The Appeal Podcast: The Backlash Against Expanding Voting Rights

With Appeal staff reporter Kira Lerner

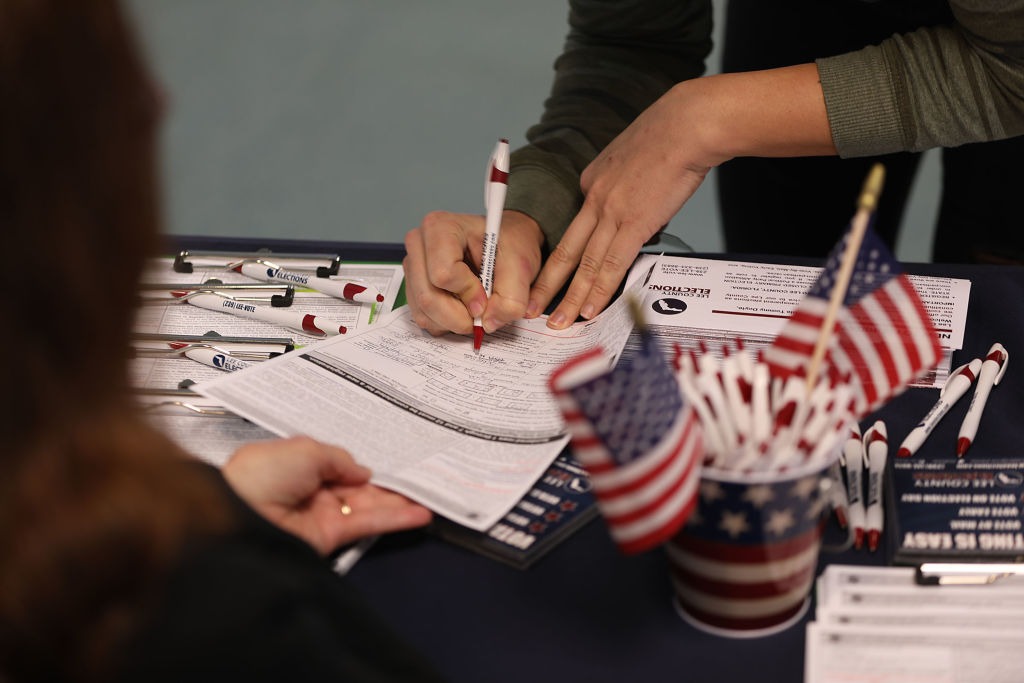

States throughout the U.S. have recently expanded voting rights to millions of people with felony records previously barred from participating in elections. After a brief moment of celebration, two of them, Iowa and Florida, are now experiencing backlash from Republican lawmakers advocating for policies that would curtail those rights. This week, we are joined by The Appeal’s Kira Lerner to discuss the hurdles these movements still face and the forces pushing back against the wave of increased enfranchisement.

The Appeal is available on iTunes and LibSyn RSS. You can also check us out on Twitter.

Transcript

Adam Johnson: Hi, welcome to The Appeal, a podcast on criminal justice reform, abolition and everything in between. Remember, you can always follow us on The Appeal’s main Facebook and Twitter page and you can always rate and subscribe to us on iTunes.

A recent wave of amendments and governors’ orders throughout the United States has expanded enfranchisement to millions of voters previously barred from participating in elections. After a brief moment of celebration two such places, Iowa and Florida, are experiencing legislative backlashes against moves to expand voting rights to those convicted of felonies. This week we are joined by The Appeal’s Kira Lerner to discuss the hurdles these movements still face despite overwhelming electoral victories.

[Begin Clip]

Kira Lerner: People are kind of all over when it comes to what effect the restoration of civil rights will actually have. Florida disenfranchised over 1.5 million people and one third of those were Black, which meant that one in four Black adults was disenfranchised, which is really huge amounts of the African American population in Florida when you think about it.

[End Clip]

Adam: Thank you so much for joining us.

Kira Lerner: Thanks for having me.

Adam: So we are talking about felony voting rights. There’s been lots of moves recently. We’re starting to see some of the, for lack of a better term, to fruits of Black Lives Matter bear legislative victories. One of the major ones, one of the sort of highlights of election night 2018 was the passing of Amendment 4 in Florida, which you are writing about. Can you tell us about what this meant and more importantly, what it didn’t mean and how some of the Republican lawmakers, I think it’s fair to say Republicans, are pushing back against Amendment 4, which theoretically, at least the headline says, granted people convicted of a felony the right to vote?

Kira Lerner: Yeah. So as most people probably know by now, Amendment 4 passed in November on the ballot with almost two thirds approval, roughly 65% of Floridians voted to undo the state’s permanent disenfranchisement policy, which had been in place since after the Civil War. So this was really a big moment in Florida politics and for the whole country, Florida disenfranchised more people than any other state in the nation and had one of the strictest policies.

Adam: Right.

Kira Lerner: So this was really a big moment that advocates in Florida who worked really hard on this for many years had a lot to celebrate. The amendment officially took effect in early January and rightfully so there were a lot of people going to register for the first time. People were celebrating. Desmond Meade, who led the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, the biggest organization that pushed for this amendment, he held a press conference at the polls and brought friends and family and it was a really celebratory day. But since then things have gotten a little more muddled and confused. Desmond Meade and the advocates at the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, they wrote this constitutional amendment in a way that would be self actualizing. They said that this constitutional amendment would not need any legislation to take effect, but Florida lawmakers, a number of Florida lawmakers, are disagreeing with that point and they’re saying that there needs to be some kind of clarifying bill or clarifying language that they have to work out during this next legislative session before Amendment 4 can actually take effect. Uh, so a few things that lawmakers are concerned about that they’re going to be looking at in this next session, which starts on March 5th, they’re going to be looking at what the definition of murder should be. Amendment 4 does not include anyone convicted of murder or violent sexual assault. Those people will still lose their voting rights for life. Members of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition say that only first degree murder should be included in that. Some lawmakers are saying, ‘well, maybe that’s not what the voters attended. That’s actually not one murder means under Florida statute. What about vehicular homicide? What about someone convicted of a partial birth abortion?’ So there’s all kinds of things that could be included in this, and I expect that we’ll see some debate when this actually comes before the legislature. There’s also a few other issues about how this will actually be implemented. The county supervisors of elections don’t actually know who’s qualified and who’s not under this amendment.

Adam: Oh really?

Kira Lerner: So they’re going to go ahead and let anyone register to vote who wants to register to vote, which was probably the way that it should be. The supervisors of elections don’t have the power to tell people whether they’re registered or not. They don’t have that information. But there are concerns that someone who does not know that they’re not actually eligible, will go try to register to vote and will be committing another crime by doing that and being incorrect and could eventually be prosecuted for voter fraud.

Adam: Yeah, so it’s, it’s fair to say that in general, and this is true in other states as well, which we can talk about, that and I know we’re, we’re a nonpartisan show, we are not trying to advocate for one party or the other, but I think it’s probably a neutral observation, a totally objective, neutral observation to say that the general ethos is Republicans want to make it as difficult as possible for minorities to vote. Is that, would that be a fair statement to make across the board?

Kira Lerner: Most of the voter suppression that we’ve seen in this country has been from the Republican side, but something interesting to note is that Amendment 4 did have broad bipartisan support and that’s the only way that it got 65% approval. It was with support of people on both sides.

Adam: Right. It seems like a lot of these laws that are passed that try to expand enfranchisement, they try to nickel-dime them to death. It appears to me what’s going on, there’s a similar situation in Iowa, a state that doesn’t get a lot of attention except for about a six month period every four years, but this was, this was an article you wrote on February 7th called “Iowa Moves Towards Expanding Voting Rights. But It May Require a ‘Modern Day Poll Tax.’” Again, a poll taxes is part of the similar ethos of just making people jump through hoops in order to vote. The general idea is that you will have less African American voter turnout. Can we talk about the hurdles that are going on in Iowa and specifically how the modern poll tax is manifesting as having to pay off fines no matter how obscure?

Kira Lerner: Right. So after Amendment 4 passed in Florida, there were three remaining states that still permanently disenfranchised people with felony convictions for life. Those three states included Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia. Uh, we can go into each of those quickly. But to focus on Iowa first, Iowa does disenfranchise more than 50,000 people because of felony convictions. There’s been litigation in the state to try and undo that policy. It has not been successful. The State Supreme Court essentially ruled that it was constitutional what was going on. So this year, Governor Kim Reynolds publicly stated that she is going to support a constitutional amendment to undo the state’s permanent disenfranchisement policy, which is a pretty big deal. As you noted, Republicans are not usually supportive of policies like this and Kim Reynolds is a Republican. Uh, she personally has a criminal record which could play into some of her support for a second chances. Uh, that’s the language she uses a lot about this policy. She says that people deserve second chances.

Adam: Interesting.

Kira Lerner: Yeah. She was convicted of two different driving while intoxicated charges earlier in her life and spent time in rehab and she says, got clean and has kind of come to realize the importance of things like this. So there’s been a proposal in both houses of Iowa’s legislature to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot, just like in Florida, to undo the state’s policy and to automatically restore voting rights to more than 50,000 people. The issues that we’re seeing in Iowa are from certain lawmakers who want to make it really difficult for people to qualify under a potential amendment. And some local groups in Iowa and some Republican lawmakers are saying that a constitutional amendment should require that people pay off all of the fines and fees and restitution that’s included in their sentence.

Adam: Right.

Kira Lerner: And I talked to one man in Iowa who was convicted of vehicular manslaughter almost two decades ago, and he was ordered to pay $150,000 in restitution. So essentially he’s going to be paying, he’s going to be making monthly payments for the rest of his life. And he is always on time with those payments, he completed all other terms of his sentence, but if a constitutional amendment includes the requirement of paying off that restitution, he will never be qualified to vote for the rest of his life. And he told me how upset that makes him, how he feels like he’ll never have a voice and he’ll, he’ll never matter again. And like you mentioned before, a lot of advocates, a lot of voting rights advocates consider something like this, a modern day poll tax. Uh, we thought that the poll taxes of the Jim Crow era went away with the Voting Rights Act but if we are requiring people to pay off massive sums of money in order to cast a ballot, a lot of advocates say, how is this any different?

Adam: Right. I made a generalization about Republicans earlier that is mostly true. I think one qualifier is the degree to which the Christian or Evangelical Christian community had some support with Amendment 4. How involved are they in this process and how involved are they in the process in Iowa? I’m, I’m curious to what extent this, I know that some prison reform in general is being supported by Christian groups, can we talk about how they’re playing into this or to sort of tip the scales?

Kira Lerner: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the proposal in Iowa is still very early, so we haven’t seen a lot of support or opposition at all either way. But I’m sure there will be Christian groups who, like in Florida, will use language of second chances and come at this from a religious perspective in order to support the restoration of civil rights.

Adam: So ow can we broaden out here? I’m curious, cause you mentioned this offline, how many states in general presently disenfranchise those convicted of felonies to some varying degree?

Kira Lerner: Yeah, so there’s a scale across the 50 states. We have two states in which you never lose your right to vote. In Maine and Vermont you can vote even while you’re incarcerated. And there’s a number of states right now that are looking at legislation to join Maine and Vermont. I think New Mexico became the first state to move forward a bill that would allow people to vote even while incarcerated. So that’s on one end of the spectrum.

Adam: I find it curious, I want to note that Maine and Vermont, in addition to being the two states where you can always vote, are incidentally, by sheer coincidence, also the two whitest states in the union. Vermont has a white population of 96.2 and Maine has a white population of 95.5. So I’m sure that’s just a coincidence, but go ahead. I apologize.

Kira Lerner: Yeah, that’s an important point as well. So on the other end of the spectrum, we have Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia, which are the three states that still permanently disenfranchise for life. And Virginia is an interesting one because former Governor Terry McAuliffe tried to make the process automatic, ultimately failed, but he individually restored the rights to over 170,000 people. So Virginia is not always included in that ultra restrictive category just because the governor is really active in restoring rights. Northam has done the same thing. He actually put out a press release in the end of February touting how he’s done all of this work and a lot of people pointed to the timing, which came right after, right when he was in the midst of his blackface controversy and a lot of people were like, ‘this is what you should be doing anyway, this is what the previous governor was doing, you’re not announcing anything new.’

Adam: Yeah.

Kira Lerner: So that’s what’s happening in Virginia. There’s also roughly a dozen states where you lose your right to vote until you finish your sentence, and some of them include some amount of waiting period after that. Alabama, for example. Louisiana, until recently you couldn’t vote until you’re finished probation or parole. Legislation was passed in Louisiana last year that ended that. So now, as soon as you complete your sentence, you can have the right to vote. The majority of states fall into that category. You lose your right to vote while you are serving your sentence, but you have automatic restoration once that period is over. So we see every state has wildly different policy making this a very complicated system and states really range all across the board.

Adam: Now, obviously, as we touched on earlier, you can’t really talk about felony voting rights issues without talking about race. Obviously it is a proxy for disenfranchisement of African Americans. I know that in Florida, 20 percent of African Americans who would otherwise be eligible to vote can’t vote because, prior to the passage of Amendment 4, so I want to sort of establish the stakes here. Do, do we have a sense of if all of these laws were to disappear tomorrow, the sort of totality of enfranchisement for African Americans, is it, I mean, how big are we talking here and, and, and how does this compare to sort of prior expansions of enfranchisement in this country?

Kira Lerner: Yeah, people are kind of all over when it comes to what effect the restoration of civil rights will actually have. Like you mentioned, Florida disenfranchised over 1.5 million people and one third of those were Black, which meant that one in four Black adults was disenfranchised, which is really huge amounts of the African American population in Florida when you think about it, especially when you think how close these 2018 races were in Florida, both the senate race and the gubernatorial race came down to just tens of thousands of votes. But there’s a lot of people who will say that people with recently restored rights are not as likely to register to vote and to actually cast a ballot and just small numbers of them will show up at the ballot box because they don’t have a pattern and practice of voting every election day. So it’s hard to predict how this will affect elections, but I think we have to kind of think about the potential it has and if there are massive Get Out the Vote efforts and voter registration drives, given the sheer numbers of people who are disenfranchised, it really does have the potential to impact elections. Iowa is a fairly small state and with 52,000 people disenfranchised, Iowa is also a largely white state, and not as much as Maine and Vermont, but the disenfranchised population is also disproportionately African American. So we know that people who are disenfranchised are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates. And we can expect that that’s the way it would go in most of these states.

Adam: Yeah, it seems like Florida, the consensus is because Florida is always a very razor thin state for presidential elections and even Senate elections, that it could actually have some balance tipping abilities. Um, but again, it’s not, it’s not like they’re cheating or playing the game on god mode. They’re just giving people the right to vote that should have had it before.

Kira Lerner: Right. If you think of anything is cheating, it’s probably the policies that were passed after the Civil War that specifically disenfranchised African Americans.

Adam: I like when people frame enfranchisement as some sort of cheat, like where they’re like, ‘oh, well they’re driving poor people to the polls.’ And I’m like, okay, like is that bad? Um, so what are the forces that are trying to finally get rid of this sort of Civil War and Jim Crow vestige, specifically in Florida and Iowa, like what is the current status and what groups are working to move the needle on this?

Kira Lerner: Yeah, I think Florida is such a good example of the power of activism when it comes to this issue. Amendment 4 was led entirely by activist groups that had been on the ground for many, many years. Desmond Meade, the president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition who I mentioned before, he started out just knocking on doors, seeing if there was support for a constitutional amendment and years later he gathered enough signatures to put this on the ballot and then gathered enough support to have this pass. Like I said, this was an example of the power of activism and I think a lot of other states are noting how that happened and are really encouraged by how at a time when the system does not feel democratic in a lot of ways, this is a way that people can have a say and elections can matter and there aren’t a lot of examples of ways that elections really feel reflective of the will of the people and this is one way. So I think we’re seeing activists in Kentucky and Iowa trying to undo their permanent bans. We’re also seeing activists in some of the more progressive states trying to make their policies even more progressive. There are so many states that we think of as really progressive on voting rights, New Jersey and New York for example, that have pretty restrictive policies when it comes to which populations can vote. So in New Jersey for example, they’re thinking about ways that they can bring even more people into the democratic process, people who are on parole and probation and who might still be serving out part of their sentence. So activists are working on this across the country and I think it’s an issue that we should be watching really closely.

Adam: Yeah, I know the ACLU has been behind a lot of these and um, it’s interesting to watch these Evangelical groups and the ACLU team up, but I, I guess, uh, you know, strange bedfellows.

Kira Lerner: Right.

Adam: All right, well this was, this was great. Um, I know I learned a lot. I hope our listeners learned a lot. Thank you so much for coming on.

Kira Lerner: Thanks for having me.

Adam: Thank you to Appeal contributor Kira Lerner. Remember, you can always check out The Appeal on iTunes where you can rate and subscribe and as well as follow us on social media at The Appeal magazine’s main Facebook and Twitter page. This show has been produced by Florence Barrau-Adams. Production assistant is Trendel Lightburn. Executive producer Sarah Leonard. I’m your host Adam Johnson. Thank you so much for joining us. We’ll see you next week.