States Are Enacting Their Own Bans Against ‘Sanctuary City’ Policies

In response, a new ‘Freedom Cities’ movement is rising to defend immigrants’ rights.

Jose “Fito” Salinas is the mayor of La Joya, a tiny Texas city of around 4,000 people less than a mile from the Mexico border. Salinas is 80 years old but still barrel chested, with a good head of hair and a big, silver mustache.

“An old warrior,” he calls himself, adding that “I fear no one.” Still, he worries about a state law called Senate Bill 4.

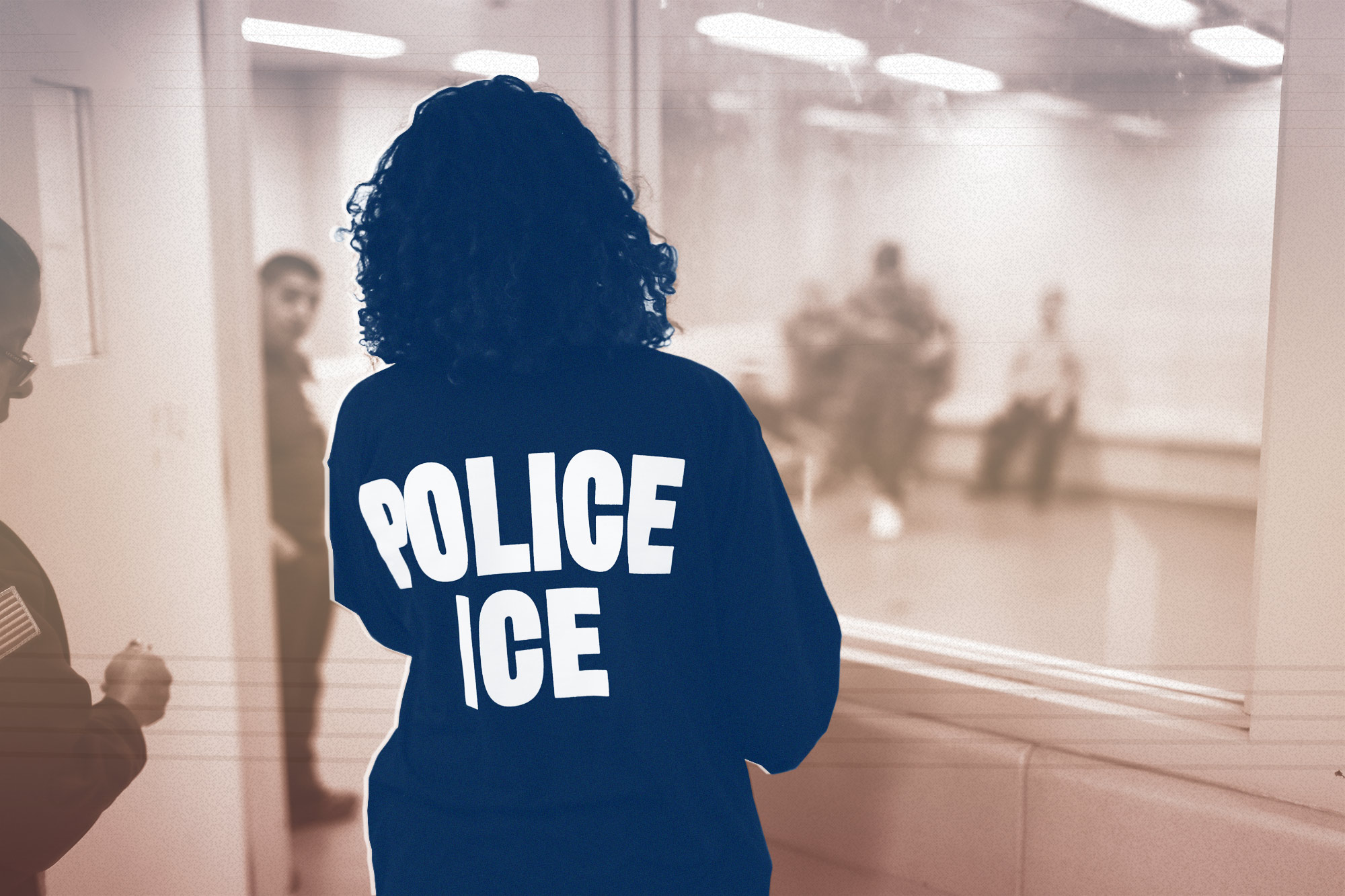

In 2017, the Republican-dominated Texas legislature passed SB4, which allows local law enforcement to inquire about a person’s immigration status. Under the law, police officers can’t be forbidden from asking people whether they are in the U.S. illegally, nor can they be ordered not to share the information with the Border Patrol or ICE.

Since Donald Trump became president, similar anti-sanctuary laws have been enacted in other states, including Iowa, Mississippi and Tennessee.

Still, most states do not have such laws, and many states and municipalities forbid their law enforcement from inquiring about immigration status or sharing such information with ICE.

But in November 2017, the Department of Justice sent letters to municipalities and states, threatening to rescind their funding for criminal justice programs unless they scrapped their sanctuary policies. Ironically, the Trump DOJ cited the Obama DOJ’s argument that under Section 1373 Title 8 of the U.S. Code—known simply as 1373 —local law enforcement cannot be forbidden from sharing information about a person’s immigration status with immigration authorities.

By April, approximately three dozen communities had been warned about their sanctuary policies, including New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New Orleans, as well as counties, smaller cities, and states, including California and Vermont.

Several recipients of the DOJ’s 1373 letters ended up in court. Philadelphia and Chicago sued the agency, and California defended itself after being sued. All argued that 1373 violates the 10th Amendment, which states that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Indeed, several judges recognized that the Constitution says nothing about the states sharing an individual’s immigration status with the feds. So far, two federal courts have declared 1373 unconstitutional. As a result, the law can no longer be enforced in Philadelphia and Chicago. In addition, a court in California ruled that the constitutionality of 1373 is “highly suspect.”

Significant challenges to 1373 also have been mounted in hundreds of cities nationwide. Evanston, Illinois, and co-plaintiff the United States Conference of Mayors, whose membership is open to mayors in the 1,408 cities with at least 30,000 residents, sued the DOJ. Evanston and the mayors group won a preliminary injunction barring 1373’s enforcement. If the injunction is upheld on appeal, 1373 will no longer apply in places as big as Brooklyn and as small as Wenatchee, Washington (population 33,962).

But as of yet, no Conference of Mayors cities have enacted new “sanctuary” ordinances, said Lena Graber, an attorney with the Immigration Legal Resource Center, a San Francisco-based organization that disseminates information about immigration laws and encourages challenges to unjust policies. Graber said that Section 1373 is difficult for many people to understand and city councils often reflexively demur and say “we can’t do this because of 1373.”

Cities have to be “gutsy” to confront the federal law and take on the DOJ, Graber said.

Such gutsiness has come from Texas cities that cannot challenge 1373 because of the anti-sanctuary law SB4. After SB4’s passage, Austin City Council Member Greg Casar, who is Latinx, teamed up with the local community groups Grassroots Leadership, United We Dream Austin, and the Workers Defense Project to craft ordinances to protect immigrants, and people of color in general, against detentions that can lead not only to deportation but jail.

In June, Austin declared itself a “Freedom City,” after council members passed a “cite-and-release resolution” that requires police to cease arresting people for minor crimes such as possession of small quantities of marijuana and instead give them citations.

Austin also passed a resolution stating that if officers stop drivers for traffic violations and ask about immigration status, the people also must be told they have the right not to answer.

Casar shared the Freedom Cities idea with other local officials in Texas, including

Philip Kingston, who serves on the City Council in Dallas. Kingston then spearheaded the passage of a “cite-and-release” policy similar to the one enacted in Austin. It covers a handful of misdemeanors, including low-level marijuana possession. In a few weeks, Kingston told The Appeal, he will ask the Dallas City Council’s Public Safety and Criminal Justice Committee to require that police tell detainees that they do not need to answer questions about their immigration statuses. After that, he will go to the full council. In San Antonio and El Paso, city councils are in the early stages of crafting similar policies.

Freedom Cities, however, have yet to take hold in smaller communities such as La Joya. Before SB4’s passage, Mayor Salinas lambasted Border Patrol agents who entered the town’s ballpark during a 2016 baseball game and arrested a team member’s wife, who was undocumented. He also had his police chief fire an officer after a woman complained that she was asked about her immigration status after she ran a stop sign.

But until The Appeal spoke with Salinas, he had never heard of Freedom Cities. He mulled the concept briefly but then returned to his anxieties about SB4. He wondered whether he could get fined or arrested if he objected to one of his police officers asking a driver an immigration question, or calling the Border Patrol.

It was not a happy thought for the mayor. It was about cities but not about freedom.