Stop-And-Frisk Made Michael Bloomberg A Big Target In The Presidential Debate. His Opponents Still Missed.

Advocates say the narrowing field of Democratic candidates did not seize an opportunity to lay out clear visions on criminal justice reform to contrast the former New York City mayor’s record on policing.

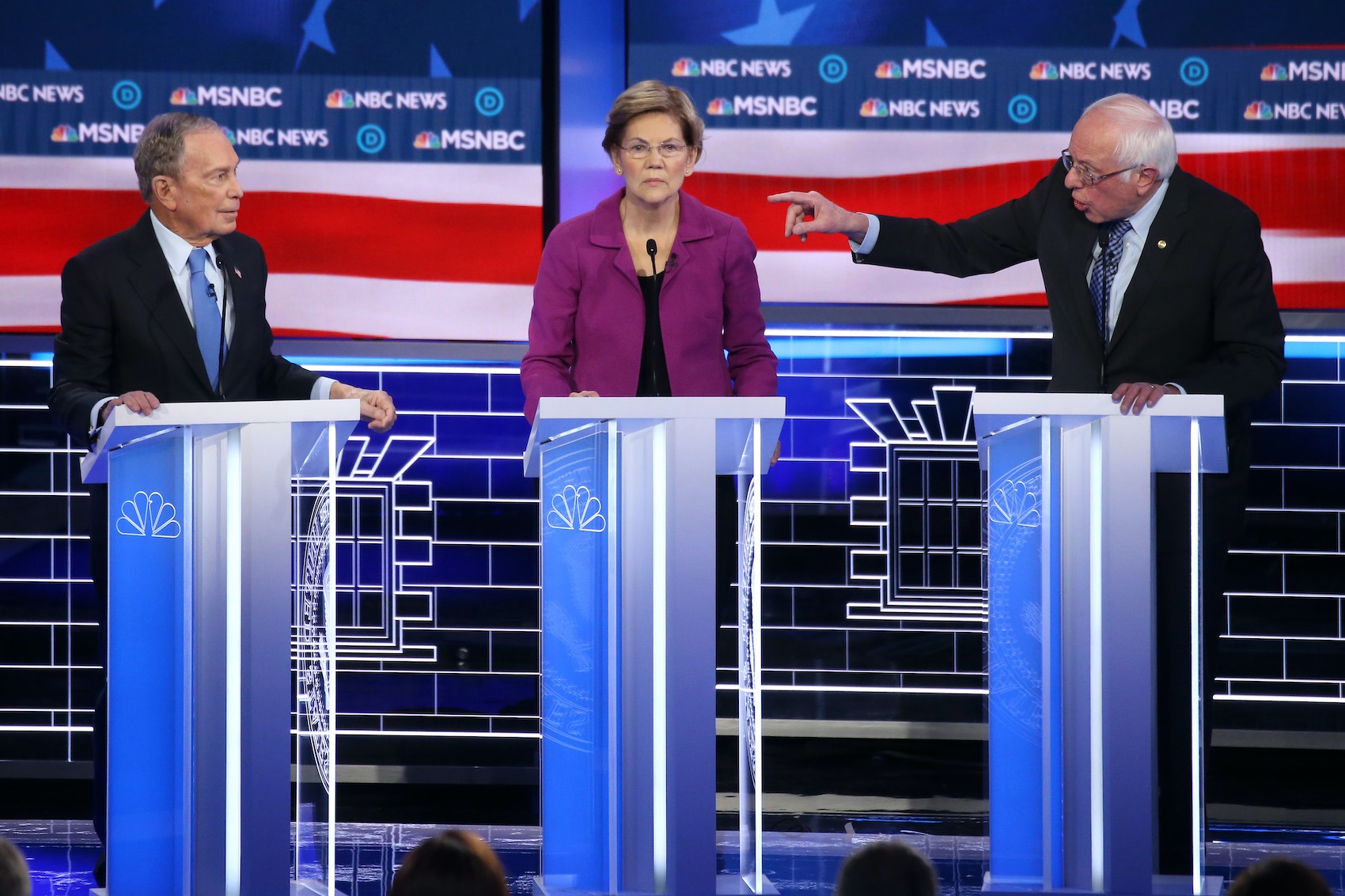

During Wednesday night’s Democratic presidential debate, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg acknowledged again that stop-and-frisk, the controversial policing tactic he endorsed and defended for nearly two decades, was a mistake.

“If I go back and look at my time in office, the one thing I’m really worried about, embarrassed about was how it turned out with stop-and-frisk,” Bloomberg said during the ninth televised debate in Las Vegas, his first since launching his presidential bid in November.

The billionaire former mayor has been skewered by critics in recent weeks over the NYPD’s tactic of routinely stopping, questioning, and frisking mostly Black and Latinx people for weapons. The practice, which predated Bloomberg’s administration and peaked during his 12-year tenure as mayor, resulted in millions of stops. A federal judge ruled it an unconstitutional “policy of indirect racial profiling” in 2013, and the city later installed an independent monitor to ensure the practice was curtailed.

“I’ve sat, I’ve apologized, I’ve asked for forgiveness,” Bloomberg said. “But the bottom line is, we stopped too many people, and we’ve got to make sure we do something about criminal justice in this country.”

If Bloomberg was further distancing himself from stop-and-frisk, he didn’t pivot to proposals that might repair the relationship between law enforcement and overpoliced communities. And none of the five other candidates on stage with him used their allotted time to draw comparison to his plans and their own. It was a missed opportunity all around, criminal justice reform advocates told The Appeal.

“Bloomberg was attacked on issues that were easy to attack him on,” said Howard Henderson, professor of justice administration and founding director of the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University, a historically Black college. “It’s not enough to just criticize him for his policies. They needed to lay out evidence-based solutions that address these harms. That’s the piece that no one on that stage seemed willing to deal with.”

Even if the debates serve as less than ideal venues for meaningful discussions of criminal justice policy, that’s no excuse for not showing leadership on the issue, said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. “It may be hard for a group of white people to communicate the harms of stop-and-frisk, but as a white person who often talks about it, I know it’s just as important to put forth positive programs to address racial inequities that have existed since the foundation of our nation,” she said in phone interview.

Just about every presidential candidate who participated in the debate took shots at Bloomberg over stop-and-frisk. Former Vice President Joe Biden blasted him as insincere in his change of heart because as mayor he initially resisted the installation of federal monitors.

“It’s not whether he apologized, it’s the policy,” Biden said. “The policy was abhorrent, and it was a violation of every right people have.”

“This isn’t about how [stop-and-frisk] turned out,” Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts said. “This is about what it was designed to do to begin with. It targeted communities of color, it targeted Black and brown men from the beginning.”

Although debate topics ranged from healthcare and climate change to immigration and economic policy, some advocates said they anticipated criminal justice reform and policing to dominate more of the discussion, in part because of Bloomberg’s presence on stage. In previous debates, Biden has had to explain his record as the architect of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, federal legislation that critics say exacerbated the mass incarceration of men of color nationwide. Pete Buttigieg, former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, has fielded debate questions about a disparity between Blacks and whites in marijuana possession arrests and police use of force while he led the city. In the eighth debate, and again Wednesday night, Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota was grilled about her handling of the 2003 prosecution of 16-year-old Myon Burrell, which relied on jailhouse informants and discredited experts, when she was the district attorney in Hennepin County.

By comparison, Warren and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont have largely avoided tough questions about their criminal justice bona fides. Although Sanders voted for the 1994 crime bill, reform advocates last August credited him and Warren for having the most decarceral platforms ever in presidential politics.

Erin Haney, senior counsel for the bipartisan criminal justice reform group #cut50, said debate questions about the role of prosecutors, punitive sentencing, police excessive force and prison conditions were unthinkable in presidential politics a decade ago.

“One of the reasons that we’re seeing this on the debate stage at all is because of the decades of tireless work by directly impacted people who pushed this issue into the national spotlight,” she said in a phone interview. “I think we are at a historic moment in terms of criminal justice reform. It’s one of the only bipartisan issues and we can be sure that this is going to be an issue in the general election.”

Bloomberg, who until recently failed to qualify for debates, argued Wednesday night that there is “no great answer” for solving all criminal justice issues. “If we took everybody off this panel that was wrong on criminal justice at some time in their careers, there’d be nobody else up here,” he said.

However, few of his opponents have as glaring a record on policing issues. The number of recorded stops in New York City was highest in 2011 at 685,724—52.9 percent of people stopped were Black, 33.7 percent were Latinx and just 9.3 percent were white. Although Bloomberg has said stop-and-frisk was intended to reduce street violence by searches for weapons, a majority of the stops did not result in confiscation of a firearm, an arrest, or criminal charges.

In November, the former mayor offered an apology to a congregation of mostly Black churchgoers in Brooklyn. “I was wrong and I’m sorry,” he said. But the policy came back to haunt Bloomberg last week, after audio clips of him defending the policy in offensive terms went viral.

As much as Bloomberg and his supporters may want to leave stop-and-frisk in the past, NYPD data released this month shows that it’s still a reality. Police conducted 13,459 stop-and-frisk procedures in 2019, a 22 percent increase from 2018 when officers conducted 11,008 stops. Black and Latinx New Yorkers still made up the majority of those who were stopped last year, according to an analysis by The Legal Aid Society.

“The challenge now [for candidates] is to propose policies that keep that from happening again,” Henderson said.