The LAPD Has a New Surveillance Formula, Powered by Palantir

Los Angeles Police Department analysts are each tasked with maintaining “a minimum” of a dozen ongoing surveillance targets for future targeting, using Palantir software and an updated “probable offender” formula, according to October 2017 documents, obtained through a public records request lawsuit by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and given exclusively to The Appeal. These […]

Los Angeles Police Department analysts are each tasked with maintaining “a minimum” of a dozen ongoing surveillance targets for future targeting, using Palantir software and an updated “probable offender” formula, according to October 2017 documents, obtained through a public records request lawsuit by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and given exclusively to The Appeal.

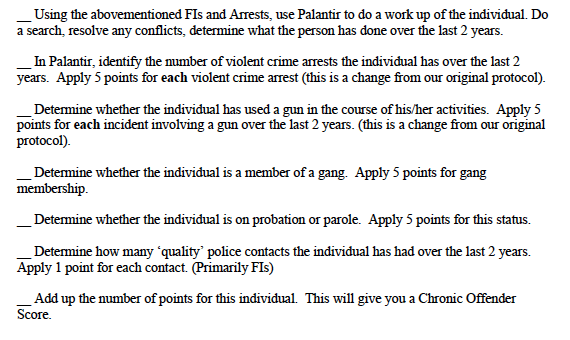

These surveillance reports identify “probable offenders” in select neighborhoods, based on an LAPD point-based predictive policing formula. Analysts find information for their reports using Palantir software, which culls data from police records, including field interview cards and arrest reports, according to an updated LAPD checklist formula, which uses broader criteria than the past risk formula the department was known to have used. These reports, known as Chronic Offender Bulletins, predate Palantir’s involvement with the LAPD, but since the LAPD began using the company’s data-mining software in September 2011, the department claims that bulletins that would have taken an hour to compile now take “about five minutes.”

Los Angeles police argue that targeting “chronic offenders” in this manner helps lower crime rates while being minimally invasive. But the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, a community-based alliance that has advocated against increased LAPD surveillance efforts since 2012, paints a different picture of the Chronic Offender Bulletin program. The group calls it a “racist feedback loop” in which police surveil a set number of people based on data that’s generated by their own racially biased policing, creating more monitoring and thereby more arrests.

Field interview cards, for example, which provide information for the predictive checklist, often result from on-the-street racial profiling, argues Jamie Garcia, the lead organizer on the Predictive Policing campaign with the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition. “When we look at LAPD stops, the black population is completely overrepresented,” said Garcia in a phone call. The directives, she says, direct officers “to find these people and to basically harass them…. If you’re constantly being surveilled, constantly being harassed, the chance of something going wrong … The next thing you know, you’re a chalk outline.”

Legal scholars have noted that the institutionalization of risk formulas like the LAPD’s Chronic Offender program checklist can exacerbate existing patterns of discrimination by oversampling those already discriminated against, generating even more biased data that justifies further discrimination.

The LAPD declined The Appeal’s request for interview, and did not provide answers to written queries about the program. In an email to The Appeal, Palantir spokesperson Lisa Gordon confirmed that Palantir is used in the creation of Chronic Offender Bulletins, but stressed that the software does not automatically generate the reports and that the selection and vetting of people on these lists are part of “a human-driven process.”

How Pre-Crime Investigations Begin

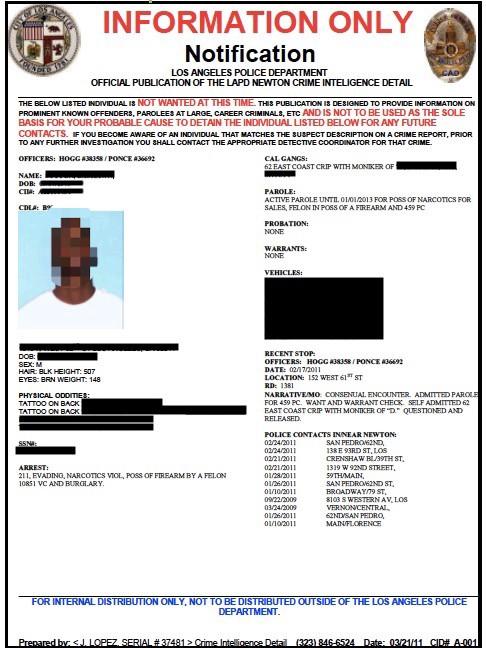

The target identification process starts with a LAPD analyst looking for “probable offenders” by surveying police records. According to the LAPD documents, analysts deploy Palantir’s file-organizing software to conduct “work-ups” of these individuals, looking for records that add points to their predictive risk scores, which are based on factors, such as whether they are on parole and their number of police contacts in the last two years. Below is an image of one of these “work-ups,” generated a few months before the department adopted Palantir, which The Appeal found online, completely unredacted, in a May 2013 LAPD presentation.

Adding up points based on police stops and other criteria outlined in the formula, an analyst would then create “at a minimum” 12 Chronic Offender Bulletins for high-scoring individuals, and identify five to 10 others as potential “back ups” for the target list. The 12, ranked by highest point values, are then referred to officers to ensure the targets are not already in custody or being tracked. As the documents state explicitly, these targets are, at this point, legally “not suspects but persons of interest.” A “person of interest” has no defined legal meaning, but can simply mean someone who might have knowledge about a crime.

Critics claim that this essentially creates a cycle where anyone who has any history with the criminal justice system can now be subjected to increased surveillance for the foreseeable future, even if they’re not suspected of having any connection to a recent crime. On the redacted work-up above, which the LAPD confirmed as authentic in an email, the individual had been stopped twice in a single day on four separate occasions during a six-week period. All these stops would count as points in the predictive formula, making him a higher priority for the surveillance program.

Though the LAPD claims such reports are “for informational purposes only and for officer safety,” the report information is then fed to an internal LAPD database “for tracking and monitoring purposes,” according to the 2017 documents. Armed with this data, such as where target offenders have been stopped and what tattoos they have, special LAPD units are sent out to “engage” targets with specified tactics, such as checks for outstanding warrants or illegal gun seizures, which may lead to arrests.

Sarah Brayne, a University of Texas at Austin assistant professor of sociology, who conducted field research with the LAPD in 2015, says that officers are keenly aware that the bulletins did not give them reasonable suspicion or probable cause. “The language used when I talked with officers was, “Go talk to them, and you might catch them doing something, but there’s currently no PC [probable cause].”

Though the LAPD documents do not explicitly state that those on the list must be arrested, they suggest that once an individual lands on a Palantir-powered bulletin, police are supposed to continue monitoring the individual until he or she is in custody. According to a released PowerPoint presentation, for example, officers are expected to ask themselves “how many chronic offenders have been arrested” in the previous two weeks and what their strategies are for “outstanding offenders.”

Every week, analysts too are supposed to determine whether the individuals on their target lists “are active or in custody,” and then replace those who have been captured with so-called “back-ups,” other individuals scored as high-risk, creating new targets for police to engage.

Individuals can be removed from the surveillance list if they have not had any police contact for two years, says Brayne, but the program’s underlying logic is to incapacitate those determined to be the main drivers of crime.

Given the amount of scrutiny and routine contact that officers are instructed to pursue for people on the bulletin list, avoiding all police contact is not realistic, says Josmar Trujillo, an anti-gang policing activist in New York. “If you live in a community of color in America, you don’t have the choice of having these contacts,” said Trujillo in a phone call. “Oftentimes, you can be stopped just for being around certain people, whether it be car stops or stops of groups on a street, so this predictive policing idea that you have to earn your right not to be on the list is cruel because to avoid law enforcement for years — that’s not possible.”

Perverse Incentives?

The LAPD’s expectation that analysts have a minimum of a dozen targets on deck is possible thanks, in part, to the departments’ use of the software from Palantir, the controversial tech firm founded by libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel. As Craig Uchida, an LAPD consultant and research partner, told Wired, before Palantir was brought on board, LAPD analysts could not make enough surveillance bulletins to keep up with officer stops. At the time, he recalled, cops were stopping around 100 people daily in the South LA neighborhood the program was first implemented in, bringing in too much data for analysts to efficiently process.

The documents also suggest that LAPD brass have become more committed than in years past to fulfilling the Chronic Offender program’s goals for officer surveillance and “engagement” with those listed. According to the documents, at weekly crime control meetings, specialized units targeting offenders are supposed to give reports on “their progress” to date. Brayne says this is a relatively new development.

“There was definitely tracking of how many arrests, but that was largely to collect data to measure efficacy and make a case for continued funding,” she said.

The expectations, embedded in these predictive policing tactics, worries Garcia, who points out that such incentives could motivate or even force analysts and officers to make unfounded arrests just to check people off their bulletin lists. “So the LAPD is even surveilling itself,” Garcia said.

Brayne, on the other hand, pointed out that during her field work, officers had too many high-point offenders to deal with, not too few.

New Technology, Similar Victims

Activists also argue this predictive policing program could be giving new scientific and legal cover for traditional police practices in poor, non-white communities, viewed by some as racially discriminatory.

“The data is inherently subjective, and it has that implicit bias in it,” Garcia said, claiming that data drawn from raw police interactions necessarily bakes existing biases into the LAPD’s predictive risk models. And Brayne’s ethnographic findings about the culture of the LAPD suggests these concerns may be justified. “They say you shouldn’t create a — you can’t target individuals especially for any race, or I forget how you say that,” said one unnamed officer to Brayne, when asked why the department had shifted to its points-based surveillance system. “But then we didn’t want to make it look like we’re creating a gang depository of just gang affiliates or gang associates… We were just trying to cover and make sure everything is right on the front end.”

The documents also reveal a newer, more expansive version of the LAPD’s points-based Chronic Offender formula than has previously been reported. Older reports have shown that analysts were supposed to count points against individuals for gang membership, being on parole or probation, prior arrests with a handgun, past violent crimes, and “quality” police contacts. This newer version from October 2017 includes most those checkboxes, but expands the gun penalty now counting up five points for “each incident” involving any kind of gun over the last two years. It also counts up five points for each violent crime arrest, whereas the older version just counted five points if an individual had violent crimes on their rap sheet.

The documents were obtained through a public records lawsuit, brought by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition in March, which sought information on a larger LAPD program in which the Chronic Offender Bulletins are used. Since 2011, that program, known as Operation LASER, has targeted Los Angeles neighborhoods with high densities of gun-related crimes, teaming up analysts and officers to target “chronic” offenders and areas. According to a 2017 LAPD grant extension request to the Department of Justice’s Smart Policing Initiative Grant Program, obtained by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, at the time, the department was targeting neighborhoods in South and Central Los Angeles, which are mostly Black and Latino, and planned to expand the operation to more police divisions across the city.

The LAPD has claimed success with the program — between 2011 and 2012, one area where LASER was operating experienced a 56 percent decrease in homicides (according to a 2014 report by the LAPD). But the report was unable to single out whether this was because of the use of Chronic Offender Bulletins or some other unrelated trend. Homicides in Los Angeles had dropped steadily since the early-nineties before leveling out around the middle of this decade.

But residents say these predictives tactics have come with a cost. “I feel like they already know who you are by the time they stop you or give you a citation. They already know your name and who you are hanging out with,” said one member of a focus group convened by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition for a new report it released today, alongside the public records.

Another focus group member elucidated the dangers of constantly focusing police resources on a very specific population: “Because they over-patrol certain areas. If you’re only looking on Crenshaw and you’re only pulling Black people over then it’s only gonna make it look like, you know, whoever you pulled over or whoever you searched or whoever you criminalized that’s gonna be where you found something,” said the participant.

Activists say these testimonies are only their first step in their push for reforms. On June 5, Los Angeles is having its first hearing on data-driven evidence-based policing, says Garcia, where her group plans to push presenters, many of them with deep ties to the LAPD, on what impact this type of profiling can have on their target communities. Garcia wonders, “Where are the hard questions going to come from if you are working with someone to present this information to the community who has every motivation to make the community agree with these programs? There’s a lot at stake.”