Political Report

The Opioid Crisis and the Elected Sheriff

Sheriffs often control access to treatment in jail and shape law enforcement attitudes toward the opioid crisis. What are their roles?

This is the second installment of The Badge, a series on the powers of sheriffs. The previous one was on jail deaths.

Madison Jody Jensen was arrested for drug possession in 2016 and booked into the jail run by the Duchesne County Sheriff’s Department in Utah. As The Appeal has reported, she went through withdrawal in her cell, vomiting and defecating on herself, but she was denied the medical care she requested. She was later found dead from dehydration as a result of withdrawal. She had lost 17 pounds in the four days between her entry in the jail and her death.

Deaths like Jensen’s are not uncommon. As of 2017, Utah had the highest number of jail deaths per capita; it also has a serious opioid crisis, which mirrors a nationwide problem. One estimate shows that of the 10 million people processed through jails every year, approximately a quarter have opioid use disorder.

Jails are particularly dangerous places for people with opioid addiction. They put people who are on successful treatment regimens outside jail at risk for relapse, and they can provoke dangerous withdrawal symptoms, especially in light of the frequently inadequate access to medical care. People are in greater danger of overdosing and dying after incarceration.

While the legal system may not be the best place to address addiction as a health problem, the fact that users are being arrested, and that many still lack health insurance or access to community programs, makes treatment in jails essential to preventing serious and even deadly issues. Medical studies show that people treated while incarcerated are less likely to overdose after their release. But this also forces the issues of rethinking law enforcement attitudes toward substance use, and expanding access to alternative avenues to treatment.

As a result, sheriffs—as elected officials who control treatment in jails, shape law enforcement practices outside them, and influence broader local debates—are on the frontlines of the opioid crisis.

“Sheriffs have a choice,” Dionna King, policy manager with the Drug Policy Alliance, told the Political Report. “They can look at the people they are bringing in and decide it’s better for them to remain in the community where they can be in a treatment setting. But if they continue to arrest, they have to provide adequate healthcare.”

This installment of The Badge, an Appeal: Political Report series on the power of sheriffs, examines their role in the opioid crisis. It considers what’s at stake when sheriffs set their tactics and policies toward substance use treatment, and how sheriffs can promote better community-oriented solutions.

Law enforcement and the opioid crisis

Sheriffs who run jails control access to outpatient medical care, set treatment policies, and hire and train personnel. In communities where they are the primary law enforcement, sheriffs and their deputies are first on the scene when someone overdoses. They may also conduct investigations—pursuing both users and dealers—and, in some places, even assess the cause of death.

These overlapping roles—first responders, caretakers, investigators, jail security—can result in contradictory goals.

The legacy of the war on drugs is that law enforcement agencies interpret public health problems as criminal ones. Their harsh rhetoric and practices exacerbate stigma, and make treatment harder to obtain within or outside the criminal legal system.

First, sheriffs’ punitive approach triggers outsize drug busts that can by themselves wreak violence. And sheriffs are incentivized by civil asset forfeiture rules to act in this manner.

But putting people in jail carries risks. Because jails routinely fail to screen for addiction or to provide adequate medical care, going through withdrawal there is dangerous.

“Unmanaged withdrawal in jail is not just bad for patients and deadly, but it’s terrible for people working there or for other inmates,” Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University School of Law, told the Political Report.

There were at least 27 jail deaths in Utah in 2016, including Jensen’s, and some have been linked to withdrawal symptoms and opioid use disorder. But as of late 2018, many jails run by the local sheriff’s departments still provided no withdrawal drugs to people detained there, according to a report by the Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. Despite being released by the state, this report provided incomplete information on deaths and treatment, in part because of poor disclosure and data collection by the counties. This is a problem that plagues efforts to remedy jail deaths nationwide.

In addition, people exiting incarceration are at a higher risk of dying after their release.

“Discharge from jail or prison is a chaotic, unstable time,” Dr. Kimberly Sue, medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, told the Daily Appeal in an email in March, “and if patients have lost opioid tolerance as a consequence of jail policies in combination with a toxic street supply (fentanyl in the heroin or other drugs including cocaine), this could equate to significantly increased chances of overdose and death upon release.”

“War on drugs”-style law enforcement causes other problems. Witnesses to an overdose may hesitate to call for emergency help if they are concerned about being arrested. The growing trend of prosecuting people for homicide in the aftermath of overdoses exacerbates this issue. Sheriffs do not determine criminal charges, but those who wield investigatory powers can support such policies. In Florida, Flagler County Sheriff Rick Staly says he instructed his deputies to investigate overdose deaths as murder cases. The local state attorney credited an investigation by Staly as enabling the county’s first-degree murder charge.

As opioid deaths have soared, so have questions about how sheriffs should use their power and resources. Should they administer addiction treatment, and what kind? Should communities invest in building a new jail or a mobile clinic? What is a sheriff’s responsibility toward public health beyond making arrests?

Providing treatment

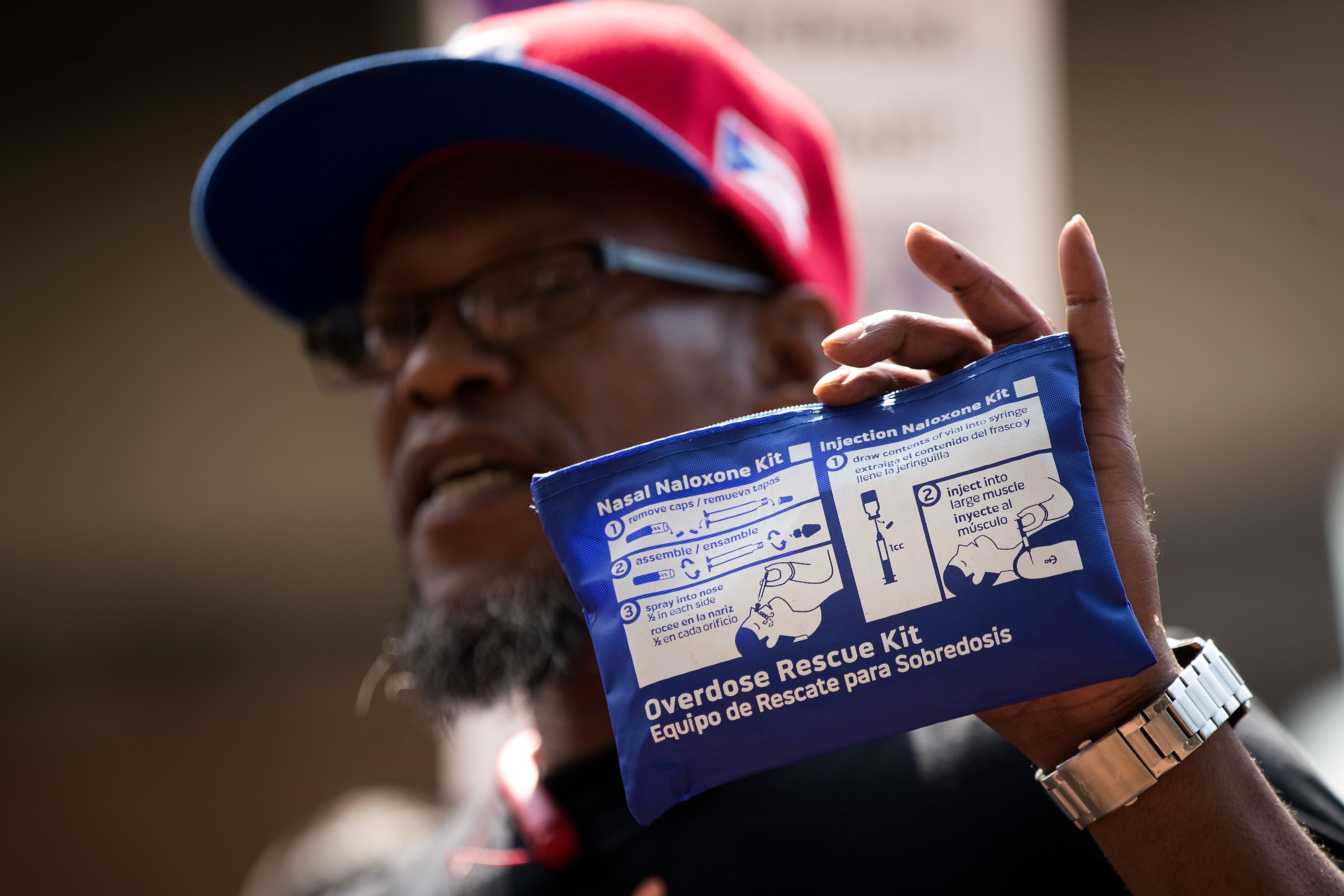

A medication-assisted treatment (MAT) protocol that incorporates buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone with counseling and behavioral therapy has been cited in a U.S. surgeon general report as the “gold standard” for treating opioid use disorder. This combination matches the recommendations of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Sheriffs’ Association, which released new guidelines for sheriffs in October 2018. Buprenorphine and methadone are opioids that lessen withdrawal pain and ease cravings; naltrexone blocks opioids from having any effect for a month. Another relevant medication is naloxone, or Narcan, which quickly reverses overdoses.

But in counties where sheriffs run jails or have policing duties, it is typically still up to them whether to carry and provide these treatments. Many do not.

Sheriff’s deputies can be first on the scene of an overdose, and they can help reverse it—if they are carrying naloxone. This is especially crucial in rural areas where emergency medical services may be delayed.

Treatment decisions also matter a great deal within jails. “Jails have people going through active withdrawal,” said Beletsky. “We need to make sure we can get to those folks right there and then.”

Last month, a group of 58 current and former law enforcement officials—including eight sitting sheriffs—signed a letter in support of expanding access to MAT, providing naloxone, and connecting people to post-release care. “We recognize that this epidemic of drug overdose requires a new approach,” the letter states.

One of these eight sheriffs is Joe Pelle of Boulder County, Colorado. He told the Political Report he had seen a “change in attitude toward addiction.” Everyone “gets it” now, he said, “when we do something to reduce recidivism and reduce substance and mental health problems.”

Another is Albany County Sheriff Craig Apple. In January, he became the first New York sheriff to provide people in jail access to each of the three core MAT drugs. In an interview with the Political Report, Apple explained further that “it was really a compassion and mercy thing. … If you are truly in the game to help people, you can do it.”

But many sheriffs resist these changes.

Some sheriffs think MAT is enabling and substitutes one drug for another. Sheriffs also say they fear MAT introduces “contraband” into jails and creates an underground market. But Apple argues that when sheriffs provide MAT, it can actually make for more regulated environments in jails. “We don’t have them calling family begging them to smuggle in treatment,” he told the Political Report.

In Massachusetts, Essex County Sheriff Kevin Coppinger refused to let people in jail continue buprenorphine or methadone treatment. “In a prison setting,” he said in a statement, “administering these drugs raises many security, logistical, and fiscal concerns that are not issues for individuals who are not incarcerated.” A federal judge ordered in November that he allow one man access to methadone treatment.

At times, the decisions made by sheriffs reflect whether they think it’s the job of government to look after people with substance use disorders. Take Ohio’s tale of two sheriffs: The Associated Press reported on the contrast between Clermont County Sheriff Steve Leahy, who has instructed his deputies to carry Narcan to counter overdoses, and Butler County Sheriff Richard Jones, who has not. Jones has argued that overdosing is a matter of choices made by drug users. But for Leahy, “no matter what their plight is and how they got to where they are, it’s not for us as law enforcement to decide whether they live or die.”

Some advocates have turned to courts or legislatures to circumvent reluctant sheriffs, and lawsuits demanding that jails provide MAT have multiplied. Sally Friedman, of the Legal Action Center, told the Boston Globe in November that the decision against Coppinger was “the first time a court … has ruled” that failure to provide MAT “can violate the ADA [American with Disabilities Act] and the Constitution.”

Similar rulings have followed. A federal judge ruled in March that the sheriff of Aroostook County, Maine, must provide MAT to Brenda Smith, a woman sentenced to 40 days in jail who had been taking medication to help with opioid addiction for years. The jail planned to not let her continue her treatment, effectively forcing her into withdrawal. “Given the well-documented risk of death associated with opioid use disorder, appropriate treatment is crucial,” wrote U.S. District Judge Nancy Torresen. “People who are engaged in treatment are three times less likely to die than those who remain untreated.”

An additional obstacle is that local resources to pursue MAT can be scarce. “There is a cost attached to this care,” said King. “More rural places may not be able to pay for these products.” Indeed, the opioid crisis has hit rural communities hard, but rural jails have fewer financial and medical resources. In some rural counties, there are no licensed doctors to prescribe MAT at all.

State governments can facilitate access and resources for medication and counseling. The Massachusetts legislature is starting a pilot program to help jails set up treatment protocols and get funding; Coppinger asked to join the program soon after losing the lawsuit.

Treatment inside and treatment outside

Jails and prisons are becoming hubs that connect people to treatment plans. But there is cause for concern about relying on the criminal legal system to do this work.

King said that relying on the legal system to provide access to treatment is a “double-edge sword.”

People should get treatment while incarcerated, King said, but jail programs cannot be “a justification for net-widening to do some form of involuntary or coercive treatment.” Sheriffs and other local officials have touted the addiction services in their jails as reason to be wary of decarcerative policies.

Sheriff Shaun Golden of Monmouth County, New Jersey, has argued that the state’s bail reform has stymied addiction screening and connections to rehabilitative programs because it reduces the pretrial incarceration of people who are arrested for low-level offenses and who before may have stayed in jail for weeks.

But even a short stay in jail puts individuals at risk, including suicide.

Instead sheriffs can boost public health approaches that take place away from the legal system and enable people with addiction to remain in their communities.

Some sheriffs have partnered with community health providers, for example through initiatives that connect people with local treatment resources without arresting them. Sheriffs also pursue discharge planning to facilitate continued treatment or housing through community services. “The best practice is to bridge community care and correctional care,” Beletsky said. In Massachusetts, Middlesex County Sheriff Peter Koutoujian has implemented a MAT program that defines treatment as “the ongoing healthcare services and network of support that navigators are able to assist with post release.”

Assisting with treatment outside the jail can prevent people from entering the correctional system in the first place, or from falling in a cycle of reincarceration.

Sheriffs can also support harm-reduction strategies by local health departments, such as needle exchange programs (Sheriff Ronnie Oakes did so in Wise County, Virginia), or else advocate for more affordable health insurance. Studies have found that expanding Medicaid alleviates opioid mortality, and that states that have done so increased access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Improving medical care in this way does not cut into correctional budgets, and it helps people with addiction issues without creating a demand for a larger criminal system.

Last year, the Idaho Sheriffs Association endorsed the state initiative to expand Medicaid, calling expanded health coverage a way to “keep people out of the jails” and alleviate costs for rural jails. One of the initiative’s organizers, Luke Mayville of Reclaim Idaho, told the Political Report in November that Medicaid gave “people a way out of addiction and the incarceration that comes with it,” and that the sheriffs association’s endorsement “was a big boost.”

“They’ve seen the extent to which drug addiction problems are interwoven with criminal justice and incarceration,” Mayville said of Idaho’s sheriffs.