The Past, Present, and Future of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office

The DA’s office has been home to bribery, corruption, and more since it was formed 170 years ago. What could a progressive prosecutor do to change that?

As people across the country cry out to overhaul policing, the calls for defunding district attorneys ring softer. Yet prosecutors play a major part in upholding systems of policing and incarceration.

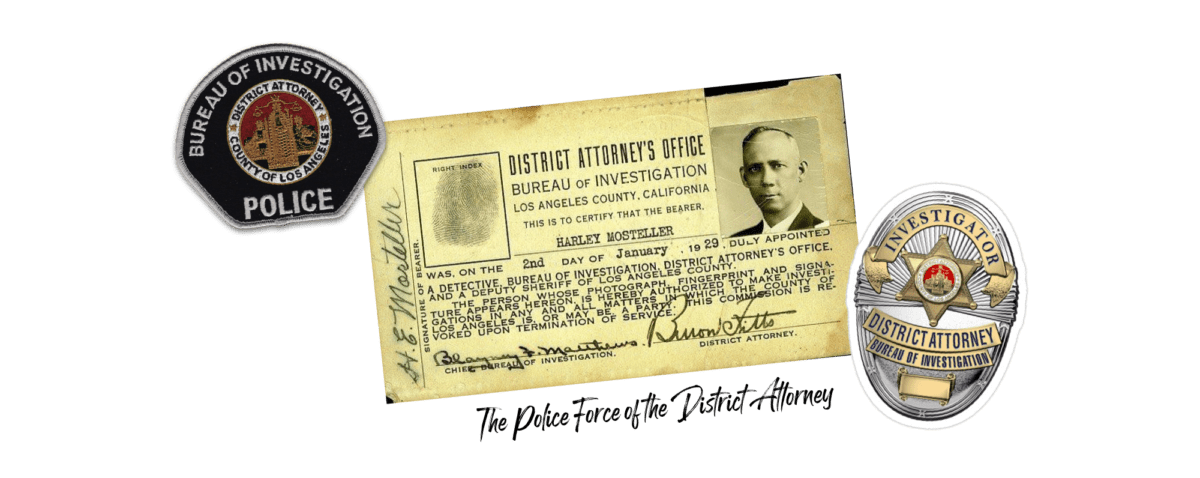

District attorneys are often mentioned in the media, but their role is rarely explained. They are not merely receiving cases to try. They are both part of law enforcement and work with law enforcement. Their investigators have the same powers as police officers. They develop predictive crime units. They decide who to prosecute and what the charges are. They also lobby for or against laws.

As history shows, there has never been anything impartial about this highly political role.

The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office—the largest in the country—is no different. Los Angeles has an opportunity to redefine what progress in a prosecutor’s office could look like for other prosecutor offices around the country.

Although LA County’s current district attorney, Jackie Lacey, has taken a lot of criticism for wielding the law in fatal and unequal ways, she is also a product of a flawed machine. The DA’s office has been home to bribery, corruption, lies, manipulation, and even murder since its formation. The question now is what should happen next and who is willing to make positive changes.

The Role of the Los Angeles DA

The district attorney is a prosecutor who represents the state and the county. That person is responsible for deciding when to bring charges against someone, what those charges are, and for winning convictions.

But lawyers can also be politicians. The district attorney, like the city attorney and the attorney general, is an elected position. The United States is the only country that elects prosecutors.

The LA district attorney’s office oversees criminal cases for LA County, with some exceptions. Its prosecutors handle all county felonies like murder, arson, burglary, forgery, and the sale of illegal drugs. They also handle smaller crimes, or misdemeanors, for most of the cities in the county with the notable exception of the city of Los Angeles.

The DA’s work extends past the courtroom. The office collaborates with law enforcement, sometimes embedding prosecutors at police stations; investigates crimes, sometimes at the crime scene; investigates any complaints about law enforcement and crimes committed by law enforcement; and offers services to victims, though they do not represent them.

Where the DA’s office is most indistinguishable from the police, though, is in its ability to develop special units. In LA County, the office has several special units like the Hardcore Gang Division and the Organized Crime Division, which target people to prosecute and incarcerate, sometimes with no evidence that they have committed a crime.

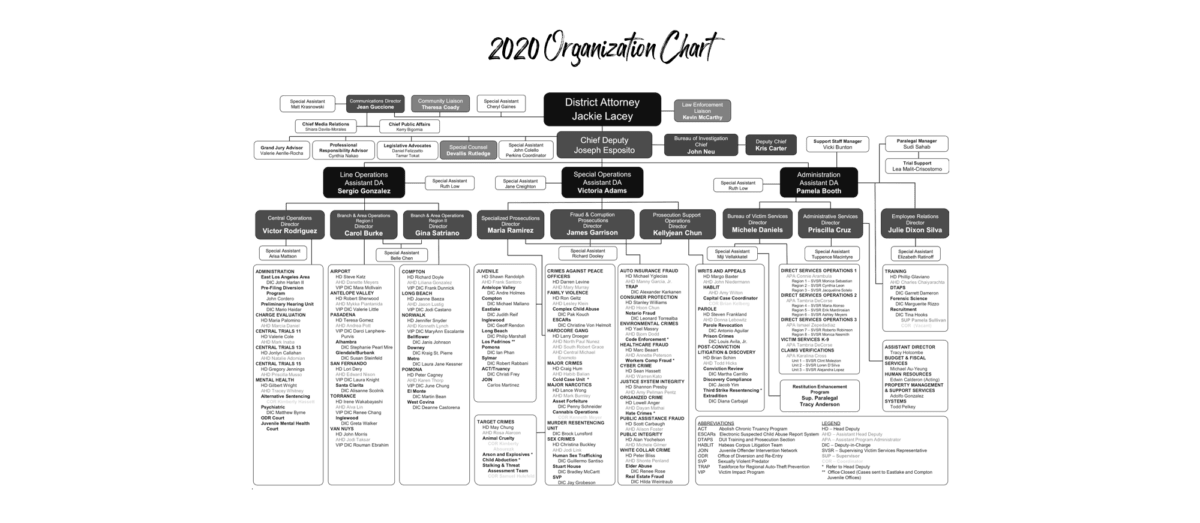

The Los Angeles DA’s office has a couple thousand employees broken down into three main categories: deputy DAs, DA investigators, and support staff.

Deputy DAs work under the guidance of the DA and in collaboration with law enforcement to bring charges and prosecute crimes. Deputy DAs often run for judgeships.

DA investigators work alongside the deputy DAs to gather evidence, find witnesses, and conduct investigations to aid cases. They may conduct independent investigations but mostly work to augment law enforcement, including collaborating with federal agencies like the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Secret Service and the U.S. Marshals. When an officer shoots someone, DA investigators and a deputy DA are among those who respond to the scene.

There are about 1,000 deputy DAs, 300 DA Investigators and 800 support staff members.

It’s worth noting that the LA public defender’s office, which provides legal representation to defendants who cannot afford lawyers, has half the staff and half the budget of the DA’s office, even though the office has a higher caseload.

The History of the Los Angeles DA’s Office

The LA district attorney has historically reinforced the idea that crime is inevitable and can only be handled with carceral consequences.

But the motivations of Los Angeles DAs have been varied and often immoral. William C. Ferrell was the county’s first DA in 1850, and his salary was augmented by winning cases. It wasn’t very lucrative when people weren’t found guilty. When his caseload was cut by the state legislature, Ferrell’s salary was also reduced, so he resigned. Isaac Ogier, the county’s second DA, was a founder of The Rangers, a vigilante mob. It is documented that they lynched at least 22 people. After serving as DA, Ogier went on to become a U.S. attorney and a federal judge.

The LA DA’s office has also been home to white supremacists who fought to preserve slavery. At least two of the county’s earliest DAs pledged their allegiance to the Confederacy. Cameron Thom, who had three separate terms as DA, went back to the South and fought in the Confederate Army between terms. He also lobbied in the California state legislature to allow for the enslavement of Black people under the age of 21. A few years after Thom’s first term, former DA Edward J.C. Kewen was briefly imprisoned on Alcatraz for his publicly Confederate views.

By the 1900s, Los Angeles DAs had built an engine for convictions and had sold the public on the idea that this meant justice and safety. Yet behind closed doors, some DAs were making deals and offering favors.

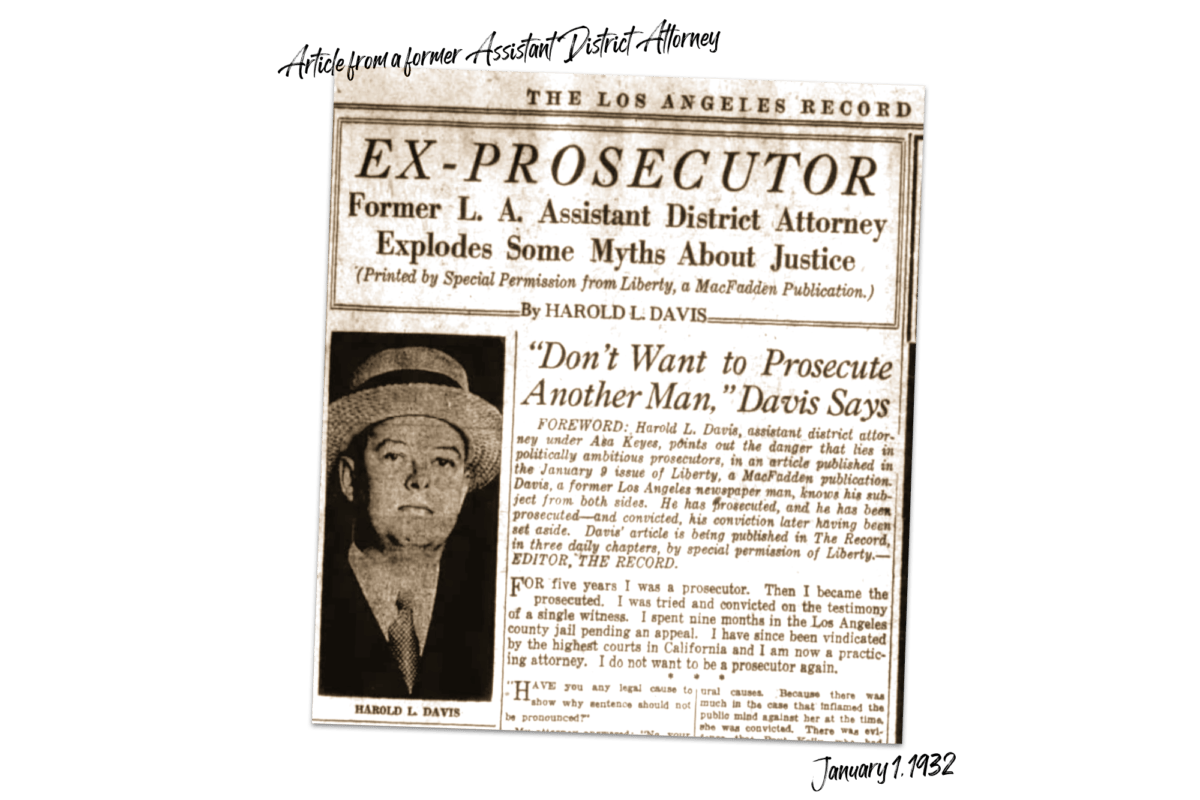

In 1929, DA Asa Keyes was convicted of accepting bribes to acquit executives in the Julian Petroleum Corporation scandal. One of Keyes’s deputy DAs, Harold L. Davis, was also convicted of bribery. Davis published a change-of-heart, tell-all article in the Los Angeles Record, writing, “I watched the selection of a jury, and for once I hoped the jurors would not be tools of the district attorney. I saw and recognized all the familiar tricks of a prosecutor used against me.”

Buron Fitts took over for Keyes. After prosecuting both Keyes and Davis, Fitts and his sister were indicted on bribery and perjury related to dropping a friend’s charge of statutory rape. Fitts was acquitted and his sister’s charges were dropped. He continued to serve as DA until 1940.

Tough on Crime, Soft on Cops

Los Angeles DAs have prosecuted each other, but it is strikingly rare how often they have prosecuted the police.

Jorge Gonzalez, a longtime civil rights and criminal defense attorney who has been involved in several cases where the police have killed people, told The Appeal it’s because district attorneys and law enforcement are on the same side. They drink a Kool-Aid that turns people into “true believers” who hold that the system can do no wrong, he said.

One of the rare cases in which a DA has prosecuted police officers was that of Rodney King in 1992. DA Ira Reiner prosecuted the four officers who brutally beat King, but they ultimately were acquitted. Many historians believe this was because the trial venue changed, which resulted in a mostly white jury. When Reiner ran for re-election, he lost to Gil Garcetti and dropped out of politics entirely.

In the late 1960s, when Garcetti was a deputy DA, he helped establish a unit that sent a prosecutor and investigator to the scene when a police officer allegedly shot someone. But once elected in 1992, he quietly cut the unit. “I’d rather be prosecuting violent criminals than going out and ratifying that police officers did not commit improper shootings,” he said once in office. The unit had been investigating approximately 200 cases a year at that point.

Since Jackie Lacey took office in 2012, there have been over 600 police shootings in LA County. Like many prosecutors, Lacey has said that the law ties her hands when it comes to prosecuting police for fatal use of force. Under California law, a police officer can legally kill someone if they reasonably believe that their life or someone else’s life is in danger or they feel that the person could cause someone serious bodily harm.

Critics say Lacey’s reluctance to prosecute cops is tied to the support that her campaigns have received from police unions and law enforcement special interest groups.

Even in cases when police shootings have been found to be out of policy by civilian oversight groups and the chief of police, Lacey wouldn’t file charges against officers. She didn’t charge the Los Angeles Police Department officer responsible for fatally shooting Brendon Glenn in 2015 after Chief Charlie Beck recommended that the officer be prosecuted.

And Lacey has appeared to accept police narratives without digging further. While the LAPD Board of Police Commissioners determined in its report that the 2018 shooting of 30-year-old Albert Ramon Dorsey was lawful, it also found that “the tactical decisions made by [Officer Edward Agdeppa] leading up to the use of deadly force were at odds with tactical training.” The report also noted that officers used profanity, failed to coordinate with the 24-Hour Fitness Center at which the shooting occurred, and never called for backup. Still, Lacey did not pursue the case; she declined to charge Agdeppa this summer.

On Tuesday, LA County voters will decide between Lacey and George Gascón, a former LAPD officer turned prosecutor who resigned from his position as San Francisco’s district attorney to run in Los Angeles.

Although Gascón has positioned himself as a “justice reform advocate,” both he and Lacey have been criticized for their failure to prosecute police. Lacey has only prosecuted one law enforcement officer for a fatal shooting during her tenure and Gascón didn’t prosecute any when he was San Francisco district attorney.

Despite Gascón’s similar track record when it comes to prosecuting police, he gives reformists more hope than Lacey. He co-authored Proposition 47 which reduced some nonviolent offenses (like drug possession) from felonies to misdemeanors, thus keeping some people out of prison. Gascón has also pushed to reform laws that protect police from prosecution, and he’s said that he’ll reopen notable use-of-force cases if he’s elected, including Glenn’s.

The Future of the DA’s Office

Gascón might reopen some use-of-force cases, but what happens to less notable ones?

In March, Lionel Morales was at a strip mall in Historic Filipinotown when a car backed up and ran over his leg. The driver fled but Lexis-Olivier Ray, one of the writers of this story, got the driver’s license plate number and reported it to LAPD Central Traffic Division the next day. Morales, then homeless, was in a hospital and then a nursing home for weeks, before he returned to the streets and connected with Ray.

Ray gave police the victim’s name and contact information, handed over the driver’s license plate number and a short video of the driver fleeing, and identified the driver in a photographic lineup. But the district attorney’s office rejected the case. According to a “charge evaluation sheet” from the office obtained by Ray, the DA declined to charge the driver in part because prosecutors “couldn’t locate” the victim.

“How could that be?” Morales said when Ray broke the news to him in October. In April, Morales had secured a temporary hotel room through Project Room Key—a program to house the unhoused during the COVID-19 pandemic—after Ray publicized what happened to Morales on Twitter and a coalition of doctors from the VA Hospital, staff members from Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell’s office, and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority responded.

The conviction rate for hit-and-runs in Los Angeles is low. Between 2014 and 2018, according to Curbed LA, the district attorney’s office won convictions in 169 out of over 23,000 felony cases.

“There’s a whole culture around winning,” John Raphling, a former defense attorney who represented the family of Brendon Glenn, said of why prosecutors don’t take up these kinds of cases.

But even if Morales’s case was re-examined, he still has a lot of other hurdles to overcome that can’t be solved through punishment. Putting the driver in prison isn’t going to repair what happened to his leg, it’s not going to put a roof over his head, and it’s not going to get him the medical help that he desperately needs.

“There’s a reward system for being harsh, there’s no thought of ‘what is the impact on the victim, on the victim’s family, on the victim’s community?’” Raphling said. “It’s ‘we’re protecting society by locking this person up.’ The role of the DA is not really conducive to problem solving.”

District attorneys have weaved a deep narrative about what keeps us safe. But there’s a new culture emerging with prosecutors like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, Kim Foxx in Chicago and Chesa Boudin in San Francisco. George Gascón counts himself among them. These prosecutors are considering options beyond prison, reducing sentences, and looking at wrongful convictions.

But how much progress can a “progressive DA” actually make? On a recent panel, Ivette Alé from the JusticeLA Coalition said, “It’s not about electing a better DA. It’s about deconstructing this system so we no longer rely on it. Electing a better DA is a harm reduction measure.”