The Family Of An Unarmed High Schooler Shot By Police Begs For ‘Real Change’

The King County Sheriff’s Office told reporters Tommy Le had a knife. He was actually holding a pen.

For those who loved Tommy Le, the 12 months since he was killed by police on a suburban Seattle street have been what his aunt Uyen Le described last week as “a year of unending grief, shame, and humiliation.”

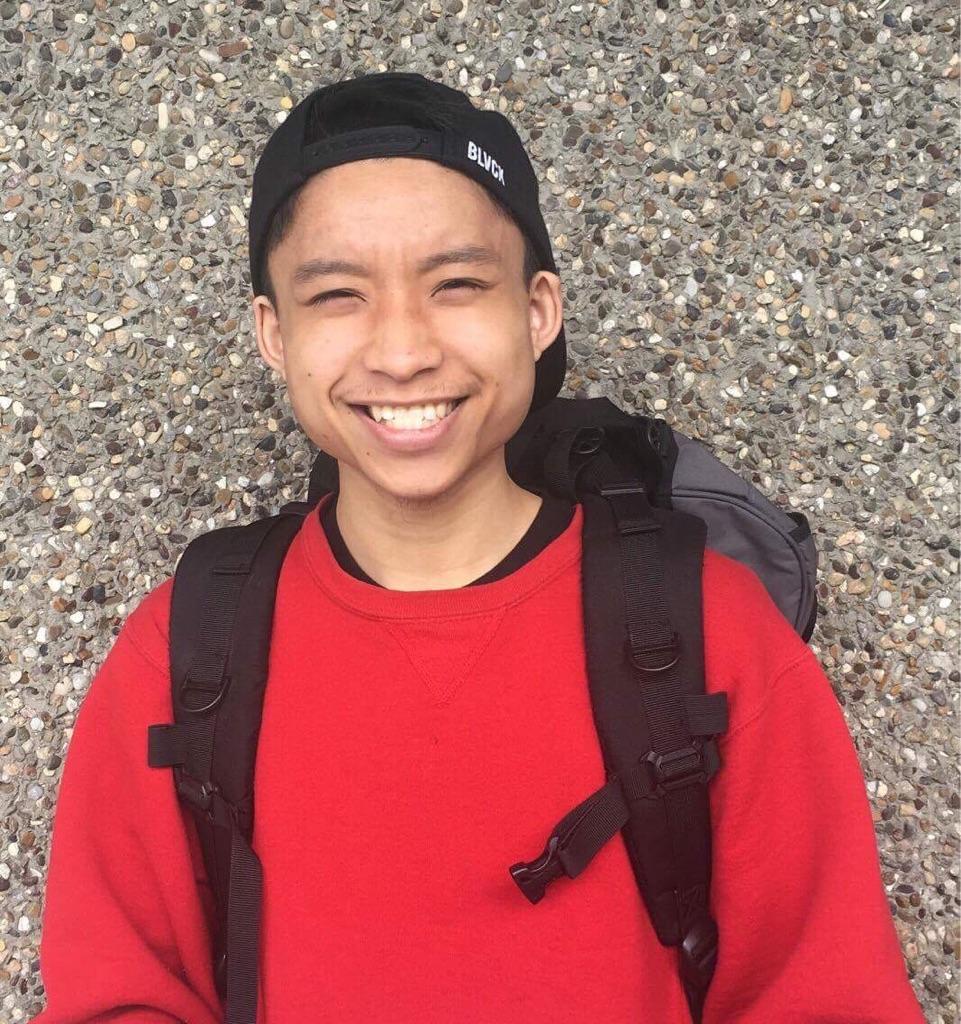

Le, the 20-year-old son of Vietnamese refugees, was hours away from graduating from high school when he was shot by a deputy sheriff on June 14, 2017. The young man’s family was heartbroken by his death, and Washington State’s large Vietnamese-American community shared a piece of their pain.

But Le’s family says their hurt was amplified by an allegation made by King County Sheriff’s Office officials hours after Le was killed. Officials with the sheriff’s office, which provides police services to many Seattle suburbs, released a statement indicating Le charged deputies with a knife. Nine days passed before the claim was corrected.

In fact, Le was carrying a black ink pen when he was shot, not a “knife or some sort of sharp object” described in a media release on the sheriff’s office Twitter feed. No knife was found.

Those statements were the subject of an independent review of the communications related to King County deputy-involved shootings. In a report released Tuesday, researchers with the University of Florida’s Brechner Center for Freedom of Information noted the sheriff’s office misinformed the public and then didn’t correct the record. Le’s family addressed King County leaders during a Seattle hearing on the report.

Responding to the Brechner Center findings, King County Council Chair Joe McDermott blamed the sheriff’s office for the untrue statements.

“Tommy’s aunt spoke about a year of grief, shame, and humiliation,” McDermott said during the Tuesday hearing. “It strikes me that Tommy’s death alone would cause the grief. But the shame and humiliation were caused and compounded by inaccurate information that was disclosed in the first place and then wasn’t corrected.”

The night he was killed, Le was walking near his home in Burien, a racially diverse, economically mixed city abutting Seattle’s southern city limit. According to law enforcement, deputies rushed to the area just after midnight when a resident reported firing a warning shot at a ranting man brandishing a knife. The sheriff’s office contends Le was identified to deputies as the unstable, armed man.

Three deputies confronted Le, who, at 5’4, was significantly smaller than the man who killed him, identified by the sheriff’s office as Deputy Cesar Molina. According to the office, Molina and another deputy fired Tasers at Le twice before Molina shot Le, who was then handcuffed as he lay dying. An autopsy by the county medical examiner would later show Le’s liver, left kidney, and spleen had been shredded by two hollow-point bullets.

In a statement to The Appeal on Friday, King County Sheriff Mitzi Johanknecht said her office may revisit its use-of-force policies once a review of Le’s shooting is complete. Johanknecht said she hopes the review will address questions the Le family has about Le’s death, while pledging to work on improving communication and transparency.

“No one wants to see a 911 call for assistance result in a death and I am saddened by the loss of any life,” said Johanknecht, who was elected to her first term as sheriff in November. “I am confident … the review processes in place will determine whether there is a need to revise the training or policies regarding the use of deadly force in unknown and potentially dangerous situations, such as this one.”

The initial sheriff’s office statement after the shooting asserted Le had a weapon in hand when he was shot.

“A homeowner fired a warning shot at a man running at him with a sharp object in his hand. When deputies responded to the scene, the suspect came at them as well,” last year’s statement reads.

Brechner Center researchers noted “the release did not specify Le’s weapon but stated that he was ‘holding a knife or some sort of sharp object.’ Much of the resulting press coverage seized on the idea that Le wielded a knife, and the Sheriff’s Office did not correct any of the inaccurate reports.”

Jeff Campiche, an attorney representing Le’s family in a civil lawsuit against King County, told The Appeal that the sheriff’s office “wanted to make themselves look better because they shot an unarmed, 120-pound high school student in the back.”

“Is it possible, after the young man is lying on the ground bleeding to death, that the sheriff’s office didn’t know he was unarmed?” Campiche asked.

Demanding Candor After Shootings

Johanknecht said her office “values transparency and the public’s trust.”

“It is not the policy of the KCSO to intentionally mislead the public, media or anyone regarding its interactions with the communities we serve,” she told The Appeal, referring to the King County Sheriff’s Office.

Despite heightened public interest in police violence, police practices vary widely when it comes to disclosure after officer-involved shootings.

As part of their review, Brechner Center researchers contrasted the Louisville Metro Police Department’s aggressive disclosure of reports related to police shootings with the Los Angeles Police Department’s approach, which they described as “reactive and restrictive.” Authors of the report, led by Brechner Center director Frank D. LoMonte, describe a national trend toward greater proactive disclosure and away from requiring the public to fight for access to information.

The new transparency is in part self-serving. Researchers noted that the Chicago Police Department compounded a public relations disaster after the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald by fighting the release of a dashcam video for more than a year. The apparent cover-up cost Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy his job, and the city paid millions of dollars to settle the McDonalds’ lawsuit. The officer who killed McDonald has since been charged with murder.

Deborah Jacobs, who was picked last year to head King County’s police oversight office after 13 years as executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s New Jersey chapter, said Tuesday that communities around the country are demanding candor.

“The initial information released by law enforcement shapes the narrative and becomes the public understanding of an incident,” Jacobs said. “The release and perpetuation of inaccurate or misleading information about an incident has serious potential consequences for all involved.”

Jacobs advocates for what she characterized as small but critical moves toward disclosure suggested in the Brechner Center report. One key change would require the sheriff’s office to regularly update the public on high-profile incidents, including officer-involved shootings, through press briefings and social media. The office would also be required to immediately correct inaccurate or misleading information it publicized.

Calls for Accountability

Le’s death helped prompt an expansive review of another piece of King County’s response to officer-involved killings: the shooting inquest.

Inquests are fact-finding trials in which jurors rule on the facts of a contentious incident without awarding damages or assigning a punishment. Prosecutors call witnesses and present evidence to the jury, which then judges the legality of the shooting.

“Their basic function is to figure out, as best they can, the truth about how someone died and to explain that truth to the public,” Paul MacMahon, an assistant professor of law at the London School of Economics who has written extensively on inquest systems, wrote in an email to The Appeal.

“That process can be itself a form of accountability for those guilty of wrongdoing. … Inquests can help institutions and the public to learn from mistakes, and to help victims’ families and society at large come to terms with difficult events,” he continued.

But advocates for police reform often find little to like about state inquest systems. King County’s inquest process, derived from a 164-year-old state law, provides no opportunity for the public to challenge the law enforcement account of a shooting. Le’s family has pushed for reform of this process, which their attorney calls a one-sided “whitewash.”

County Executive Dow Constantine paused all inquests in King County, including Le’s, in December and initiated a review he pledged will “make inquests more transparent, fair, and meaningful for all those involved, and to provide greater confidence in our justice system to the entire community.”

Inquests have proved useful in examining deaths at the hands of police elsewhere. A Milwaukee inquest jury faulted several officers involved in the 2011 death of Derek Williams, who died in the backseat of a squad car after police failed to provide him medical attention. Leaders in Clark County, Nevada, recently crafted an inquest system as part of a larger accountability effort.

A task force that includes a retired police leader and two people whose loved ones were killed by police recommended reforms to King County’s inquest system in March, but the county has yet to enact them. A representative for Constantine said the executive expects to issue an order in the near future. A sheriff’s office review board is expected to examine Le’s shooting in coming weeks.

So, as Le’s family members end their first year of grief, they wait.

“We’re begging for more,” Uyen Le, who was raised with her nephew, said during Tuesday’s hearing. “Real action. Real change. Accountability. Only then will our family receive the justice that we and Tommy deserve.

“We are a strong Vietnamese family, a good family, and we’re supported by the greater community. We will not give up until the county decides to take responsibility for what happened to Tommy.”