The Dissenter

Former Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Bernette Johnson’s fiery dissents on mass incarceration and sentencing in America’s most carceral state garnered international attention. But the rise of the first Black woman on the court was characterized by one battle after another with the Deep South’s white power structure.

It was late October, only a week after Fair Wayne Bryant walked out of Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Bryant’s freedom had not been preordained. The 63-year-old was more than two decades into a life sentence for breaking into a carport storeroom in Shreveport. Bryant’s arrest stemmed from a police search of a van he was riding in where hedge clippers were found. The owner of the home said that the hedge clippers belonged to him; Bryant denied taking them and Bryant’s cousin said they were his.

He had been intermittently incarcerated since he was a young man.

Bryant was previously convicted, and sentenced to 10 years in prison, for the 1979 attempted robbery of a cab driver during which an accomplice shot the driver. He was then convicted in 1987 for the theft of multiple telephones, a remote control, and “a robot” from RadioShack, and sentenced to two years of hard labor. In 1991, he was sentenced to 18 months of hard labor after forging a $150 check. Then, in 1992, he was sentenced to four years for another burglary.

The now-infamous life sentence, covered everywhere from the Guardian to CNN, was a result of Caddo Parish district attorneys invoking the state’s habitual offender statute—in August 1997 and again in February 2000.

For decades, Caddo was a snakepit of racism in which Black people were wrongfully prosecuted and frequently prevented from serving on juries at a courthouse that, until 2011, proudly displayed the flag of the Confederacy. Attorneys for Felton Dorsey, a Black man sentenced to death in Caddo Parish in 2009 for killing a white former firefighter, wrote in a brief that he suffered discrimination in his case because Black people were struck from his jury and “the quintessential symbol of white supremacy looms over the courthouse.”

As The Appeal chronicled in 2019, under the habitual offender statute, a district attorney “can file to have a person’s punishment enhanced based on their criminal history.” In practice, the freedom to inflict a disproportionate penalty meant that a person could be sentenced to 13 years in prison for possessing about three grams of marijuana, and another could face 20 years to life for stealing $31 worth of candy.

Such sentences were so flagrantly excessive that, in 2017, state lawmakers significantly lessened the punishments. These reforms, signed into law by Governor John Bel Edwards, didn’t benefit Bryant because his sentence was deemed legal at the time it was imposed.

And yet, here Bryant was, chatting via Zoom. He’s got a gleaming bald pate, a kink in his back, and some pain in his shoulder. He’s flummoxed by cellphones, having last used a push-button model.

Bryant was recalling where he learned of the dissent, written by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Bernette Johnson—the first and only Black woman to hold the position.

“I was in the dormitory, man, in penitentiary. An inmate counselor that was from my hometown, he got an email that morning.” Bryant was shocked, primarily because in July 2020 the Louisiana Supreme Court refused to review his sentence. “That was one writ that they shouldn’t have denied.”

“It is cruel and unusual to impose a sentence of life in prison at hard labor for the criminal behavior which is most often caused by poverty or addiction,” the counselor read to Bryant. In her July 31 dissent, Johnson had noted with withering precision that laws like the habitual offender statute were the “modern manifestation” of post-Reconstruction era “pig laws,” which allowed Southern states to enslave Black Americans without running afoul of the 13th Amendment. “Pig laws,” Johnson wrote, “targeted actions such as stealing cattle and swine—considered stereotypical ‘Negro’ behavior—by lowering the threshold for what constituted a crime and increasing the severity of its punishment.”

In her dissent, Johnson also blasted the profound moral and fiscal costs of mass incarceration. “Since his conviction in 1997, Mr. Bryant’s incarceration has cost Louisiana taxpayers approximately $518,667,” Johnson wrote, “Arrested at 38, Mr. Bryant has already spent nearly 23 years in prison and is now over 60 years old. If he lives another 20 years, Louisiana taxpayers will have paid almost $1 million to punish Mr. Bryant for his failed effort to steal a set of hedge clippers.”

“This man’s life sentence for a failed attempt to steal a set of three hedge clippers is grossly out of proportion to the crime and serves no legitimate penal purpose,” she concluded. “For the reasons cited, I would grant the defendant’s writ application.”

The significance of this rifle-shot dissent was not immediately clear to Bryant. He understood, though, that he had an ally on the state’s highest court. But he could see that, despite her seniority, the chief justice was but one voice—that of a Black woman on a court otherwise white and male. “I understand everything that she went through, trying to help me,” Bryant says, his voice filled with unnerving equanimity. “But sometimes, you ain’t going to be successful in everything you set out to do in life. You’re going to always have someone somewhere fighting against you.”

This is particularly true, not just in Louisiana but in state supreme courts across the country. In Florida, the all-white Supreme Court bolstered executions amid a pandemic. And in a 4-3 vote, Michigan’s court—which has since flipped to Democrats—hamstrung Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

“State supreme courts matter because they are the primary interpreters of state law. In the U.S., we have both federal law and state law, and the federal courts will defer to the interpretation of a state law by its own state supreme court,” Loyola University New Orleans law professor Andrea Armstrong told The Appeal. The state supreme courts are also important because, in criminal cases, they generally handle the appeal. “That may be the first time that someone is looking at whether the punishment is excessive, for example, as compared to other cases.”

Johnson, 77, retired at the end of last year. She was often a sole voice arguing for justice. It was a lonely position, for which she fought ferociously. That the chief’s enemies, on and off the court, had for decades been so intent on limiting her influence—even colluding to prevent her from assuming the position of chief justice—made her accomplishments all the more impressive.

Over the last four months, The Appeal talked to dozens of people from Johnson’s life, including friends, classmates, judges, and former clerks. She did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

Inequality and Disparities

Bernette Joshua was born on June 17, 1943, in Donaldsonville, Louisiana, a farming community northwest of New Orleans. Her mother and Navy man father and three brothers lived under the segregationist yoke of Jim Crow.

From the beginning, Joshua’s intelligence and willingness to do the work was apparent. “Bernette was really smart,” said Cynthia Spears-Hills, a classmate at Walter L. Cohen High School in New Orleans, named for a free Black man who held office under presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Spears-Hills rued that she herself had not been sufficiently academics-minded to take courses with the future jurist—the class of 1960’s valedictorian.

Joshua’s first choice for college was Columbia University, but it didn’t admit women. Instead, she took a full scholarship to Spelman College, the famed historically Black women’s college in Atlanta. The Greensboro sit-in—a nonviolent protest against a segregated lunch counter in the North Carolina city, organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—occurred earlier that year, and it captured the students’ imagination.

“You have taken up the deep groans of the century,” Martin Luther King Jr. said in an address at Spelman that April. “The students have taken the passionate longings of the ages and filtered them in their own souls and fashioned a creative protest.”

Even professors were encouraging; Howard Zinn, chairperson of the college’s history and social sciences department, lent students his car to get to a demonstration. Lois Moreland, a beloved political scientist, provided counsel. “I was not a strategist for the movement, but I was supportive in the sense that anybody who is under pressure wants a sympathetic sounding board,” she recalled in an oral history.

Parents were terrified that their children would take part in off-campus demonstrations, with the murder a few years earlier of Emmett Till still fresh and the Ku Klux Klan, clad in burgundy robes, picketing in downtown Atlanta. (The yearbook editors made light of the terrorist organization, captioning a photo of Spelman women sitting with a classmate clad in a white hoodie, “They are celebrating Barbara’s great achievement—she is now a member of the Ku Klux Klan.”) So, for the most part, the students remained on campus, where they met up with men from Morehouse College for an hour or so a week, enjoyed co-ed bowling, or attended “sweetheart dances” at which they were serenaded. Every Sunday was vespers, and then lectures from the likes of civil rights leaders Julian Bond and Howard Thurman.

Spelman students were aware of how their parents scraped to send them to college. They knew their primary purpose was to study. But it was impossible not to engage in civil rights struggles. Leronia Josey, a classmate of Joshua’s, told The Appeal, “The inequity and the disparities and stuff were enough to drive you nuts, you know?” Josey, who became a lawyer, remembered her father sending the administration a letter, begging to keep his daughter away from protests.

Joshua, who wrote for the student newspaper and headed the school’s NAACP chapter, was a class standout. But she was hardly alone. There was Marcelite Jordan, who became the first Black female general officer of the United States Air Force; Alice Walker, author of “The Color Purple”; and Ida Rose McCree, a firebrand activist who was photographed holding a sign that read “WE WANT TO SIT DOWN LIKE ANYONE ELSE” as King, to her right, was led away by Atlanta police.

For Joshua and her fellow political science majors, the law was seen as a potential instrument of justice and equality. During those years of protests and “mass meetings” at Spelman, and Saturdays picketing a local department store, she became acquainted with attorneys. The summer after graduation, she worked for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund on desegregation cases in the South. Joshua saw that, while Brown v. Board of Education was a judicial landmark, enforcement required filing dozens of lawsuits across Louisiana—an experience that convinced her to go to law school. “I had a chance to see these civil rights lawyers at work,” she later told Louisiana Bar Journal, “and I decided that this was a way to be a change agent.”

Louisiana State University had admitted Black students to its law school once before. In 1951, Pierre Charles, Robert Collins, and Ernest “Dutch” Morial began their studies. Charles dropped out after one semester, but Collins and Morial graduated in 1954. “Generally there was not a great deal of hostility,” Morial would say, but there were, he allowed, “some who shunned myself and Collins.”

It was another decade before LSU law school—whose dean, Paul Hebert, had been a Nuremberg trial judge—admitted more Black students. In September 1965, Joshua and Gammiel Gray (now Poindexter) began their studies. Gray, a future General District Court judge in Virginia, had wanted to be a lawyer since she was 7 years old in Baton Rouge. She didn’t want to do civil rights cases in particular (although eventually, she would); she had a generalist, storefront vision of criminal and civil law, focused on solving problems specifically for Black clients.

Classes were divided into two sections, and the university intentionally grouped the women together. Joshua and Gray had only each other on campus, and they held their own. More than a third of the aspiring lawyers dropped out by the end of the first year, and less than half of the initial class of students managed to graduate.

On a campus where future Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke would soon roam the grounds, the pair faced constant discrimination. A contract law professor had difficulty looking Gray in the face. “It was clear,” she told The Appeal, “he could not stand me being there.” Classmates were often no better and refused to sit next to them. Not long after several legal challenges to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there was a class discussion of the interstate Commerce Clause being used by Congress to impose integration of public facilities in the South. A professor said legislation was justified because Black Americans couldn’t find public restrooms and restaurants during travel. According to Poindexter, a male student shouted, “Well, they goin’ on a trip. Why can’t they make their own bologna sandwiches and carry it with them? And fry their own chicken and carry it with them? Why do I have to give up some of my rights?”

Often, classmate Charles Weems told The Appeal, the white law students made their opinions of Black people known by hanging Confederate flags in the back windows of their vehicles.

Benjamin Shieber, their constitutional law professor, was an exception. He treated the women with respect, and when Gray’s father died her senior year, he attended the wake. Shieber, 92, remembers when Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. He wore a black tie to quietly mark the occasion. “Most of the students in the law school were, I’m sorry to say, racist at that time,” he said. “They were not at all unhappy about the fact that Martin Luther King had been assassinated.”

The summer before their second year, Joshua and Gray got jobs organizing in southwest Louisiana—in Opelousas, Lafayette, and Lake Charles. The area was home to an often violent white population, strongly against integration more than a decade after Brown v. Board. Joshua and Gray immersed themselves in the communities and spoke at rallies. They aimed to recruit young people for “freedom of choice” schools. Gray got a sense of Joshua’s worldliness, and her knowledge of oppression, abroad and at home. She talked about South Africa and apartheid. Or how Louisiana department stores were being forced to finally hire Black people. “These bougie middle-class Black people wouldn’t stay out of the stores when they were being boycotted. And then, when the jobs opened up, their children are the first ones who think they ought to have [them],” Joshua told Gray with some disdain.

The next summer, the pair went to Washington, D.C., where Joshua worked for the Justice Department and Gray for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The months they were roommates were glorious for Gray. She’d never met so many people, and loved the city and its freedom. She made up her mind to return after law school.

Later, however, when the women were planning their next steps, Gray asked Joshua about moving to Washington. “Gammiel, we’ve done that,” Joshua replied. “That’s what you do when you’re 22. Now we need to go back home and start our work.”

The Work Begins

Joshua returned home to Louisiana. In 1969, she became the managing attorney at the New Orleans Legal Assistance Corporation. As recounted in the Times-Picayune, she focused on consumer protection in the Lower Ninth Ward, a majority Black, working-class neighborhood. Salespeople frequently saddled the neighborhood’s homeowners with onerous interest rates. “You had folk who owned this little house, they owned this little piece of land,” she told the paper in 2019. “Someone passes by one day, knocks on the door and asks, ‘Wouldn’t it really look nice if you put some aluminum siding up?’ Then, all of a sudden, you miss a payment and there is a horrendous interest rate and now you’ve lost your house.”

For four years, starting in 1974, Joshua was assigned to cases in federal and state district courts, as well as in juvenile court. She married Paul Johnson, with whom she would have three children: Mark, David, and Rachael, a future judge.

In 1981, Johnson became New Orleans deputy city attorney for Ernest Morial, the city’s first Black mayor and a fellow LSU grad. In addition to overseeing a largely Black cadre of younger attorneys, Johnson represented the city in cases ranging from private property disputes to police brutality. Notably, she worked on litigation stemming from the police strike of 1979, which was staunchly opposed by Morial and led to a historic cancellation of Mardi Gras parades.

Johnson was exhaustively prepared and intensely focused. When asked about his first impressions of her, Michael Bagneris, Morial’s then-executive counsel, hesitated a bit then said: “She didn’t take any shit from you.”

The job of deputy city attorney was not generally a stepping stone, but for Johnson it was. She left the mayor’s office after a few years, and in June 1984 announced a run for a seat on the Orleans Parish Civil District Court.

The next month, Johnson’s 13-year-old son Mark died of heat stroke during a high school football practice. He was, she told a reporter, a healthy and active kid. As a newspaper account described it, the coach “forced their son Mark to keep running in the heat and humidity even after he complained of feeling ill” and deprived the players of breaks. According to reports, the Johnsons sued the coach and the school for $516,000.

As a Black person, you never think you’ll get justice at any judicial level, state or federal. You always had all-white everything: white judges, white this, white that, white police officers. To get any judicial help at a state level, you needed somebody who at least looked like you.

Ronald Chisom New Orleans activist

At the outset of 1985, Bernette Johnson, 41, became Judge Johnson. She was the first woman elected to the Orleans Parish Civil District Court.

It was a monumental moment. The history of Black lawyers and Black judges in Louisiana is rife with racism and suppression. Jim Crow kept the legal profession all-white. It wasn’t until 1950 that Southern University—like Spelman, an HBCU—graduated its first law school class. It wasn’t until 1978 that Orleans Parish Civil District Court had a Black judge, when Revius Ortique Jr. was appointed by the Louisiana Supreme Court. And while there had been a smattering of Black judges across the state, there had never been a Black justice on its Supreme Court, which was established in 1813. This was true in the years after Reconstruction, when Black Americans began to migrate to New Orleans, and it was true a century later, when they comprised more than half the city’s population.

Indeed, that was by design.

The state’s Supreme Court was kept all-white by making it as difficult as possible for Black Louisianans to vote. In 1898, undermining the 14th and 15th Amendments, state lawmakers instituted, among other measures, literacy tests and property requirements. Voting registration among Black Louisianans plummeted. “Even once the Voting Rights Act [of 1965] began opening up voting rights in registration and in legislative races, there was a presumption that the judiciary was ‘above politics,’ so the VRA would not, and could not, apply to judicial races,” William Quigley, professor of law and director of the Loyola University Law Clinic, told The Appeal.

Exacerbating the civil rights crisis, the lines for the Supreme Court seat were redrawn in 1974, as New Orleans was becoming a majority-Black city.

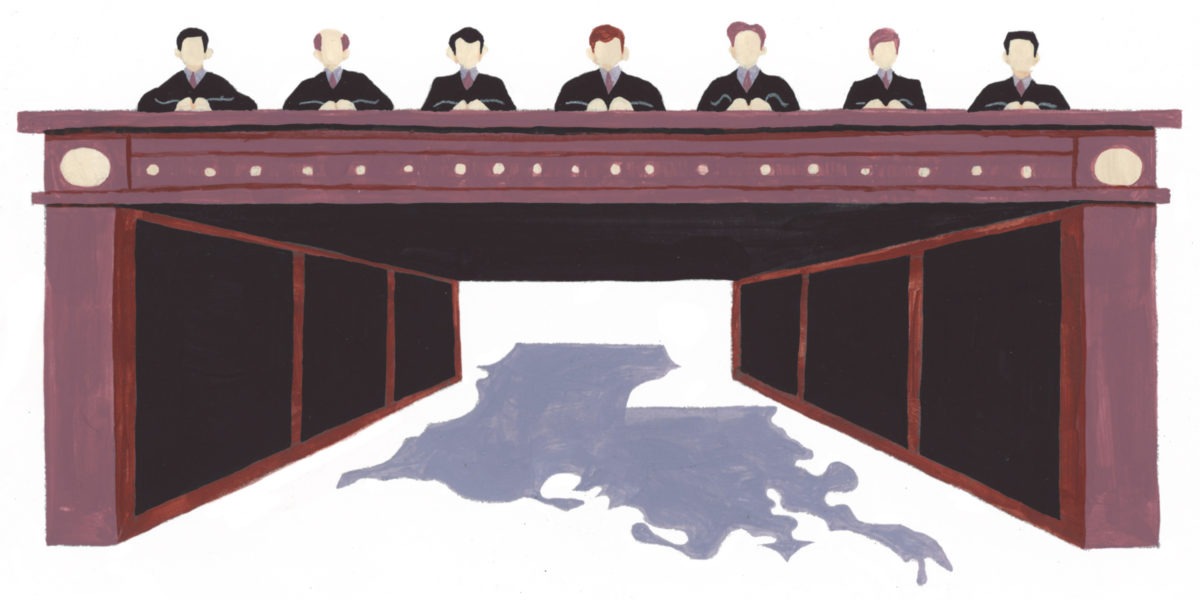

There were a constitutionally mandated seven justices on the Louisiana Supreme Court, elected from six geographical judicial districts. All but one of the districts elected one justice apiece. The First District—comprising Orleans, Plaquemines, Jefferson, and St. Bernard parishes—elected two. By the late 1980s, the population of Orleans Parish was majority-Black, but the population of the four parishes combined was 63 percent white.

This made it nearly impossible for residents of New Orleans, then the most populous city in the state, to elect a Black justice to the Supreme Court.

Enter Ronald Chisom, a renowned local activist who took on slumlords. Chisom was tired of decisions regarding his humanity being made entirely by white people. “As a Black person, you never think you’ll get justice at any judicial level, state or federal. You always had all-white everything: white judges, white this, white that, white police officers,” Chisom, 79, told The Appeal. “To get any judicial help at a state level, you needed somebody who at least looked like you.”

On Sept. 19, 1986, as Johnson was nearly midway through her first term on the civil district court, Chisom became the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the First District. He and the other plaintiffs—including New Orleans lawyers Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, and Ernest Morial’s son, Marc—sued Governor Charles “Buddy” Roemer.

Chisom’s legal team, comprising Quigley, local attorneys, and legal giants Pamela Karlan and Lani Guinier, argued that Louisiana’s election system violated not only the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the 14th and 15th Amendments, but 42 U.S. Code § 1983, which prohibits the deprivation of individual civil rights as well. The lawyers argued that the state’s First District should be cleaved into two districts: Orleans Parish would elect one justice, while St. Bernard, Jefferson, and Plaquemine parishes combined would elect the other. That way, the vote of New Orleans residents would finally carry a weight equal to that of residents in the other, whiter parishes.

Chisom’s lawyers also sought class certification of the approximately 135,000 registered Black voters of Orleans Parish and, at minimum, a temporary halt to Supreme Court elections until the legal proceedings were over.

U.S. District Judge Charles Schwartz Jr. wasn’t persuaded—he said that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act did not apply to the election of state judges—and granted Louisiana’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Chisom’s legal team persisted, and less than a year later, the lawsuit progressed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. One judge, Samuel D. Johnson, argued that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act did apply to state judicial elections. Judge Johnson reversed the decision, and the court battles continued for several years until, in 1991, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Chisom.

“No one was certain we would win,” said Quigley. “All of us were certain justice was on our side.”

As a consequence of the decision and a federal consent decree, the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus had to create a compromise. It was a delicate situation. Two justices, Pascal Calogero and Walter Marcus Jr., were already representing Orleans Parish. If the lines were redrawn, one would likely lose a seat in an election.

The settlement, reached in 1992, was called Act 512. The plan was for the number of justices on the Supreme Court to temporarily increase to eight, and sit in panels of seven, similar to an appellate court. (Supreme courts have the power to assign any judge to their benches, an action most commonly used if there’s a recusal.) The temporary eighth justice, known as the “Chisom seat,” would be picked from the court of appeals and be from New Orleans. According to the consent decree, that justice would “participate and share equally in the cases, duties, and powers of the Louisiana Supreme Court” and “share equally in all other duties and powers of the Supreme Court, including, but not limited to, those powers set forth by the Louisiana Constitution.” Once Calogero and Marcus retired, the seat would automatically get redrawn and the Supreme Court would shrink back to seven. The settlement was to remain in effect until 2000.

As a direct result of the compromise, Revius Ortique, a lifelong New Orleanian who served in World War II, earned his law degree from Southern University in 1956, and litigated civil rights cases, was elected that year to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal. He became the state’s first Black Supreme Court justice.

Perschall v Louisiana

There’s little in the newspapers about Johnson’s early years on the Orleans Parish Civil District Court, to which she was re-elected in 1990. There are, however, scattered news items that give a window into her decisions.

In November 1987, Johnson ruled that Fair Grounds Race Course couldn’t require its jockeys to sign waivers absolving the track of liability. In September 1990, when New Orleans teachers went on strike, she declined to force the school system to hire certified substitutes, on the grounds that such an act was “beyond the authority of this court.” Three years into her second term, in December 1993, she ruled that the New Orleans Police Department was negligent for failing to discipline an officer accused of brutality.

Marc Morial tried several cases before Johnson. “She was a no-nonsense judge,” he said, “very studied in the law, not suffering clowning and foolishness in the courtroom.” Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux, the chief judge of the Third Circuit Court of Appeal, said Johnson was known for having “an empathy for those who came before her, because she had walked in their shoes.”

In 1994, two Supreme Court seats opened up because of the retirements of Ortique and a white justice named Pike Hall Jr. Johnson, who had recently been elected chief judge of the district court, announced a run for the Fourth Circuit—which, under the Chisom compromise, meant a seat on the Supreme Court. She had run for the seat two years earlier and lost to Miriam Waltzer.

Also running for the Orleans Parish seat was Waltzer, who is white and Jewish, and Fourth Circuit judge Charles Jones, who is Black. Both Johnson and Jones were publicly opposed to Waltzer being in the race. “If someone agrees with civil rights and has all their life, then they need to be with us,” Johnson told reporters. “And if someone says they agree with us on civil rights, but they’re opposed to us [being a Supreme Court justice], then their whole life has been a lie.” Jones, too, was blunt: “The race is about race.”

Waltzer denied that she was standing in anyone’s way, and suggested voters could elect whomever they liked: “Now that the playing field is leveled, I think I can play on it just like anybody else.”

Waltzer won 49 percent of the primary vote to Johnson’s 42 percent, while the rest went for Jones. Nonetheless, a week later, out of the belief that a runoff would be corrosive for the city—and because, she told The Appeal recently, threats of violence were made toward her family—Waltzer withdrew.

Five weeks later, in November 1994, Johnson was sworn in as associate justice by Mayor Marc Morial—whose father she worked for so many years earlier.

The attacks on Johnson’s legitimacy as a justice began almost immediately. Clement Perschall Jr., a white attorney from Metairie—a New Orleans suburb once home to David Duke and, more recently, the office of U.S. Representative Steve Scalise—filed a suit in district court, asserting that the legislation that created the temporary eighth seat was unconstitutional. He believed that, as a lawyer, he was therefore “unable to provide predictable legal advice to his clientele.” Perschall, asked the court to strike down the law and void every Supreme Court decision rendered since the Chisom settlement took effect.

With Perschall’s lawsuit bouncing around the courts, Johnson focused on the work. She found the Supreme Court vastly different from the district court, where she could “sign my name and make something happen.” Now Johnson had to convince three or more colleagues to take her side.

In November 1996, five justices agreed to bypass the lower courts and hear Perschall’s challenge to the Chisom seat, with oral arguments to begin the next year. That same month, she and Chief Justice Calogero implored their colleagues to overturn the death sentence of Albert Lavalais III—a Black man who at age 19 murdered a woman at the behest of her white husband, George Smith. Smith was sentenced to life in prison for ordering the murder. Johnson, in her dissent, detailed the historical resonance of Lavalais’s situation—he was a farmhand whose family had for years worked on Smith’s thousands of acres—and rebuked the prosecutor for saying Lavalais was an example of “plantation culture”:

“As can be expected with any ‘plantation culture’, after living on the land for several generations, individuals become economically dependent, and can easily be intimidated into carrying out the wishes of landowners, even when doing so is not in their own best interest. Such individuals become bound by emotional ties which are not easily untangled. Because of these circumstances underlying Lavalais’ actions and the nature of his relationship to Smith, Lavalais was under the domination and control of Smith, and such fact should have been a mitigating factor during the sentencing phase of Lavalais’ trial.”

Angela Smith’s body was never found. Lavalais’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison.

No one was certain we would win. All of us were certain justice was on our side.

Bill Quigley Professor of law and director of the Loyola University Law Clinic

“8TH SUPREME COURT SEAT IN JEOPARDY,” blared a Shreveport newspaper in February 1997, when Johnson, as well as justices Marcus and Calogero—whose seats were being questioned—recused themselves during a hearing at which Perschall asked the court to invalidate the agreement that brought Johnson to the bench.

Perschall, once again, argued that the seat was unconstitutional. The state’s lawyers argued conversely. Furthermore, they said, because state law and the federal court settlement were indistinguishable, the Louisiana Supreme Court was in no position to determine constitutionality. “You are being asked to do the unthinkable—having Louisiana law invalidate federal law,” said an attorney for the state.

With the lawsuit still pending in federal court, the Supreme Court ruled in July 1997 that the Chisom settlement had, in fact, violated the state’s constitution. However, because the seat had been created by the legislature, the court felt it couldn’t undo it. Thus, the seat would remain. Morial was furious. “This opinion sends a very disturbing signal to the nation about Louisiana,” he said. “What this does is create the prospect that compromise is replaced with conflict.”

In December, Charles Schwartz, the federal judge who years earlier had been unpersuaded by the Chisom lawsuit itself, upheld the creation of the seat.

James Williams, an ambitious attorney who once collaborated with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas on a law journal publication, became Johnson’s clerk not long after the Perschall decision. If she was angry or resentful that her colleagues ruled the seat she occupied was unconstitutional, Johnson didn’t let it show. But, he said, “it was certainly a frustrating feeling.”

In January 1998, in her capacity as chairperson of the National Bar Association’s Judicial Council, the country’s largest organization of Black judges, Johnson invited Thomas to speak at the summer’s annual convention. The group’s members were furious and moved to rescind the invitation. The contretemps thrust the organization into the national spotlight. Johnson was unmoved by the dissension. “The British are sitting down with the Irish. Palestinians are talking with Jews. And the Hutus can make peace with the Tutsis. But we can’t live with Clarence Thomas,” she said.

Johnson didn’t mind angering colleagues, whether from the Judicial Council or on the bench. “She pisses them off quite often,” Alanah Odoms, head of the ACLU of Louisiana, said recently. By the late 1990s, taking a humane position on the inequities of the criminal legal system put Johnson decidedly out of step with Louisiana. Williams said the disproportionately negative effect on Black people in the state “kept her up at night.”

Johnson wasn’t a traditional liberal (her jurisprudence was arguably to the right of, say, Miriam Waltzer’s), but her opinions could seem progressive. This is particularly true on a court that had only become more conservative. Morial said that, historically, Louisiana’s Supreme Court was progressive for a Southern state, and remained so at least through the 1970s and 1980s. But then the state at large went from purple to red, and the court went with it. That was “a frustration to Justice Johnson.”

Black people in Louisiana had few allies on the court. Consider the case of Dobie Gillis Williams, convicted of murder in 1984 and sentenced to die. His lawyers argued that, in the event of a stay, Williams deserved a new execution date. The Supreme Court, with the exception of Johnson, disagreed, and Williams—famously championed by Sister Helen Prejean—was executed by lethal injection in 1999. That December, Johnson was, again, the lone dissenter when the court restored the life sentence of James Tyrone Randall, convicted of simple robbery, of a bicycle, and previously for possession of stolen goods; the sentence, applied under the habitual offender laws, had been vacated by an appeals court. Then, in 2001, Johnson was alone in arguing that Emmett Dion Taylor, a Black man accused of murdering an elderly pharmacist, should be granted an appeal. His lawyers believed that prosecutors intentionally kept Black people off the jury.

That same year, in a widely publicized case, the Supreme Court upheld Timothy Jackson’s sentence of life without the possibility of parole for shoplifting a $160 jacket. Jackson, a New Orleanian with a sixth-grade education, struggled with substance use disorder. Instead of giving him the standard two-year sentence, the court—taking into account a conviction in juvenile court and two car burglaries—decided he should spend the rest of his life incarcerated. After Louisiana’s Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals decreased the sentence, the Supreme Court majority ruled, as the ACLU put it, “that judges may not depart from life sentences mandated by the habitual offender law except in rare instances.” Johnson wrote, “This sentence is constitutionally excessive in that it is grossly out of proportion to the seriousness of the offense.”

By then, Johnson was in her second term as associate justice. She had finally been elected to the Supreme Court itself, and the Chisom seat vanished.

The most pivotal moment in Johnson’s career on the court was arguably one entirely out of her control. On the morning of Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010, Chief Justice Catherine “Kitty” Kimball awoke to find that she could not walk in a straight line. “Honey, I’m having a stroke,” she said to her husband. Almost precisely a year prior, she had been sworn in as chief—a position given to the member of the court with seniority. Kimball, the first woman elected to the court, succeeded Calogero.

Kimball was released from the hospital in Baton Rouge in February 2010, after surgeons removed a clot in her brain. But within months, Kimball told reporters she couldn’t see out of her right eye, had not resumed her administrative or judicial duties, and was participating in Tuesday conferences from home. She planned to return to the court at the end of the year. But in April 2012, six years before the end of her term, and two years and two months after the stroke, Kimball announced her retirement—effective Jan. 31, 2013.

Kimball had returned to the court, but only briefly and not at anywhere near full capacity. Johnson picked up the slack in her absence.

The Battle for Chief

By the summer of 2012, two justices were vying to be chief: Johnson and Jeffrey Victory, who was sworn in to the Supreme Court a month and a half after Johnson was sworn into the Fourth Circuit. The Louisiana constitution was clear: “The judge oldest in point of service on the supreme court shall be chief justice.” Victory, a social conservative, had argued for more than a decade that he should have seniority, but because a vote on the next chief was far in the future, he hadn’t made an issue of it. On June 12, Johnson informed her colleagues that a “transition team” would begin working on her succession. Victory, however, believed Johnson’s time on the Fourth Circuit effectively didn’t count, and within hours of Johnson’s announcement, he and the other justices reportedly met to discuss an alternative. (“I have no knowledge of any such meeting, and if it did occur, I was not present,” former justice Greg Guidry, now a federal judge appointed by President Donald Trump to the Eastern District of Louisiana, told The Appeal.) Kimball, according to Johnson, offered a compromise: Johnson would take over as chief in 2017, after Victory and Jeannette Knoll, who took office in 1997. Johnson rejected the offer. The day after the transition announcement, Kimball wrote a memo to the justices, soliciting their opinions on seniority.

The memo was framed as a matter of personal belief (“Any sitting Justice interested in a legal determination of this matter may file with the Clerk of Court…”), when it was, in practice, an end run around Chisom.

Johnson hired James Williams and filed a lawsuit in federal court to stop the process. She argued the constitutionality of her seniority had been settled since 1992, so it wasn’t up for debate. The next day, three federal judges recused themselves from the case, and it was transferred to district court. The Justice Department’s civil rights division, which had been asked by Black lawmakers to intervene, supported Johnson, pointing to the Chisom settlement.

On July 25, Johnson addressed the state Senate Judiciary Committee. She told its members that, in nearly a year as acting chief justice following Kimball’s stroke, “I was never challenged by any other justice or staff as to my authority as acting judge.” To demonstrate that Johnson had indeed been a justice longer than Victory, Williams showed the committee a photograph taken early in Johnson’s first term. The group shot of the court’s eight justices had arrived in the mail, sent anonymously. Johnson was in the photo; Victory was not.

The next month, Governor Bobby Jindal entered the fray. In a motion filed with the district court, his executive counsel said the decision over who would succeed Kimball as chief should be left to the state.

That the lawsuit was necessary at all was because of “a racially motivated effort to bar a Black woman from occupying this key role on the state’s highest court,” Kristen Clarke, president of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, told The Appeal. (Clarke was recently nominated as assistant attorney general for civil rights in the Biden administration.) In July 2012, Johnson’s lawyers, including Clarke, filed a motion in federal court to affirm her qualifications to serve as the chief justice of the Supreme Court.

A racially motivated effort to bar a Black woman from occupying this key role on the state’s highest court.

Kristen Clarke President, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

On Aug. 16, 2012, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, arguments began in Chisom v. Jindal. Among the defendants were Kimball, Victory, Knoll, as well as associate justices Guidry, Marcus Clark, and John Weimer—who, it was alleged, colluded to prevent Johnson from being chief. (Attempts to reach Kimball, Victory, Knoll, Clark, and Weimer for this story were unsuccessful.) There was an overflow crowd in Judge Susie Morgan’s courtroom, with Black judges from around the state sitting in the jury box. As the lawyers saw it, this was another chapter in the landmark Chisom case, and Ronald Chisom himself was in the crowd. In a courtroom down the hall was another group of attendees, most of whom wore black buttons emblazoned with ‘BJJ’ and ‘CHISOM’ in white type.

The arguments were largely a retread of the Perschall case: Was the Chisom seat the constitutional equal of the other Supreme Court seats? If it was, Johnson had seniority and deserved to be chief. “In 200 years, every chief justice has ascended to the position by ascending automatically,” Williams told the court. Williams said that, because of the consent decree, Johnson was the equal of her fellow justices from the moment she was elected to the Fourth Circuit. To emphasize Johnson’s seniority, Williams again produced the group photo of the justices. “Obviously, Justice Victory is noticeably absent.”

The lawyer for the state argued that it wasn’t taking a position on who should be chief. “No one has suggested that Justice Johnson should not be the next chief justice,” he said, disingenuously, and the matter should be left up to the state Supreme Court to decide.

After the hearing, Chisom stood in the courthouse plaza. “To put it under the state—I’m nervous about that,” he said, according to The Associated Press. “I’m frightened about that.”

Chisom’s fear wasn’t borne out. On Sept. 1, Judge Morgan sided with Johnson. “The Court finds that the Consent Judgment provides for Justice Johnson’s service on the Louisiana Supreme Court … from November 16, 1994, to October 7, 2000, to be credited to her tenure on the court for all purposes under Louisiana law,” she wrote.

Jindal’s lawyer asked the Fifth Circuit to review the ruling, but the state dropped its appeal and the Supreme Court, with Johnson, Knoll, and Victory recused, voted unanimously to make Johnson chief.

“In my opinion, the justices listened to the wisdom of the public,” said Quigley, the law professor who was on Chisom’s legal team. “They lost big in court, and lost even bigger in the court of public opinion. They are smart lawyers who made a grave mistake. They realized their mistake and cut their losses.”

On a cold New Orleans day, Feb. 28, 2013, hundreds of people crowded in front of the Supreme Court in the French Quarter. Watching a Black woman take the oath of office as the most powerful jurist in the state was, for many in attendance, an overwhelming experience. It was also a resounding defeat for Jindal, who was in his second term as governor and was considered one of the most promising figures in the Republican Party.

The Chief Dissents

In the late 1990s, after Perschall, there was an incident that James Williams remembers with clarity. Johnson had a meeting with her three clerks. “Look, our opinions are not going to convince anybody of our position” she told them. “So instead of watering down our position to try to get votes that we’ll never get, we’re better off with strong dissents.”

Dissents aren’t a consolation prize for the losing side of a decision; they are both an insight into intracourt conversations, and a hint of the law’s possibilities—a signal to lawyers where a judge’s votes would lay. As society changes, values and laws change with it. In November, the U.S. Supreme Court denied the appeal by prisoners in a Texas geriatric prison, who asked that a lower court’s order mandating that COVID-19 safety protocols be followed. In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor bluntly described the consequences of her conservative colleagues’ actions: “If the prison fails to enforce social distancing and mask wearing, perform regular testing, and take other essential steps, the inmates can do nothing but wait for the virus to take its toll.” More recently, when Sotomayor broke with the majority in the decision to allow the federal execution of Dustin John Higgs to proceed, she blasted the Department of Justice’s string of government-sanctioned killings in 2020 and 2021. “To put [this moment] in historical context, the Federal Government will have executed more than three times as many people in the last six months than it had in the previous six decades,” she wrote, concluding: “This is not justice. … I dissent.”

A century ago, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan was known as “the Great Dissenter,” most famously breaking with his colleagues on Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 decision that established the “separate but equal” doctrine. The Plessy ruling was a “bible,” said Justice Thurgood Marshall, himself known for contributions to the law through dissents. Marshall used them to argue for affirmative action, in favor of true desegregation, and, repeatedly, against the death penalty. Marshall would ask his clerks, Loyola University’s Armstrong told The Appeal, “So, how do you feel about writing dissents?”

“It’s not just vanity that makes a judge or justice take time to write a dissent,” said Armstrong. “It is their contribution to a vision of what the law does.” It was as chief justice that Johnson truly cemented her legacy—which, to a great degree, is found in her dissents.

On March 12, 2019, John Esteen collapsed in front of the parole board. Decades earlier, the Gulf War veteran had been convicted of multiple offenses, including those involving cocaine and racketeering. Like Fair Wayne Bryant, Esteen had been sentenced under habitual offender laws. His punishment, 150 years, was effectively a death sentence.

With hindsight, one can draw a line between a pair of Johnson dissents and a second chance for Esteen.

In 2007, Wesley Dick was serving a life sentence of hard labor without the possibility of parole on a 2000 conviction for heroin distribution. Dick had been incarcerated for eight years and was attempting to have his sentence reduced. Dick had reason to believe this was possible; in 2001, the Louisiana state legislature passed reforms that included the elimination of life without the possibility of parole sentences for distribution of heroin.

The court ruled, however, that such reforms could not be applied retroactively. Johnson, then an associate justice, energetically dissented. She cited the 2001 reforms, and argued their intent was “clear and unambiguous.” The reform language, Johnson said, was obviously meant to give incarcerated people a chance to reduce a penalty from mandatory life imprisonment to a lesser sentence of five to 50 years. Johnson also took issue with the majority-held view—that a sentence reduction was an executive branch power, and, therefore, the judiciary had no role. “It is axiomatic that establishing penalties for criminal offenses is the province of the legislative branch of government and that sentencing is the province of the judicial branch of government,” she wrote.

In 2015, Johnson got another chance to fight habitual offender sentences when Esteen filed a writ application to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal. He lost. Once again, Johnson dissented. In doing so, said a source close to the chief, she provided “a road map that he was able to use to win the issue.” (This person requested anonymity because they still maintain professional ties to the court.) Those around Johnson noticed that she would sometimes use dissents to communicate directly with incarcerated people in Louisiana, who have little voice, representation, or advocates in the outside world. Her willingness to take a strong stance on cases involving incarcerated people is particularly important in Louisiana, one of the most carceral states in the U.S. While it was true, Johnson wrote, that the 2001 reforms were prospective, subsequent legislation was retroactive. Old sentences, including Esteen’s—which she deemed illegal—could be reduced. Indeed, “the court in which the sentence was imposed may, at any time, correct a sentence that exceeds the maximum penalty authorized by law. The judiciary therefore has authority to amend its judgments after they become final as a result of the legislature’s reassessment of the appropriate penalties for an offense.”

Johnson was aware of the implication of her line of reasoning; it could potentially affect the sentences of hundreds of incarcerees. Unfortunately for Esteen, the majority of the court disagreed with Johnson, believing that, as Armstrong put it, the only remedy to correct this sentence was “an executive power,” such as the Risk Review Panel.

By 2018, however, the Supreme Court got in step with Johnson, who had recently thrown the court’s support behind the Louisiana Justice Reinvestment Task Force. Created by the state legislature—and stacked with lawmakers, judges, prosecutors, law enforcement officials, and attorneys—the task force sought to address the state’s unparalleled levels of incarceration, and to reform the bail system. Among its policy recommendations: a reappraisal of the habitual offender laws.

By this point, Esteen had been filing appeals for years. Now it was early 2019, and he hoped to overturn a dozen years of sentencing law precedent. This time, he was victorious. By 4-3, the justices found that district court judges had the power to immediately reduce sentences stemming from the draconian drug laws and habitual offender laws.

In her concurrence, Johnson took a victory lap. She reminded the court how long she had pushed to reduce these sentences. “I dissented in [State v.] Dick, believing the majority in that case ignored a clear mandate from the legislature. The majority in this case now corrects that error,” she wrote, concluding that Esteen and “similarly-situated inmates are entitled to seek relief through the courts.”

Esteen, however, did not win immediate relief. He remained at Angola, and two months later, a district court judge resentenced him to 100 years. Even as other incarcerated people were released because of the Supreme Court decision bearing his name, Esteen remained imprisoned.

It was the 100-year sentence that enabled his case to be heard by the parole board. On his way to meet the board, he was greeted by other prisoners at Angola. “You’re leading the way for all of us here,” one said to him. “Y’all be blessed, my brothers,” Esteen told them. The three-member board took into account that Esteen had earned a bachelor’s degree behind bars and was a model prisoner. “You have done all the things you’ve done without regards to whether it will please us or not,” a parole board member told him.

Esteen was free.

Johnson had been a prophetic voice on criminal legal system issues, but her final year as chief justice was perhaps her most profound on the bench.

On May 25, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic cut a swath through the U.S., Minneapolis police officers arrested a Black man named George Floyd for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes. Seventeen minutes later, Floyd was dead, pinned down by a white officer who had a knee on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, the largest racial justice movement in decades began across the country.

On June 8, Johnson wrote a letter to her colleagues on the bench, and in the executive and legislative branches of the Louisiana government. Johnson was set to retire at the end of the year, and this was one of her final opportunities to go on the record about racism embedded in the criminal legal system, and the role she and other judges played in this failure. The two-page letter displays a clear-eyed awareness about the racism in Louisiana’s criminal legal system, history, and that people protesting in the streets were driven in part by years of inaction from her profession:

“[T]he protests are the consequence of centuries of institutionalized racism that has plagued our legal system. Statistics show that the Louisiana criminal legal system disproportionately affects African Americans, who comprise 32% of our population in Louisiana, but 70% of our prison population. African American children in Louisiana are imprisoned at almost seven times the rate of White children. Our prison population did not increase fivefold from 7,200 in 1978, to 40,000 in 2012 without decisive action over many years by the legislature and by prosecutors, juries and judges around the state. We are part of the problem they protest.”

Johnson wrote that the criminal legal system was imperiled precisely because it appeared to value white lives over Black lives. “Is it any wonder why many people have little faith that our legal system is designed to serve them or protect them from harm?” she asked. “Is it any wonder why they have taken to the streets to demand that it does?”

In the concluding paragraph, she implored her colleagues “to spend some time reflecting on the ways in which we ask others to accept injustices that we would not.”

Associate justices were not pleased.

African American children in Louisiana are imprisoned at almost seven times the rate of White children. Our prison population did not increase fivefold from 7,200 in 1978, to 40,000 in 2012 without decisive action over many years by the legislature and by prosecutors, juries and judges around the state. We are part of the problem they protest.

Bernette Johnson Former Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court

The Future of the Court

In the months preceding the election to fill her seat, Johnson continued to issue opinions that tested the bounds of Louisiana legal doctrine. In June, she argued for a retroactive ban on split-jury verdicts, which were intentionally discriminatory and “disproportionately affected Black defendants and Black jurors.” (In April, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a life without parole sentence in Louisiana for Evangelisto Ramos, who contended that his conviction by a non-unanimous jury was an unconstitutional denial of the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial.) In August, Johnson issued an opinion regarding Fred Kidd Sr., a Black man convicted by a non-unanimous jury of attempted second-degree murder. “There are some rules of procedure untethered to our history of discrimination against African Americans where the question of retroactive application may carry less weight,” Johnson wrote. The non-unanimous jury rule was “intentionally racist.”

Until recent years, Louisiana was the only state where one could be convicted to a sentence of life without parole on a verdict of 10-2; in late 2018, voters ended the practice. Then in September, mere weeks before Fair Wayne Bryant was freed from prison, the chief took another whack at habitual offender sentencing: “Because drug laws and habitual offender sentencing provisions have been disproportionately used against African Americans, we exacerbate and normalize this disparity if we ignore it in our proportionality analysis under the Eighth Amendment.” (Jason Williams, the newly elected Orleans Parish district attorney, pledged to end the use of habitual offender sentencing.)

These robes would not be easy to fill once the chief stepped down. Three judges, all Black women, ran to replace Johnson on the seat that so many, including Ronald Chisom and the state’s Black legal establishment, fought so hard to secure.

The significance of Johnson’s absence from the court was hard to overstate. In October, Judge Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux of the Third Circuit worried that “many of the issues that she fought for, many of the ideas that she articulated—many of the inclusionary aspirations that she wrote about and spoke about—are going to become secondary.” That these issues had mattered to the court at all was a consequence of the power and influence Johnson amassed over several decades. “That is the power of being chief justice,” Thibodeaux said.

“She has been an unwavering yet sometimes solitary voice for civil rights for all, including some of the most marginalized communities across Louisiana,” said Kristen Clarke. “Her loss, it will create a tremendous void.”

Piper Griffin, who succeeded Johnson as judge on the Orleans Parish Civil District Court, won the election by default, after her remaining opponent dropped out.

Griffin, 58, met Johnson when she began practicing law in 1987. Johnson had a reputation, as a dedicated, intelligent jurist who, despite sitting on the state’s highest court, remained active in the community, Griffin told The Appeal late last year.

It was just after the election, and Griffin discussed how Johnson’s legal views tended to make her enemies rather than friends. It’s the curse, perhaps, of being near the law’s vanguard. As someone widely considered to be in Johnson’s mold, did Griffin find that worrisome?

She did not. “We live in very different times,” she said, noting that Johnson had had to fight simply to retain her seat and then to achieve her seniority. Griffin said that she would not have to engage in these fights because Johnson already fought them. “Do I foresee myself as someone who will have to fight battles? I don’t know.”

Marc Morial, Johnson’s longtime friend and supporter, expects a lot of the new justice. She will have opportunities to boldly stake her claim on the court, to ensure that her beliefs and convictions are enshrined in the books.

“My hope is that she will continue the principled jurisprudence of Justice Johnson and Justice Ortique,” he said. “If Justice Griffin has to write dissents—so be it.”