The Secret Story of Corruption Behind Meek Mill’s Incarceration

On Jan. 23, 2007, a pair of officers from the Philadelphia Police Department’s Narcotics Field Unit (NFU) received information from a “reliable source” that drug sales were being conducted in the vicinity of 22nd and Jackson Streets, on the city’s south side. “Numerous B/Ms” — NFU officers Reginald Graham and Sylvia Jones would later write in a […]

On Jan. 23, 2007, a pair of officers from the Philadelphia Police Department’s Narcotics Field Unit (NFU) received information from a “reliable source” that drug sales were being conducted in the vicinity of 22nd and Jackson Streets, on the city’s south side. “Numerous B/Ms” — NFU officers Reginald Graham and Sylvia Jones would later write in a Philadelphia Police Department Investigation Report, in cop shorthand for black males — were selling drugs while on bikes and on foot in the area. The supplier for the corner dealers, the police’s confidential informant said, was based at 2204 South Hemberger Street, a brick rowhouse in the same South Philly neighborhood.

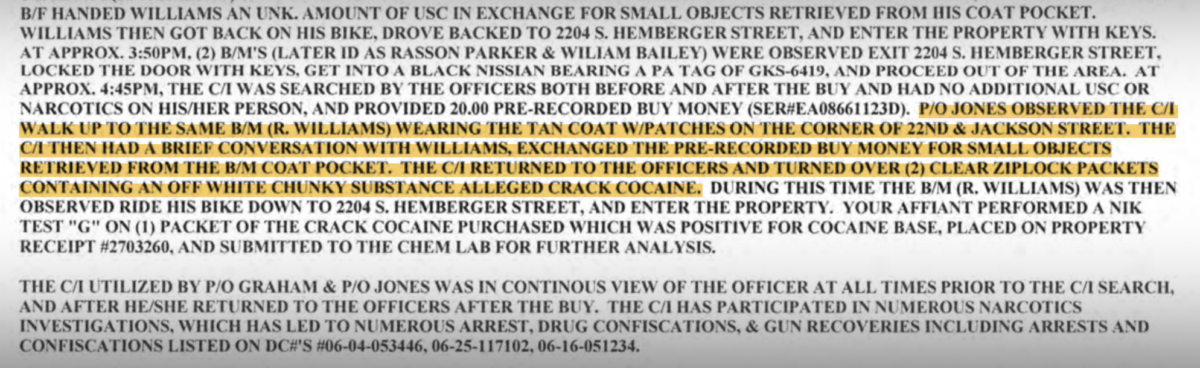

The officers then met up with the informant to begin an investigation into suspected drug activity at 2204 South Hemberger. It was a chilly day in Philadelphia, with the temperature hovering around 30 degrees and a light dusting of snow, about a tenth of an inch, covered the streets. At approximately 3:30 that afternoon, Graham and Jones said they observed a 5 feet 8 inches tall black man with a medium complexion wearing a tan coat with patches on its sleeves — who they later claim to have identified as 19-year-old Robert Rihmeek Williams (aka Meek Mill), even though he is 6 feet 2 inches and dark-complexioned — exit the home and then ride his bike to 22nd and Jackson streets. At the intersection, the officers said, they watched as a black female handed Williams “an unk. [unknown] amount of USC [United States Currency]” in exchange for “small objects retrieved from his [Williams’] coat pocket.” Graham and Jones then gave their informant 20 bucks in “buy money” to approach Williams for drugs; moments later, at the same street corner, the informant allegedly obtained what the officers again described as “small objects” from Williams once the buy money exchanged hands. Back at 2204 South Hemberger, Graham and Jones performed a “NIK” test (a narcotics field test) of the substance allegedly sold by Williams which they said tested positive for crack cocaine. It’s unclear if a laboratory test of the drugs was ever conducted — Williams’s current attorneys say that such a test is “noticeably absent” from his trial record — which is troubling given the unreliability of narcotics field tests.

It is not apparent from from either Graham and Jones’s initial arrest report or an investigation report, completed months later, exactly when the officers identified the 5 feet 8 inch black male engaged in a drug deal as Williams. Meek’s attorneys told The Appeal that on January 23 he was not in the vicinity of 2204 South Hemberger but was instead in court with a cousin. Despite the shaky identification of Williams, on January 24, Graham and Jones set up surveillance in the vicinity of 2204 South Hemberger. When Williams exited the home he allegedly “looked at the officers … and began to tug on a dark object in the front of his pants.” Graham and Jones, who were clad in tactical “raid gear,” yelled “police!” and then, they said, Williams pulled a gun from his pants and aimed it directly at them. A foot pursuit ensued and the officers tackled Williams to the ground between two parked vehicles. According to Graham and Jones, they retrieved a loaded SIG Sauer 9mm and a Ziploc bag containing marijuana from Williams. Several police officers then conducted a search of 2204 South Hemberger and reported that they found drugs and about $6,800 in cash.

Williams was handcuffed, arrested, booked on drugs and weapons-related charges, and then hospitalized as a result of injuries he sustained that day, which he claimed came from a severe beating by the police. In a mugshot, Williams’s left eye is swollen shut and there is a large bandage over his right eye. Williams has also said that the police ripped braids from his head, a claim corroborated in a sworn affidavit recently provided to Williams’s attorneys by a former Philly cop. “Every last cop hit me when I got in,” Williams said. “I maybe got knocked out two or three times from getting kicked in my face.” About five months after the arrest, during the summer of 2007, Williams was released on bail.

But Williams wasn’t truly free. The January 2007 arrest by a particularly aggressive unit of the Philadelphia Police Department began his now more than decade-long journey through the city’s criminal justice system. His case has been plagued by a staggering number of allegations of judicial, police, and prosecutorial misconduct; some misconduct dating back to 2007 has only recently been revealed. The case’s unusual complexity is matched by the high-profile nature of the defendant. Then-teenaged Robert Rihmeek Williams, who had been battle rapping on Philadelphia’s streets since he was 14, has since become hip-hop sensation Meek Mill, famous thanks to albums like Dreams Worth More than Money (which debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 upon its 2015 release), constant tabloid interest in his relationship with fellow superstar Nicki Minaj, and backing from Jay-Z’s management company Roc Nation.

The teen with long braids and a baby face who was arrested by NFU cops on a freezing, snowy Philadelphia street in 2007 barely resembles the Meek of today: He is now a 30-year-old father of a 7-year-old son, and has not been convicted of another crime since a judge handed down a guilty verdict in 2008 related to his drugs and weapons arrest the prior year. Nonetheless, like millions of black men in America, he has effectively been trapped in the criminal justice system ever since. Since Nov. 6, 2017, Meek has been incarcerated at the State Correctional Institution in Chester, Pennsylvania for violating probation. Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas Judge Genece Brinkley handed him a two- to four-year prison sentence after he failed a drug test and allegedly did not comply with a court order limiting his travel. It was the third time since 2011 that Brinkley revoked Meek’s probation, each time due to similar allegations.

Indeed, Meek’s case illustrates the vast and perhaps under-recognized role that probation plays in America’s unmatched carceral state. The number of people on probation rose from 1.1 million in 1980 to nearly 3.8 million in 2015, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). People of color are vastly over-represented in the parole and probation population, per the same BJS study. In 2015, one-third of the 4.65 million Americans who were on some form of probation or parole were African American. Because probation comes with innumerable conditions — from drug tests to meetings with a probation officer to restrictions that require approval from a judge for out-of-state travel — violations are commonplace, creating a punitive cycle of violations followed by even more punishment. “The probation system has never been about helping people move on with their lives after committing a crime,” wrote journalist Michael Thomsen in a 2015 essay for Al-Jazeera America proposing the elimination of criminal probation. “Instead, it has enabled the government to dig deeper into peoples’ private lives in search of punishable flaws.”

This morning, there was a status conference in front of Judge Brinkley regarding a petition by Meek’s attorneys filed under Philadelphia’s Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA). In the petition, they present two sworn affidavits from former Philadelphia police officers who have been accused of corruption themselves. One officer, present at the arrest, claims that Graham lied at trial, providing strong corroboration for Meek’s entire theory of the defense. The officer claims that Meek never ran, never struggled with the officers during his arrest, and, critically, that Graham belatedly came up with the story about Meek pointing a gun at the officers.

More damningly, the officers allege that Graham, who provided the critical testimony at Meek’s trial, regularly lied and cheated by making up probable cause justifying searches, stealing money during searches and arrests, and beating up suspects, as Meek testified happened when Graham arrested him. And finally, Meek’s attorneys have pointed to a newly released “do-not-call” list from the Philadelphia district attorney, which identifies police officers who prosecutors deemed unworthy of belief, including Graham.

At trial, the government’s case hinged entirely on the credibility of Graham, the sole witness, and Meek’s lawyers believe their new evidence obliterates it. They have asked Brinkley to vacate Meek’s convictions and release him on bond pending resolution of this matter.

At this morning’s status conference, the Philadelphia DA’s office said that because of questions surrounding Graham’s credibility, Meek’s conviction on drug and weapons charges should be vacated and he should be granted a new trial. The DA’s office also reiterated its support for Meek’s release on bail.

It is unclear when — and how — Brinkley will rule on Meek’s PCRA. But this morning, Brinkley refused to even hear arguments that Meek should be released on bail and simply scheduled another hearing for June. So if court today and history are any guide, she’s likely to hand down an adverse decision in the rapper’s case. In her past interactions with Meek, she has harshly punished him for minor violations, sometimes ignoring the advice of prosecutors and Meek’s probation officer; additionally, his attorneys have accused her of everything from inappropriate ex parte communications with Meek to retaliating against a former police detective who performed renovation work that dissatisfied her on her Philadelphia home. (Brinkley did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Appeal regarding Meek’s case or the allegations of impropriety against her.)

Unsurprisingly, on March 29, Brinkley denied Meek’s motion for bail pending his as-yet-to-be scheduled PCRA hearing. “This court has impartially and without prejudice presided over numerous proceedings in this matter since 2008,” Brinkley wrote, “long before his current counsel became involved one week before the violation of probation hearing. None of the allegations by [the] defendant constitute evidence that this court is unable to act impartially and without personal bias or prejudice with respect to this matter.”

When Meek went to trial in the summer of 2008 on drugs- and weapons-related charges, well-known mob defense attorney Joseph Santaguida represented him. Santaguida’s other clients included “Skinny Joe” Merlino, known as the Philadelphia Mob boss, and many other members of the area’s organized crime scene. A former assistant U.S. Attorney with the Organized Crime Task Force described him as “right out of Central Casting for what you’d expect as the lawyer for mobsters.” Despite his extensive criminal defense experience, Santaguida made a questionable choice at trial: With Meek’s consent, he waived Meek’s right to a trial before a jury.

The jury system is a centerpiece of the American criminal justice system. The right to be judged by 12 peers ensures that 12 people, not one, all must agree that a defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If one person has doubt, the government is denied its conviction. Waive that right and present the case to a judge, and the accused’s fate comes down to one person. It is an extraordinary gamble.

In this case, Santaguida’s risky move placed Meek’s fate in the hands of Judge Brinkley, who is well-known for courting controversy in and out of the courtroom. She once jailed a court reporter with mental illness for not completing transcripts, she sued a hotel for $12,000 because she suffered “trauma” and sleeplessness after the hotel employee left a name tag in the hotel bed, and she has allegedly used her role as a judge to threaten multiple tenants for failing to pay rent. She also became the sole decider of Meek’s future.

The case hinged on whether Brinkley should believe the government’s only witness, Officer Graham — who portrayed Meek as a menace to law enforcement and claimed Meek “pointed [a] gun in [the officers’] direction” — or Meek, who testified that when police approached him, he tossed his gun but never pointed it at an officer, and that he never tried to flee and never struggled with the police. The judge chose to trust Graham and on Aug. 19, 2008, found Meek guilty of possession with intent to deliver narcotics, possession of narcotics, simple assault, carrying a firearm without a license, carrying firearms in public, possession of an instrument of a crime, and carrying a loaded weapon. On Jan. 16, 2009, she sentenced Meek to 11–23 months in prison with eight years probation. No lawyer filed an appeal, although Meek had a constitutional right to one. He remained in prison until July 2009, when he was released on parole. Six months later, he started probation, under Brinkley’s careful watch.

Since his trial, Meek and Brinkley have engaged in a long and troubling dance. The judge has exercised enormous control over the details of Meek’s life: She has decided, for example, whether and when Meek can travel to his concerts and when he can perform for pay — a highly unusual and intrusive role for a judge to play. She has repeatedly extended his probation and sentenced him to more jail time and house arrest — and now prison time — for small violations. In 2011, Meek tested positive for opiates, and Brinkley found him in violation of his probation. In 2012 police arrested him, claiming they smelled weed in his car (he was arrested for refusing a search). No criminal charges followed, but Brinkley again found him in violation. She ordered two drug tests, both of which were clean, and also banned him from significant work travel, but she did not revoke his probation or send him to prison.

It was not necessarily Meek’s technical violations, however, that have set Brinkley off the most. Brinkley’s interest in Meek’s life appears to extend well beyond that which is appropriate for a judicial officer, and she has reserved particular umbrage for Meek’s split from Charlie Mack, his manager, and Meek’s decision to sign with Jay-Z’s Roc Nation. She has repeatedly encouraged Meek to return to his old manager.

Mack is the former manager of the R&B group Boyz II Men. Sometime around 2009, Mack claimed he could help Meek with his legal problems and encouraged Meek to sign him. Meek did, and he was released from house arrest not long after. But in 2011, Meek alleged that Mack stole money from him and fired him, signing with Roc Nation. (Mack has his own criminal history.)

Although she later claimed otherwise, this move appeared to incense Brinkley, the probation officer Brinkley had hand-selected in 2012 to oversee Meek’s case, and Assistant District Attorney Noel DeSantis, then-assigned to Meek’s case. In the 2012 hearing, Brinkley complained that Meek had changed managers, blaming any problems Meek had on his new contract with Roc Nation: “He didn’t have no problems with the other manager, so you all let him down this time,” she said, addressing his new manager. In 2013, she complained: “It was when the defendant got new management that apparently there became some miscommunication about travel and I said that before and I’m saying it again.” She again lamented the absence of Mack in Meek’s life in 2014, and in a 2016 hearing both the probation officer — who communicated with Mack nearly 40 times in 2016 — and the ADA did the same. The probation officer also referred to Mack as “phenomenal.”

Of the judge’s relationship with Mack, Meek’s attorney Jordan Siev told The Appeal: “Meek was introduced to Mack by someone, we don’t know who, who told him Mack was someone who knew how to get the judge right on probation. He was told if he hired Mack he would get out sooner.” As the years passed, Meek stayed out of trouble, but Brinkley nonetheless seemed to grow increasingly frustrated with him. In 2012, she denied him permission to travel. In 2013, she ordered him to take etiquette classes from an acquaintance of Mack’s and again denied him the right to travel. And then, in 2014, Brinkley sent Meek back to jail for three to six months, angry that he did not get her permission to travel and that he tested positive for the drug Percocet. But that wasn’t the worst part of his punishment; Brinkley extended his probation for another five years. Siev calls Brinkley’s interest in Meek’s probation “highly unusual, I have talked to defense attorneys everywhere and they said they have never heard of a situation like this.”

As Meek struggled in Brinkley’s courtroom, the credibility of the cop who arrested him in 2007 and testified against him a year later began to unravel. In November 2013, Officer Reginald Graham approached the FBI, unsolicited, regarding what was then a fast-intensifying federal investigation into allegations that the Narcotics Field Unit was stealing large amounts of drugs and cash from Philadelphia residents. During his FBI interview, Graham confessed that he received cash recovered during NFU searches — but he nonetheless failed a polygraph examination administered by the bureau regarding his conduct as a police officer. The Philadelphia Police Department’s Internal Affairs initiated an investigation of Graham, and sustained accusations against him including engaging in criminal conduct, theft, and lying during an investigation (Graham retired from the Philadelphia Police Department in 2017).

Nearly one year later, in October 2014, six NFU officers were indicted in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania on an array of charges including robbery, extortion, falsification of records, and racketeering conspiracy. Federal prosecutors alleged that the NFU was effectively a criminal enterprise that stole drugs and cash from the homes and vehicles of Philadelphia residents. In a single day — Oct. 16, 2007 — NFU cops Brian Reynolds, Jeffrey Walker, and Thomas Liciardello allegedly stole $30,000 in drug proceeds seized from a car belonging to a man identified in court documents only as “RK” and $80,000 from a safe in RK’s apartment. Federal prosecutors alleged that when the trio of cops documented the seizures they reported that only $13,000 was seized from RK and didn’t mention the $80,000 from his safe.

But when the NFU officers headed to federal court in the early spring of 2015, they were acquitted of the 47 charges containing 26 separate criminal counts in the indictment. The nearly 52 day trial likely ended in acquittals because it was built on the testimony of unsavory witnesses: suspects in drug cases and NFU cop-turned-witness Jeffrey Walker, who pleaded guilty in a separate corruption case in 2014. Despite the not-guilty verdicts — and the NFU officers returning to their jobs with the Philadelphia Police Department — some measure of justice was served to the Philadelphia citizens they had arrested in the past. In the years following the NFU indictment, over 800 criminal convictions related to the unit have been vacated by Philadelphia courts.

NFU misconduct reverberated far beyond the collapsed federal case against them. Officer Walker, a key government witness at the 2015 NFU trial, later testified in civil depositions about misconduct committed by Officer Graham, including alleged acts of perjury. Then-District Attorney Seth Williams — who is now serving a five-year federal prison term in an unrelated bribery case — created a secret “do not call” list of current and former Philadelphia police officers who were not to be used by prosecutors because the DA could not vouch for their credibility. Graham was included in the “do not call” list, a fact not disclosed to Meek’s attorneys. Disclosure is arguably required by law under Giglio v. United States which held that a defendant’s due process rights are violated when the government does not disclose impeachment information regarding its witnesses. Indeed, Meek’s current attorneys contend that no Giglio material concerning Officer Graham was handed over by the Philadelphia DA’s office to his trial or post-conviction counsel. That claim was backed up by the current Philadelphia DA who asserted in a recent filing that, “at some point prior to 2018, the Commonwealth became aware of some issues or conduct bearing on the credibility of Officer Graham, yet there is no indication this material was timely given to the Court or Petitioner.”

Meek was released from jail in December 2014, and for about a year, he seemed to stay in Brinkley’s good graces. But in December 2015, he found himself again at the judge’s mercy. The allegations? That he failed to notify his probation officer of a change in location for a music video shoot, arrived three hours late for a probation appointment, hung up on the officer as she reprimanded Meek, and submitted water instead of urine during a drug test — Meek’s attorneys disputed this latter allegation, claiming that the lab technician threw the sample away before actually testing it. Brinkley, the probation officer, and the DA complained primarily that Meek traveled for work without permission and Brinkley immediately barred Meek from any paid performances and, strangely, from going to visit his mother in New Jersey.

Meek’s precarious position did not stop the courtroom clerk, Wanda Chavarria, from trying to elicit his aid. At the December 2015 hearing, Chavarria slipped him a note, begging for assistance in paying her son’s college tuition. “IT TAKES A VILLAGE!” she wrote. Meek declined, afraid of any appearance of impropriety. (Chavarria was later fired).

The scene grew more bizarre in February 2016, when Meek’s then-girlfriend Nicki Minaj, one of the world’s biggest hip-hop stars, entered the courtroom to testify on Meek’s behalf and observe. Seemingly star-struck, Brinkley repeatedly asked Minaj questions from the bench, and then asked Meek and Minaj to join her in chambers — without Meek’s attorney — at the end of the hearing. Such ex parte proceedings raise red flags. They are not on the record and therefore what transpired is not subject to review by a higher court. In this case, the conversation occurred without Meek’s then-attorney present as a witness able to protect Meek’s rights. According to Meek’s current defense team, during that meeting, Brinkley purportedly gave Meek career advice, suggesting that he record “On Bended Knee,” a hit song by former manager Charlie Mack’s clients Boyz II Men, and dedicate it to her. (In that same sentencing hearing, the probation officer and DA again complained about Mack’s absence.)

Meek declined to record the song and Brinkley sentenced Meek to 6–12 months in jail with immediate release to house arrest and daily community service for 90 days. And again, she extended his probation, this time for six years — it would be 2023 before he would stop reporting to her. If Meek wanted to appeal or file a motion to reconsider, he should have second thoughts: “[I] can give out a greater sentence,” she threatened, “the sentence could go up, not down.”

In November 2017, Brinkley hauled in Meek for yet another probation violation hearing, even though no party to the case, including the new probation officer nor the assistant district attorney assigned to the case, requested one. (Brinkley nonetheless ordered the parties to include the former ADA on all notice and communication, despite her lack of legal involvement — a decision that one of Meek’s attorneys describes as highly improper and unusual given that she is no longer at the office.)

Meek allegedly failed a drug test because of an addiction to opiates — he was receiving treatment — and law enforcement in St. Louis gave Meek a citation for defending a friend at an airport after a fan sucker punched the friend, angry that Meek refused to take a selfie with him. Police subsequently dropped the charges after finding Meek’s actions justified. And incredibly, police in New York arrested Meek for popping a wheelie on a city street in front of a group of fans. New York City police did not observe the offending bike trick firsthand — they viewed it via a video posted on Instagram. “Williams was arrested the next day while he was in a car,” Meek’s attorneys said, “not on a bike.” The prosecutor did not ask Brinkley to find a probation violation and did not ask for a prison sentence, and the probation officer recommended that the judge decline to find a probation violation and keep Meek out of prison.

Normally, the government and probation officer’s request for no punishment would end the matter, but not with Brinkley. She complained that Meek sought treatment for his opiate addiction in Atlanta instead of California, a change of which she had already been notified by both Meek’s management and the probation officer; that he dared to ask for permission to conduct work travel (but not that he traveled without permission); and that he failed to travel for one work trip to Greece that she had pre-approved. She also expressed dismay that during his community service at the Broad Street Ministry in Philadelphia, Meek sorted clothes — the task he claims was assigned to him — instead of feeding the homeless, which she observed during a surprise visit to the site she decided to make herself, a task normally reserved for the probation officer. Based on this conduct, she sent Meek back to prison, sentencing him to two to four years of incarceration with probation terminated. “You won’t have to report to me ever, and I don’t have to deal with you ever again,” she told Meek.

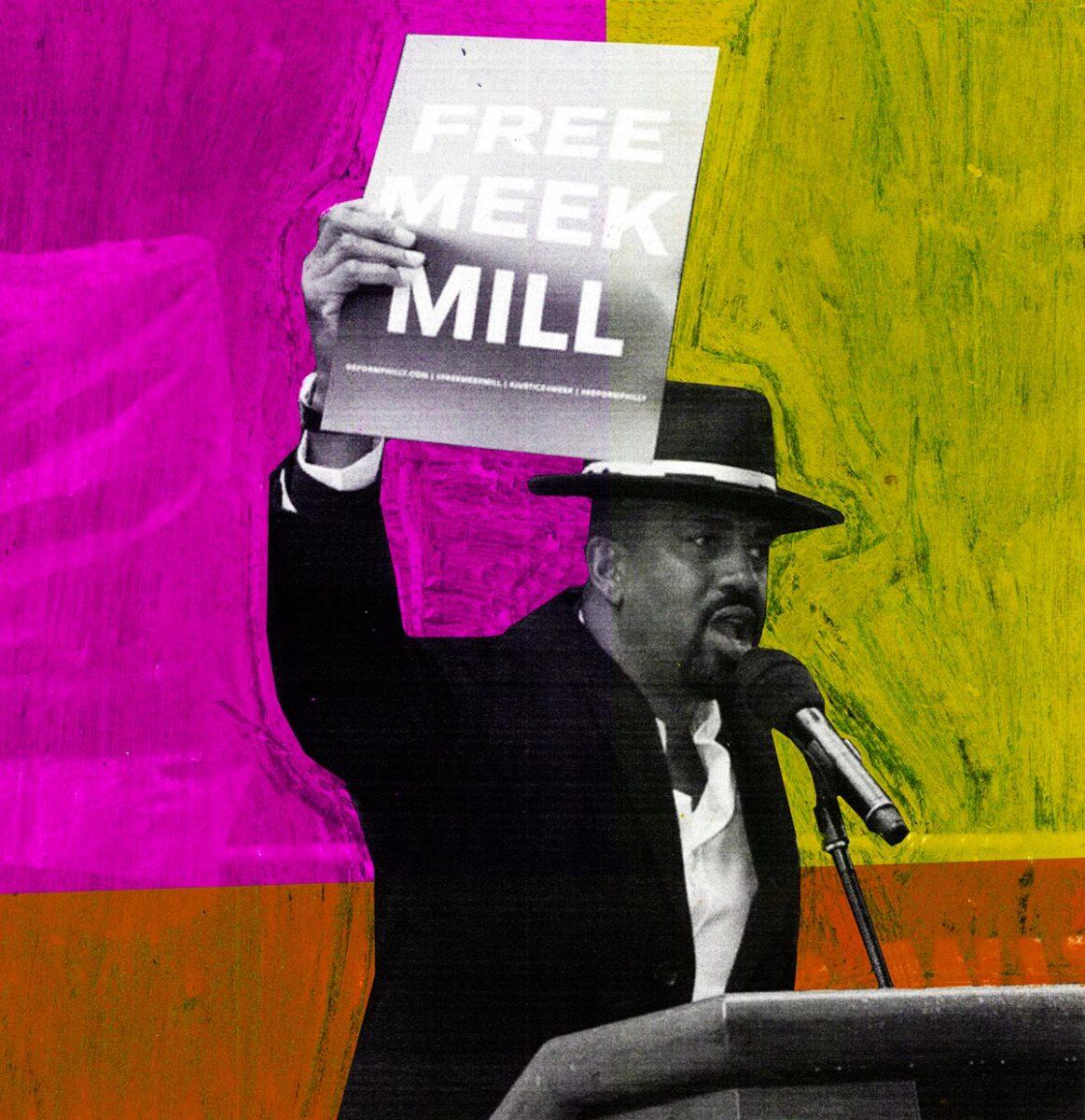

If Brinkley hoped to stay out of the spotlight, she failed. Her ruling sparked national outrage and unabating protest among Philadelphians, artists, and athletes — in late 2017, Jay-Z penned a New York Times op-ed about Meek, decrying probation as a “trap” and urging a “fight for Meek and everyone else unjustly sent to prison.” And on February 4, the Eagles entered the Super Bowl to Meek’s song “Dreams and Nightmares.”

Far from the Eagles’ triumph at the Super Bowl in Minneapolis, however, Meek’s legal team scored a new victory. Officer Walker again provided information about alleged misconduct by Officer Graham — this time directly to his attorneys. In a February 7 sworn affidavit, Walker said that Graham bragged, “I arrested that rapper boy Meek Mill and whooped his ass … I put a two-inch part in that bull’s head he’s gonna remember for the rest of his life.” More critically for Meek’s case, Walker said that the Jan. 24, 2007 arrest report “bears the hallmarks of a fraudulent affidavit, written to manufacture probable cause for the search warrant.” Walker zeroed in on Graham’s vague description of the drugs Meek allegedly sold that day — “small objects” — as well as Officer Sylvia Jones’s claim to have observed an informant purchase drugs from Meek at 22nd and Jackson streets which Walker said was not possible from her vantage point.

Defense counsel may have never learned about the extent of Graham’s misconduct if Philadelphia voters had not swooped reform-minded former civil rights attorney Larry Krasner into the district attorney’s office last November. Shortly thereafter, Krasner discovered the “do not call” list, and unlike his predecessor Williams, this March released the list of 66 officers, along with summaries of their wrong-doing. (The existence of the list, including the names of some of the police offenders, was leaked to the press in February.) Twenty-nine of those officers, including Graham, have been responsible for hundreds of arrests. And a prosecutor working in Krasner’s office, Liam J. Riley, conceded in a March 14 court filing that no prosecutor had ever alerted Meek’s defense attorneys to their lack of faith in Graham’s integrity and veracity.

In a case where the government presented Graham as its sole witness, evidence that prosecutors considered him so untrustworthy he could never testify threatens to blow Meek’s conviction wide open.

Epilogue

Meek’s case has questionable trial tactics, an overly invested judge, extensive police corruption, and enormous criminal justice system resources expended on a gun and drug charge that left him with an original maximum 23-month sentence. There is also the financial cost to Meek himself with the rapper spending upwards of $30 million on legal fees and wages because he could not travel and work. “Injustice has taken 11 years of our lives,” Meek’s mom recently wrote in an open letter published in Billboard. But Meek’s lawyers are fighting back, and they may now have a chance — albeit likely not before Brinkley.

Meek’s attorneys have requested that Brinkley recuse herself from the case, accusing her of showing personal bias toward their client. They’ve also filed the PCRA petition attacking his initial conviction, arguing that if a jury knew about Graham’s extensive corruption and dishonesty, it would never have convicted him in the first place.

A PCRA hearing has yet to be held and therefore there is no ruling from Brinkley on the petition. But she tipped her hand in late March when she denied Meek’s motion for release pending a ruling on the PCRA and for further discovery. Brinkley found it unlikely Meek would succeed on the merits, barely addressing the allegations against Graham, the government’s sole trial witness.

Meanwhile, the judge has hired her own attorney, Charles Peruto Jr., who has threatened to sue Meek and his lawyers if they refuse to issue an apology over negative press she has received or if they file a complaint with the Pennsylvania Judicial Conduct Board. It is rare for a judge to hire an attorney to speak about a matter pending in her court, but Peruto is not holding back: “[Brinkley’s] reputation has been severely damaged within the last month,” he said in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “We absolutely believe she has an absolute solid [defamation] case.”

But Brinkley will not have the final say. Meek’s legal team has filed several appeals in the case with the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, asking the Supreme Court to remove Brinkley from the case and grant him a new trial, and to reverse Brinkley’s decision to send Meek back to prison. This morning, they promised to file yet another appeal given her refusal to release Meek after the DA supported a new trial.

Appeals are rarely granted. But this is no ordinary case, and Meek has the backing of a powerful group that includes his expansive legal team, the Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf, Krasner (who has repeatedly reiterated his support for Meek’s bail), and New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft who visited Meek in prison on April 10 and said, “This guy is a great guy. Shouldn’t be here. And then think of all the taxpayers here paying for people like this to be in jail and not out being productive.” And at the PCRA status hearing in Philadelphia today, the Justice League NYC held a rally and sit-in for Meek outside the courthouse “to demand that Judge Brinkley overturn the original conviction … that was the result of police misconduct during his arrest over ten years ago.” Yet even with this formidable push for freedom, Meek could lose and serve out his two- to four-year sentence for a minor probation violation a decade after the initial offense.

It is hard not to think about other defendants, with cases marred by dirty cops and harsh judges, but without money, lawyers, or fame. If Meek loses his appeals, who can win?