9 percent Black.

“These kind of offenses are one of the greatest drivers of racial disparities in our criminal justice system,” Garza said. “It’s time for bold reforms to begin to strike at these racial disparities and to keep our community safe.”

If the next district attorney in Austin were to eliminate these prosecutions, the city would be following the lead of King County, Washington, home to Seattle, which in late 2018 became the first in the nation to stop charging people for possessing amounts of drugs less than a gram. The move was part of an effort to treat addiction as a public health crisis and not a crime.

Seth Manetta-Dillon, a defense attorney in Austin, explained how Travis County needs to follow suit and should tackle the underlying poverty, housing, and mental health issues instead of relying on arrests and confinement.

“You have to attack it from all the different angles and provide services and the probation department here certainly can’t do that,” he said. “I think the district attorney’s office has to be aware of that and stop convicting people for it if they’re not going to provide actual services, because then it’s just a recurring cycle over and over and over.”

Chris Harris, an Austin organizer and criminal justice reform advocate, said it’s the district attorney’s job to shift the conversation from prosecutions to treatment.

“We need to have a district attorney who has that mindset to fight for resources outside the courtroom and helps prevent things from becoming criminal justice issues,” he said.

Graziani of the Texas Harm Reduction Alliance agreed that the next district attorney should prioritize diverting resources to harm reduction and substance use disorder services.

“This would be a huge shift and it’s troublesome and worrisome that Margaret Moore has not committed to making that shift,” she said.