The Appeal Podcast: The Media’s Misguided Fentanyl Hype

With Appeal contributor Maia Szalavitz

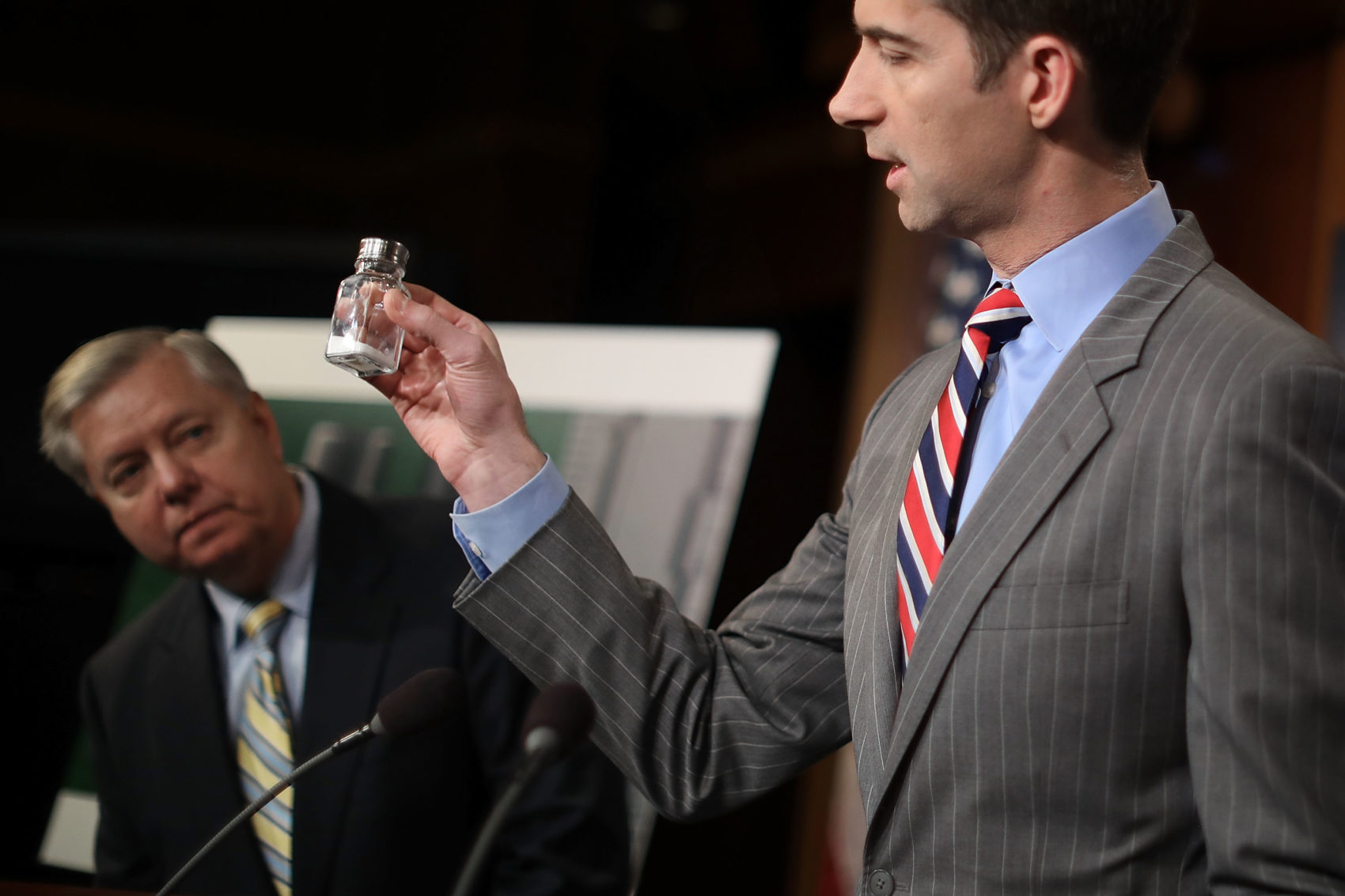

In recent years, lawmakers and the media have dusted off the 1980’s War on Drugs script to respond to an uptick in overdoses caused by a new, potent, heroin-like substance called fentanyl. Military officials are considering classifying it as a “weapon of mass destruction,” and highly regarded media outlets like 60 Minutes have spread the fable that police can be badly harmed from merely touching the drug. This week’s guest, Appeal contributor Maia Szalavitz, explains how medical professionals and reformers are pushing back against this media-fed panic.

The Appeal is available on iTunes and LibSyn RSS. You can also check us out on Twitter.

Transcript

Adam Johnson: Hi, welcome to The Appeal. I’m your host Adam Johnson. This is a podcast on criminal justice reform, abolition and everything in between. Remember, you can always follow us at Facebook and Twitter at The Appeal magazine’s main Facebook and Twitter page and as always, remember you can rate and subscribe to us on Apple podcasts.

In recent years, lawmakers and the media alike have dusted off the 1980s War on Drugs script to respond to an uptick in overdoses caused by a new potent heroin-like substance called fentanyl. The military calls it a quote “weapon of mass destruction” unquote. High status media outlets like 60 Minutes have spun wild fables about how the police are getting injured by merely touching the substance. This week’s guest, Appeal contributor Maia Szalavitz, explains how medical professionals are pushing back against the latest wave of media panic and government misinformation.

[Begin Clip]

Maia Szalavitz: The idea that we can interdict our way out of something like fentanyl, unless we want to completely have no trade with the outside world, it’s just ridiculous. It can’t possibly work because selecting for smaller and smaller and more and more potent drug leads to the situation where it becomes unenforceable. So this is not the way to deal with drug problems. We need to deal with why people are so unhappy that they are willing to take the risks of fentanyl these days.

[End Clip]

Adam: Maia, thank you so much for coming on.

Maia Szalavitz: Thanks so much for having me.

Adam: So you and Zach Siegel wrote an article for The Appeal criticizing media coverage of fentanyl.

Maia Szalavitz: Yes.

Adam: Which has now been deemed by some lawmakers as a “weapon of mass destruction” in a non ironic way, for those who were interested, it was not a joke. Can we actually sort of explain to an audience who may not know what fentanyl is and what its relationship to heroin is and what is the sort of scope of the public health issue with regard to fentanyl?

Maia Szalavitz: Sure. So fentanyl is an opioid compound that is about 50 times stronger than heroin.

Adam: Wow.

Maia Szalavitz: And there are a number of variants of fentanyl. So we really shouldn’t be talking about fentanyl we should be talking about fentanyls. So there’s carfentanil, which is like 10,000 times stronger and there’s all manner of variants in between. So obviously this can make dosing very complicated because if you are trying to go with a street substance that you don’t know whether it’s one times as pure or 10,000 times as pure, you can imagine that you could overdose on something like that very easily. And that is why these fentanyls are indeed a public health threat.

Adam: Okay. And so this fentanyl panic is now, like all panics it has some basis in reality. There is a public health concern with this.

Maia Szalavitz: Yes.

Adam: But it has now been, it’s gone from the realm of public health and science as these things typically are, to the realm of media demagoguery, posturing lawmakers. Your piece lists a series of examples of the media panicking over this baseless threat. I want to read something you wrote, you said quote, “On July 13 of this year, an ABC affiliate in Houston reported that two sheriff’s deputies ‘began to feel ill’ while collecting drugs that were found in a hotel room first spotted by the hotel cleaning service. After the officers administered Naloxone to themselves, which in the event of an actual overdose would be physically impossible because the victim would be unconscious, a hazmat team swarmed the hotel. A minor drug bust was turned into a scene from HBO’s Chernobyl.”

Maia Szalavitz: So let me set the scene here a little bit because what happened there was the deputies came in, they saw that fentanyl was involved and they freaked out. So they started having what was basically a panic attack. And the symptoms of fentanyl overdose are nothing like this. If you are overdosing on fentanyl you are immediately unconscious. Now, sometimes you might have the ability to grab your mouth because you may have a side effect where you suddenly stop breathing because fentanyl stops breathing a lot faster than other opioids do, but rarely you even get that. So if you are administering Naloxone to yourself, you are not experiencing an overdose because you would be unconscious and unable to complete that action if that was what was going on.

Adam: By definition.

Maia Szalavitz: Yeah, exactly. And so the fear that comes from fentanyl is that these little white powders will waft into the air and because it’s so potent it will go up your nose and suddenly you will overdose. And there’s even been these ridiculous things going around Facebook where people are like ‘wear gloves at Walmart because there’s fentanyl on the handles of the shopping carts.’ Now if this were the case, people who are addicted would go and put their hands all over shopping carts so they could get high right?

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: Obviously that’s not happening because you have to shoot the stuff to actually get high on it. So if you are not injecting or snorting fentanyl deliberately, it is extremely unlikely that you are going to be able to overdose on it. Now, there was an incident in Russia actually where they used aerosolized fentanyl to deal with a terrorist situation and knock people out. This is the only instance ever of fentanyl being weaponized and it had to be done deliberately.

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: Like you had to make it into this super fine powder, which requires a lot of technology in order for that to work. Drug dealers do not use that technology because they don’t want people to get high for free.

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: The reality is that drug dealers are business people. Now you have stupid people in any field and sometimes you may have somebody who thinks, ‘well, maybe I’ll put a stronger version in there to hook people,’ but if you thought about that for a minute, you would realize that if you were to do that, you would have to brand the product otherwise people wouldn’t know what they were hooked on and they wouldn’t know what to ask for. So it gets really ridiculous. But the fear has been that a police officer will go into a scene, they will be exposed to fentanyl floating around the air, they will pass out or they will touch an overdose victim, get fentanyl on them and therefore overdose. Again, if this were possible, people would be touching overdose victims to get hot. This again, is not what happens.

Adam: Yeah. We have a very clear way of testing this theory.

Maia Szalavitz: Exactly. And I mean there is a guy, he actually videotaped himself touching fentanyl and having zero effect.

Adam: So, and of course the people who are in charge with actually studying this who are relatively independent, the American College of Medical Toxicology, they’ve released statements, several statements saying that touching elicit fentanyl does not make you sick or carry any significant health risks. You know, there’s all this talk about fake news and it’s, I think for the average kind of open-minded media consumer, even for me, who criticizes media for a living, it is pretty shocking — if not upsetting — the degree to which 60 Minutes endorses this idea that you can touch fentanyl, ABC News, all these sort of, based solely on what police sources tell them. But you’re saying that there is no credible medical expert or scientist who backs up this? Correct? Is that a fair-?

Maia Szalavitz: Yeah, absolutely. I mean the medical people know that fentanyl is used in operating rooms all the time. And if, yeah, that is a liquid form of it but nonetheless, if it were wafting out and you know, knocking out anesthesiologists, we would know about it. This does not happen. You have to deliberately get high on this stuff. And the police are rightly scared of a drug that’s so potent that you can overdose on micrograms of it, but the only protection you need, and you really don’t even need this, is gloves. But people are dressing up in these hazmat suits to like deal with overdose victims. And the thing that is really problematic about that is that it takes time to dress in these things and time equals brain for people who have overdosed. So in other words, the longer the brain goes without oxygen, the more likely there is to be severe damage and death. If a brain goes without oxygen for I think it’s six minutes, you will either be extremely brain damaged or dead. So these seconds really, really count. And if you have to suit up, you may be basically the difference between life and death for a person.

Adam: Right. So this is one of the things I wanted to establish that that it’s not just the public panic leading to bad public policy, that there are real short term stakes here vis-a-vis how first responders handle people who are overdosing. Is that correct? Like they have to put on the hazmat suits and do the whole rigmarole while someone’s dying.

Maia Szalavitz: Right. And it’s completely unnecessary. The interesting thing about the incident that we were discussing earlier is that the police went in there after a house cleaner discovered the scene. If the house cleaner, who knew nothing about what was going on at all, why didn’t she overdose?

Adam: And it seems like the media as you note in pretty good detail — definitely read the story there’s tons of examples here — has just taken a cue entirely from these kind of mindless police representatives.

Maia Szalavitz: Well, and I want to say that like you can understand why the police might be scared. First of all, they’re taught that people with addiction are evil, scummy, bad people and they have often had bad interactions with people with addiction. And so you end up with, they don’t like these people very much to begin with and now they may be threatening their lives. Why do you want to risk your life to save somebody that everybody else sees as trash? And that’s the bottom line with this. This is really all about the stigma.

Adam: Yeah. That they’re subhuman. Yeah.

Maia Szalavitz: You know, and the police, you can mentally think yourself into some very severe physical symptoms. I think we demean it to say “panic” in a sense because panic actually has real physiological outcomes and you know, people can pass out from panics. So the thing that will work too remove this problem is to have accurate information so that when you go into a situation where fentanyl might be present, you don’t freak out because you don’t think that, ‘oh my god, a molecule of it is gonna get on me and I’m going to die.’

Adam: I mean this reminds me a lot actually of the, we talked about the physical manifestation of panic, around the so-called sonic attacks in Cuba against the US State Department where scientists looked at this and realized it was crickets, but for a couple of years they were studying it. And every scientist coming back saying there is no objective evidence this is true. But it was a case, you know, it was a social contagion.

Maia Szalavitz: What was interesting there though was that there were findings on brain scans of people, but I mean we don’t know what happened there. And you know, it could be crickets, it could be something else, but if you’re seeing people having serious symptoms, I think it’s definitely worth investigating. The thing with fentanyl is different however, because people are not, you know, cops are not showing up with brain damage. We are not seeing EMTs overdose and die.

Adam: Well I meant, what I mean is the extent to which physical, that the police who are citing these symptoms, they are manifesting some physical symptoms. Right? Like if I had the police union lawyer here, he would say, you know Joe, Bob, Officer Bob was doing X, Y and Z. Is that just a product of them sort of talking themselves into it?

Maia Szalavitz: Yeah, I mean the symptoms they tend to have also tend to be not symptoms of opioid overdose because basically symptoms of overdose include unconsciousness, slowed breathing, pinpoint pupils. It’s not panic generally because opioids are depressants and they make you mellow and calm typically. So usually when you die of an opioid overdose, you would slowly basically stop breathing. Now fentanyl is slightly different in that in some cases rather than that happening, it instantly stops breathing. And that can give you, you know, half a second of panic before you pass out. But the general course of an opioid overdose is breathing sort of slowly stopping.

Adam: So let’s, I want to switch gears here and talk about the public policy implications of this. So there was an emergency effort to make fentanyl a schedule one narcotic in 2018 by the FDA. You write that quote, “There is scant evidence that scheduling a substance leads to a substantial reduction in use.” Can you explain what the science says about our kind of throw the book at them approach to drugs and saying, okay, let’s say that there is a real overdose crisis or there’s a fentanyl crisis in some ways and that’s, you know, something that’s real. And the response — as is the response with everything in the United States and the whole reason why there’s even an Appeal or a Justice Collaborative — is to make laws for things and they make things illegal and to put people in jail. Can we talk about what the science says about this approach and how you think it should be handled?

Maia Szalavitz: Sure. So our scheduling of drugs is not based on science. It’s based on racism. There’s no scientific way you can put heroin, LSD and marijuana in the same category and say that they have no medical use because it’s simply not true. And they are extremely different drugs with extremely different effects. And for example, LSD is very, very, very rarely addictive. It’s almost impossible to overdose and die on it. You can overdose and trip for a very long time, which may not be very pleasant, but you’re not going to die. Whereas you can definitely overdose on heroin quite rapidly. Marijuana is physically impossible to overdose on. So again, like having a category that has all of those three things in it, is due to a contingent racist history of regulation by panic.

Adam: Right. And so obviously that’s not, that’s not very empirical.

Maia Szalavitz: Yeah. It’s based on nothing. And the idea that we’re going to say, ‘okay, we’ll schedule everything that is a derivative of fentanyl.’ Okay. What if one of those things happens to be the cure for cancer and we haven’t discovered it yet because there are all these derivatives that we don’t even have a clue what they are and they’re being pumped out of elicit labs at the moment? It’s a real problem for the pharmaceutical industry because as soon as you make something schedule one, it becomes almost impossible to research. And this is a really sad thing with regards to marijuana because there have been for years, there have been hints that it may be helpful for Alzheimer’s, which is something we have absolutely nothing for. And yet people have avoided researching it and avoided investigating that. I mean, I’ve talked to scientists who have said ‘yes, uh, you know, I found some really interesting things about this, but it’s just too much of a pain in the butt and too expensive and too difficult to deal with so I will look for other things.’ So, you know, just randomly scheduling an entire sequence of substances is absurd. And it also doesn’t change things really. What happens is we schedule something, they immediately move on to the next thing, we don’t know if it’s more dangerous or less dangerous. They move back to some of the other things and with fentanyls this is the perfect drug for the Internet age because it’s really tiny, it doesn’t smell very strongly and you could have the amount you needed to dose everybody with an addiction, you know, sitting on your desk and not very visible. So the idea that we can interdict our way out of something like fentanyl, unless we want to completely have no trade with the outside world, is just ridiculous. It can’t possibly work because selecting for smaller and smaller and more and more potent drugs leads to this situation where it becomes unenforceable. So this is not the way to deal with drug problems. We need to deal with why people are so unhappy that they are willing to take the risks of fentanyl these days.

Adam: So let’s talk about that cause I think someone listening would say, okay, fentanyl is a real issue. If you were made a dictator of the United States tomorrow, what would be your approach to this? To the extent to which we acknowledge that it’s a crisis, what would your regime do?

Maia Szalavitz: Well, first of all, I would decriminalize possession of everything.

Adam: Right. Okay.

Maia Szalavitz: There is absolutely no sense in locking somebody up for possession of a substance. It doesn’t help treatment, it doesn’t help, punishment does not solve the problem. All we do is recycle people through the system for a couple of days. It actually increases their risk of dying of overdose because we don’t treat them while they’re in there and it just wastes hundreds of millions of dollars every year. So first of all, just decriminalize possession, period. Now obviously we don’t want Phillip Morris Fentanyl.

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: That would be really bad. And we have seen what happens when we allow drug companies to wildly promote opioids.

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: It should never have been legal in the first place for oxycontin to be promoted the way it was, but what they did, most of it was legal. And that is terrifying and bad. So what you want to do is figure out the sweet spot between controlling access to the substance and developing a black market. And you have various tools to do that which involved, for example, prescribing heroin or even dilaudid or something like oxycontin to people who are addicted so that at least if they are trying to avoid overdose they can. You suddenly get what you wanted and now you suddenly have tons of time in your life and no more cops and robbers. You have the source. You don’t have to spend 24/7 trying to get the drug and dealing with what you need to do in order to do that. Instead you have the drug, you pick it up and that’s it. That suddenly leaves space for people to be with their families, get a job. All of the kinds of things that we would like them to do. The other aspect of it is simply pharmacology because if you have an opioid in your system, you are not going to be continually craving it as you would if you have no opioids in your system and you are dependent on it. And there have been studies in other countries where they have prescribed heroin and they have prescribed dilaudid and it’s interesting because you would think, oh my god, everybody with addiction will immediately want a heroin prescription because they think that’s okay going to be exactly what they want and they’re problems will be solved and everything will be good. In fact, only about up to 8 percent of people who are addicted to opioids end up with prescriptions for heroin and other desirable opioids when there’s methadone and buprenorphine available in the system without too many constraints. So you need to like create the sweet spot where you’re not like putting heroin in the water supply and giving it out to children with their lunch, but you’re also not driving people to street fentanyl.

Adam: Right.

Maia Szalavitz: Basically for the people who are on the very severe end of the addicted spectrum, if you provide heroin to them, what often happens is just what happens to anybody else when they get anything that they thought would solve their life. It doesn’t solve your life. You suddenly have to face the problems you actually have. And this actually is why it helps people get better.

Adam: I assume people in this world, medical experts, people who are trying to reform our carceral approach to drugs are kind of banging their head against the wall, trying to get media, Hollywood, lawmakers to look at the science. Is there any indication that there’s space being opened up to listen to this and not just take cues from law enforcement?

Maia Szalavitz: Well, Zach and I and a couple of other people founded an organization called Changing the Narrative and you can find it on the web at changingthenarrative.news, N-E-W-S. And we are trying to provide sources and accurate information so that journalists who cover this can do so in a responsible and useful way. The thing about these panics is that people tend to think this stuff is too good to check and that is not an appropriate response to a story of a law enforcement officer saying that they touched fentanyl and now they’re overdosing. There’s another aspect of this, which is that somebody might say they overdosed by touching fentanyl in order to hide the fact that they are actually addicted.

Adam: Yes. There is a couple of instances where it’s clear that someone, yeah, that, that this is someone who’s using or abusing and then they had the sort of retcon their evidence of having-

Maia Szalavitz: Yes, exactly. So, that’s another aspect of this. But in terms of better coverage in this area I think, you know, the early Internet was really great for this because for so long the only information people had access to was government propaganda as filtered through the media. And once the Internet came along and people could actually look at the medical research for themselves and look at the scholarly literature in say sociology and criminology and all across disciplines you could suddenly see that a lot of what we were being told about drugs is nonsense. Now we just need the media to hook up with the very interesting and exciting sources that can give you really good drugs stories without this absurdity and panic.

Adam: Okay. Well, um, I think that’s a good place to stop. Um, everyone definitely check out changingthenarrative.news and definitely check out the article she wrote with uh, Zach Siegel at theappeal.org. I think this was super great. I learned a lot and I really appreciate the work you do, so thank you for coming on.

Maia Szalavitz: Oh sure. Thanks. And likewise.

Adam: This has been The Appeal podcast. Thanks to our guest Maia Szalavitz. Remember you can always follow us on Twitter and Facebook at The Appeal’s main Facebook and Twitter page and as always you can like and subscribe to us on Apple podcasts. The show is produced by Florence Barrau-Adams. The production assistant is Trendel Lightburn. Executive producer Cassi Feldman. I’m your host Adam Johnson. Thank you so much. We’ll see you next week.