Atlanta Voters Want to Decide the Future of Cop City. Will Their Leaders Let Them?

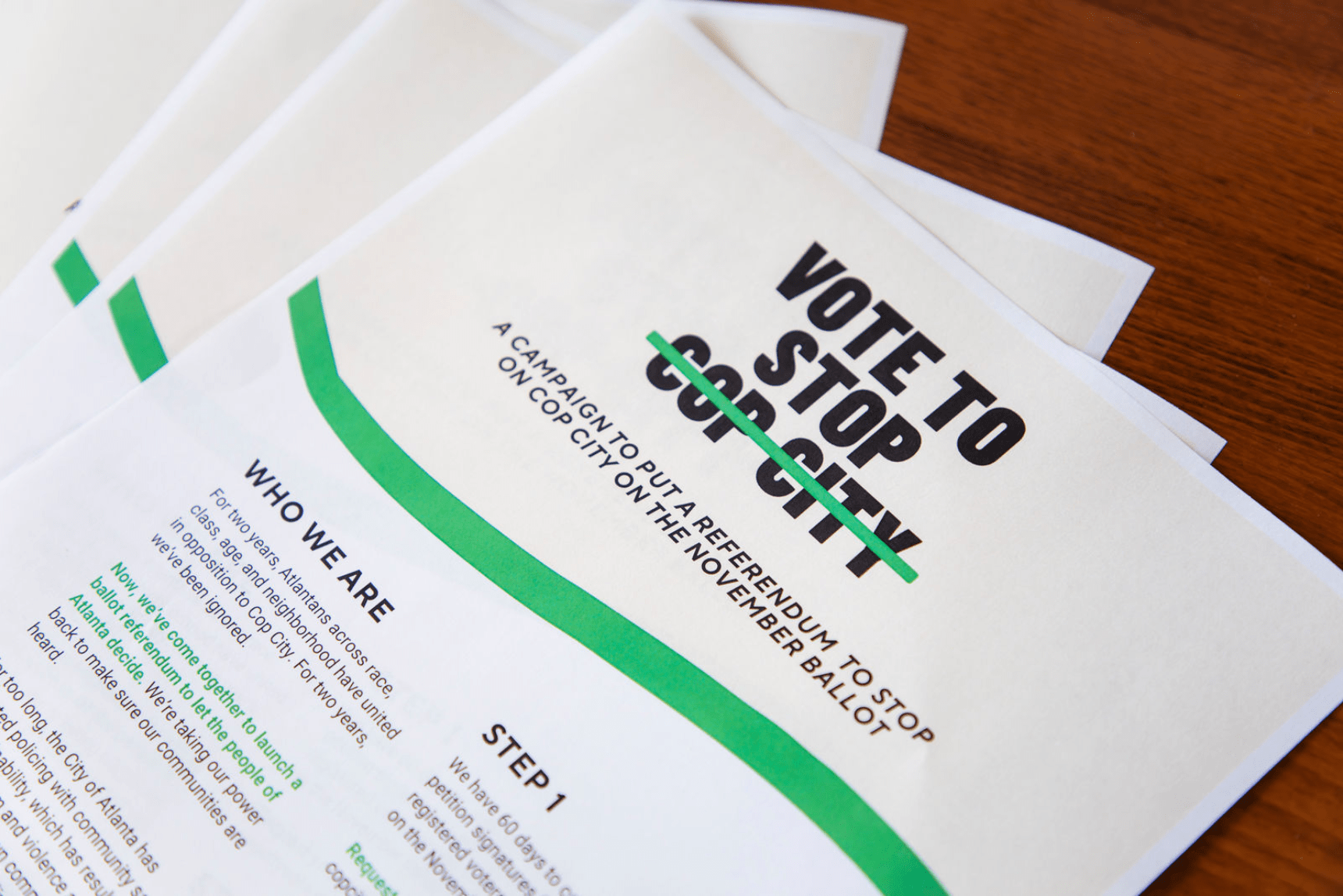

Organizers say they’ve collected thousands of signatures for a referendum to put Cop City on the November ballot. But local officials seem intent on making sure it doesn’t reach a vote.

This story was produced in partnership with The Mainline, an independent magazine based in Atlanta.

Update — July 27, 2:40pm ET: Shortly after publication on Thursday, a federal judge ruled that Atlanta’s residency requirements for petition collectors were unconstitutional. The ruling gives organizers for the referendum to Stop Cop City an additional 60 days to gather signatures and allows volunteers to collect signatures regardless of whether they live within Atlanta. Our original story follows.

Organizers with Atlanta’s “Stop Cop City” movement are in the midst of a referendum effort that would put the fate of the city’s $90 million police training facility up for a vote this November. Supporters have characterized the referendum initiative as an attempt to preserve the democratic process, giving Atlanta residents the final say on whether or not the controversial project should proceed. But with tens of thousands of signatures already gathered, according to the campaign, city and state leaders appear intent on preventing their question from reaching the ballot.

Since organizers announced the referendum in June, city of Atlanta officials have worked to stall the effort and undermine the signature collection process. Lawyers for the city and the state of Georgia have argued the referendum is illegitimate. Some see this opposition as part of a broader, two-year-long trend of anti-democratic interference against the Stop Cop City movement.

“Why is it so difficult to be able to get the city of Atlanta to let residents decide if they want this project?” Jasmine Burnett of Community Movement Builders, a local Black liberation organization that is part of the Vote to Stop Cop City coalition, said in an interview with The Appeal. “Why, in this society that alleges itself to be a democracy, are they, at every turn, shutting down efforts to actually push democratic values?”

Opponents of Cop City launched the referendum campaign just a day after the Atlanta City Council approved a new budget for the complex. The 11-4 vote followed more than 15 hours of public comment, which featured testimony from around 400 residents who overwhelmingly opposed the facility. Critics raised a variety of concerns with the project, with many speaking out about the dangers of an increasingly militarized police force and the environmental harms of plans to raze at least 85 acres of forestland in a low-income, predominantly Black neighborhood of unincorporated DeKalb County.

Despite the community outcry, council members approved a budget significantly higher than previous estimates, raising the price tag of public funding from $30 million to $67 million—with the additional $37 million coming in the form of lease payments to be paid out by the city of Atlanta over the next 30 years. Cop City is a private-public funding project that will be bankrolled by the Atlanta Police Foundation, and corporate donors are providing an additional $60 million in funding. The increased cost to taxpayers, first reported by the Atlanta Community Press Collective in May, has prompted further criticism among residents troubled by the lack of transparency surrounding the project.

Under Atlanta’s referendum process, campaigns have 60 days to collect signatures from at least 15 percent of the city’s registered voters—or around 75,000 people. Petition signers must have been registered to vote in Atlanta in 2021, and a witness who is also an Atlanta resident must be present for the signing.

These requirements impose a relatively steep burden on ballot initiatives in Atlanta. Just under 80,000 people voted in the city’s most recent mayoral election, a runoff in November 2021. For comparison, California requires referendums to collect signatures equivalent to 5 percent of all votes cast in the last gubernatorial election—typically only around 2 or 3 percent of all registered voters.

Organizers in Atlanta have so far gathered over 30,000 petitions, the Vote to Stop Cop City coalition reported on Monday. An initial August 14 deadline for signatures has been extended until late-September in light of Thursday’s court ruling.

Over the past six weeks, the city of Atlanta has used a variety of legal tactics in an attempt to invalidate the referendum effort. When organizers filed in June, a city clerk initially failed to approve the petition within the legally required timeframe. The coalition then filed suit, successfully forcing the clerk’s approval.

In a July 17 court filing, city attorneys claimed the referendum petition was “futile” and “invalid,” arguing the Cop City lease with the Atlanta Police Foundation has already been authorized and cannot be retroactively repealed. Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr has agreed with the city’s interpretation, arguing that the referendum process is only meant to be used to consider amendments to the city charter. Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens has also cast doubt on the legitimacy of the campaign, stating in a July 5 news conference that the effort to collect signatures for the referendum would be “unsuccessful, if it’s done honestly.”

The city’s strategy has been akin to “throwing spaghetti at the wall,” said Paul Glaze, a spokesperson for the Vote to Stop Cop City coalition, in an interview with The Appeal. The resistance from officials shows Atlanta’s leaders are “afraid of democracy,” he added.

Organizers of the Stop Cop City movement say the legal challenges are just one example of the city’s Democratic leadership subverting the will of the people as they work to ram through the proposal.

“I think it’s Democrats taking a page out of Republicans’ handbook,” said Burnett. “The Democrats, particularly in Atlanta and Georgia, like to frame themselves as this progressive alternative to the GOP when they’re really lockstep.”

Some have taken issue with the continued disenfranchisement of DeKalb County residents living closest to the construction site. Although the city of Atlanta owns the land, it is located within unincorporated DeKalb County, which has no representation in the Atlanta city government. As such, DeKalb residents cannot vote on the referendum. Nor can they participate in collecting signatures under Atlanta city law.

“The referendum process in and of itself is still not a reflection of the kind of democratic decision-making and autonomy that our communities deserve,” said Burnett.

Earlier this month, a group of DeKalb County residents filed a federal lawsuit challenging the city of Atlanta’s residency restrictions for gathering signatures.

“The least that could be done to enfranchise us would be to allow us to collect the signatures for the petition,” Reverend Keyanna Jones, a member of the Stop Cop City faith coalition and one of the four DeKalb residents represented in the lawsuit, told The Appeal in an interview.

The judge’s ruling in favor of the plaintiffs on Thursday restarted the 60-day period for collecting signatures, likely pushing the possible Cop City referendum to a March 2024 vote coinciding with Georgia’s presidential primary.

Communities in the Atlanta area have come together in a variety of ways to oppose Cop City since September 2021, when officials first passed the ordinance authorizing the lease agreement with the Atlanta Police Foundation. Authorities have responded with increasingly heavy-handed actions. In January, amid escalating confrontations between law enforcement and protesters camping in the forest near the proposed Cop City site, Georgia state police officers shot and killed 26-year-old climate activist Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán Paez. An official autopsy later revealed that Paez suffered more than 50 bullet wounds during the shooting. An independent examination conducted by Paez’s family determined that Paez was sitting down with hands raised when police opened fire.

Since December, dozens of protesters have also been arrested and charged under Georgia’s sweeping domestic terrorism statute. Legal experts have characterized the prosecutions as politically motivated and unlikely to stick. Others associated with the movement have reportedly faced harassment by police.

The Stop Cop City movement views the ballot initiative as just one possible pathway to halting the facility’s construction, and organizers say they plan to continue their activism even if the effort falls short.

“This movement has been brilliant and creative for more than two years, and we certainly won’t stop now,” Lisa Baker, a volunteer canvasser for the Vote to Stop Cop City coalition, told The Appeal. “I’m confident everyone who has been fighting will continue to fight, and Cop City will never be built.”

Still, for some, the referendum remains an important—if imperfect—tool to fight a broader pattern of voter suppression and disenfranchisement that they say has defined the push to build Cop City.

“When we think about civic engagement and people being involved in direct democracy, how much more direct can you get than a vote on a ballot?” said Jones. “The one thing that the people never got was a vote. The people never had a voice, and our vote is our voice.”