Spotlight: Marion Wilson’s Execution Is a Grim Milestone

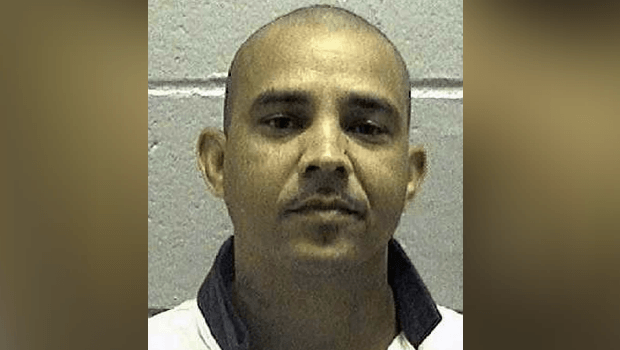

Marion Wilson’s was the 1,500th execution since 1976, the year Georgia resumed the death penalty after the Supreme Court’s decision in Gregg v. Georgia.

Marion Wilson was killed by the State of Georgia last night. His last words were, “I never took a life.” It was the 1,500th execution since 1976, the year they resumed after the Supreme Court’s decision in Gregg v. Georgia.

In The Intercept yesterday, Liliana Segura reflected on Wilson’s execution, and the state of capital punishment in Georgia and nationwide. Regarding Georgia, she wrote, “With some 50 people on death row—and having carried out 73 executions since Gregg—Georgia is neither the largest nor the most active death penalty state in the country. But it has consistently exposed the ugliest truths about who we condemn to die.” In 2015 alone, the state executed “a Vietnam veteran with severe PTSD, a man diagnosed with an IQ of 70, a woman who became a theologian and mentor to scores of incarcerated women, and a man who credibly insisted until his last breath that he was innocent.”

On Twitter, Sister Helen Prejean pointed to some of the many “irreparable flaws” in the death penalty system that manifested themselves in Wilson’s case and made his execution possible. Among them: The prosecutor who tried Wilson said during the trial that he did not know whether it was Wilson or his co-defendant who had pulled the trigger in the shooting of Donovan Parks. Yet at Wilson’s sentencing, he insisted to the jury that it had been Wilson. Years later, the prosecutor admitted under oath that he believed it was Wilson’s co-defendant, Robert Butts, who had killed Parks. Both Wilson and Butts were sentenced to death and Butts was executed last year.

Nationally, Segura describes a death penalty landscape “filled with … contradictions.” Depending on which trends one looks at, it can seem on the verge of extinction or resolutely in place. Death sentences and executions are in decline. There were 60 executions in 2005 and only 25 last year. Nine states have ended capital punishment, through legislation or court rulings, including New Hampshire just this year, and four have moratoriums in place. Yet in some states, executions “are surging.” Tennessee even brought back the electric chair last year, after no executions for years. And in the White House, President Trump calls for executions for drug dealers.

As the race for the Democratic nomination for president is well underway, the candidates have been largely united in opposing the death penalty. In a set of interviews published by the New York Times this week, 20 of 21 candidates, several former prosecutors among them, expressed opposition. The only exception was Montana Governor Steve Bullock, who said he would reserve its use for the most “extreme circumstances, like terrorism.”

Joe Biden did not participate in the interview but even his longtime support for the death penalty may be under strain, at least in public pronouncements. The 1994 crime bill he authored created 60 new death penalty offenses under 41 federal capital statutes and, as Vox’s German Lopez pointed out in an analysis of the crime bill published yesterday, Biden “bragged” immediately after its passage that “the liberal wing of the Democratic Party” was now for “60 new death penalties,” “70 enhanced penalties,” “100,000 cops,” and “125,000 new state prison cells.” Yet this month, in New Hampshire, Biden congratulated the state on passing a law that abolished the death penalty, leading to speculation that he could reverse his position on the issue.

But opposition at the federal level, which accounts for 62 people on death row, compared to over 2,700 in state prisons, can only go so far in ending the death penalty. A look at two counties that are among the country’s largest contributors to death sentences is a reminder of how capital punishment at the local level, while at “generational lows”, is still stubborn.

In California, Governor Gavin Newsom announced a moratorium on executions in March. But this week, the ACLU released a report on death sentences out of Los Angeles County under District Attorney Jackie Lacey. The report looked at the 22 death sentences that have been handed down during Lacey’s tenure, since 2012. In contrast, Harris County, Texas, which once contended for the title of death penalty capital of the country, has had six death sentences imposed since 2013. Yet 59 percent of LA County residents oppose capital punishment, according to a 2019 poll.

Those 22 death sentences represent a toxic brew of what Cassandra Stubbs of the ACLU described as “abysmal defense lawyering, geographic disparities, and racial bias” that “are the legacy of [LA County’s] unfair and discriminatory use of the death penalty.” Of the 22 people sentenced to death in Los Angeles, not one was white. Though only 12 percent of homicide victims in the county between 2000 and 2015 were white, 36 percent of those sentenced to death were convicted of killing at least one white victim, according to the report. Eight of the defendants were represented by lawyers who have been charged with misconduct.

In The Appeal today, Joshua Vaughn talks about Caddo Parish, Louisiana, where James Stewart succeeded District Attorney Charles Scott in 2015 after Scott’s death that year. As Vaughn writes, between 2010 and 2014, Scott, along with two of his assistants, was “principally responsible for making Caddo Parish, Louisiana, the death penalty capital of America.” Between 2006 and 2015, its rate of death sentences for homicides was eight times higher than the rest of Louisiana.

When Stewart ran for DA, it was unclear whether he would be a reformer, but he did run on a message of change. However, his handling of death penalty cases brought during Scott’s tenure has worried observers. In one case, where the jury deliberated for less than two hours before returning a death sentence, Stewart’s office has fought post-conviction motions to compel discovery, and has issued redacted documents to the defense. Prosecutors even went so far as to request financial compensation from defense attorneys for their time.

The attorney in that case told The Appeal in an email, “DA Stewart should look closely at the death sentences sought and secured by [assistant DA] Dale Cox, rather than defend them with Cox’s vigor.” He also said, “James Stewart was elected District Attorney because Caddo Parish voters rejected Dale Cox’s ‘we should kill more people’ view of justice.”

This Spotlight originally appeared in The Daily Appeal newsletter. Subscribe here.