The Path To Liberation Does Not Go Through Pretrial Punishment

Leaving power with the same actors, who equate safety with mass criminalization and detention, will yield the same results.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

On Monday, a caller to the Brian Lehrer Show expressed his discomfort with the current debate about recent bail reforms in New York. The caller, a lawyer from near Lake Placid, New York, had this to say:

“I think the biggest problem that bothers me the most with this is that it’s not intellectually honest … What we’re talking about here is not bail. It’s preventive detention and we ought to bring it out and debate it.”

Preventive detention, the incarceration of someone because of a belief they pose a threat to others, was, not so long ago, a disfavored idea. A generation ago, wrote Sandra Mayson, a law professor at the University of Georgia, in 2018, “critics argued that no probability of future crime was sufficient to authorize preventive detention.”

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of pretrial preventive detention in United States v. Salerno. Mayson described how “Justice Rehnquist, writing for the majority, concluded that none of the constitutional provisions invoked by the defendants categorically prohibits preventive detention.” Nevertheless, the Court affirmed that “[i]n our society liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception.”

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s insistence on pretrial detention as a “carefully limited exception,” the number of people held pretrial has ballooned. The abolition of cash bail has been a high priority. But for some, that has meant opening the door to so-called “dangerousness” assessments.

In a letter to Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo and political leaders yesterday, over 100 groups in New York argued that the state should not capitulate on recent bail reforms to allow for judges to order pretrial detention on the basis of these assessments.

“Adding ‘dangerousness’ to the bail law would codify racial profiling into pre-trial detention decisions,” the letter reads. “It is an invitation for bias … People of color would overwhelmingly bear the brunt of this misguided approach. According to a 2016 study, Black people were twice as likely as white people to be misclassified as ‘high risk.’ White people, meanwhile, were misclassified as low risk 63.2 percent more often than Black people,” reads the letter, as reported by the New York Daily News.

In a forthcoming essay, for the Law and Political Economy blog’s ongoing series on money bail, Mayson questions the legitimacy of a pretrial preventive detention system. “Absent money bail, we must make intentional decisions about when to restrict a person’s liberty to mitigate risk,” she writes. “But what degree of risk—of what kind of harm—is sufficient to justify depriving a person of liberty? Is the answer different for an accused person than for anyone else? As I have argued elsewhere, there is no reason that it should be different. If we take the presumption of innocence and prohibition on pretrial punishment seriously, there is no reason that the threshold of risk that justifies detention should be any different for a defendant than a member of the public at large. If this conclusion is uncomfortable, it should lead us to ask whether we are in fact willing to value the liberty of accused people in the same way we value our own.”

It is worth saying again: To be sent to jail in America is punishment. Jails are sites of suicides, overdose deaths, violence (including by government employees), and sexual assault. And that is in addition to the separation from family, children, parents, schools, home, and work. The emphasis on money bail should not obscure the larger goal. A system of pretrial detention that sorts on the basis of money is not the only problem. The problem is incarceration and in America, it happens all the time, to millions of people.

Mass pretrial detention is an end run around the presumption of innocence. For punishment purposes, it brings arrests closer to convictions. New York’s bail reforms, over the past many years, have been steps away from this, lowering pretrial incarceration while crime rates continued to drop. The reforms that went into effect this year are another step in this direction. To roll them back and institute a new system of pretrial detention is not the answer.

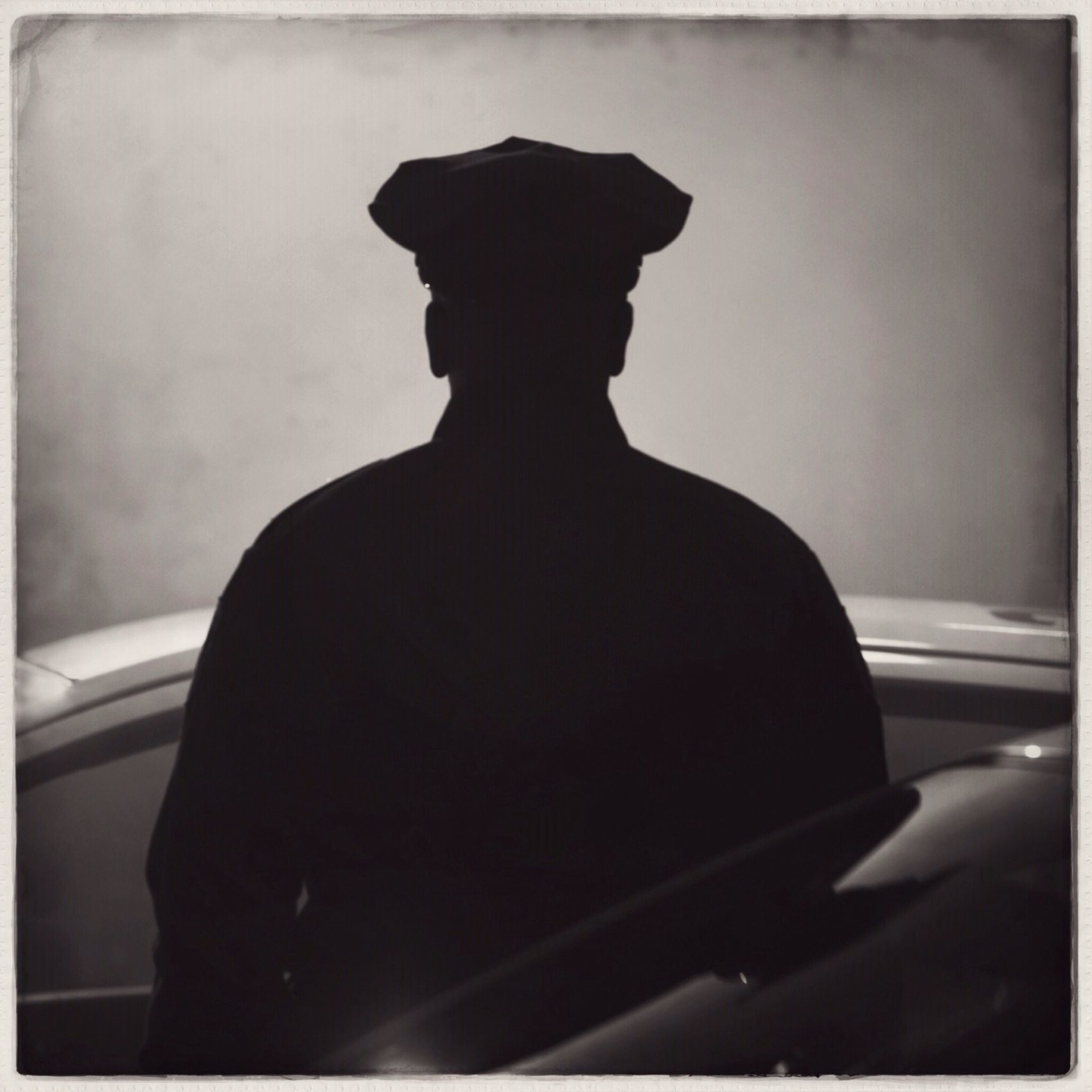

Such a system gives enormous power to remove people from free society and imprison them to one set of actors: the police. Is it any wonder they are among the biggest opponents of recent bail reforms in New York? Absent a default of pretrial release, the scale of arrests shapes the scale of jail admissions. A lengthy criminal code, stuffed with charges that criminalize poverty and need, has given officers the power to exercise control over people based on neighborhood, race, and class. Any restriction on pretrial detention restricts that police power.

In New York city, where the blowback against bail reform has been furious and sustained, not a single police official is an elected official (Sheriffs in some upstate counties are elected). Yet these officers view themselves, not just as enforcers of law, but as arbiters of what the law should be.

They also want to both represent the power of the state yet take umbrage at criticism that is too pointed or is profane. Contrast police reactions to the use by protestors of the phrase “F*** the police,” in a demonstration two weeks ago, going so far as to claim it incited the shooting of officers a week later, with the language of a police union head, who described the man arrested for the shootings as a “mutt.” This is a phrase that appears to be part of the NYPD vocabulary. Also consider police union officials declaring “war” on New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio.

The most generous interpretation of law enforcement opposition to restraints on pretrial detention is that law enforcement officers are more focused on what they view as their duty to protect than on people’s rights and freedoms. Implicit in this, however, is that police and prosecutors see themselves as protecting a group of people separate and apart from those who need protection from incarceration itself. This means acknowledging that law enforcement does not view protection from harm at Rikers Island and other jails across the state, as something they should deliver, or even consider.

If you believe one group of people needs to be controlled, is per se dangerous, and that social policy needs to be set accordingly (cue the Michael Bloomberg defense of stop-and-frisk in a 2015 tape that was recently leaked), then the encounter on the street is preordained. Similarly, a society that decides jail is a necessary means of social control will find a way to funnel people into jail. The question is whether we have ideas for safety that go beyond incarceration. A different society, one in which Black and Latinx people were not treated as threatening, and which decided healthcare, housing, and education were basic rights, would not need to define so much as criminal in order to enforce that criminalization against some people.

The point is not that the rich should be jailed the way the poor are. The point is that jail is not the path to safety. Eliminating money bail is part of the path to eliminating pretrial detention and that is part of the path to collective liberation.