Commentary

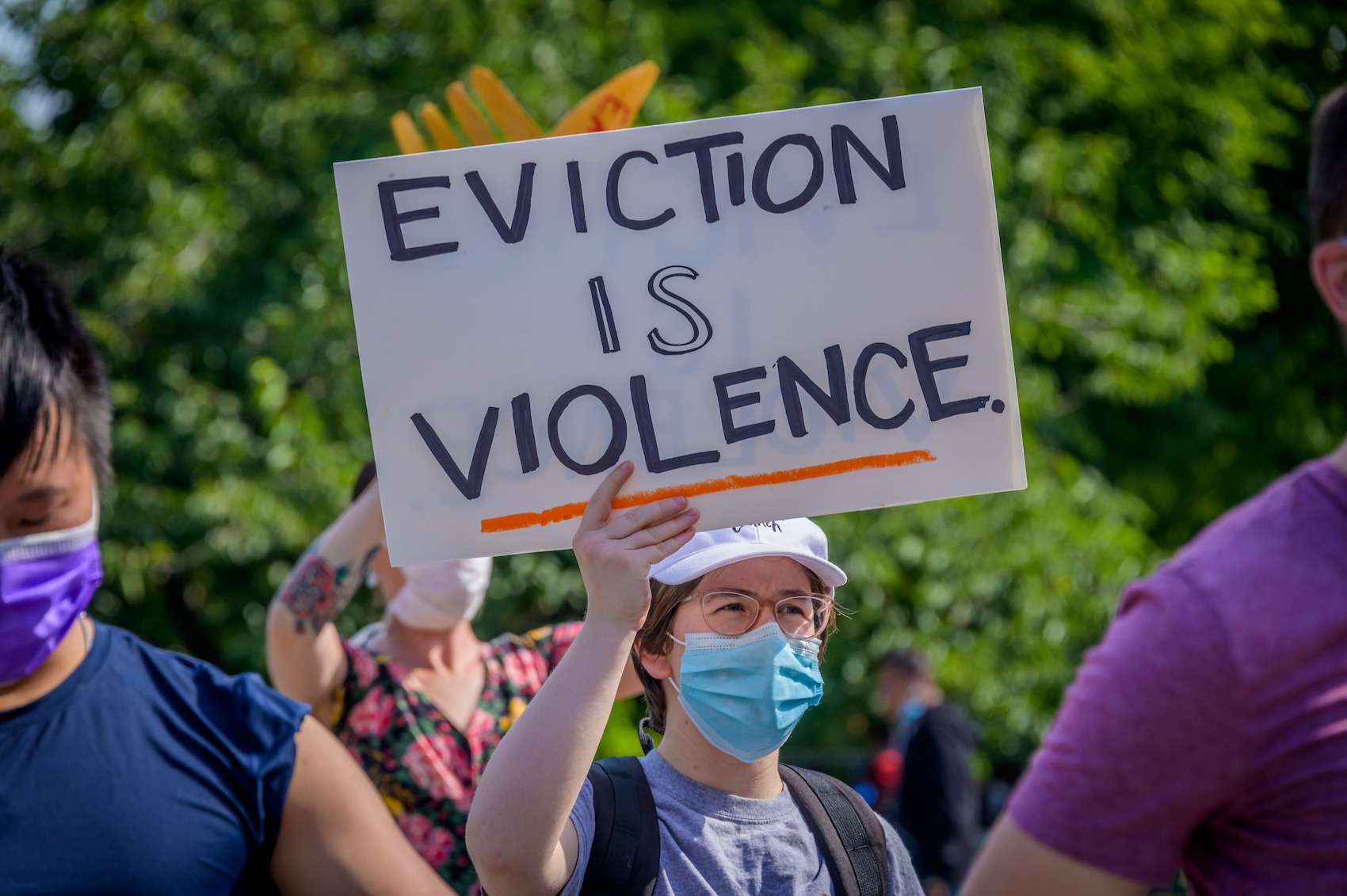

The Coming Wave of Evictions Will Significantly Worsen America’s COVID-19 Crisis

The CDC must immediately extend its emergency eviction moratorium to give the Biden administration and Congress time to provide additional emergency rental assistance.

Lost in the pandemic news coverage of risk-laden holiday travel and restaurant dining lies an event that could endanger far more lives: the expiration of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s temporary order to halt evictions. This order, which took effect on Sept. 4 and provided some protections against evictions after the CARES Act temporary moratorium expired, is set to expire on Dec. 31 unless the federal government takes immediate action. We are urging the CDC to immediately extend its emergency order through next spring to give the Biden administration and Congress time to issue a robust moratorium and provide additional emergency rental assistance.

The CDC issued the order earlier this fall, recognizing the danger evictions posed to public health and the spread of COVID-19. Although they’re rarely treated as such, evictions are a public health crisis. As we illustrate in our new article on pandemic housing policy, even the mere threat of eviction can increase stress levels, anxiety, and depression—all of which can weaken the immune system. Eviction disproportionately affects high-risk populations who experience greater rates of illness and infection, and can result in some of the comorbidities that make people more vulnerable to COVID-19 complications and mortality.

Compounding these underlying health issues, eviction results in transiency, homelessness, and crowded residential environments that increase both the frequency and proximity of contact with others and make it impossible to comply with pandemic mitigation strategies. Many who lose their homes will go to live with friends or relatives, increasing the risk of COVID-19 exposure for everyone in the home. In fact, studies of other contagious diseases have found that adding as few as two new members to a household can as much as double the risk of illness. People who are evicted may also experience decreased access to COVID-19 testing and medical attention because they are forced to move to poorer, underserved, and medically neglected neighborhoods.

While it has been clear for some time that COVID-19 disproportionately harms communities of color, the looming epidemic of evictions is also likely to most heavily burden nonwhite people. Prior to the pandemic, studies of various cities found that 80 percent of those facing eviction were from nonwhite households. In fact, Black households were more than twice as likely as white households to be evicted. But by far the most vulnerable are Black women, one out of five of whom report having experienced eviction and who, in many states, face eviction filings at double the rate of white renters.

We may be about to witness evictions on an unprecedented scale. The estimated rent shortfall is expected to surpass $24 billion by January. A study by the Aspen Institute estimates that 30 million to 40 million people in America could be at risk of eviction in the next several months, with some already being forced from their homes. Princeton’s Eviction Lab has been tracking evictions since the pandemic began and found that moratoriums work, dropping evictions as low as 83 percent below historical averages. In Massachusetts, for example, eviction filings have been on the rise since the state’s moratorium expired in mid-October. Similarly, filings in Richmond, Virginia, spiked as high as 395 percent above historic levels when the federal CARES Act moratorium expired. And emerging alongside these lapsed moratoriums is a foreboding trend: Incidences of COVID-19 have risen in states that lifted moratoriums at 2.1 times the rate of states that maintained them. Deaths increased by 5.4 times. In fact, as state moratoriums lifted, the United States has seen an estimated 433,700 excess cases and 10,700 deaths from COVID-19—due to eviction alone.

As we urge in our article, in order to protect everyone’s health during a pandemic, we must protect those most likely to contract, spread, and die from infectious disease. That means prioritizing people in poverty and people of color, who are more likely to be evicted and more likely to suffer severe health harms from COVID-19.

While the first step must be an extension of the federal moratorium against evictions, there is much more that we must do. State and local governments need to adopt robust moratoriums coupled with supportive legal and financial measures, such as rental assistance, eviction diversion programs, and civil right to counsel. They also need to embrace Medicaid expansion, which can offer permanent pathways to reducing and preventing eviction and associated public health harms. Local governments need to ensure tenant protections are enforced and implemented properly and that tenants know their rights.

Finally, the federal government could do much to prevent many individuals already on the knife’s edge of stability from losing their homes, their health, and even their lives by introducing a much-needed new round of assistance to people across the country facing the fallout from this moment.

Emily Benfer is a visiting professor of law at Wake Forest Law, founding director, Wake Forest Law Health Justice Clinic, and chair of the American Bar Association COVID-19 Task Force Committee on Evictions. Gregg Gonsalves is assistant professor of epidemiology at Yale School of Public Health, and an associate (adjunct) professor of law at Yale Law School. Danya Keene is associate professor of public health at Yale School of Public Health.