This Red State Governor Is Giving Hope To People Sentenced To Die In Prison

But after a spree of commutations, the governor recently put down his clemency pen amid tough-on-crime fear mongering.

In 2016, after serving nearly 27 years in prison, 61-year-old Kerry Myers experienced something he didn’t know would ever happen: Christmas at home with his family.

At the time of his sentencing for second-degree murder in 1990, Louisiana was enforcing decades-old “life means life” laws that meant that unless Myers could prove his innocence, he would die in prison. Louisiana is one of two states that mandates life without parole for second-degree murder, and almost 5,000 people are currently serving sentences with no chance of parole or probation.

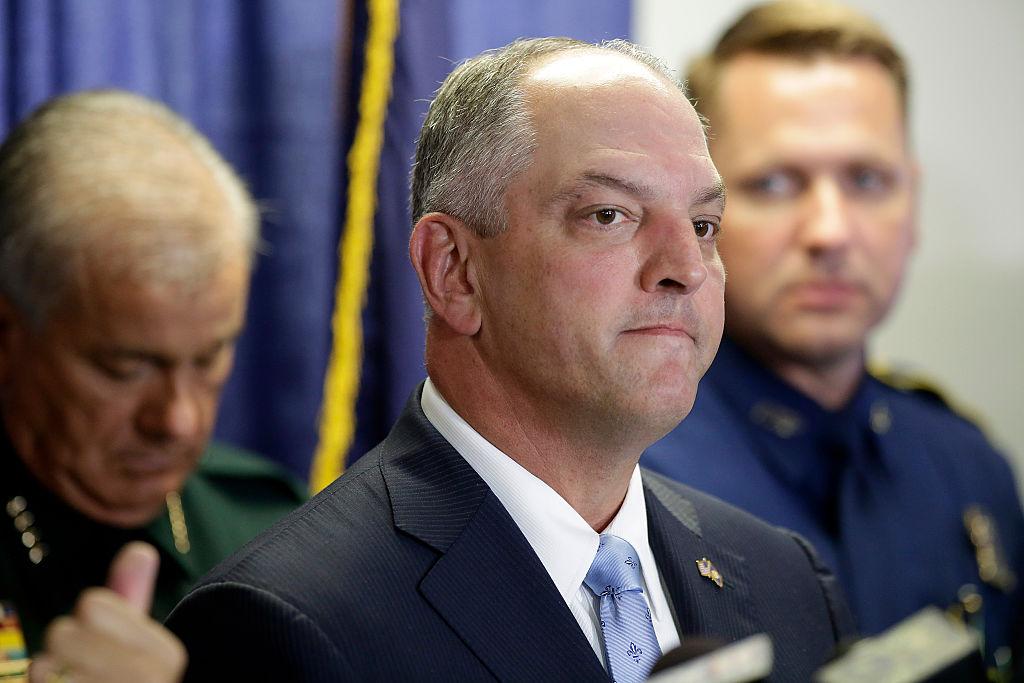

But Myers wasn’t ready to accept his life sentence. He kept fighting to prove his innocence and applied for clemency from the governor. For a long time, the chances of either proving successful were low. Then Governor John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, took office in 2016.

After campaigning in the deep red state on a promise to reduce its prison population, Edwards set his sights on changing Louisiana’s reputation as the incarceration capital of the nation. One of his first actions was to give relief to people like Myers serving long sentences for violent crimes. In his first six months in office, Edwards commuted 22 sentences out of 56 sent to him with positive recommendation from the state’s Board of Pardons. Sixteen of the offenders whose applications he granted were serving life without parole.

Just a few days days before Christmas, the warden told Myers that Edwards had signed his application and had granted him immediate release. Four days later, he was home near Baton Rouge, celebrating Christmas with his mother, brother, daughter, grandchildren, and extended family.

“It was amazing,” he said. “It was a fantastic reunion.”

Edwards’s commutation spree stood in stark contrast to how his predecessors used their power. Neither Governor Mike Foster, a Republican, nor Kathleen Blanco, a Democrat, signed any commutations in their first year. (Foster waited almost three years to start signing pardons and commutations, but focused on nonviolent offenders.) Blanco commuted 129 sentences in four years, and Foster commuted 52 in eight years, but the majority came during their last few years in office.

Governor Bobby Jindal, who served most recently, approved one clemency application in his first year but only three during his eight years in office. While the Pardon Board sent many applications with positive recommendations to his desk, Jindal, a Republican, ignored the vast majority. That included Myers’s, which the Pardon Board recommended in 2013.

How often Democratic governors grant commutations appears to have more to do with the governor than the political makeup of their state. In solidly Democratic New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo granted only seven commutations in December 2016 and just two since then. But in California, Governor Jerry Brown, a Democrat, commuted 49 sentences in the final two years of most recent his term.

Criminal justice reform advocates credit Edwards for bringing long-needed change to Louisiana’s justice system—not just through his clemency push but also by spearheading a legislation package that lowered mandatory minimum sentences, expanded alternatives to prison, and made it easier for nonviolent offenders to get out of prison early. Thousands of people have since been released, and last year Louisiana lost its title as the state with the highest incarceration rate in the nation. Edwards’s renewed use of the clemency power made many of the lifers at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, hopeful for the first time in decades.

“I can tell you most certainly there was renewed hope,” said Andrew Hundley, the executive director of the Louisiana Parole Project. “For so long, there wasn’t hope. … There’s about 6,000 people at Angola and about 5,000 of them have life sentences or sentences akin to life sentences, so the majority of people who go to Angola won’t leave Angola.”

Hundley was himself sentenced to life without parole as a juvenile, but was also released from Angola in 2016 thanks to Edwards’s bill that prohibited that sentence for young people. He said that Edwards’s use of his clemency power had positive effects across Angola. Many offenders who previously assumed they would die inside prison suddenly started trying to improve their behavior, as a favorable recommendation from the pardon board requires an applicant to be free from disciplinary reports for 24 months. Inmates also began applying for educational opportunities and prison organizations to boost their applications. “Edwards may not realize this but he’s the warden’s best friend,” Hundley said.

But then the commutations stopped.

In the last year and a half, since the end of 2016, Edwards has not signed a single commutation. The pardon board has issued at least 70 positive recommendations to people seeking commutations since December 2016, when Edwards signed his last commutation, according to an analysis by The Appeal. Representatives with his office did not respond to questions about why the commutations stopped.

Advocates like Norris Henderson, who leads the civil rights nonprofit Voice of the Experienced, say they understand why Edwards has put down his clemency pen. The governor is up for re-election next year, and they say it would be dangerous for him to do anything that could jeopardize his chances of serving another term.

“I think he’s just being cautious,” Henderson said, pointing out that as the lone elected Democrat in Louisiana, Edwards has a long list of opponents who would capitalize on any misstep. “Some of these folks are trying to use any excuse possible to throw a brick at you.”

“He’s doing his due diligence,” Myers agreed. “The political fallout could wreck someone who has an opportunity to do good. … You have to be there to do good.”

While his efforts have garnered praise outside the state, Henderson said it’s common knowledge in Louisiana that supporting criminal justice reform can be a politically dangerous position. Edwards is already facing pushback from the state’s district attorneys, who have said they need more time to consider each application. (E. Pete Adams, the executive director of the Louisiana District Attorneys Association, said the DAs respect the governor’s commutation authority, as long as victims and their representatives are given notice and the opportunity to be heard.)

Two Republicans, U.S. Senator John Kennedy and state Attorney General Jeff Landry—both considered potential opponents for Edwards in next year’s election—have already gone after the governor for being too lenient on crime, with Kennedy calling Edwards’s package of reforms an “unqualified disaster.”

If just one of individuals whose sentence Edwards commuted or who have been released were to violate their parole or get sent back to prison, Edwards’s ability to use his clemency power could be over.

“People are looking for a Willie Horton,” Henderson said, referring to the man who was convicted of a rape and other crimes committed while on a Massachusetts weekend furlough program and may have cost the state’s governor at the time, Michael Dukakis, the 1988 presidential election.

The pause in commutations is also easier for advocates and offenders in Louisiana prisons to understand because of the widespread belief that it’s just that—a pause and not an end. “I don’t think he’s going to shut down the process,” Henderson said. “I trust that once things start shaking themselves off around the budget and the governor’s office gets a handle of where we are fiscally, then I think we’ll go back to things as normal.”

Many believe they will have to wait to see if Edwards wins a second term in 2019. In the scheme of things, Henderson said another few years is nothing compared to the decades many have been waiting. “Folks will understand,” he said.

They also understand that if he wins re-election—which polls last winter showed would be difficult but possible—Edwards would not have to worry about the potential pushback that granting mass clemencies would bring. “The prison population wants to see him become a second-term governor because of pardons and the assumption that he would do more criminal justice reform in his second term,” Hundley, of the Louisiana Parole Project, said. “There’s an understanding—don’t expect any more pardons before the election.”

But advocates are also thinking about how to keep the commutations coming if Edwards were to lose. Voice of the Experienced is advocating a bill that would relieve a governor of some responsibility by making it possible for a recommendation that sits on the governor’s desk for 90 days to be considered signed. That change would also relieve some of the stress on the prisoners, Henderson said. “It’s very disheartening for a person who gets a recommendation and then is sitting there five years, six years, seven years,” he added.

Myers, who said he feels lucky to have had his application considered in Edwards’s first group in 2016, said he will do his part to make him a second-term governor who can continue signing clemency applications.

“I talked to him and I said, ‘You know I do get to vote in the next election now,’” Myers said, remembering when he got to meet and thank Edwards last year. “I said, ‘You can probably count on my vote.’”