Virginia Prosecutors Fight to Uphold Life Sentence for Man Found Not Guilty

Even though a federal jury found Terence Richardson not guilty of murder, he was sentenced to life in prison. Virginia prosecutors want to keep it that way.

In 1998, someone shot and killed police officer Allen Gibson in the woods behind an apartment complex in the small town of Waverly, Virginia. Police arrested Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne for Gibson’s murder days later—despite a lack of physical evidence linking them to the crime and the presence of another possible suspect.

In 2001, a jury found them not guilty of murder. A judge sentenced them to life in prison anyway.

Richardson and Claiborne have been fighting to prove their innocence ever since.

In February, the Virginia Supreme Court gave Richardson a chance to make his case by ordering a new hearing to examine potentially exculpatory evidence. Richardson’s legal team says this material was never shared with his original defense attorneys—a violation of a U.S. Supreme Court decision known as Brady v. Maryland. (Richardson’s case is following a separate procedure than Claiborne’s.)

The innocence claim centers around three pieces of evidence: an anonymous call to a police tip line identifying someone other than Richardson as a suspect, a photo lineup administered to a 9-year-old witness, in which she identified a suspect other than Richardson, and a statement made by her on the day of Gibson’s death in 1998 describing someone whose hairstyle did not match Richardson’s.

At the hearing in Sussex County Circuit Court this May, Richardson’s legal team set out to prove that this evidence could have changed the outcome of the case. But they were derailed by what Richardson’s attorneys have characterized as a deliberate effort by state prosecutors and federal law enforcement officials to undermine Richardson’s innocence claim.

“Terence and Ferrone are innocent,” Jarrett Adams, co-founder of Life After Justice and lead attorney for both Richardson and Claiborne, told The Appeal. “They are not innocent by accident.”

For Richardson and Claiborne, the hearing was perhaps their best chance to bolster their innocence claims with recently unearthed evidence. But ultimately, the judge allowed only one item to be admitted as evidence before the Virginia Court of Appeals—the same court that had previously dismissed his case. With Richardson’s case now once again set to go before the potentially unfriendly Appeals court, his legal team fears he faces an uphill battle to prove his innocence.

“We’re up against the impossible,” Adams said.

When police arrested Richardson in 1998, he was facing the death penalty. Afraid of potentially putting his life in the hands of a white jury in the South, Richardson, who is Black, took a guilty plea for involuntary manslaughter and was sentenced to 10 years in state prison. Claiborne, who is also Black, took a plea deal on a misdemeanor charge, as an accessory to Richardson’s crime.

But after outcry over what Gibson’s family viewed as a lenient sentence, federal prosecutors brought additional charges against the pair, accusing them of selling crack cocaine and murdering a police officer during a drug deal gone wrong.

In 2001, Richardson and Claiborne went to trial in the federal case. A jury found them not guilty of Gibson’s murder, but guilty of selling crack. In an unusual move, federal judge Robert Payne sentenced Richardson and Claiborne to life in prison using “acquitted conduct sentencing,” a legal mechanism approved in a 1996 Supreme Court ruling, which allows judges to sentence defendants based on charges for which they were acquitted. In April of this year, the U.S. Sentencing Commission passed changes to federal sentencing guidelines to prohibit acquitted conduct from being used in sentencing guidelines.

As Richardson’s legal team built his case, they’ve focused on three pieces of evidence they say could have changed his fate.

When Gibson described his attackers to first responders shortly before his death, he said the man who shot him was tall and had dreadlocks. Richardson was several inches shorter than Gibson and had cornrows.

The 9-year-old girl, Shannequia Gay, was playing outside with her cousin when she saw a police car stop outside the apartment complex, according to a statement the child gave to police hours after Gibson’s death. Gay said she saw a police officer walk into the woods, then she heard a loud noise that scared her. When she walked closer to the woods to get a better look, she said she saw Gibson on the ground and saw a man with dreadlocks running out of the woods.

Richardson’s attorneys say he was not aware of Gay’s statement describing someone with a different hairstyle than him when his original defense counsel advised him to take a plea deal. They also say the defense was not informed about a photo lineup police administered to Gay that day, in which she selected a photograph of someone who wasn’t Richardson.

According to a 2021 investigation by the former Virginia Attorney General’s conviction integrity unit, Sussex County Sheriff’s deputy Greg Russell said he showed Gay a single photo of Richardson on the day of Gibson’s murder. Showing a witness a single photo of a suspect is prejudicial and can lead the witness to believe that photo is a photo of the perpetrator.

“I messed that up,” Russell told investigators when interviewed for that review. “This was an improper identification.”

Russell also told investigators that a photo lineup was created later that night in the hopes of creating a proper identification. He said he “was not present for the lineup but believed that [Sussex County Sheriff’s] Investigator [Tommy] Cheek created the photo lineup that was shown to [Gay].”

The Attorney General’s office interviewed Cheek. But Cheek denied any involvement in creating or showing the lineup to Gay.

Confusingly, during the federal case against Richardson and Claiborne, the lead prosecutor said Russell had actually shown Gay a single picture of another man, Leonard Newby.

The prosecutor said that later that evening, Cheek showed Gay a photo lineup containing Newby’s photo among others. Gay’s initials appeared below Newby’s photo.

Richardson was not informed of this before he took a plea deal. Nor was he aware that five days after Gibson’s death, an anonymous caller left a tip on the Virginia State Police’s answering machine, alleging that Newby was involved in the shooting and had since cut his dreads.

“It is clear from the record that some information and evidence presented in Mr. Richardson’s federal trial was unavailable to him when he pled guilty,” former Attorney General Mark Herring wrote in a brief supporting Richardson’s petition for innocence. “It is also clear that no rational factfinder would have found Mr. Richardson guilty had that information been presented in his proceedings in state court.”

More on Terence Richardson

At the May court hearing, Richardson’s attorneys faced stiff resistance from prosecutors as they sought to underscore the importance of these three pieces of evidence. Prosecutors objected to almost every attempt Richardson’s attorneys made to prove their case and even implied that Richardson’s attorneys may have fabricated evidence.

Further complicating the May hearing, more than 25 years have passed since Gibson’s death. As such, many people with firsthand knowledge of the investigation and the events around it either refused to testify, denied being involved, said they didn’t remember, or have since died.

The Sussex County attorney at the time of the murder, David Chappell, testified that he has no recollection of a tip line call identifying another suspect, nor does he recall seeing a photo lineup. Richardson’s previous defense attorney, David Boone, said in court that he relied on his investigator, retired FBI agent Jack Davis, who has since died, to help investigate Richardson’s case.

While Boone said he believed Davis would stop at nothing to investigate a case, he could not say exactly what Davis had done to show diligence during their investigation. From what Boone did or saw directly, he said he was certain the prosecutors had never provided him with the photo lineup, the anonymous call, or evidence pointing to someone other than Richardson.

Gay also testified at the hearing. She said she doesn’t remember speaking to the police, looking at a photo lineup, or even witnessing a shooting. The sheriff’s deputy, sheriff’s investigator, and a state police officer all testified that they didn’t, or couldn’t recall, making or showing the photo lineup to Gay.

Russell testified that he believes Cheek created a photo lineup, but said he didn’t see it or make one himself. Cheek testified that he believes Russell showed the lineup to Gay. A former Virginia State Police officer, Terry Ann Stevens, also said in court that she did not recall showing the photo lineup to Gay, though she confirmed her initials appear on the document because a positive identification was made.

Investigators with the former Attorney General’s office previously raised questions about law enforcement’s handling of Gay’s witness statement and the photo lineup administered to her.

During the conviction integrity unit’s review, they found Gay’s statement to police in the Sussex County Sheriff’s Office’s file and in the Virginia State Police’s file, but not in the county attorney’s record, suggesting police did not turn this information over to prosecutors. Investigators also found a handwritten note describing the anonymous call to the tip line in the case file from the Sussex County Sheriff’s Office—but again, the evidence was not in the county prosecutor’s office, implying police had withheld the evidence.

The photo lineup, meanwhile, did not appear in the case files of the county prosecutor, state police, or county police, according to the investigation by Herring’s office. The lineup was referenced during the federal case against Richardson and Claiborne, indicating that federal agents had a copy of it. Richardson’s counsel said they obtained the lineup through a public records request to federal investigators.

During the May hearing, the confusion surrounding the lineup led to conflicting interpretations by Richardson’s legal team and state prosecutors.

“What is before the Court and on the record is that law enforcement willfully, intentionally, and unconstitutionally withheld documents identifying another witness,” Richardson’s attorney, Sarah Hensley, said during a heated portion of the hearing.

“False,” interrupted Brandon Wrobleski, a prosecutor with Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares’s office.

Wrobleski had previously argued that the photo lineup was not admissible because they could not determine “who wrote these signatures” or when it “was allegedly created.”

“This document is not in evidence, and the Commonwealth objects to foundation, hearsay, and relevance,” said Wrobleski, who threatened to sue the city of Suffolk over its COVID-19 vaccine requirement in 2021.

There is one individual who might be able to clear up the confusion around the lineup: ATF agent Michael Talbert, an architect of the 2001 federal case against Richardson and Claiborne. But Talbert did not testify at the May hearing because the federal government declined to make him available, citing his busy schedule.

Ultimately, Sussex County Circuit Judge William Tomko decided not to allow the photo lineup to be admitted as evidence.

“You’re not going to apparently ever be able to get the federal government to assist you with regards to establishing these documents, but that’s the unfortunate position that you’re in,” said Judge Tomko. “I can’t help that.”

Though Talbert did not testify at the May hearing, he spent an entire day in the courtroom watching proceedings.

“I am not permitted to ask questions of Agent Talbert because the federal government has refused to make him available, though he’s clearly available to testify,” said Hensley.

Richardson’s legal team has maintained that Talbert’s testimony would be crucial to their case, because only he could explain why federal investigators had evidence that Richardson’s initial defense had never seen.

By not participating in the hearing, Talbert avoided testifying under oath or answering any questions defense attorneys may have had for him—but was able to keep a close eye as one of the federal case’s star witnesses, Shawn Wooden, took the stand.

“Mr. Wooden’s testimony changed significantly after his arrest and interactions with Agent Talbert,” Richardson’s attorney, Jarrett Adams, said in court. “He was then given a plea deal to which if he would testify to exactly what he allegedly told Agent Talbert, then he wouldn’t have to serve a day in federal prison. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Adams proceeded to ask the judge to remove Talbert from the hearing over concerns that he was “staring darts at Shawn Wooden and intimidating him from telling the truth.” The judge declined.

After Richardson’s arrest in 1998, he had told police that he was staying at Wooden’s home when the shooting occurred, according to court filings authored by Herring’s office. On the morning of Gibson’s death, Richardson said he woke up around 9:30 a.m., got washed up, then watched cartoons with Wooden’s children.

Gibson was shot around 11 a.m. Richardson said Wooden woke up around that time and that another friend of theirs, Joe Mack, stopped by Wooden’s place around noon. Around 11:30 a.m., Mack’s girlfriend called Wooden’s residence and mentioned that a police officer had been shot, Richardson said. Around 1 p.m., he said he left with Wooden to purchase beer.

Wooden was first interviewed by police in 1998, two weeks after Gibson’s death. At that time, Wooden gave a statement that matched Richardson’s. Asked by police if he suspected anyone of killing Gibson, Wooden said it could be a man named Leonard Newby, because Newby had dreads and a ponytail and cut his hair shortly after Gibson’s death.

But Wooden changed his story shortly after that interrogation. Instead, he said he had gone to purchase drugs with Richardson and Claiborne that morning and acted as a lookout while the two walked through the wooded area behind the Waverly Village Apartments. He said he saw an officer follow them into the woods, then heard a gunshot.

Wooden’s story changed again during the federal case against Richardson and Claiborne. Called as a witness in their trial, Wooden admitted he had lied when he previously told investigators that Richardson and Claiborne were trying to trade something to another person for crack cocaine, according to the conviction integrity review investigation by Herring’s office. More significantly, Wooden said he had actually witnessed a physical confrontation between Gibson, Richardson, and Claiborne, despite previously telling police he had only heard a gunshot and hadn’t been close enough to see what happened.

Wooden was eventually convicted of obstruction of justice for repeatedly changing his statements and sentenced to ten years in prison.

During Richardson’s federal trial, Wooden said that he agreed to testify in the hopes of getting time off his sentence. Additionally, former attorney general Mark Herring noted in his investigation that Wooden said after he cooperated with police, investigators “helped him get a job at a box plant in an effort to get him cleaned up.”

In a court filing requesting that Richardson’s sentence be commuted, Richardson’s defense counsel alleges that Wooden’s friend, Joe Mack, said he had witnessed Sussex police officer Greg Russell give a “white envelope” to Wooden sometime after Richardson’s arrest. When asked about the envelope, Wooden allegedly told Mack he “did what he had to do” to “pay … his rent, light bill, and water bill.”

Judge Tomko issued his findings of fact in June. In the end, the only new evidence he allowed to be admitted was the statement Gay made to police decades ago describing a man with dreadlocks—a hairstyle that differed from Richardson’s at the time.

However, Tomko also ruled that “The document is inadmissible for the truth of any matters asserted. It is admissible solely to show that it was a record of the statement given by Ms. Gay and written down by Detective Russell.” In other words, Richardson’s attorneys can only use Gay’s statement as evidence that police talked to Gay during the investigation.

Next, the Virginia Court of Appeals will request briefs from defense attorneys and prosecutors based on those findings of fact. There may also be another oral argument. But with key pieces of evidence once again suppressed by the law, the odds are stacked against Richardson.

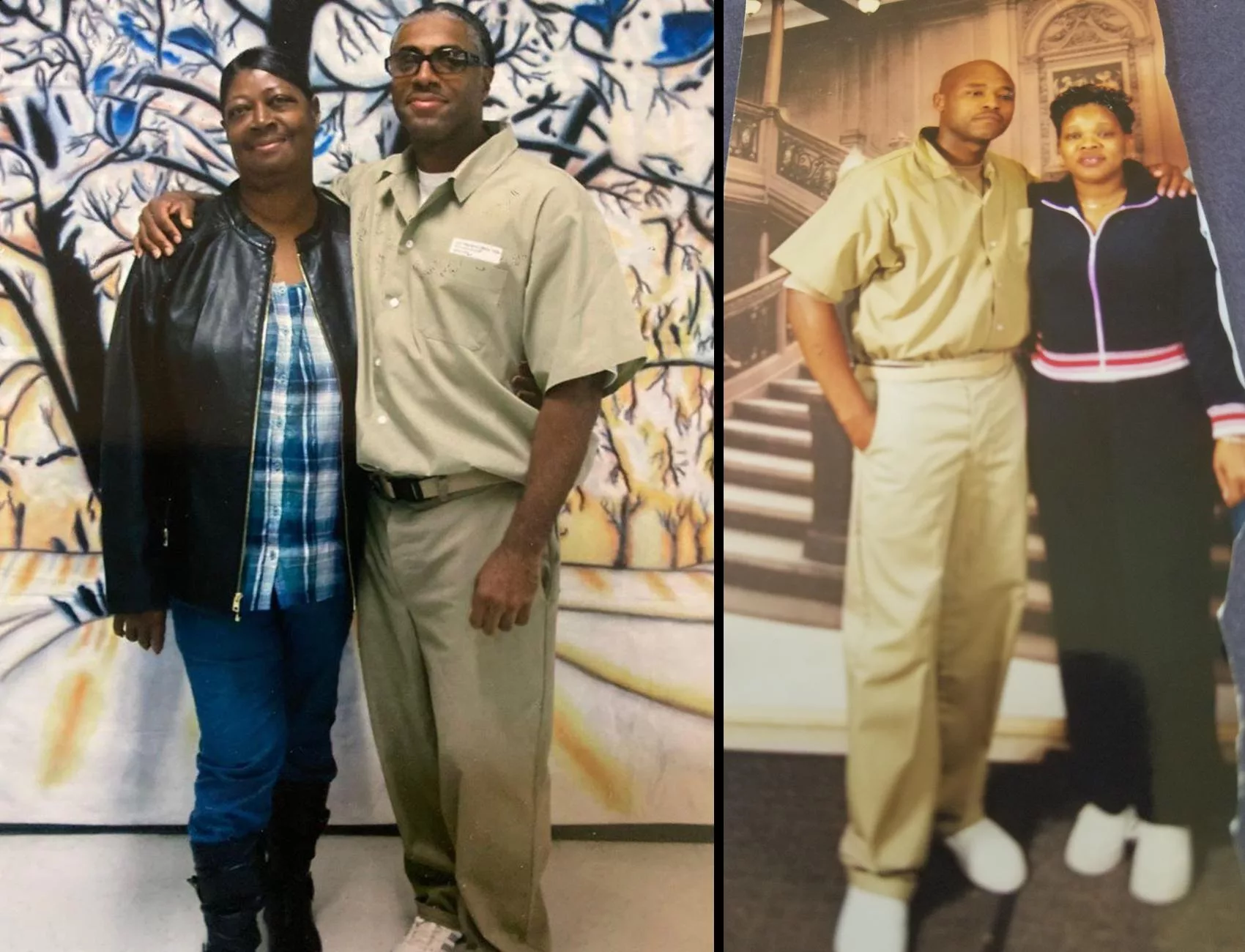

Richardson and Claiborne’s families are still fighting for their freedom. Annie Westbrook, Richardson’s mom, and Brenda Allen, Claiborne’s mom, are calling on President Joe Biden’s administration to grant their sons clemency.

“Terence is an innocent man,” said Adams. “Ferrone is innocent as well. And for whatever reason, there is a clear, orchestrated effort to deny justice.”