Spotlight: Neighborhood Crime Apps Stoke Fears, Reinforce Racist Stereotypes, And Don’t Prevent Crime

If I open an app called Citizen, which offers neighborhood “911 crime and safety alerts,” an alert pops up: “200 FEET AWAY: police search for four suspects after shooting incident.” There is a thumbnail picture of a map with a bright red dot in the middle, and shades of red cover the area around […]

If I open an app called Citizen, which offers neighborhood “911 crime and safety alerts,” an alert pops up: “200 FEET AWAY: police search for four suspects after shooting incident.” There is a thumbnail picture of a map with a bright red dot in the middle, and shades of red cover the area around the dot, as if half of Brooklyn is currently under a red cloud of danger.

Yikes. But underneath is another message:

We can’t verify your location: Citizen can’t send you urgent nearby crime and safety alerts unless you set your location services to “always allow.”

So, no shooting. Just a naked attempt to scare me into giving my location data. But it only made me laugh at the idea that an app could try to shock me with news of a shooting on my block and also admit it didn’t know where I was. Besides, I know my neighborhood. I walk around. I’m friends with my neighbors. I am part of an email group for the block and a social media group for the neighborhood, where I learn about lost pets, block parties, notorious landlords, and bikes for sale. If a shooting happened 200 feet away from me, I think I would know.

Violent crime in the U.S. is at its lowest rate in decades. But you wouldn’t know it if you use one of the increasingly popular social media apps that stoke fears of crime to gain a user base. “Apps like Nextdoor, Citizen, and Amazon Ring’s Neighbors—all of which allow users to view local crime in real time and discuss it with people nearby—are some of the most downloaded social and news apps in the U.S.,” writes Rani Molla for Vox. Nextdoor has become a “hotbed for racial stereotyping.” Citizen, which sends users nearby 911 alerts, was originally called Vigilante, and encouraged users to fight crime on their own. A highly produced video ad for the app—in which a woman is being pursued by a man in a “dark hoodie” under a bridge—seemed to be recruiting potential George Zimmermans. Citizen also allows users to livestream footage, chat with other users, and create a personal safety network, to receive alerts whenever anyone is “close to danger.”

“In the alternative reality that is Nextdoor, people are committing crimes I’ve never even thought of: casing, lurking, knocking on doors at 11:45 p.m., coating mailbox flaps with glue, ‘asking people for jumper cables but not actually having a car,’ lightbulb-stealing, taking photos of homes, being an ‘unstable female’ and ‘stashing a car in my private garage,’” writes Joel Stein for the Chicago Tribune. “Last time I looked at Nextdoor, it attempted to scare me with ‘Black Audi no license plates scoping the hood again.’ My neighbors can somehow make an Audi seem frightening.”

Amazon’s Ring, a doorbell equipped with a video camera, and Neighbors, the accompanying social media app, recently advertised an editorial position that would coordinate news coverage on crime. Neighbors describes itself as “the power of your community coming together to keep you safe and informed.” It alerts users to local crime news from “unconfirmed sources” including Amazon Ring videos of people taking Amazon packages and “suspicious” brown people on porches.

“These apps have become popular because of—and have aggravated—the false sense that danger is on the rise,” writes Molla. “Americans seem to think crime is getting worse, according to data from both Gallup and Pew Research Center. In fact, crime has fallen steeply in the last 25 years.” Unjustified fears and racist neighborhood watches are not new. But the proliferation of smart homes, social media alerts, and doorbell cameras have scaled it up, fomenting fear around crime, and reinforcing stereotypes around skin color.

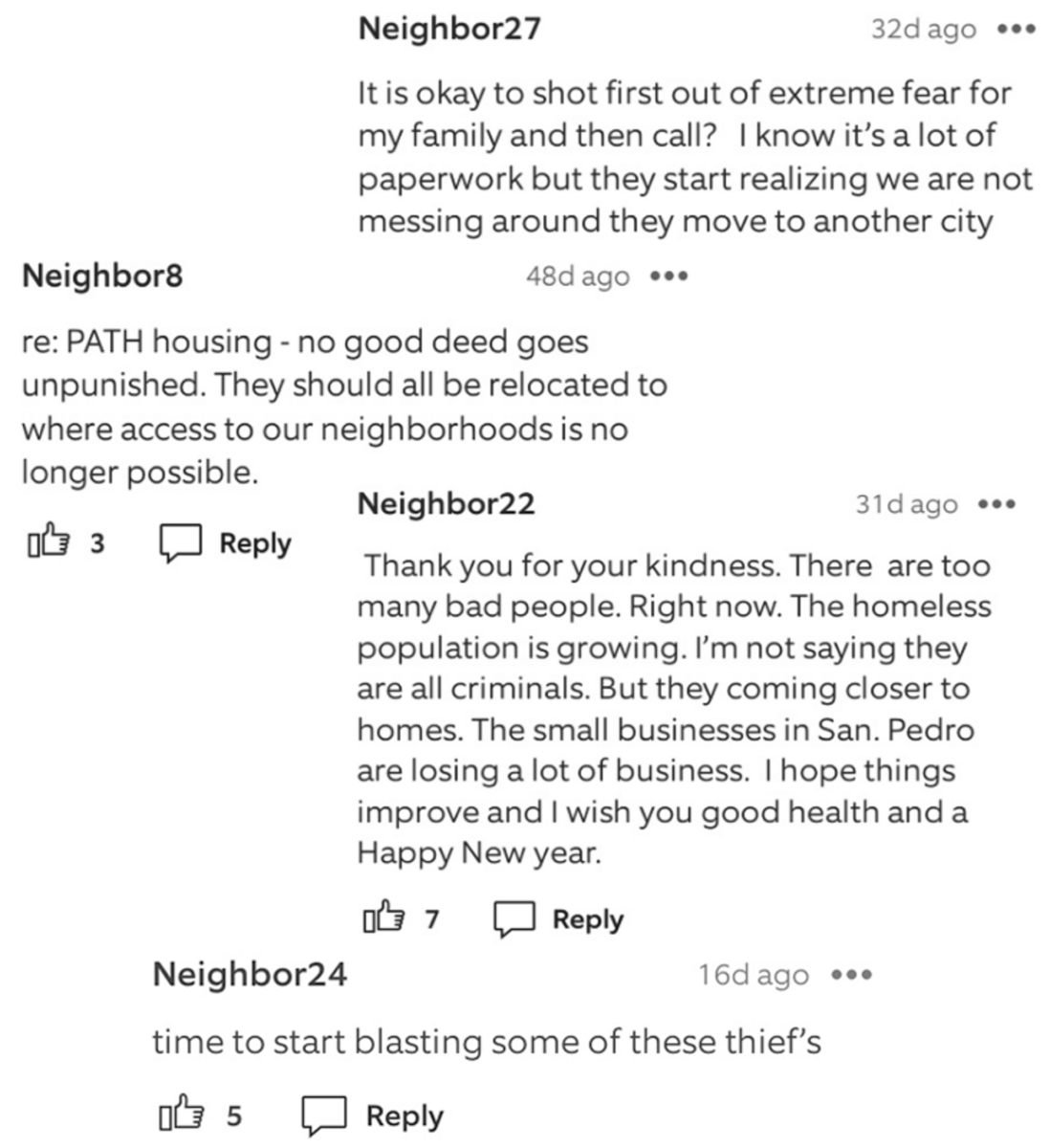

As Steven Renderos of the Center for Media Justice, said, “These apps are not the definitive guides to crime in a neighborhood—it is merely a reflection of people’s own bias, which criminalizes people of color, the unhoused, and other marginalized communities.” The apps “can lead to actual contact between people of color and the police, leading to arrests, incarceration and other violent interactions,” including police shootings. And as police departments shift toward “data-driven policing” programs, he said, the data generated from these interactions becomes part of the crime data used by predictive policing algorithms. “So the biases baked in to the decisions around who is suspicious and who is arrested for a crime ends up informing future policing priorities and continuing the cycle of discrimination.”

For all of the downsides, William Antonelli points out in The Outline, there’s no proof that these programs reduce crime—the only one that claims it does is Ring, and it refused to supply the MIT Technology Review with any specific evidence. “Some independent studies reported to the Tech Review actually showed that houses with Ring cameras are broken into more. But that hasn’t stopped police departments across the country from giving Ring cameras out to citizens and monitoring the posts for potential crimes.”

Ring recently partnered with various local law enforcement agencies in Georgia, Florida, Texas, and California, allowing officers to monitor security video, and any other video, posted on the app. Just as Axon, maker of the Taser stun gun, equipped police forces with body cameras for free to expand its user base, Amazon is “donating” its video doorbells to communities with police partnerships, and police often install them on people’s doors. “Police regularly use videos recorded by Ring devices and other kinds of surveillance cameras to identify suspects or ask for the public’s help in identifying them,” according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “This new network will allow residents to submit these kinds of videos even if a crime has not occurred, in case of suspicious activity or other out-of-the-ordinary occurrences residents may consider potentially helpful to police.”

All of this sounds terrifying, and perhaps this kind of crowdsourcing will not subside until local journalism picks up across the country, but there is precedent for fearmongering apps being driven out of existence for being too racist. Four years ago, a writer—who happens to be married to this writer—chronicled the short life of SketchFactor, an app that “would allow users to report having seen or experienced something ‘sketchy’ in a particular location.” Serious pushback came before the app was even launched, including a Gawker headline that read “Smiling Young White People Make App for Avoiding Black Neighborhoods,” and a tweet from the writer Jamelle Bouie: “Are you afraid of black people? Latinos? The poors? Then this app is just for you!” SketchFactor’s Twitter feed was inundated with such hashtags as #racist, #classist, and #gentrification. The young (white) entrepreneurs behind the app never officially admitted defeat, but eventually they “pivoted.”

This Spotlight originally appeared in The Daily Appeal newsletter. Subscribe here.